Love letters have always occupied an important place in the history of mankind. On Valentine’s Day, Qalam shares love notes across the epochs, ranging from ancient Novgorod all the way to the Ottoman Empire.

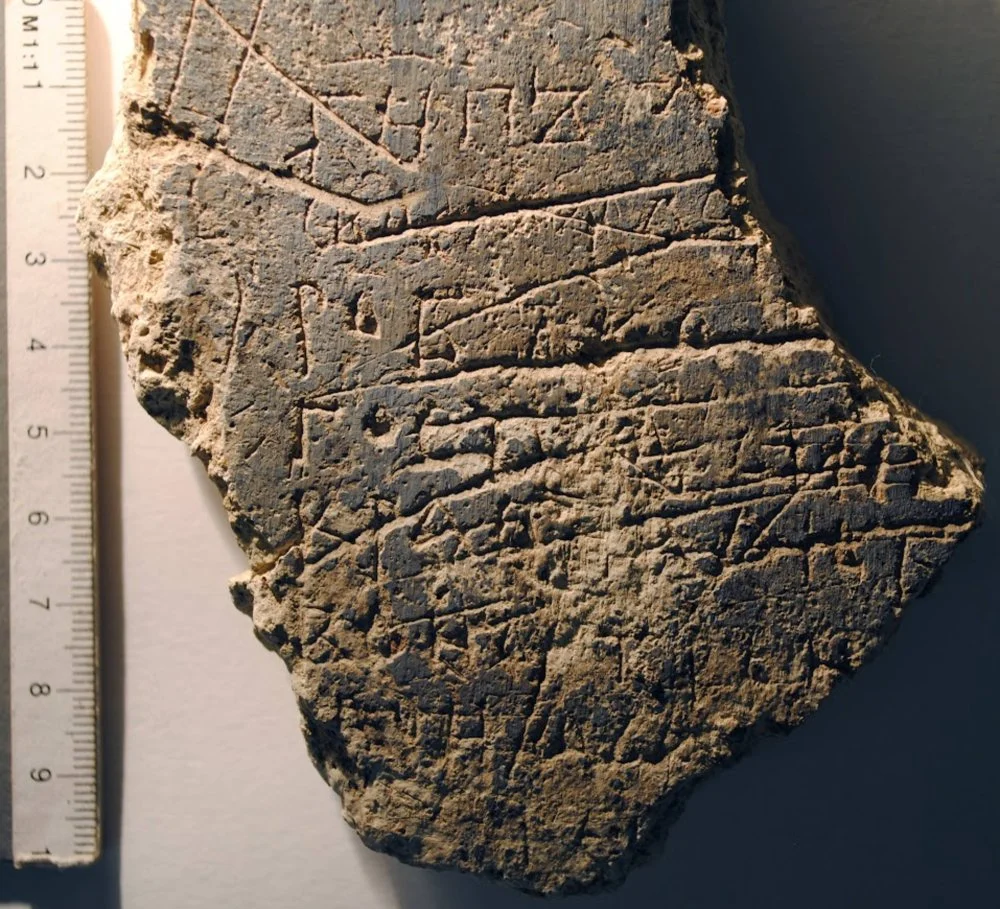

Love Notes Scratched on Birch Bark (Twelfth to Thirteenth Centuries)

Medieval Novgorod left the world a most unique gift: insights into what the real lives of people from that era were like. Today, more than 1,000 letters, shedding light on the personal experiences of its inhabitants, have been unearthed, among them love letters.

1. Thrice did I send for you. Why do you have such anger toward me that you were unable to even pay me a visit? You are to me like a brother. Could it be that my sending for you upset you? You, it appears, have no such interest in me. For if you did, you would have quietly set off to see me. Now you are in a new place. I demand that you write without further delay—do you want me to forget about you? Even if my foolishness has managed to offend you, do not play with my feelings, for God and my sorrow will be your judge. (Beginning of the twelfth century)

2. From Nikita to Anna. Be my wife. I want to be with you, as you do with me. Ignat has agreed to be my best man. (End of thirteenth century)

Birch bark love letter. Velikiy Novgorod, 1100-1120/gramoty.ru

A ‘Valentine’ from a Fifteenth-Century English Prison

A French prisoner, the Duke of Orleans, having found himself incarcerated in the Tower of London after the Battle of Agincourt of 1415, wrote this note to his wife:

I am already sick of love, my very gentle Valentine.i

The Duke of Orleans sitting in the Tower and writing a letter to his beloved. English miniature. Early 16th century/British Library

Girlfriends Discussing a Groom (Eleventh to Twelfth Centuries)

On the walls of the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, graffiti from centuries past remains meticulously preserved. Among them is a mysterious note, but one clearly dedicated to love:

‘A goat consults with a demon whether she should marry a ram.’

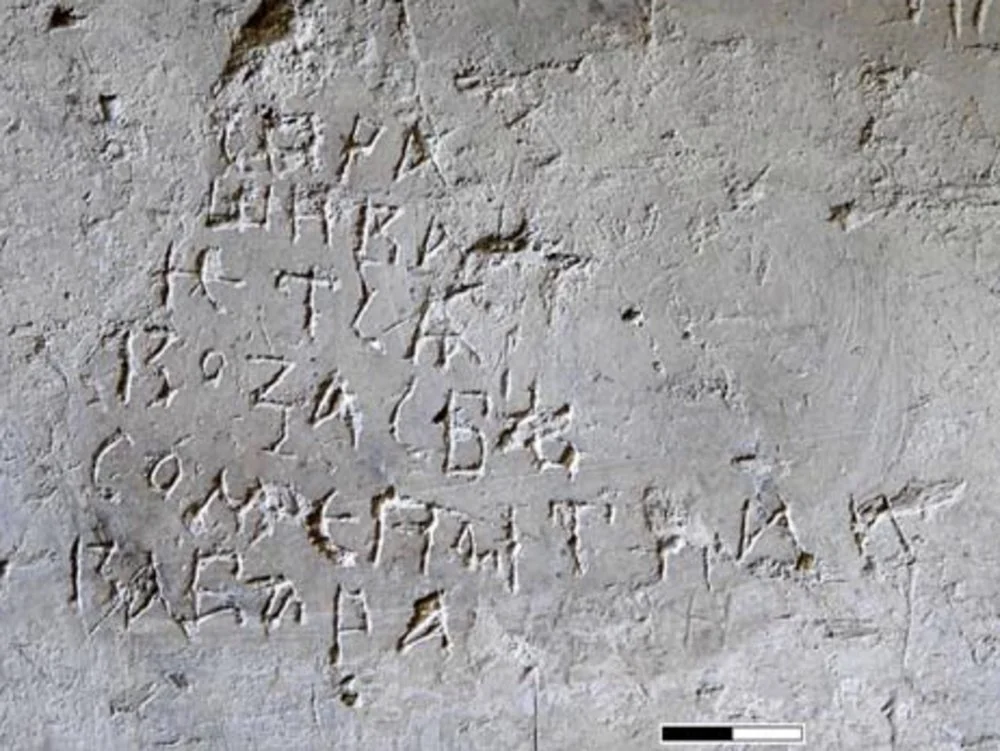

The inscription on the matchmaking of a goat and a ram with the participation of a demon, the Walls of the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv 1280-1320/epigraphica.ru

Dreaming of a Mistress (Twelfth Century)

In another Sofia, this time in Novgorod, parishioners also wrote about love. For example, a young man hopes that a beauty from Novgorod also shares his feelings.

‘She is so timid, so beautiful—I feel love originating in my gut…’

Fragments of fresco plaster. A record of love for the "timid mistress". The Cathedral of St. Sofia, Velikiy Novgorod, Russia. 1144/epigraphica.ru

Letters from a Harem (Sixteenth Century)

Roxelana, also known as Hürrem, was a femme fatale, famous for seducing the great Sultan Suleiman. But how could anyone resist such words?

‘Please accept the pitiful agony of your hopeless servant, immersed in melancholy from the ache of my yearning for you … Should the winds bring my pain to you, then you will know the lament of your servant, moaning like a nightingale. I am sending you clothes drenched in my tears. Wear them and remember me.

I am the one who is lost in this place, the Almighty’s universe. I have lived the spring of my life under your protection, like a pearl in your box of jewels. Please accept the wretched agony of your despairing servant, who is engulfed in sorry because of the pain and torment of such a hopeless longing. Only in your presence can I find peace.

If the winds should carry my anguish to you, then you will understand that my lament is like a nightingale’s mournful song. When I am parted from you, I can find no solace as my strength wanes, with no remedy in sight. No one can ease my pain. If you could see my soul, filled with such deep sorrow, you would immediately understand that I am now sick and broken, like a reed flute howling from the suffering of separation.

—Your poor and despicable concubine.’

Anton Hickel. Roxelana and the Sultan. 1780/Wikimedia Commons

Love from the Mouth of a Volcano (First Century CE)

Pompei is famous not only for having been buried under volcanic lava and ash but also because of extensive inscriptions left on the walls by its inhabitants. And what did they write about? Politics. Love. And sometimes unrequited love.

‘Why do you delay our happiness, while fanning my hope by always saying “Perhaps tomorrow?” If that is the case, and you force me to live without you, then let me die now. Bringing an end to my misery will be your gift to me.’

‘Marcellus loves Praenestina, but she could care less about him.’

‘Floronius, a privileged soldier from the Seventh Legion, was here, but women were unable to know him as a man, except for a select few, of which there were six.’

View of Pompeii. 1864 / Alamy

A Broken Heart in Ancient Egypt (Second Century CE)

This is a rare testament to the fact that Egyptians were concerned about more than just the afterlife.

‘I, Seren, offer my greetings to my sister, Lady Isidora. First, I pray for your health and every day and evening I offer my worship to the goddess Tauret, who loves you, in your name. I want you to know that since you left me, I have been in mourning, crying all night and grieving all day.

From the day that you and I last washed ourselves together, the twelfth day of the month of Farofa, I have not washed or anointed myself with oil, and will not do so until the twelfth day of the month of Atir.

You sent me letters that could have moved a stone, so heavy were the words. In the same hour, I responded to you and gave it to you on the twelfth, sealed along with your letters.

In addition to your letters, in which you write: “Kolob has made a prostitute of me,” the messenger said these words in words: “Your wife sent me to tell you that you, yourself, sold the chain and that you put her on the ship yourself.” Are you sharing this information all around so that people will no longer believe me about your boarding the ship on your own? Look how many times I have sent for you. Let me know whether you are coming or not.’

On the back of the envelope is written: ‘Give this letter to Isidora, from Seren.’

Ancient Egyptian married couple. c. 2400 B.C./Wikimedia Commons

Coded Love

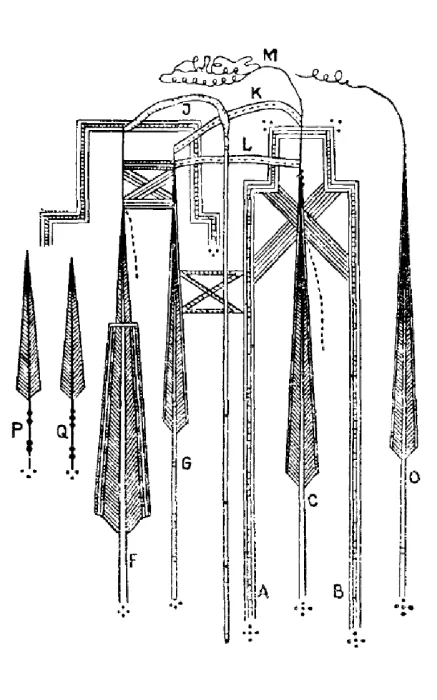

The Yukaghir people of Northern Siberia, a population that is slowly dying away, wrote unusual letters—ideographic ones. Several such letters were preserved by ethnographers of the early twentieth century.

Gustav Kramer, "Globe" magazine. Yukaghir love letter. 1896/from open access

The letter here is believed to be the transcript of a love letter from a girl:

‘You have moved far away and live there with someone else, you two have children, but I still can’t forget you and am filled with sorrow. Our love has been torn apart, but I still can’t accept a man who repels me.’

As you can see, love knows no bounds, and you can write about it in different ways and, most importantly, using different formats.