At the dawn of the twentieth century, the Kazakh steppe was undergoing a series of rapid transformations. Foreign merchants, engineers, and adventurers—especially from Britain—arrived expecting wilderness, only to find booming butter exports, thriving mines, and busy trade offices. For many, it was a revelation: the steppe was not an empty frontier but a landscape pulsing with modern enterprise and cross-cultural exchange. Their first-hand accounts reveal not only industrial growth and imperial rivalries, but also vivid encounters with nomadic life on the eve of revolution. And through their eyes, Nick Fielding takes us into a world where steam engines met horse caravans, and the old rhythms of the steppe danced with the forces of modernity.

A Commissioner’s Surprise

On 25 May 1903, Henry Cooke, a special trade commissioner from the British Commercial Intelligence Committee, set off from Moscow on a journey, scheduled to last six months, through some of the most remote parts of the Russian Empire lying to the east of the Ural to investigate the prospects for British trade in Siberia. He was undoubtedly surprised by what he found, especially in what was then called ‘Western Siberia’ and is what is mostly part of Kazakhstan today.

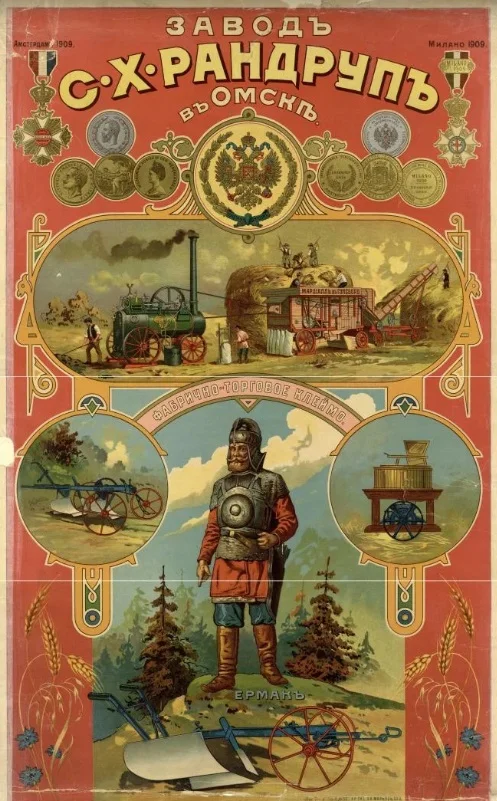

Advertisement for a plow factory in Omsk. The factory belonged to the Danish entrepreneur S. Randrup. 1909 / Wikimedia Commons

It seems strange to discover that the Germans, French, Americans, Danes, and English were already well ensconced in trade in the area, particularly in Akmolinsk Oblast and in the Tomsk Governorate, which included large parts of what is now north-eastern Kazakhstan.

Cooke wrote in his official reporti

Even now Russian immigrants into Siberia, peasants though they be, are supplying the London market with butter, and as they reap their crops with American harvesters, they discuss with intelligence the rival preferences of machines from Milwaukee or Chicago.

When we think of these regions before the First World War, we seldom consider the inroads made by foreign businesses, especially in agriculture and mining. At this point, only a few decades had passed since the old Central Asian khanates had been suppressed by the military might of the Russian Empire, and there was no local tradition of industrial manufacturing. To outsiders, much of the area would have seemed like a vast and empty wilderness. And although the Trans-Siberian railroad had been completed by 1895, it was not until 1931 that the Turkestan–Siberian Railway, more commonly known as the Turk–Sib line, stretching from Tashkent, via Bishkek and Almaty, before heading north to Semey and then on to Barnaul and Novosibirsk, was completed. Nonetheless, in at least two areas—butter production and mining—business was booming.

The Butter Boom on the Steppe

Surprising as it may seem, Cooke spent some time investigating the production of butter in the rich grasslands along the banks of the Irtysh River, where he saw plenty of evidence of European goods being sold. The Germans were active everywhere, the French were selling fancy goods, the Belgians were selling guns, and the Austrians scythes and sickles. But it was the Danish industrialization of butter production and American provision of agricultural equipment that really made an impact on him. Britain, even at this time, was the main purchaser of local butter, buying exports that brought Russia an annual income of 25–30 million roubles. This steady profit, in turn, allowed farmers to invest in American-made hay mowers and rakes, helping them modernize their farms and improve agricultural efficiency.

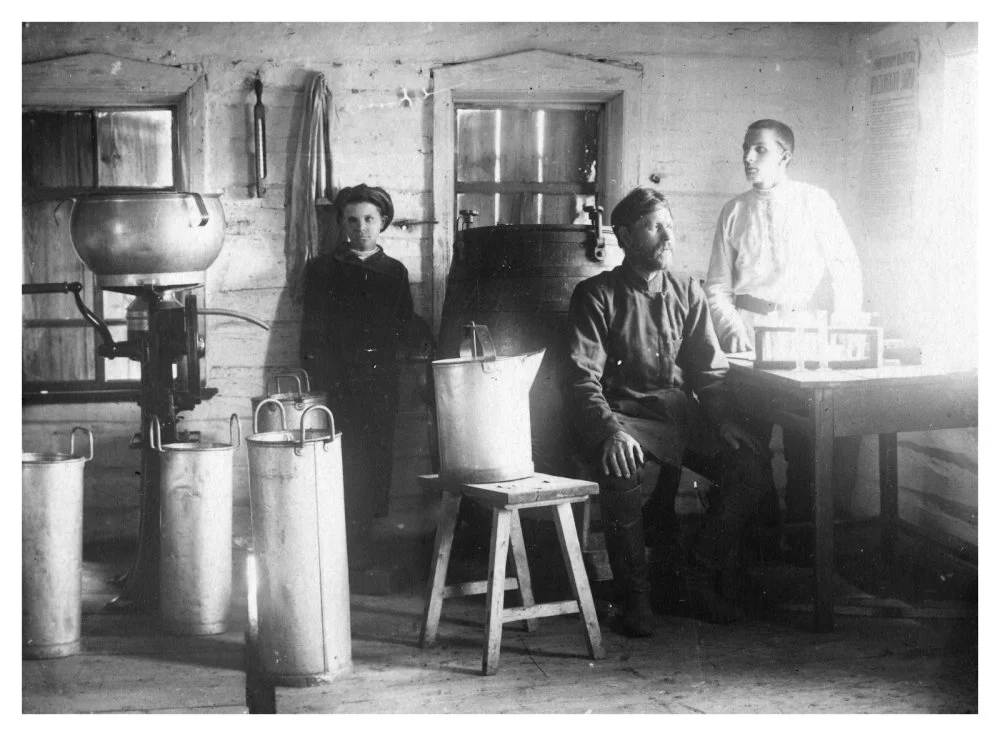

Butter-making plant in Altai (Abatskaya Volost). Early 20th century / https://safe-rgs.ru

These southern steppe regions, particularly in Akmolinsk and in the foothills of the Altai Mountains, had only recently been settled by tens of thousands of Russian migrants who had been offered cash inducements to establish new farms and introduce both crop cultivation and cattle breeding to the area. In 1900, the total population of Siberia was roughly 7.8 million, more than double what it had been 40 years previously. Three-quarters of these people were Russians, with around a million Kazakhs, 250,000 Buriats, and similar numbers of Tatars and Yakuts. Most of the Russians, however, were recent arrivals.

Resettlement farmstead in the Nadezhdinsky settlement with a group of peasants. Near Petropavlovsk. 1911/Wikimedia Commons

Russian immigration to Siberia grew rapidly during the 1890s as state lands totalling 9.4 million hectares were transformed into agricultural plots for migrants. The development of the railways was the main reason that industry began to develop in Western Siberia. Instead of using the immense waterways—which were always frozen in winter—goods trains now transported agricultural produce and minerals back to Russia and onwards to the European markets.

Butter production depended on Kazakh cattle, particularly on a small breed developed by Kazakh farmers over generations and able to withstand the harsh steppe winters. As Cooke noted,

In spite of primitive keep, Siberian cattle stand the climate well. The cows, if not as productive as they might be, yield an exceedingly rich milk.

Sheep farming also played a part in the steppe economy, with imported merino breeds from Crimea adapting to the new conditions very well. By 1902, wool exports from western Siberia had reached 4,000 tonnes, another indicator of the region’s growing agricultural prosperity.

S. Dudin. Shepherd. 1899 /Wikimedia Commons

Cooke notes that prior to 1893, no butter was produced in Siberia for export. In 1886, an Englishwoman in the Tyumen district, who was married to a Russian, began to produce butter using modern methods. She bought a Swedish separator the following year and business boomed. In 1893, a Russian businessman in Kurgan opened the first dairy exporting butter, and in his first year, he was able to export about six tonnes. Incredibly, within ten years, butter production had become the main industry for this whole region of Siberia. By 1903, exports had reached 35,000 tonnes from more than 2,000 mostly cooperative dairies.

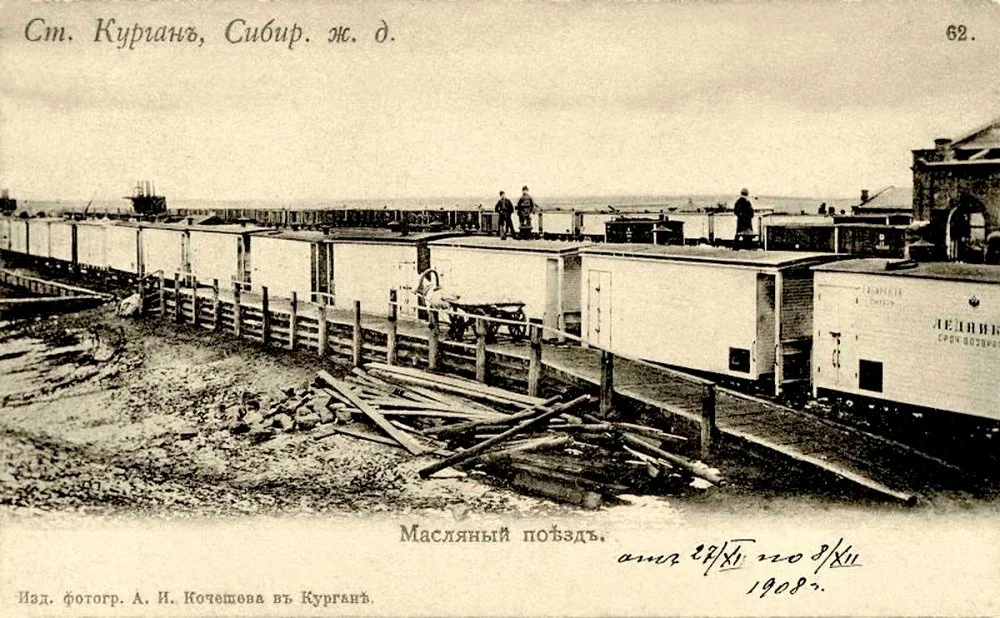

Train with refrigerated butter cars on the Trans-Siberian Railway. Kurgan. Early 20th century / https://www.charmingrussia.ru

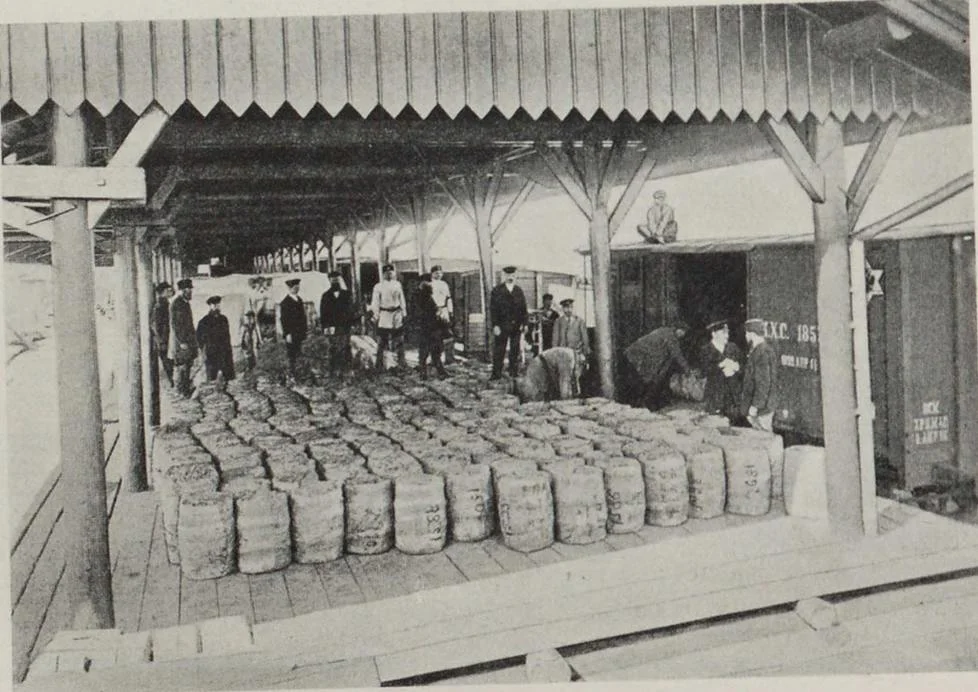

Most of this butter was sold via Denmark to Britain, which imported almost 25,000 tonnes in 1903. In many cases, it was labelled as ‘Danish butter’, often under the brand name Lurpak, which is still very popular today. Special butter trains, using refrigerated wagons and running daily in summer, transported the butter in beech barrels from Siberian railheads to the Baltic ports for onward shipment—in refrigerated steamers—to Copenhagen and Britain.

Butter shipment in beech barrels. Denmark. Early 20th century / https://lex.dk

For example, Barnaul, a major industrial hub on the left bank of the Ob River in southwestern Siberia, had fourteen butter export offices, mostly Danish or Russian, with two British businesses. Omsk had fifteen offices, half of which were Danish, with the remainder being Russian or German with one British office. There were also other offices located in Petropavlovsk, where there were twenty-six dairies. Most of these areas had once been the homelands of Kazakh nomads.

Mountains, Milk, and Markets

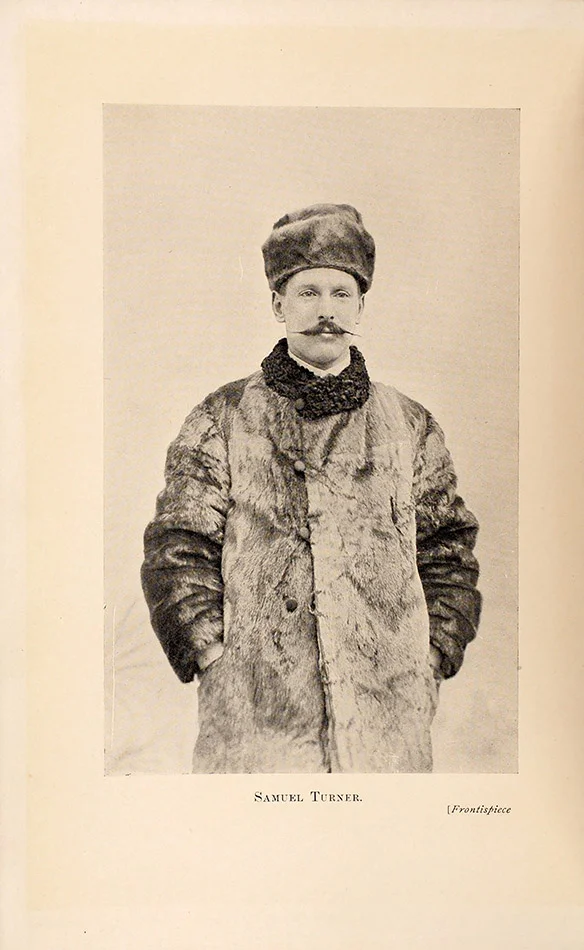

Samuel Turner was not only a butter merchant but also a highly experienced Alpine mountain climber. In the late spring of 1903, he visited Western Siberia to find out more about the burgeoning butter industry he had heard so much about in London—and to climb mountains in the Altai. His book remains a valuable source on both the butter industry and on the Altai Mountains.

Samuel Turner. London. 1911 / Photo from the book “Siberia: A Record of Travel, Climbing, and Exploration”

He wrote that within three years the import of Siberian butter had reduced the price paid by British consumers by 3 pence per poundi

I. Kocheshev. Delivery of milk to a collection point. Early 20th century / Wikimedia Commons

It was only the lack of a proper transport infrastructure that prevented the steppe butter business from expanding even faster. In some parts of the Altai, farmers had to transport their butter over 500 kilometers by sledge to Biysk and then another 650 kilometers by caravan to reach the railhead. Even so, it was still cheaper to transport butter across Siberia and Russia and then by sea to England than from Ireland to England.

Copper and Coal: The Mining Frontier

It is important to remember that it was not only butter that was being produced in southern Siberia. British and French companies had invested heavily into the extractive industries, particularly in the region around Pavlodar in what is now north-central Kazakhstan. Copper, iron, and other metal ores existed in great quantities in this region, and after they were mined, they were smelted into valuable ingots for export.

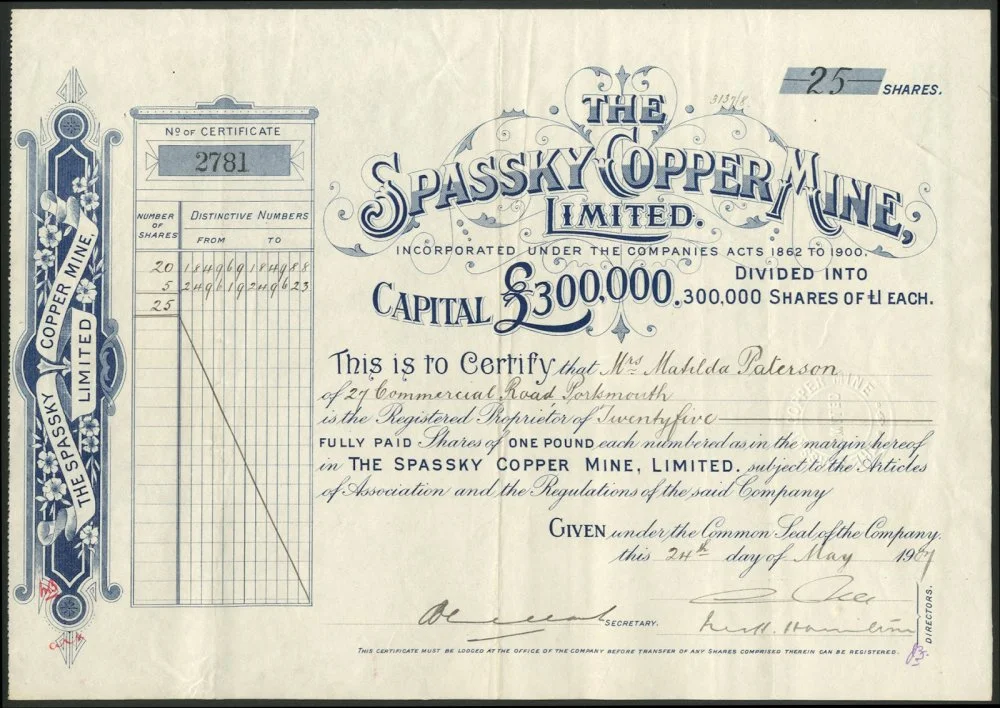

Shares of the Spassky Copper Smelting Plant. 1904 / https://www.scripoworld.com

As Henry Cooke notes, copper deposits were found throughout the steppe, with six mines in the Akmolinsk region in active production, yielding some 4,300 tonnes of ore and another 29 mines in Semipalatinsk producing another 3,700 tonnes of ore in 1901. Abundant supplies of coal, found particularly close to the Spassky Copper Smelting Works, meant that the industry could expand rapidly, and in 1904, British investors bought the Works. Cooke described the Ekibastuz coal beds located close to Pavlodar as ‘vast and inexhaustible’, and he also reported that the nearby Karaganda collieries had been bought by English interests. They produced almost 20,000 tons a year of coking coal for the nearby Spassky copper plant.

Life on the Edge: Engineers, Families, and Nomads

More details on the mining industry in north central Kazakhstan can be found in a book written by Edward Nelson Fell, who from 1902 to 1908 was manager for the London-based Spassky Copper Mine Company, which owned the copper mines in Uspensky and smelting works in Spassky. As he noted:

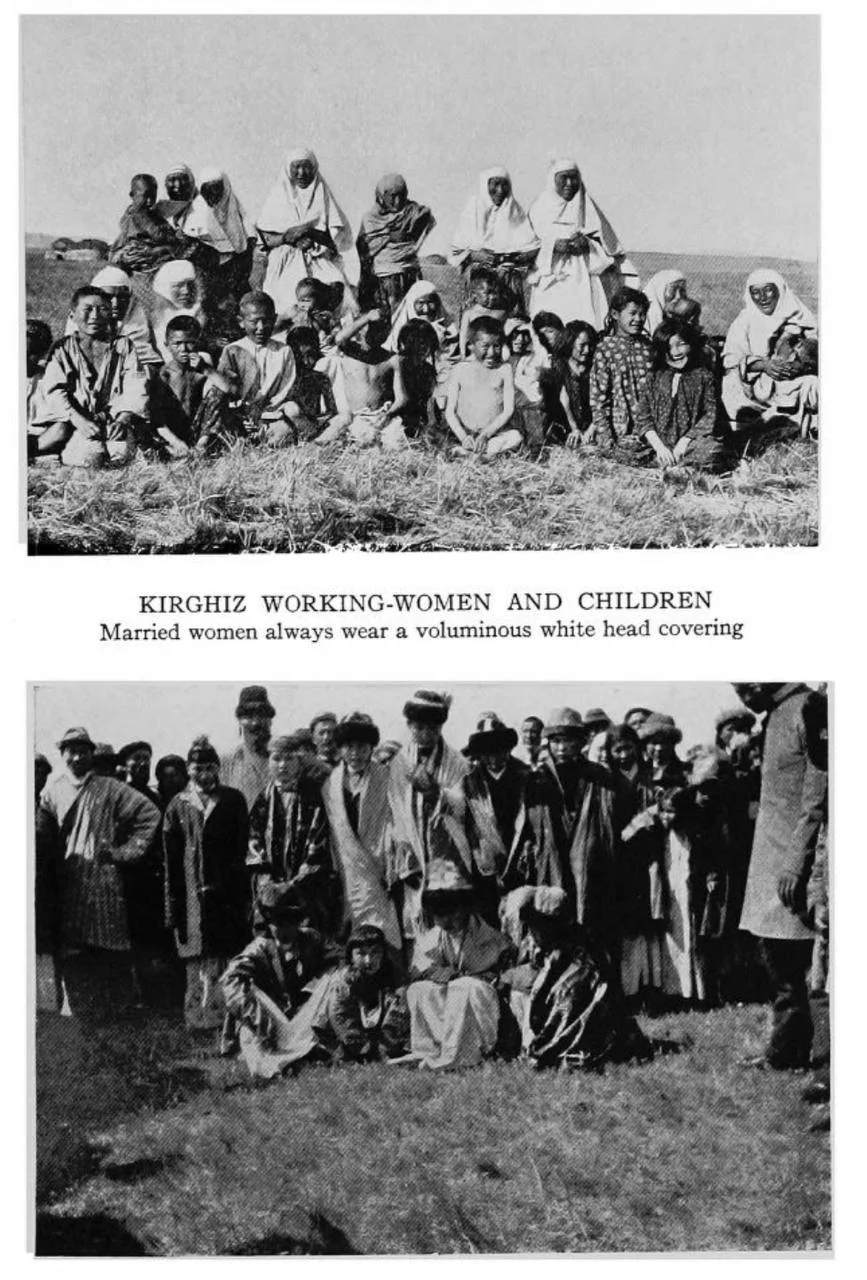

Before the coming of the Russians, this vast stretch of country was inhabited, or more properly speaking roamed over, by the largest branch of the Kirghiz race, calling themselves Kazaks, of Turkish-Mongolian origini

Fell said that until the early 1900s, there were no villages within 150 miles of the mines, but by 1909, the Russian government had made provision for the settlement of 25,000–30,000 peasants in the best river valleys near the works:

Villages were laid out and settled with Little Russians from the congested districts of southwest Russia, Poltava, Kharkov and Kiev. The Government carried them 2,000 verstsi

The nomads were pushed aside. Fell wrote:

It is hard for them to be expelled from their favourite pasture grounds by the newcomers. It is the old conflict between the free range and the farm.

Another of those who worked at the Spassky plant in the first years of the twentieth century was Frank Vans Agnew, who was also Fell’s son-in-law. He maintained detailed notes and diaries of his time at Spassky, and these were published in 2020 by Jamie Vans, his great-nephew. He describes family trips to the Altai Mountains, to Lake Balkhash and steamer trips on the Irtysh, the Volga and the Kama rivers. Like many English expatriates, he came to enjoy life in the steppe, particularly the traditional life of the nomadic herders.

Page with photographs from Frank Agnew’s diary / https://archive.org

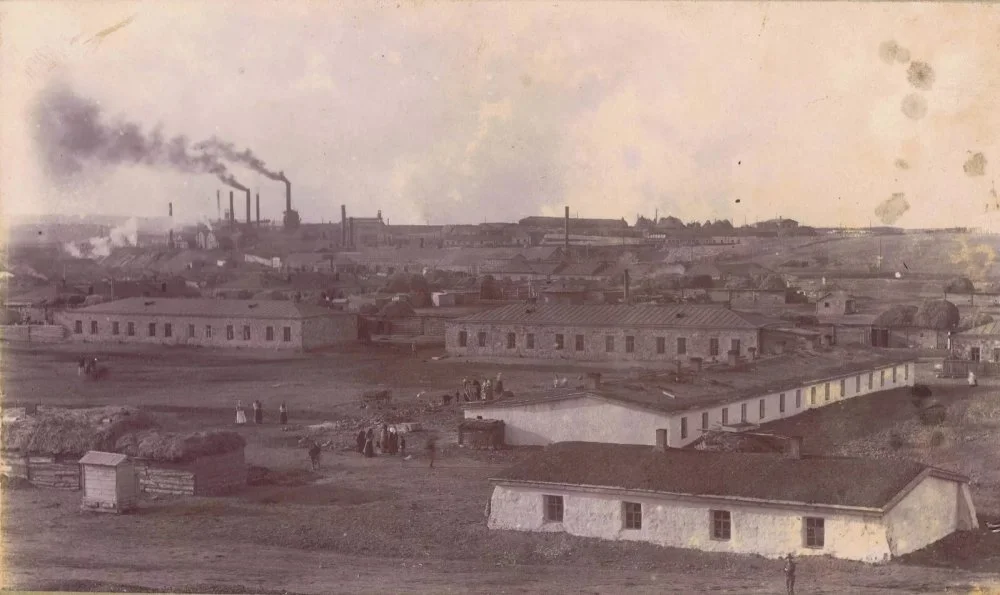

Remarkably, a set of photographs of the Spassky plant dating from the early years of the twentieth century has recently emerged at auction. They were probably taken by Stephen Lay, an associate of the Camborne School of Mines and Fellow of the Institute of Materials, Minerals, and Mining. The seventeen photos include pictures of the Spassky Smelter in 1913, a copper converter, the compressor room, quarry workers, the compressor plant, and so on.

Spassky Copper Smelting Plant. 1913 / Wikimedia Commons

Further details about the Spassky smelting plant and the copper mine can be found in British mining engineer John Wilford Wardell’s book In the Kirghiz Steppes, about his experiences of upgrading machinery there in the five years from 1914 until November 1919, when the upheaval of the Russian Revolution finally forced him to leave, along with all the British personnel and their familiesi

Wardell himself arrived at the plant in 1914 by tarantassi

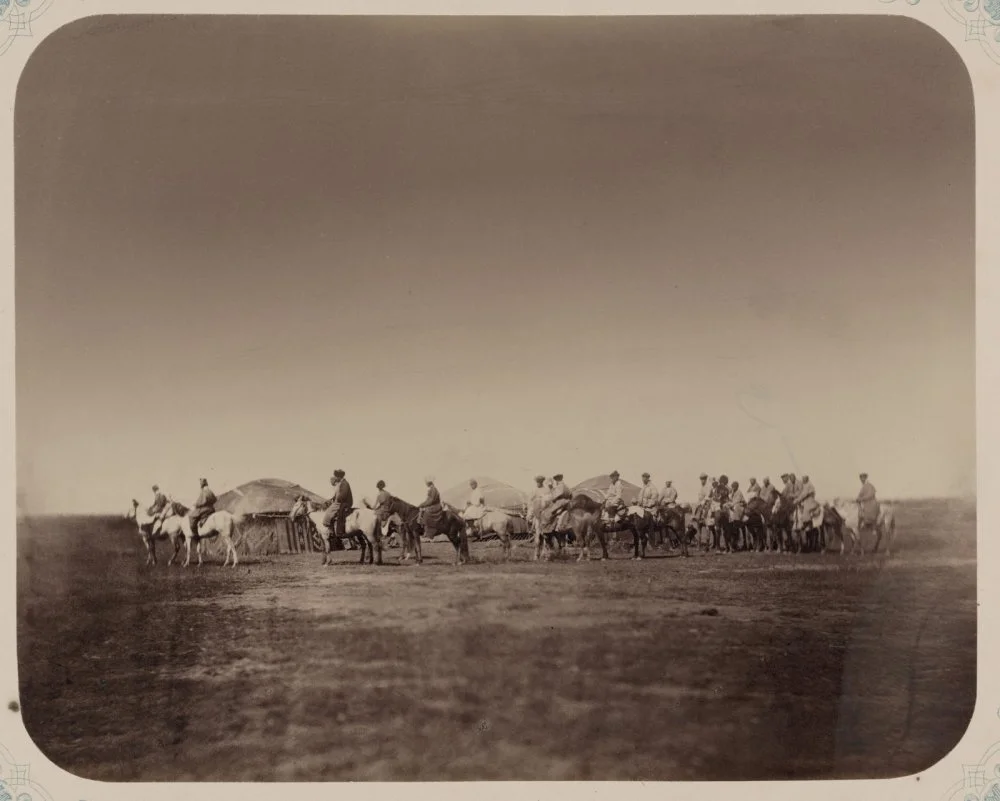

S. Dudin. Nomadic camp. 1899 / Wikimedia Commons

Wardell says that copper mining had been taking place at Uspensky for thousands of years, although modern mining started when the Ryazanov family bought the area from local Kazakhs in 1861, having already bought the collieries at Karaganda in 1856. They sold the whole enterprise to British interests in 1904, which ran them until 1919. Although a lot of high-grade ore had already been mined, there were still huge deposits in some places that made it worthwhile to mine and smelt it. For the six years from 1909 to 1914 (both years inclusive), approximately 149,000 tons of ore, which was on average 19 per cent copper, were mined, producing 21,800 tons of copper.

Revolution and Retreat

However, problems were growing, particularly during the latter years of the First World War, when Bolshevik agitators from the north became influential in the works. At first, the workers took little notice, but later, after the February Revolution, they began to respond and to form workmen and peasant committees known as soviets. But it was only following the October Revolution that things became difficult for the foreigners, mostly British, running the plant. The local soviets took over:

‘A workman could not be engaged, dismissed, fined, promoted or degraded without the approval of the local soviet and discipline suffered because the committee invariably upheld the workman against the administration,’ wrote Wardell.

As the security situation worsened, the Spassky Copper Mines were nationalized on 27 March 1918. Fearing for their lives, the British staff of ten men, five women and seven children decided to leave. They sold all their surplus effects and headed to Petropavlovsk by horse and cart, a five-day journey of almost 800 kilometers. From there, they intended to travel west by train to Moscow and then to Arkhangelsk and by ship back to England.

The smelter superintendent H.C. Robson’s wife and child arrived in Petropavlovsk on 28 May, and he was to follow shortly after. The town itself was in a state of siege and was under the control of ill-disciplined Red Guards, whilst the train station was controlled by the Czechs. On 30 May, the town fell to the advancing Cossacks and White Guard.

Red Army soldiers. 1919 / Wikimedia Commons

Early in July, the Cossacks retook control of Spassky. The British staff were encouraged to return to continue producing copper, a proposition they agreed to. The operations had been both badly neglected and damaged, and the mine was flooded. With difficulty, they were brought back into production. Apart from work, there was little the staff and families could do: they had sold most of their chattels before evacuating to Petropavlovsk. Basic supplies were difficult to come by and the local soviets were becoming increasingly assertive.

By mid-1919, the Red Army had advanced again, cutting off the escape route to the west. On 21 July 1919, the British consul advised the British staff to evacuate Spassky, only this time permanently. The plan now was to head east and then to escape by sea through Vladivostok or Shanghai. Robson and his wife reached Vladivostok in early September, where they met up with others who left before them, and decided to try and get a passage to Canada. They reached Vancouver on 16 November and after crossing to Canada, they headed across the Atlantic to London. Others, including Wardell and his family, headed to Shanghai and boarded a ship to Marseilles, before eventually arriving back in Southampton on 26 November 1919, some 16 weeks after leaving Spassky.

The accounts of these British butter merchants, engineers, and administrators about their experiences in the Kazakh steppe in the years between 1900 and 1920 throw a remarkable light on the tumultuous events that marked the beginning of the twentieth century. They witnessed the rapid industrialization of once-remote regions, the revolutions of 1905 and 1917, and the terrible consequences of war.

At the same time, they also experienced the traditional life of the steppe nomads, taking part in wolf hunts with eagles, pominka horse racingi

Preparation for kazak’s traditional horse racing (Baige). Turkestanskii al’bom. 1871–1872 / Congress Library

The Bolshevik Revolution finally brought this early phase of industrial development in the steppe to an end. Production halted for several years and was then revived at the end of the 1920s. Mining continued at Uspensky until 1964, when the mine was closed permanently, although large tungsten and molybdenum deposits were discovered in the mid-1950s. Today, many of the original buildings can still be found in the area, and some locals believe the old mine workings can once again be revived. Whether or not that happens, we should be grateful for the first-hand accounts of those who witnessed incredible events on the Great Steppe more than a century ago.