Ethnicity is a much-discussed subject in our world, and social scientists and historians have had much to say about it. Basically, their definitions usually derive from the European experience of nation building.

Ethnicity is a much-discussed subject in our world, and social scientists and historians have had much to say about it. Basically, their definitions usually derive from the European experience of nation building.

Ethnic groups, we are told, should have a common name, a myth of common origins, shared historical memories (with appropriate holidays), a common culture (language, customs, religion), a common territory/homeland—or at least a memory of a common homeland (which may often be in dispute with their neighbors)—and, finally, some sense of solidarity. In previous notions of modern nation building, these ties were seen as biological, that is, all the members of a group were believed to have descended from a common ancestor. This is the so-called ‘primordialist’i

Over time, historians and social scientists saw that there was much political negotiation that went into both nation building in modern times and ethnogenesis in earlier times. Nations were conceived of as ‘imagined communities’. They did not arise naturally from a pristine ethnic base but were ‘constructed’, usually by indigenous groups of intellectuals with political goals or governments. In many instances, people had to be taught who they were through national systems of education. Obviously, this could only occur with the advent of mass education and mass communications, and it is a relatively recent phenomenon. We need not enter into the battles between the ‘primordialists’, ‘constructionists’, and those deconstructing them except to note that they are increasingly now looking for common ground. Some nations do, indeed, have ‘deep roots’, but political manipulation in the shaping of their modern (and earlier) identities cannot be excluded. Due to new DNA studies, we have more data available to us now, but they still require further refinements with respect to defining ethnicities.

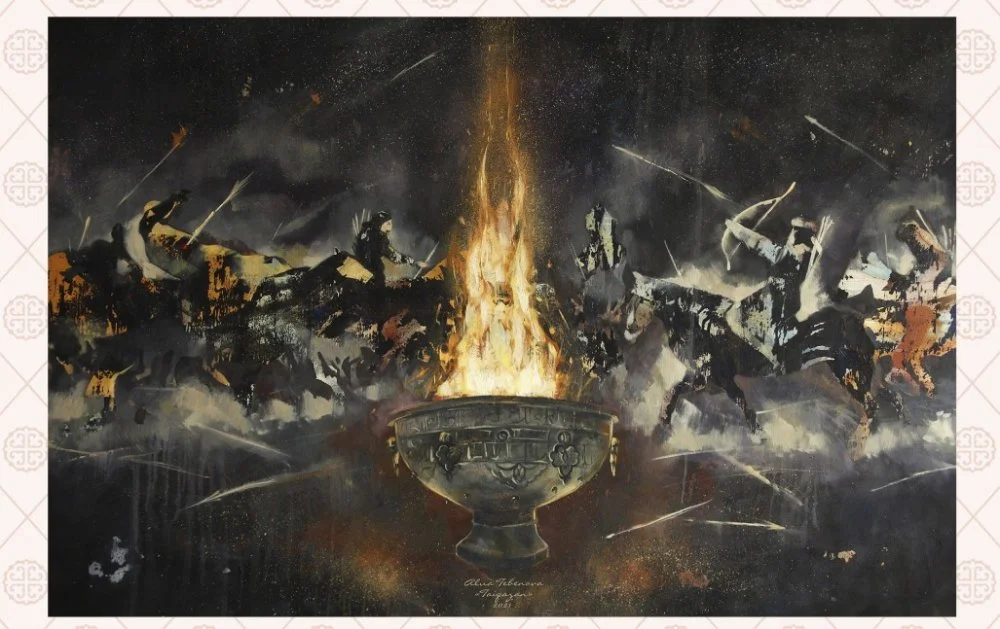

Armies on the march

There are many problems in applying these approaches to the world of the Eurasian steppe. Organized in tribes and tribal-like structures (terms that are subject to much debate among social scientists) and only very exceptionally in states, our nomads are hard to pin down. They moved easily from chiefdoms, complex chiefdoms to early states, xenocraciesi

They lived dispersed over extensive territories, requiring periodic migrations to fresh pastures. Those on the frontiers of powerful states/empires, in particular, had flexible political and ethnic loyalties. Indeed, tribes often form on the peripheries of empires and are sometimes molded by them to suit their purposes. Sometimes, tribal groupings, often brought together in confederacies by or in reaction to states, adopt a common name based on the politically dominant group and recalibrate their ethnogonic myths to suit the origin myth of the principal tribe: this is the ‘kernels of tradition’ model.

Some would argue that these were not peoples, but ‘armies on the move’, with fragile political loyalties and malleable notions of ethnic affinity. When tribal unions break up, older traditions and names resurface until the next union is formed, often with more or less the same components but now under a new name. We can observe this kaleidoscopic jumble across the frontier zone from the Roman world to China. Tribal society was fluid.

Alua Tebenova. Taiqazan, 2021

Political and ethnic loyalties may have had little hold on the rank and file, and sorting out who is who is not easy.

According to one recent calculation, during the first millennium CE, Chinese sources recorded some fifty-nine distinct ‘peoples’ in Central Eurasia but provide information on what language they spoke only for eighteen. Of the eighteen, only three can be identified with any degree of certainty. Archaeological finds, in the absence of written documents found in situ, are often not helpful as ethno-linguistically distinct groupings can share a common archaeological culture (for example, the Alanic and Bulgharic populations of the Saltovo-Mayatskaya culture in Khazaria).

As for shared historical memories, presumably, the ‘barbarians’, as their sedentary neighbors usually called them, had them, but these were rarely written down. Some were preserved orally, and hence subject to change. We have little directly from the ‘barbarians’ that was written down. Much of what we know comes from their sedentary imperial neighbors who disliked, feared, and oft-times simply misunderstood them—and sought to control them or buffer their borders against them. Where possible, they tried to shape the ‘barbarians’ into groups that made sense to them and could further imperial purposes. This is an old game, and empires have been playing it in their tribal borderlands for millennia. The modern states of post-Soviet Central Eurasia (for example, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan) are all the products of imperial manipulations by Tsarist Russia and especially the former Soviet Union. How does this work out for the steppe peoples of medieval Eurasia?

What truly bound these peoples together?

First of all, what really bound the medieval nomadic steppe peoples was not a common name, origin myth, or language—although we can see elements of such things peeking through the fog, and many spoke variants of a common tongue, Turkic. Rather, it was a habitus shaped by a shared culture of pastoral nomadism and the variants of a high political culture: the Steppe imperial tradition. They constructed a ‘reality’ of descent from a common ancestor and expressed their political ties in biological terms. Genealogies were manipulated. This was in a sense a ‘guided’, even ‘imagined’ primordialism.

This official image was in accord with ancient and medieval notions of nationhood prevalent among their sedentary neighbors. In reality, these ‘nations’ or ‘peoples’ were polyglot conglomerations that had joined a charismatic (successful) leading clan/tribe and adopted its ideology, political traditions, and name either voluntarily or by force. Ethnicity in this fluid population was a highly politicized process, and the peoples concerned were not the only actors on the stage. Ethnic identifications could also be shaped by one’s neighbors on several levels. First, there was alterity, the basic ‘we’ and ‘you’ juxtaposition. One’s response to the question ‘Who are you?’ often depended on who was doing the asking—and why—producing ‘situational ethnicity’. Second were the political goals of neighboring empires that regularly meddled in affairs in the ‘tribal zone’. As for memories of a common homeland, these are hard to come by in such a mobile society with multiple, shifting homelands, although the holy grounds around the Orkhon and Selenge rivers in Mongolia, political and spiritual centers for a series of states into the Chinggisid era, retained some hold. Moreover, such ‘memories’ were largely recorded by second or third parties.

Mahmud Kashgari's Turkic world map

The ancestral homeland of the Turks

The ancient Turkic urheimat (German ‘ancestral homeland’) appears to have been located in southern Siberia from the Lake Baikal region to eastern Mongolia, although arguments placing it well to the west of that area have been advanced. Urheimat-seeking is now quite unfashionable in some scholarly circles, and what we really mean here is that at a certain time and place, a grouping of people, very likely of diverse origins but now speaking a more or less common language, lived for a fairly extended period as a linguistic-cultural community. The ‘proto-Turks’ in their southern Siberian-Mongolian ‘homeland’ were in contact with speakers of eastern Iranian (Scytho-Sakas, who were also in Mongolia), Uralic, and Palaeo-Siberian languages. Turkic is traditionally accepted as a member of the Altaic language ‘family’. The latter is said to include Mongolic (in various forms historically and today, including ‘para-Mongolic’ or ‘Serbi- Mongolic’ or a grouping of cognate languages ultimately stemming from an earlier common linguistic ancestor but diverging from Mongolic), Manchu-Tungusic, and perhaps more distantly Korean and Japanese. With the exception of Turkic, all the other members of this family had their ancient habitats in Manchuria, with the Turkic-speakers immediately to their west. The ‘genetic’ view of Altaic (that is, derived from a common ancestor) has long been under assault, and many scholars now view the shared elements of vocabulary, phonology, and some grammatical forms as the result of centuries of borrowing and interaction. Some linguists have concluded that there is no Altaic language family at all, neither genetic nor melded, but simply a group of distinct languages that have borrowed from each other over the centuries. The academic wrangling over these languages is far from over, and these questions are far from academic. Of late, the more neutral term ‘transeurasian’ is being used instead of Altaic, with an even wider range of languages.

Language, as we have noted, is one of the key markers of ethnicity in modern times, although it was not necessarily as central to ethnic identification in earlier times.

Let us move the speakers of Turkic or ‘proto-Turkic’ out of the Siberian forests both literally and figuratively. You may have noticed that I am cautiously using terms such as ‘Turkic,’ ‘speakers of Turkic’, et cetera. This is because we are talking about the third and second millennium BCE, and the first instance of a people calling themselves Türk does not make an official appearance until the mid-sixth century CE. There were four stages in the shaping of the Turkic peoples of today. The first three were the results of the rise and fall of steppe-based empires (or xenocracies) and the migrations set off by each of these events in the Middle Ages. The last stage is much more recent, taking place in the twentieth century CE, and is associated with the social/ethnic engineering of modern states.

The earliest information we have on Turkic peoples is connected with the Xiongnu, a powerful nomadic empire centered in Mongolia that arose about 200 BCE, worried China for a while, and then collapsed by the mid-second century. Xiongnu ethnolinguistic affinities remain a mystery, but what we do know is that they extended their rule over a number of tribal groupings that in later periods are clearly Turkic-speaking—and presumably were earlier as well. Chinese Xiongnu, probably reflecting in Old Chinese, a name something like *hoŋ-nâ, is the source of the name Hun.

59

Chinese sources enumerate numerous peoples of Central Eurasia in the first millennium AD. However, only eighteen of them are known for the language they spoke, and only three out of these eighteen can be identified with some degree of certainty.

The Huns, who later appeared on the Volga River in circa 350, have some relationship to the Xiongnu/Huns of the Chinese borderlands or to peoples that were politically under their control. The appearance of nomads with one or another form of this name in Iranian, Indian, and Graeco-Roman sources, buttressed by recent archaeological finds and DNA data, make a reasonable but still circumstantial case for this connection, which has been hotly debated for the last fifty years. The name game is particularly tricky. The Byzantines, in time, labeled almost every grouping in the western Eurasian steppe ‘Hun’ (or ‘Scythian’).

The Xiongnu empire broke up in stages, and each crisis propelled peoples, including Turkic speakers, westward. More recently it has been argued that there was only one migration of Xiongnu peoples westward in the mid-fourth century CE. The European Hunnic state, forming after 375, was an ethnolinguistic hodge podge and the language of its Hun elite also remains a puzzle. About a decade after Attila’s demise in 453,1

The she-wolf and her progeny

The Türk tradition, preserved in early eighth-century CE Orkhon inscriptions, tells us nothing about Türk origins except that after the creation of the earth and humankind, Bumïn and Ishtemi (or Istemi) became Qaghans over humankind and organized the Türk nation. The seventh-century CE Chinese dynastic annals (the Zhou-shu, Sui-shu, and Bei-shi), all accounts completed just before or shortly after fall of the First Türk empire (552–630 in East, 659 in West), report a number of ethnogonic tales about the 突厥 Tūjué early Middle Chinese dwǝt khuat = Türküt [Türüküt] or Turkit mediated by the Soghdians. These tales were received from the Türks themselves or from the Soghdians, who often served as their intermediaries with China.

In these accounts, the Türks—and it must be emphasized here that they are only referring to the Türk people themselves and not other Turkic groupings—were an ‘independent branch’ of the Xiongnu who had earlier lived around the ‘West Sea’ (undefined but probably in East Turkistan, Mongolia, or Gansu). They were completely destroyed by a neighboring state. One boy, badly mutilated, was thrown into a swamp and survived thanks to the tender ministrations of a she-wolf (a common figure in Eurasian ethnogonic tales extending as far west as Rome). Later, the lad impregnated the she-wolf. When his enemies discovered that he was still alive and sought to kill him, the she-wolf fled north to a mountain in eastern Turkistan. There, in a cave, she gave birth to ten sons, one of whom took the surname Ashina. He became their leader and placed a wolf’s head on his standard to display his maternal origins. Their numbers grew through marriages with local women, and several generations later they left the cave and acknowledged the overlordship of the Rouran/Asian Avars, whom they served as iron workers. By this time, they were living on the slopes of the Altay. Rouran origins are often claimed to be ‘Mongolic’—and there is some evidence pointing in this direction. Another account, also in the Zhou-shu, places their home country, Suo/Suŏ 索 (Middle Chinese: sak = Saka?) north of the Xiongnu. Here, in a large family of seventeen (or seventy) brothers, only one of them, born of a wolf, proved capable of leadership. His oldest son, later given the name Türk, was made the leader. Türk’s son, Ashina, born of a concubine, was elected leader after his father’s death on winning a jumping contest. His grandson was Bumïn, the first Türk Qaghan, who is an actual historical figure. These are very different accounts, but both feature descent from a totemic female ancestor, a she-wolf. Ashina is the family name of the clan that leads the Türks. A Xiongnu association is noted. These conflicting tales probably point to mixed origins.

The Sui-shu offers us a less fanciful historical account. In it, the Türks are said to stem from ‘mixed Hu barbarians’, bearing the clan name Ashina, from the Gansu region. We

don’t know when the Ashina-Türk first appeared in the Chinese borderlands—perhaps it was after 265 CE, a period of mass migrations of the Xiongnu and other tribes from southern Siberia and adjoining regions. In the course of frontier turbulence, in 439, the Ashina with some 500 families moved to Xinjiang, and by 460 they had moved to the southern part of the Altay and submitted to the Rouran/Asian Avar, the dominant power in Mongolia. Here, we are told, they settled and were engaged in iron working, et cetera.

The Türk–Ashina relationship is not entirely clear. Were the Ashina merely a clan of the Türks? Were they a ‘foreign’ clan who became leaders? We don’t know. The name Ashina is not Turkic. It probably stems from east Iranian, perhaps Khotanese-Saka âṣṣeina/âššena ‘blue.’ In the Orkhon inscriptions (Kül Tegin, E,3/Bilge Qaghan, E, 4) mention is made of the Kök Türk or the ‘Blue Türks’, and Kök, it may be inferred, is probably a translation of Ashina. Other explanations have been offered: Ashina represents a Tokharian-based term *Aršilaš or ‘noble kings’, or it is connected with Tokharian arši ‘holy man’.i

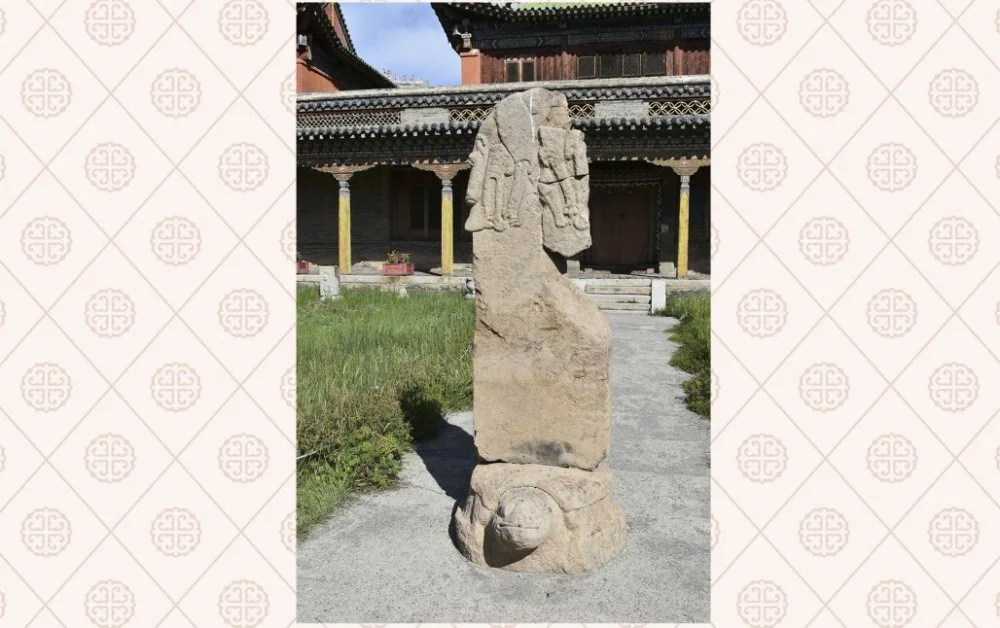

Bugut inscription/Richard Mortel/Flickr

Chinese sources also tell us that the word ‘türk’ meant ‘helmet’. In the Turkic languages, türk has various meanings, but not this. Khotanese Sakai

Tokharian loanwords in Old Turkic. We might add here that virtually all of the early Türk rulers have non-Turkic names. Thus, ever since they entered the stage of history, the people who bore the name Türk appear to represent an ethnically complex amalgam. The first official written monument we have from them (Bugut Inscription, 582), naturally, was written in Soghdian, the lingua franca of the Silk Road, with fragments of an inscription in Old Mongol (Rouran/Avar) written in the Brāhmī script.

By the 540s, the Ashina–Türks were in direct contact with northern China, ruled now by competing dynasties, the Eastern and Western Wei (themselves of foreign Xianbei/Serbi, para-Mongolic origin), each looking for allies in their tribal periphery. The Rouran/Asian Avar Qaghan Anagui (520–552), the overlord of the Türks, who was fighting to hold his throne, was doing the same as well. When the Eastern Wei made an alliance with Anagui, the Western Wei, in 545, formed an alliance with Bumïn, the ruler of the Ashina/Türks—Anagui’s subject. When the Avars refused Bumïn an Avar royal bride (in return for his help against the Tiele, another subject tribal confederation of the Rouran), the Western Wei happily sent him a Wei bride and Bumïn promptly revolted in 552, destroying the Rouran/Asian Avar state. Thus was the Türk state born, in an era of crisis in its overlord state and manipulations by neighboring empires. China was the midwife—it was a bloody delivery and the child proved to be troublesome.

The Türks rapidly conquered the tribes of the Eurasian steppes, forming an empire that extended from the Black Sea to Manchuria and ruling over a host of Turkic, Mongolic, Iranian, and other peoples. All of them, politically, became Türks. They also brought major portions of the Silk Road under their control. We need not dwell on the complex details of Türk–Byzantine relations and interactions with China, which had revived under the Sui and then the Tang dynasties. We will simply note that the Tang conquered the eastern Qaghans in 630 and the western Qaghanate by 659.i

In the course of this turmoil, a second wave of Turkic tribal groupings left Mongolia and the adjoining regions, migrated westwards to the steppes of Central Eurasia, and incorporated the other Turkic tribes that had been coming to the region since Hunnic times as well as Iranian and Finno-Ugric peoples. Although they did not form states, the political traditions of the Türk empire continued among them, albeit on a sub-Qaghanal scale. A lingering sense of Türk consciousness continued, at least on the cultural level, and was expressed in the literature produced by the Uyghurs (who had different core traditions of their own), written in what they called the ‘Türk language’ as late as the eleventh century CE and by the Qarakhanid realm, the successors of the Türks, who according to Maḥmūd al- Kāshgharī, writing in the 1070s, termed their language Türk. The tribal confederations, however, used their own ethnonyms (including Qarluq, Oghuz, Kimek, et cetera).

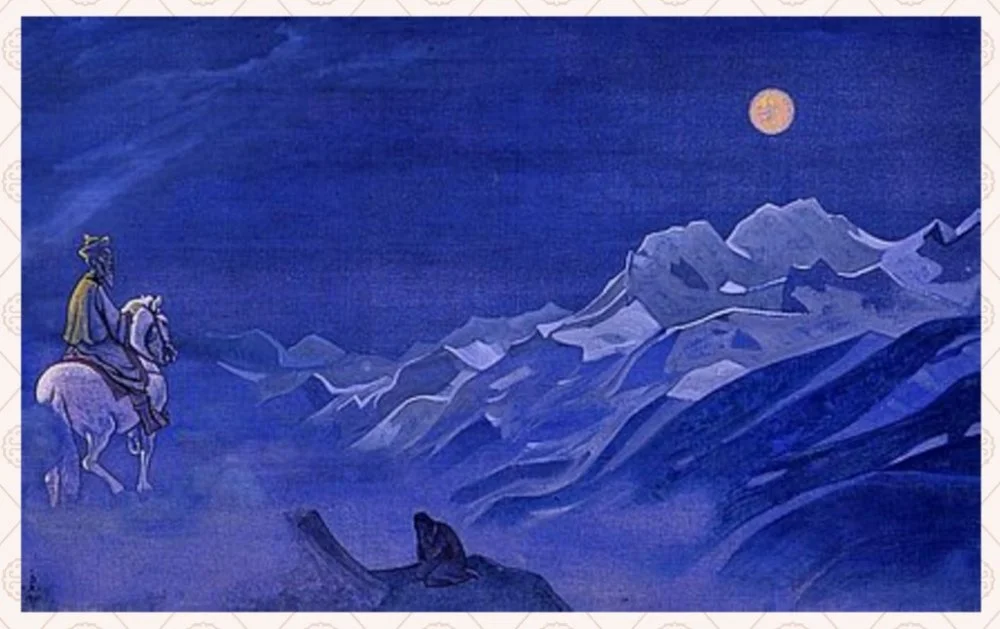

Alua Tebenova «Horseman», 2019

The Turkicization of Eurasia

These Turkic peoples were overwhelmingly shamanist, but they had been in contact with variants of Zoroastrianism,i

Ethnonyms take shape in multiple environments, in both that of the ‘host’ and that of the ‘significant other’, often a major neighboring state, and this was certainly true of the Turkic world. Internally, they were still fully aware of their differences in dialect, culture, and of those who were Turkicizing, but to the outside world, they were all ‘Turks’ and they accepted this identity in a Muslim milieu.

This leads to our next stage. In the early thirteenth century CE, another series of migrations in the steppe was set in motion by the Mongol conquests. Chinggis Khan was aware of the Türk imperial model and cognizant of the complexities of controlling mobile tribes. He, having masterfully used the system, set about dismantling the old tribal order. Tribes were broken up and parceled out to the various personal armies created for his sons. The whole Eurasian tribal world was thrown into turmoil. The loyalty of the tribesmen was to be directed towards the altan urugh, the Golden Clan of the Chinggisids, not their now dispersed tribal leaders. The components of most of the Turkic peoples of Central Eurasia (and the Middle East) today reflect this program of breaking up and redistributing the tribes. In Central Eurasia, Turkic-speakers outnumbered the relatively small numbers of Mongols who remained in the region, and Turkic, in one form or another, became the lingua franca. Thus, the Mongol conquests completed the Turkization of much of central Eurasia as well. The various Chinggisid polities clashed, divided, reconfigured themselves, et cetera. The bulk of the Turkic world entered modern times under the leadership of one or another descendant of the altan urugh—with the very considerable exception of the Ottoman empire, which had nonetheless begun as a frontier statelet of the contracting fourteenth-century CE Chinggisid world.

Nicholas Roerich. Forging the sword. The Nibelungs

Nation-building in the empire

In western and central Eurasia and Siberia, the various Turkic peoples were brought under Russian rule from the sixteenth through to the nineteenth centuries CE. The tsarist government, like other empires of its time, began to map their alien subjects (инородцы) and give them fixed names so that officials could deal with them, which was not an easy task. Some of this population was still highly mobile. Some had multiple names, and others lacked a common name. For many, especially when dealing with ‘outsiders’, religion was the most important marker of identity. The bulk of the Turkic peoples were Muslim, ranging from those who were deeply versed with Islam to those who were still largely shamanists with an Islamic veneer. Many that are today recognized as one people would have hardly considered themselves as such then. The ‘real’ Uzbeks (Özbeks), who conquered Uzbekistan in circa 1500, are today largely in the northern parts of the country that bears their name, and they speak a form of Turkic that is much closer to Qazaq (Qïpchaq, a northwestern Turkic language) than to official Uzbek (a ‘Türkī’ or southeastern Turkic language). The latter grew out of Iranized dialects of the old Chaghatay language, shaped under Mongol and Timurid rule.

In the past, Özbeks despised the Sarts, people of Turkic background that had sedentarized or sedentary Tajiks who had Turkicized but were now also officially ‘Uzbeks’, and considered themselves distinct from Chaghatays, Qarluqs, and other remnants of pre–1500 Turkic populations. Bilingualism (Tajik and Uzbek) is common in the cities. Their western neighbors, the Türkmen, in the nineteenth century CE, were divided among five different political entities: some were ‘subjects’, rather obstreperously, of the Bukharan amirs, others of the khans of Khiva, yet others of Russians and Persian rulers. They raided and plundered everybody, and dividing lines were obscure. Some Türkmen sometimes called themselves Uzbeks . Sometimes, they simply would not answer government officials or ethnographers inquiring about their identity. Some tribal groupings had the same name but spoke different languages and had different customs, yet claimed to be one and accepted the others as such. Others with the same name did not. The Qazaqs were called Qïrghïz and the Qïrghïz were called Qara Qïrghïz. The Soviets decided who would be who—but it was not an easy task—and they had a political agenda as well, driven in part by fears of the unification of the various Turko-Islamic peoples into a ‘Turkestani’ state.

In 1921, a group of East Turkistani intellectuals decided to revive the long-forgotten name Uyghur (not in use since the sixteenth century CE) and applied it to the sedentary Turkî-speaking groups of Xinjiang (of mixed Turkic, Iranian, and Tokharian ancestry) who up to then had identified themselves by locality. Thus, were the Uyghurs ‘reborn’. After the Russian revolution, a group of Siberian Turkic intellectuals from various clans to which the Russians had given the name Abakan or Minusinsk Tatars (they had no common name) decided to declare Khakas their national name (they had been given an autonomous region and needed a name).

Oirot-messenger of the White Burkhan. N.K. Roerich 1925 /Alamy

Someone had read Bichurin’s2

Ethnogenesis is not finished. It never really is. The Turkic peoples of central Eurasia today are shaping new identities for themselves, sometimes reviving older traditions, sometimes retaining ‘traditions’ created by the Soviets, and sometimes creating new traditions. History, of course, is being used and abused—as it always has been in the shaping of ethnicity.