Written by Qalam’s regular contributor, film historian Alexei Vasilyev, this series of essays explores the oeuvres of the greatest Eastern film directors from different times. The portrait gallery continues with the Korean director Kim Ki-duk.

Even four years after his death, Kim Ki-duk’s name remains both a blasphemy and a prayer on the lips of world culture, pronounced along with the diametrically opposite reactions of either spitting or gasping. The engine that propelled Korean cinema onto the rails of global film festivals and box-office success in the early days of the twenty-first century is at the same time a shame and a disgrace to Korea. He caused a sensation with a film in which a woman tortured her vagina with a fishing hook, immortalized himself with a Buddhist parable about the inexorability of sadism, and stunned audiences with a film about the adventures of a young man whose mother cut off his penis and whose father sought ways to sew his own penis onto his son. He engaged in self-destructive behavior, recorded it on camera, and disappeared for a while. He finally returned three years later, having spent some time as a drunken, memory-hugging, reproach-spewing, childhood-dream-abandoning version of himself, to win the first grand prize in Korean history at a major international film festival.i

Director Kim Ki Duk is photographed for The Hollywood Reporter during the 70th Venice International Film Festival on September 1, 2013 in Venice, Italy/Fabrizio Maltese/Contour/Getty Images

ALMODOVAR AND THE PET SHOP BOYS—KOREAN STYLE

Kim Ki-duk shared a common theme with Genet and Fassbinder: the underworld. The dark spaces inhabited by convicts, repeat offenders, thieves, thugs, debtors and loan sharks, and pimps and their sex workers is the universe of most of his films. The opening shots of Kim Ki-duk’s first film roll are like an earthquake: a noisy splash, an emerald-green column of spray, the faces of three men—an old man, a boy, and a man with a shaved head—framed in the rays of flashlights, staring intensely into the turbulent river at night. The pulsating soundtrack of a porn movie nearing its climax, combined with quacking funk guitars reminiscent of the Japanese film Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds, sets the scene for Crocodile (1996). The guy with the shaved head rips off his wifebeater and camouflage pants, his tight body, with its muscular ass long used to sexual exertions, glistens under the bridge.

Crocodile. 1996/From open sources

That ass belongs to actor Cho Jae-hyun, and it would work tirelessly in Kim Ki-duk’s films for another five years, slapping women’s thighs and electrifying the men in the audience for wild nights, until Kim and he erected a monument to testosterone in Bad Guy (2001), a film about a pimp who turns a girl who responds to his kiss with a slap into a sex worker, thus making her fall in love with him. To tie up, to make one fall in love through continuous fucking, is a motif Kim borrowed from Pedro Almodóvar’s best film, ¡Átame! (1989). The characters played by Cho in Kim’s films of that time are actually exactly like the characters played by Antonio Banderas in the young Almodóvar’s energetic films like Law of Desire (1986) and to some extent Labyrinth of Passion (1982). Between ‘I want’ and ‘I will’, they do not experience any hesitation, and they seize everything as soon as they start salivating, like wolves seize their prey. Cho bursts into Kim’s second film, Wild Animals (1997), brandishes his fists and breaks the nose of a friend peacefully painting in an art class. When blood splashes on the friend’s palette, Cho dips his brush in it and finishes the painting: the fight actually started when Cho’s character walked in and immediately started criticizing the painting, demanding that more red paint be added. When he is thrown out, he does not spend much time rubbing his bruises in the hallway. When he sees students’ paintings stacked against the wall, he gathers them up and, now cheerful, goes to Montmartre to sell them.

Similarly, the ‘Bad Guy’, springing through a city crowd to the soundtrack of whistles and guitar during the opening credits, turned off a street, and stuck his tongue down the throat of a girl he’d never seen before simply because the blue calico of her white polka-dot dress was like a refreshing shower on a weekday afternoon. Likewise, the character ‘Crocodile’ picks up young ladies on the street and immediately starts beating them up. The movie is not about a monster in the river but a homeless guy with such an irrepressible and uncontrollable appetite that he disgusts even small-time gangsters, earning himself the nickname Crocodile. He is the lowest of the low—he lives under a bridge frequented by suicidal people, waiting to pick the pockets of victims before the police drag them out. He is both a looter and scavenger: when a beautiful girl jumps off the bridge, he thinks he might get more than a full purse. Thus, he fishes her out, keeps her intact, and spreads her out on his dirty mattress like his own private living doll.

‘We’re lying in the gutter, but we’re looking at the stars’ goes a line from a Pet Shop Boys song that perfectly describes the world of Kim Ki-duk’s early work. The mattress is dirty, but it’s the only place where, unbeknownst to the guests, you can see the hotel lights in all their seductive glory. The sex scene, long, detailed, and dashing in its primitive bravado, in which the woman stops pushing Crocodile away, having had the time over the course of the film and her life under the bridge to appreciate his guileless disposition, giving herself without restraint, is set to a melodic female vocalization à la Serge Gainsbourg. Here, we meet Kim, the model romantic of Gen X.

Korean director Kim Ki Duk gestures on the beach during the Asian Film Festival in Deauville, western France, 11 March 2004. His film "Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter.. and Springs" opens the festival/Jean-pierre muller/Afp/ Getty Images

But Kim Ki-duk’s films only began making the rounds of the festival circuit on the eve of the millennium, when the ‘whateverism’ of the Gen-Xers was already a thing of the past. By the year 2000, European audiences were still adjusting to the now-familiar rapid change of eras and generations, experiencing nostalgia for the past that came up unexpectedly. The fact that the favorite stories of their youth were now being played by Koreans, whose faces were unfamiliar to the West and, therefore, seen from their point of view as provincial, gave Kim Ki-duk’s films a welcome dash of spice. The old style of Almodóvar and Carax’s was no longer popular. And when performed by Asians, the old stories like mutton took on the piquancy of young lamb. What would have been inexcusable in Banderas’s case was exciting in Cho Jae-hyun’s performance. Almodóvar, Carax, the Pet Shop Boys—that was real youth. Now those who had grown up with those songs and movies have grown up: at the age of thirty, additional fantasy and stimulation were needed.

Kim himself made no secret of the fact that he was energized by the postmodernism of the 1980s, with its yearning for the marginalized, its ironic simplification of plots, its piquancy and even fustiness of sexual desires, resulting in wild, simple, and, therefore beautiful, like the appearance of flowers and fruits on plants, kinds of sexual intercourses. This postmodernist energy of the 1980s led him to call upon the icons of French postmodernism for his second film, which he shot in Paris. Denis Lavant, who was Carax’s signature actor, and Richard Bohringer, from the trendsetting film Diva (1981) by Jean-Jacques Beineix, played the main roles in films involving squats, Asian and African heroines, and criminal intrigue around the copyright of a music recording. In fact, Kim only learned about postmodernism in the 1990s, and was, in that sense, very typical of his country, which continued to cook in purely Asian juices until the 1988 Olympics.

A MARINE IN PARIS AND MOVIES FROM THE POINTS OF VIEW OF FISH AND DOGS

Kim Ki-duk spent the first half of the 1980s serving in the South Korean Marine Corps, an experience he put to good use in his film The Coast Guard (2002). He then lived in a temple for two years and seriously considered becoming a monk, which lent credibility to Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring (2003), which remains his most palatable film as far as international audiences are concerned. He moved to France to study fine art only in 1990, but he actually spent three years selling his own drawings in Paris and on the coast during tourist season. Male and female protagonists, whose hands are always busy with pencil sketches, remained an obsessive motif in his movies, from his first Crocodile to the Kazakh Dissolve (2019), where not only does the character of Dinara Zhumagaliyeva draw manga, but the actress herself—whose meeting with Kim at a master class in Almaty in 2011 triggered the whole production—was also seriously interested in it and had studied animation at university.

In Paris in the early 1990s, underground cinemas played all the great movies all the time for years, and Kim was introduced to all the riches of European cinema of the 1980s. His experience of these films was similar to the cultural changes taking place in the late and post-Soviet period. Thus, it is no wonder that Kim did well in this environment and has always been more honored there than in the West. He participated in various film competitions in Moscow when he was still unknown in Europe and also when they didn’t want to know him anymore. He found a home and a vast space for creative stimulation in the former USSR when there was no space for him in the Western sphere in the aftermath of the MeToo Movement. To be fair, in 1981, the Moscow International Film Festival was also the first at which Diva was screened—it was immediately distributed and became a favorite with young Soviet non-mainstreamers.

But even nostalgia about his early screenings from 1981 apart, even from a new perspective, is hardly enough to propel an entire country, South Korea, into the elite circle of uninterrupted circulation at the most prestigious film festivals. In his third film, Birdcage Inn (1998), which marked the beginning of Kim’s festival success and which can be seen as the precursor to the current Korean boom, the director delved into a genre that, along with lowlife romance, would become his favorites: the sea tale. These are films set by the sea, as in Birdcage Inn, or, even better, on the sea, like in the floating village of fishermen’s huts in The Isle (2001) and the rusted schooner that never docks, where visitors from the city come by boat to fish in The Bow (2005).

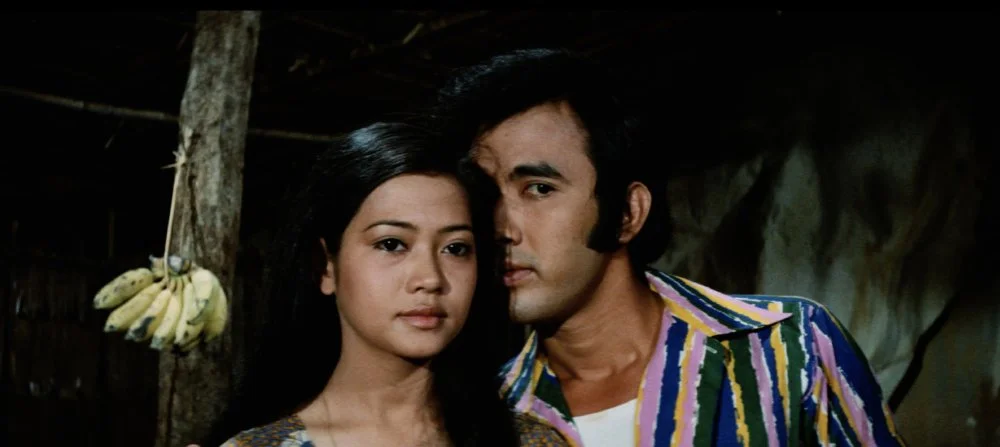

Not only the genre but also the style—lazy music, love triangles, long gazes leading to bloody and violent actions, brutality, semi-mystical elements, all kinds of witchcraft, fortune telling, et cetera—is not new to the Asia-Pacific region. The exquisitely beautiful two-part Thai widescreen film Choo (1972), directed by Pieak Poster, was a huge success in the USSR under the title Violated Loyalty. However, it was only in the last decade that French film connoisseurs even rediscovered, restored, and revered it. In the 1970s, they were far from the Soviet multipolarity in terms of cultural exchange, and thus Kim, who had experimented with his love of postmodernism in Paris, returned to his roots in Birdcage Inn. Roots, as is always the case, helped him become a universally understood and accepted artist.

Choo The Adulterer. 1972. Thailand. Directed by Piak Poster/Courtesy of the Thai Film Archive

In Birdcage Inn, a sex worker plied her trade in a shack on Pohang Beach, with its stone palm jutting out of the sea, and had sex with a net mender in camouflage pants on the creaky springboard of a rusty tower. The fixer takes down her overreaching pimp while the other sex workers in blue and red dresses sit in a perforated boat, their feet tapping in the waves. Kim had set up the camera half underwater, observing the tropical paradise from the point of view of a merman or, if you will, an orca.

At the premiere of The Isle in Venice, young women viewers were fainting: to hold on to her lover, the caretaker of a floating fishing village stuck a fishing hook in her crotch and pulled the line. At the same time, the male viewers grabbed at their throats because half an hour earlier, the hero, in an attempt at suicide, had done the same to his own throat. Needless to say, he couldn’t speak afterward, which would become a hallmark of many of Kim’s characters, such as the ‘Bad Guy’ or the death row inmate in Breath (2007). Here, however, the excuse of the plot allowed Kim to give the character the expressive gaze of Taiwanese idol Chang Chen, who wowed the world in the late 1990s in such cult hits as Wong Kar Wai’s Happy Together and Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Over time, however, the narrative excuses for his characters’ silence became less brutal.

In Kim’s most harmonious film, 3-Iron (2004), which won the Best Director award at the Venice International Film Festival, a wife, tired of snapping at her husband, happily becomes the wordless companion of a boy with a pompadour hairdo and the inscrutable, impenetrable appearance of the hero of Korea’s longest-running TV franchise, School. His lifestyle forced him to be silent as he lived secretly in apartments whose owners were away on vacation, so he had to pretend that no one was home.

Some directors like Eric Rohmer are masters of the conversational genre, but for Kim Ki-duk, conversations are longueurs that drag the movie out and delay the action. The Isle, where the protagonist would rather open her mouth to pour an extra glass of booze into it than explain herself, and the hero just can’t speak from the middle of the story, is open to many interpretations. Essentially, it illustrates Kim Ki-duk’s trademark trick, which surprisingly later also became a trademark of Korean doramas—for two people to become attached to each other, it is necessary for one to become completely dependent on the other’s favor and for the other to show this favor to the fullest (Moorim School, Jealousy Incarnate, True Beauty). Another aspect is that Kim’s characters are often well aware of this law and provoke this codependency themselves: the heroine of The Isle cripples herself, the ‘Bad Guy’ plunges the girl he likes into debt and chains her to a bunk, the working tool of a sex worker (this invention of Kim’s had an echo in one of the most poignant, and also quite provocative, doramas, School 2013). However, the most elegant interpretation of The Isle was probably the review by director Mikhail Brashinskiy, who claimed that the movie was shot from a fish’s point of view. In fact, The Isle is not only a movie with wordless protagonists—Kim uses the central, form-shaping angle he used in the final scene of Birdcage Inn, shooting with a camera half submerged in water. Strange and often brutal human interactions, which can have perfectly practical motivations—such as survival, escape from persecution, symbiosis—seem, when seen from the fish’s point of view, like we are watching an educational program about the underwater world, where the narrator explains the not-always digestible miracles using the laws of survival and adaptation. The fact that humans are brutal to fish is illustrated by another hotly debated scene in which a man catches a fish, cuts sashimi off its sides, treats his girlfriend to it, and then releases it. Remarkably, the fish swims safely with its exposed bones for half the movie, where, to the protagonist’s surprise, it is caught again, revealing its inappropriate likeness.

If The Isle is a movie made by fish, then Address Unknown (2001) was surely made by dogs. In it, Cho Jae-hyun plays a man named Dog Eyes: he slaughters and skins dogs for the local tavern, and the people in this movie are as ruthless to them as they are to the fish in The Isle. The action takes place in the fall of 1970 in a village near an American military base, and the fates of the inhabitants and the soldiers are intertwined like in a good TV series. The movie starts with fast-paced scenes of various characters waking up. The wooden house of the film’s only somewhat normal family features a unique camera angle: a static camera placed on the floor. This is known as the ‘Tatami shot’, and it was popularized by Yasujiro Ozu, the great Japanese film director of the 1930s–50s. It offers a viewpoint like that of a dog with its snout resting on its front legs, a perspective shared by the family's own pet.

Address Unknown (2001)/From open sources

The scenes themselves change so quickly, and the characters’ actions are so devoid of reflection that the constant flickering of actions and locations—the characters scurrying around the village after each other—is like the fidgety behavior of a dog who must mark all the trees, sniff under everyone’s tail, eat something, bark at someone, snuggle up to someone. One from a group of boys who studied in America is bullying a quiet boy. The bully is then subdued and held back by a huge boy of mixed race, who has witnessed the scene, so that the quiet one can strike back. The quiet guy lands his first few blows awkwardly, but then becomes so ferocious that the mixed-race boy has to pull him away from the bully. After having been of help to the quiet boy earlier, the mixed-race boy is accused of purse-snatching at his place of work. Frustrated, he goes home to see his mother, who, it turns out, has been caught stealing cabbage from their landlady’s garden. The argument turns into a fight, and the mixed-race boy now has to restrain his mother. He takes her back to the old red American bus, left to them by his Black soldier father, where they live, and starts beating her up. In the course of the fight, her breasts are exposed, and she slips away from her son; she climbs onto the roof of the bus and starts taunting him. The quiet boy, who had come to thank the mixed-race boy and witnesses the scandal instead, now drags him away, their roles reversed. Dog Eyes, the mother’s pre-war boyfriend, chases the mixed-race boy on a motorcycle and, after catching up with him, beats him up. He then returns to the bus to comfort the mother, but she turns on him instead, screaming, ‘Don’t you dare touch my son!’ A frustrated Dog Eyes goes home to shoot another dog, but the boy of mixed race, having lain in wait, disarms him, puts him in a cage, and strangles him with a rope. In an attempt to escape, the boy steals Dog Eyes’ motorcycle, but the bike suddenly flips over in the middle of the road and sends him crashing into a field, leaving his legs impaled in the ground like a pair of scissors. This bizarre and gruesome scene mirrors the iconic death scene depicted in the legendary post-war Japanese mystery novel The Inugami Curse (1951) by Seishi Yokomizo. Incredibly, this whole scene takes only ten minutes to unfold—even a dog would not need any longer to carry out such a sequence of events.

TO SPITE HITCHCOCK

In most of his films, Kim Ki-duk’s characters seem to experience no delay between impulse and action. While Bad Guy immediately kisses a girl he finds attractive on the street, her boyfriend just as immediately grabs a spittoon and beats Bad Guy over the head with it. This reflexive action is like a clown gag and provokes laughter, but it also helps Kim avoid being boring when the action revolves around a few insignificant events. When François Truffaut interviewed Alfred Hitchcock, the great master explained his methods of screenwriting, which have been adopted as the standard by inexperienced people ever since. For example, Hitchcock said that there could not be a scene where the male lead comes to the female lead’s house, rings the doorbell, and she opens the door. It would be better to insert a conversation with the concierge, who would say that he hasn’t seen her for three days, the hero will have to smoke nervously in a bistro, watching some suspicious guys, and then, already excited and desperate, he will accidentally meet his girlfriend at a flea market, where she is peacefully choosing decorative accessories for the house. Kim, however, does away with all these niceties. His method is exactly the opposite, as is perfectly expressed in a scene from Wild Animals, when the female protagonist’s father goes to her home to ask her for money. Meanwhile, at home, she is amusing herself with Denis Lavant, who has put his head under her T-shirt. When the doorbell rings, she runs to the door, Lavant trotting in front of her, his head still under her shirt. The father asks for money, the T-shirt rises immediately, and Lavant jumps out at him from his daughter’s bosom, screaming, and chases the swindler away. Kim’s films don’t have the usual tropes like ‘the father came to his daughter’s house and a strange man came out of the bedroom’, nor do they have any other circumlocutions. Yes, the daughter is at home, the man heard everything, and he only needs to pull up the daughter’s T-shirt to yell at the father, at which point the father will immediately realize that the daughter has a man, and an aggressive one at that. Thus, it is clear to all three participants at once, in one shot, what the dynamic between them is. And, as I said, and this is important, it’s much funnier that way.

In Address Unknown, Kim’s method was applied to a nostalgic melodrama, and for the two hours of the film, the viewer never loses interest for a second. After Address Unknown, as quickly as his characters go from bad to worse, he made Bad Guy, one of his few happy films—along with Birdcage Inn, 3-Iron, and The Bow—in which he finally seems to find a balance in the dualities that had always tormented him. He had always grappled with the biological determinacy of the flesh and the impulses of the soul (in which, as he grew older, he also began to discover biological determinacy—to his great disappointment and no less great confusion), as well as the duality of male and female dynamics. It should be noted that the protagonists of his sea tales are always women, while the men feature in the urban lowlife romance, in which they are often associated with the river. Crocodile sleeps and works under the bridge over the Hangang River, while the hero of Wild Animals, Cho Jae-hyun, not only lives on a barge but also commits murders with the sole purpose of preserving the barge. I’m not sure if there’s any intentional symbolism here (man as river, woman as sea); I’d rather attribute it to the subcortex of his brain, a more ancient entity than any Jungian myths. Still, such naive symbolism would have suited Kim very well. To a certain extent, despite having developed a mastery of the art of directing, he remained a penniless street painter, selling his work in Montmartre.

The Bow (2005)/Alamy

In Bad Guy, Cho Jae-hyun gives his best performance as a guy who has lost his vocal cords in a street fight. Only once in the film, in the interest of comic contrast, does he try to crow about love in the manner of a horny rooster. His legs, in sweatpants, are set widely apart; he tosses his cigarettes out with relish; he has the unwavering gaze of an abandoned dog so wild that he could be the leader of a pack of wolves, and yet he hasn’t stopped looking into the night for his lost master. In the same vein, Seoul has never been and will never be so appealing in Kim’s oeuvre again. The city comes across as a vibrant, pulsating heart, and the rhythm of the crowds is hypnotic, especially knowing that you can, unlike all those people, always make a detour to a rooftop with umbrellas and, in the pouring afternoon rain, have a shot of rice vodka with your buddies. The inviting green neon of the evening windows, behind which the three best things in the world—money, sex, and true love—await Guy every night. When a girl, who has known many men and almost lost the only one who cared for her, returns his feelings, he takes her to the seaside—to the same rusty tower trampoline that creaked so peacefully under the sex worker and the nice fishing net mender in Kim’s first sea tale, Birdcage Inn. Here, on the shore, between the city and the sea, the idyll at the end of the movie will engulf them.

In this film, Kim is already free of his fascination for European postmodernism; his technique has festival audiences not only gasping about fishing hooks in vaginas but also watching the growth of his own method. It is clear that he no longer sees a duality but rather the double nature of everything and everyone. In the pseudo-Buddhist fable Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring (2003), deliberately simplified for a less discerning audience and pretending to be a balanced story in the Japanese style, he begins to see infinity behind duality, much like a Möbius strip. This theme would then become central to one of his most internal, personal films. Entering 2004 with confidence, he won two directing awards at major festivals—Berlin and Venice—for what are truly two of his most impeccably elegant films.

South Korean director Kim Ki-duk poses during a photo session at the 69th Venice Film Festival on September 5, 2012 at Venice Lido/ TIZIANA FABI/AFP/GettyImages

Samaritan Girl (2004) is the perfect example of a movie that changes its protagonist after the first third, and with this change, everything else also changes. The principle is not new—after all, everyone remembers Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960)—but at the turn of the century, it became almost an idée fixe for filmmakers. However, no one has worked on this as meticulously as Kim, and the viewer most likely wouldn’t immediately notice how the yellowish, immorally innocent manga film about schoolgirls with dark red scarves, one of whom earns money for a trip to Europe by prostituting herself, turns into a dark, swampy tapestry of medieval moralizing in the second half. The movie can only be read as the wise old adage ‘Anything can happen in this world’, and every adult will surely see a transparent allegory of what happened to them and what they perceived as a universal law.

3-Iron, which won the prize for best director in Venice in September 2004, is a movie about a man who exists alongside the world of people, automatically repeating their actions without any reflection. He moves into the empty apartments of people on holiday, and for a few days, the people in the family pictures, their belongings, their records become his family, his stuff, his music. After being caught and imprisoned for this, he discovers and cultivates a new talent: shadowing people everywhere so that they do not notice his presence. This is what his life will be like after release, and it is certainly easy—unlike living your own life and making your own decisions. The only thing he does is mimic the gestures of others behind their backs, and that’s all he cares about. Kim shot the movie with an appropriate lightness. It is his best film, and one of the best in the world, because for 120 minutes, it gives us a taste of what a relief it is to be free of our own thoughts, actions, and words.

In the bright and happy sea fairy tale The Bow (2005), much like a freshly washed window on a sunny, summer morning, Kim cast the dorama-style cozy Seo Ji-seok in the lead role. For the first time in his career, the director made a boy who is free from the carnal determinism of any man the main character, thus giving him the highest, frankly fantastic (confirmed by the overly romantic entourage of this story), degree of freedom. Kim rightly felt that he had reached a high level of freedom, both creatively and internally, and that it was time to move on to the next level. The result, however, was a hodgepodge of films that, for all their brilliance in staging and performance, could have been made by perhaps François Ozon3

Kim’s work was a continuous stream of the popular festival trend of story-driven films without intellectual aspiration or pretensions like the films that the European masters were making in the 1970s. In the third in a series of these films, Dream (2008), Kim touched on a theme he could never really master—the correlation between dreams and reality. This was clearly the case of hitting a clam, and the director disappeared from public view for three years.

«Dream» (Kim Ki-duk, 2008)/Alamy

DISSOLUTION

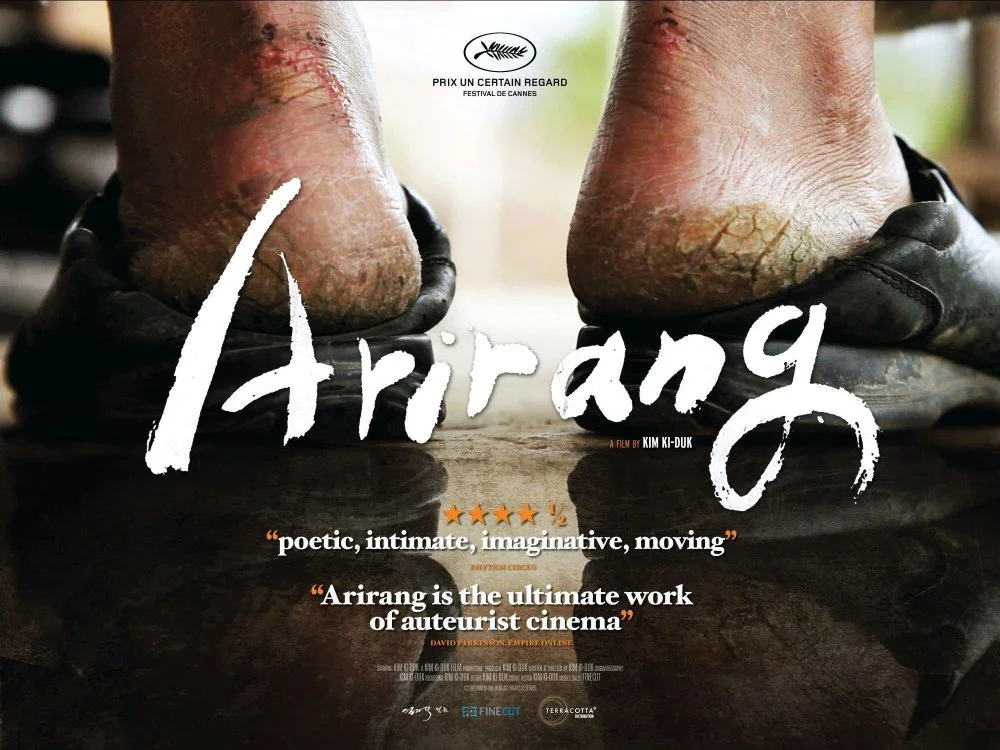

In May 2011, Kim Ki-duk resurfaced at the Cannes Film Festival: his sixteenth film, Arirang, shot on a cheap digital camera, was a report on how he had spent his fiftieth birthday in virtually a pigsty, in an unheated farmhouse, in the middle of which he set up a tent for warmth. He drank god knows how many bottles of soju (Korean rice vodka) for warmth, chasing it down with canned food and eating out of a dog bowl. Occasionally, he would break into a performance of the song in the title, about the hill he had spent his life climbing and descending. During the performance, bitter tears streamed down his swollen face—anyone over the age of fifty would understand this reaction.

«Arirang» (Kin Ki-duk, 2011) poster/Alamy

After sobbing profusely and inventing all sorts of excuses for his lack of international awards—those interested in the details of Kim’s life can hear directly from him in this film—he admitted that after fifteen years of making films, he would like to at least be the first Korean to win the top prize at a major international film festival. It was so childishly sincere and honest that in Cannes, where the film was shown as part of the Un Certain Regard program, he immediately won the main prize, and a year later in Venice, he was awarded the Golden Lion for Pietà.

Even if Pietà were to turn out to be nonsense, we should applaud both the jury—for what we heard—and Kim Ki-duk, for his genuine frustration in making Arirang and for making public what we show only to our closest circles if at all. In Pietà, he returned to the bad-boy image, tackling the slippery and, if we’re being truly honest, traumatic subject of mother-son relationships. His own experience with his mother’s serious illness was a major factor in Kim controlling his drinking and returning to normal social functioning. In his next film, Moebius, he opened this theme up even more deeply and radically, extending it to the whole system of how a bourgeois family functions. After performing an autopsy in the film, the character fails to sew up the incision, which did not please many people. In addition, women were unlikely to understand and relate to the extremely lucid story about what would happen if you cut off a man’s penis, and thus the rating of this film is low. In the role of a father whose cheating provokes his wife to cut off their son’s privates, and who then sacrifices his own privates for him, Kim went back to his first ‘bad boy’, Cho Jae-hyun, after an eleven-year hiatus. However, both men faced serious accusations during the #MeToo Movement for allegedly sexually harassing and assaulting actresses on set. Meanwhile, Kim had already begun to go down a more conventional path, for example, with The Net (2016), a film about mutual espionage between North and South Korea. While it is a well-crafted and impressive film, it could have been directed by a large number of people. The #MeToo Movement gave him the chance to fulfill a long-held dream he expressed in Arirang—to spend a year in each country where he was loved and make a movie in each one. After all, with the passing of his mother and nothing else to keep him in Korea, he was finally able to live this dream.

The countries in which he was beloved were to be found in the former expanse of the USSR. He was right in calling these places a cinematic virgin land: each country has its own truly unique architectural, planning, and behavioral space, and, if I may be honest, no one but Kira Muratova has created a consistent and recognizable chronicle of our current (post-1991) life since the collapse of the Soviet Union, though there have been some good films.

The first thing Kim did was go to Kazakhstan: Almaty made a big impression on him when he was filming in the city in 2011. That’s also when he met Dinara Zhumagaliyeva, an actress who volunteered to be his producer. On this visit, he must already have been impressed by the view of the Medeu Ice Rink from the path leading to the ski resorts, a view which is exactly like the iconic shot from Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring in which Kim himself drags a Buddha statue to the top of the mountain and looks down on the saucer of the lake on which his pagoda is floating. However, he refrained from introducing this motif into his Kazakh film Dissolve (2019) because it would have given the picture an unnecessarily bucolic flavor.

«Dissolve» (2019)/From open sources

Instead, it was as if he withdrew from what was going on—both the semi-amateurish filming with dirty, unfiltered live sound and Zhumagaliyeva’s frankly amateurish performance as ‘La fille aux Camélias’. This is surprising because in her other well-known screen persona—a schoolgirl tormented by her mother and brother, who must call them every hour and be home in time for dinner—she is as alive and vital as a breath. The actor’s dual nature only served the film’s theme of duality and corresponded to the image of Almaty as it appears not to a tourist but to an outsider who has settled there for a while. The idea and even some of the plot twists are borrowed from the 1972 Bollywood hit Seeta Aur Geeta, which was so popular in the USSR in general and in Kazakhstan in particular that its plot has long since entered our mythology as a folk tale. The thick, lush hair of Sanjar Madi, an actor with the confident, commanding type of masculine beauty and on-camera demeanor that landed him on the cover of the local Men’s Health magazine, is in this film combed into a slanted parting. This hairdo, his flowered shirt or ski cap worn over an expensive overcoat, and the gallantry of a wealthy gentleman make him resemble Vinod Khanna, the Indian film idol of the 1970s. In the cable car scenes, however, the texture of the film and camera take on a contradictory life of their own. The damp feeling of a winter’s day at the Shymbulak Ski Resort, combined with the damp feel of the amateur filming, makes the ascent to the cabin and the hot sex in the wood-paneled room of the chateau palpable on an almost tangible, real level. This is the pinnacle of cinematography, when the viewer says: ‘The movie is just like real life’ or ‘It’s about me’. This is not the first time Kim Ki-duk has achieved this effect, showcasing his innate talent of a born filmmaker. He skilfully uses elements that make the viewer feel uncomfortable and awkward, gradually building them up in the film until they suddenly seem to open the door to the fourth dimension where everything falls into place. This technique is similar to the sexual acts—Kim, of course, was a bold man and a daring filmmaker.

Dissolve was the last movie he was able to finish. The footage for his next film, Call of God (2022), shot in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, was edited after his death by Estonian producer Arthur Weber. Estonia was set to continue the anthology of Kim’s post-Soviet works. But even in this work, it is clear how creatively the director approached its texture. Bishkek is shot completely differently from Almaty. The black-and-white photography Kim uses here reveals its charm. Together with the elegant mini-dresses worn by actress Zhanel Sergazhina, it evokes the zeitgeist of the 1960s and 1970s, a time of unprecedented growth in Kyrgyz cinema, urban renewal, and women’s fashion.

Director Kim Ki-Duk portrait session, Director of the «Arirang» film, he obtains the award «Un Certain Regard» during the 64th Annual Cannes Film Festival on May 18, 2011 in Cannes, France/ Laurent Koeffel/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

Like many of Kim’s characters (Time, Dream), the young heroes of Call of God muffle their budding love with jealousy and a constant need for proof that they are loved. The version Weber presented in Venice is prefaced by Kim’s words as an epigraph: ‘As one grows older, one is more and more often reminded of one’s youth. Today, I would correct many things that took place in my youth, and yet it was beautiful.’ In the movie, the female lead is awakened several times by a phone call in which a man leaves a message: ‘The dream you saw will happen again in reality.’ In the finale, she wakes up to a movie in color and a colorful morning, goes out in the same minidress, and meets the same young man under the same circumstances. Abylai Maratov, who played the young man, said in an interview in Venice: ‘Since she saw in the dream how not to behave in love and suffered from it, she will take the lessons of the dream into account in life, and everything will be fine with them.’

With his final film, Kim Ki-duk gave the female lead a chance to wake up from the quagmire of sleep and the movie he had made for her. Soon after completing this work, he passed away, with some obituaries suggesting that he passed to his eternal rest. The film, which unintentionally became his final testament, gives us hope, bringing to mind the last words of Cleopatra in the famous film of the same name, when she puts her hand into a jar of poisonous snakes: ‘How strangely awake I feel. As if living had been just a long dream. Someone else’s dream. But then now will begin a dream of my own.’

South Korean director Kim Ki-duk poses during a photo session at the 69th Venice Film Festival on September 5, 2012 at Venice Lido/ Tiziana Fabi/AFP/GettyImages

Movies that say everything about Kim Ki-duk:

As a director: 3-Iron (2004) won the Silver Lion at the Venice International Film Festival and is a short and evocative film about people who live as shadows—literally, not figuratively—and are, therefore, happy. In addition, Samaritan Girl (2004) won the Silver Bear in Berlin. This film explores the harmony between the form and content amidst semantic and emotional shifts, when the protagonist’s role passes from one character to another. The subject of the film is underage prostitutes.

«Samaritan Girl» (2004)/Alamy

As a thinker: Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring (2003) is Kim Ki-duk’s most popular movie with the general public. Think of it as the director thumbing his nose behind your back. Kim made his only appearance as an actor in this film, somewhat souring the Buddhist parable about a monk and his misguided disciple with a grimace of narcissism—for example, in the training scenes, he flaunts his advantageously impressive physique. Additionally, Pietà (2012), which won the Golden Lion in Venice, juggles various aspects of Christian dogma and occasionally lapses into incest.

As a citizen: The Coast Guard (2002) is about a maritime border patrol whose actions only hurt their own (two died, two went insane) and which ends ‘with a prayer for a future unified Korea’. The Net (2016) is about a North Korean fisherman and a South Korean state security officer, who, after going through terrible ordeals and enduring pettiness from both sides, set each other up for a date in a unified Korea.

«The Coast Guard» (2002)/Alamy

As a man: Bad Guy (2001) is a film about a really bad character who, intriguingly enough, only wants to sleep cuddled up.

As a person: Arirang (2011), which won the Prix Un Certain Regard at the Cannes International Film Festival, is like a ninety-minute interview Kim conducted with himself at the end of a three-year period of crisis, downtime, and, as he presented it in the film, a drunken binge in a pigsty-like environment. Also notable is Address Unknown (2001), in which the stories of Ki-duk’s childhood in the early 1970s are structurally intertwined like a dorama or TV series, making the film a great treat for a relaxing evening on the couch.

As a provocateur: The Isle (2000) is a film of pure beauty and is the perfect conversation starter over drinks about its impact on viewers. In contrast, Moebius (2013) is a film that delves into pure, unsettling truths and is hardly suitable for conversation that’s meant to make you look smart. However, only men will understand this fear, and they will not only not talk about it but will also try not to think about it.

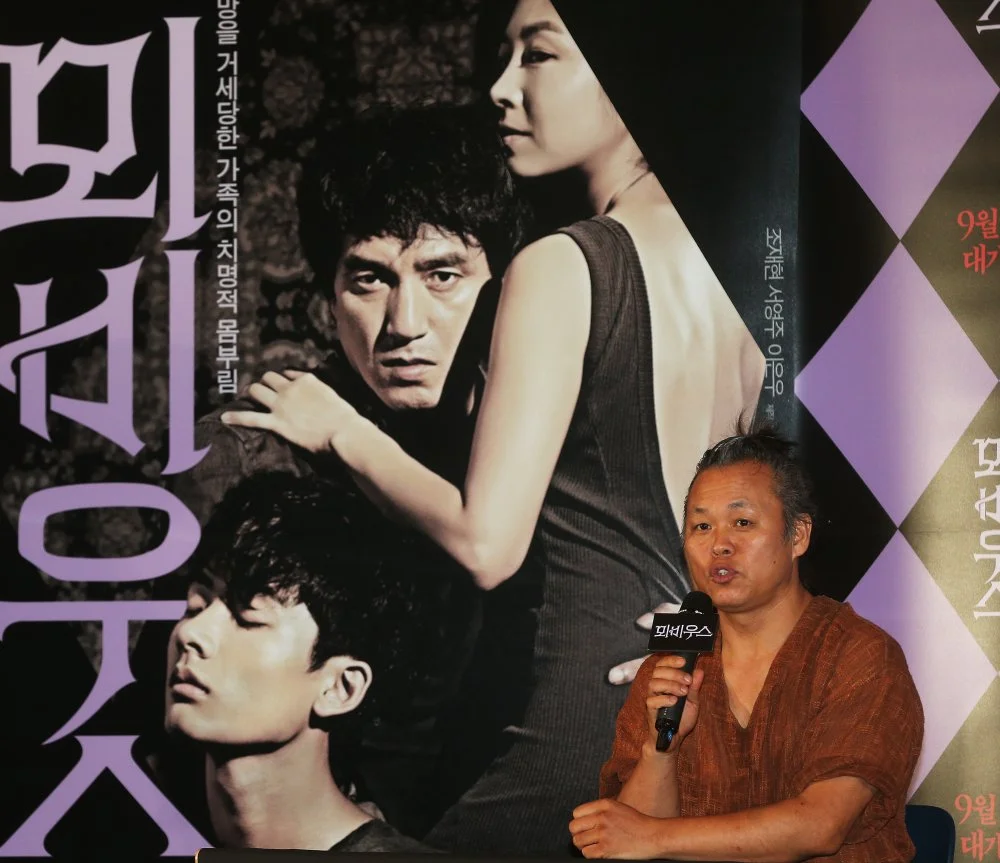

South Korean Director Kim Ki-Duk Responds To Reporters' Questions During A Publicity Event For The New Movie «Moebius» In Seoul On Aug. 30, 2013. The Movie Will Appear On South Korean Screens Starting On Sept. 5.2013/Legion-Media