In an in-depth interview with Qalam, historian Akhmet Toktabay discussed a wide range of topics related to horses, including rituals preserved since the time of the Saka, horse ownership and breeding, how many horses Kazakhs typically had, the origin of the word ‘horse’, and much more.

Forged by the Steppe: The Kazakh Horse

The history of the Kazakh horse begins with the Botaii

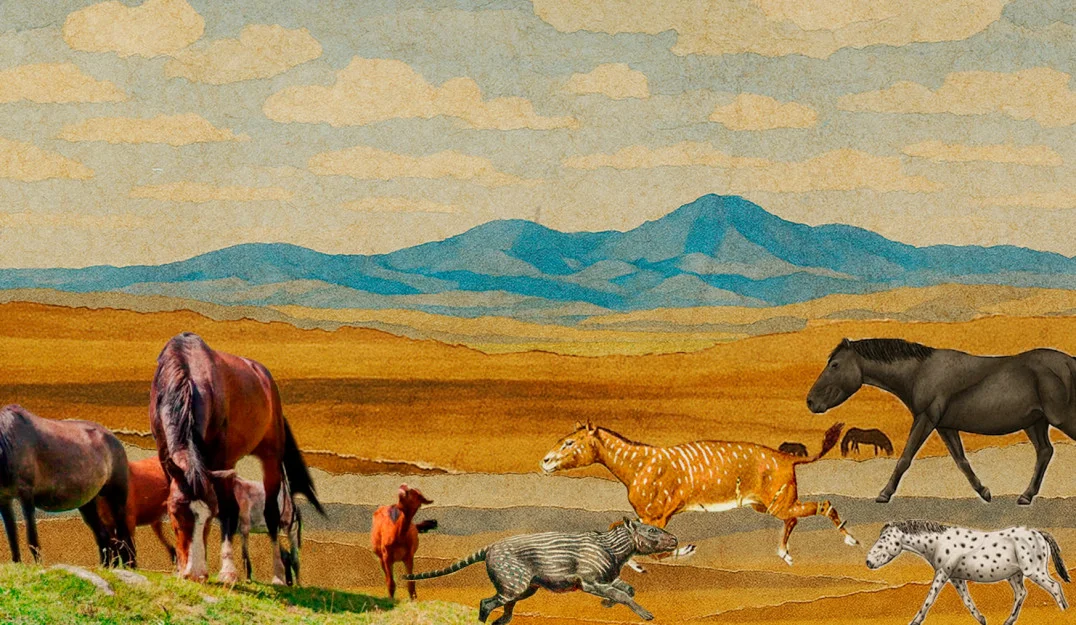

The Jaby is a traditional Kazakh horse type known for its compact build, rugged appearance, and thick mane and tail. It’s a hardy, self-sufficient breed that gains weight quickly and remains common across the steppe to this day.

The Botai culture horse remains, reconstruction, 4-3 millenium B.C. North Kazakhstan, Botai culture. Cultural centre of Turkistan, Kazakhstan/Alamy

Unlike other breeds, it doesn't need to be stabled, fed, or watered regularly. It can find food on its own in the steppe and withstand extreme temperatures, from +40°C to -40°C. A Jaby can cover distances of 200 to 300 kilometers in a single day.

It was on Jaby horses that the Russian army conquered Central Asia. Russian officers wrote extensively about this breed, and the journal Horse Breeding and Hunting, published from 1841 to 1918, often featured detailed accounts of the Kazakh horse. Some issues ran up to 1,000 pages and contained a wealth of information on horse types, breeding practices, and the distinctive qualities of the Jaby.

Akhmet Toktabay / Qalam

Horses Buried with Their Riders

Archaeological research in Kazakhstan has revealed that in ancient times, people were often buried with their horses, a practice dating back to the Saka period. It was believed that life continued after death, and the deceased would need a horse to ride in the afterlife. These burials weren’t just symbolic; the horse was buried along with full riding gear, carefully placed beside the body.

In the Arjan burial mound in Tuvai

Decorated funerary horse from Berel curgan. 4th century BCE / Wikimedia Commons

Such religious beliefs also appear, though more rarely, during the Turkic era. Even when horses were killed, it was not on the same scale as among the Saka as only one or two were usually buried along with the deceased.

The Ritual of At Tūldau

Among Kazakhs, if someone asks, ‘Is your father well? How is he doing?’, the response might be ‘We placed our father on a horse and sent him off.’ Everyone immediately understands this to mean that the responder’s father has passed away.

In the Kazakh tradition, on the anniversary of a person’s death, a horse is slaughtered in their honor. This is where the concept of tūldağan at, or the horse of mourning, comes from: after someone dies, a specific horse is chosen, its mane and tail are cut, and it is released into the wild. It is then left untouched for an entire year—no one, not even thieves, rides or steals it. After a year, the horse is sacrificed at a memorial feast called as, and its skull is then left at the grave.

Kazakh Funeral Repast on the 40th Day / Library of Congress

All of this is a modern version of the ancient Saka ritual of burying the dead with a horse. This tradition, which honored the bond between humans and horses, has evolved into what the Kazakhs now call the as, a memorial feast to commemorate the dead. Dating back around 2,500 years, its roots can be traced to the Vedic ritual of ashvamedhai

Horse Owners and Horse Breeding

Among the Kazakhs, there were wealthy individuals who owned thousands of horses, especially in Central Kazakhstan. The names of some of these wealthy men along with the sizes of their herds are still known. For example, the famous bais (noblemen) Aldan and Jūman owned 24,000 horses. The Aqtailaq bai from Qorgaljyn, a village in the Akmola region of Kazakhstan, had 17,000 horses. Other bais such as Aznabai and Sapak each kept herds of 12,000 horses. Tan Myrza, a wealthy man from East Kazakhstan, had 10,000 horses. Many horse owners also lived in the Orenburg and Oral regions, as well as among the Jağalbaily clan.

Such large herds required vast pastures, which were allocated and regulated by the bis, who were judges of customary law. For example, if one man had 2,000–3,000 horses but a jut (a harsh winter leading to mass livestock deaths due to a lack of pasture) struck and his livestock perished, while another Kazakh prospered and his herds grew, the land of the first would be transferred to the second. In other words, the more livestock one had, the more land they were entitled to.

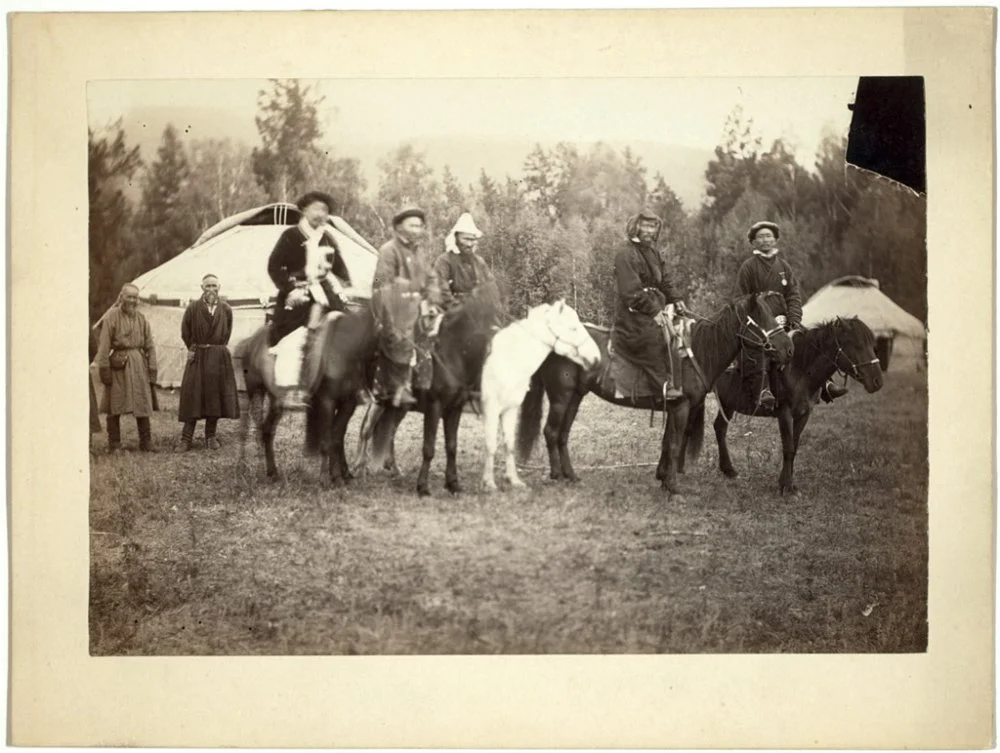

Kazakh horsemen. North Kazakhstan, 1885–1886 / Library of Congress

Wealthy men provided food for the entire clan. For example, the bai Aqtailaq slaughtered sixty horses in the winter, not for himself, but for his kin and the poor. In addition, the wealthy supplied horses to the army. The Turkologist Vasily Radlov wrote:

‘Nomadic Kazakh society, though it may appear chaotic from the outside, is, in fact, well-organized. Everything is governed by customs and the laws of the bis.’

In addition, participants of Russian expeditions who traveled across Kazakh lands in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries recorded:

These people always slaughter a horse for the winter. They drink a lot of kumis. Their warhorse is kept separately.

These sources also note that Kazakhs do not eat beef. It is stated plainly: ‘Beef is the food of the poor.’

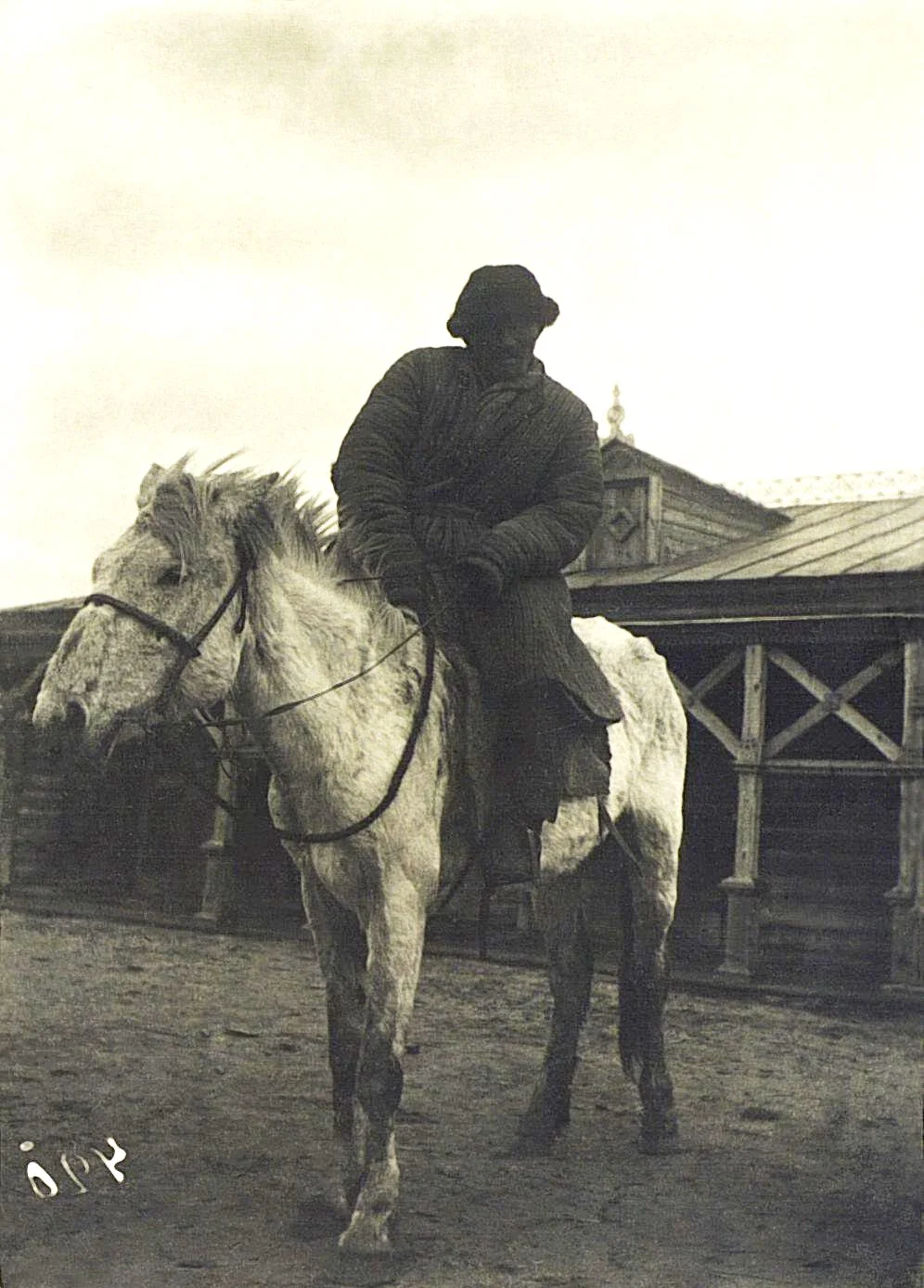

Samuil Dudin. From the album «Kazakhs of the Semipalatink Region». 1899 / romanovempire.org

The status of the jylqyshy, or the horse herder, deserves special attention. He was held in higher esteem than, for example, sheep herders or other people who looked after animals. He was even given a seat at the table to the right of the horse owner. Caring for horses, of course, was no easy task. During blizzards in the winter, the herder would stay in the saddle for days, moving nonstop with the herd, which is why horse herders were usually considered heroes. Indeed, there have been many cases where a wealthy bai gave his daughter in marriage to a horse herder who saved his herd from a jut.

The Kazakh Horse Trade and the Origin of the Word ‘Horse’

During the eighteenth century, both the Russian Empire and China needed horses, especially for their armies. For example, during Peter I’s Azov campaigns against the Ottoman Empire in 1702–03, his army lacked horses, and people had to pull the cannons themselves. In this context, Kazakhs became key suppliers, selling horses to both sides, and it was during this time that the saying emerged: ‘The Kazakh steppe is an inexhaustible source of horses.’

Recognizing the importance of this trade, the Chinese opened many livestock markets in Urumqi and Chuguchaki

‘Provide the Kazakhs with the best goods. Be it tea or silk—give them whatever they ask for. Do not deceive them.’

Because both empires were in dire need of horses, the horse trade became a strategic priority. On the Chinese side, it was entrusted to a famous general named Li. On the Kazakh side, Ablai Khan dispatched his trusted envoy Kabanbai, who delivered the first 300 horses to Qing markets. The Menovoy Dvor (trade court) in Orenburg became a hub where thousands of Kazakh horses changed hands annually.

Horse trading among the Kazakhs dates back to the ninth and tenth centuries, when ties with Russian principalities were already well established. At the time, the Kazakhs were known as ‘Alash’, and the horses that came from their lands were called ‘Alash at’ (‘the Alash horse’). According to the renowned Russian scholar Vladimir Dal, the Russian word loshad (meaning ‘horse’) actually comes from this term. This etymology was later supported by the respected philologist Oleg Trubachyov, underscoring the deep historical influence of Kazakh horse culture on the region.

How Many Horses Did the Kazakhs Have?

According to statistics from imperial Russia, there were over 4 million horses in Kazakhstan alone. If we include the livestock of the Kazakhs in Mongolia and China, the number was as high as 7 million. The height of the Kazakh people’s prosperity came in 1913, with both the population and livestock numbers on the rise. At that time, the Kazakhs owned 49 million head of livestock. Of these, 5 million were horses, 1.2 million were camels, and the rest were cows, sheep, and goats.

Horse herder near Aralsk, Aral Sea, Kazakhstan / Alamy

At that time, the Kazakh herds had grown so large that wealthy Kazakhs rented land from Cossacks in Siberia, Orenburg, and Astrakhan to use as pastures and wintering grounds.

But Tsarist Russia was not kind to the Kazakhs. Along both sides of rivers like the Yaik (Ural) and the Irtysh, a stretch of 10 verstsi

How the Soviet Union Decimated Kazakh Livestock

All of this prosperity, however, was wiped out by the Soviet regime. We only need to look at the numbers to know. According to the 1939 census in the USSR, only 5 million head of livestock remained of the original 49 million in 1913. Of those, only 300,000 were horses. At that time, campaigns were carried out to cull horses and reduce their populations. One reason was the internal demand for meat in Russia, but another, more insidious, was ideological, which was the fear that as long as a Kazakh remained in the saddle, he would not give up his warrior spirit. And that’s why livestock was destroyed on a massive scale—horses were gunned down with machine guns.

This dark history lives on in the names of places in Kazakhstan: Jylqy qyrylğan in Jetisu, meaning ‘Where the horses were exterminated’, and At atqan in Semey, meaning ‘Where the horses were shot’. These places are permanent memorials to this equicide, physical markers of a deliberate campaign to break the backbone of Kazakh nomadic identity.

This discussion with Akhmet Toktabay is only a glimpse into the ancient and profound legacy of the Kazakh horse. You can watch the full interview on our YouTube channel Qalam Tarih.