Historically, capturing women was one of the main goals of military campaigns. Among sedentary peoples, violence against captives was common; the same, it seems, cannot be said about the people of the steppes.

There is an episode in Abdijamil Nurpeisov’s novel Blood and Sweat, a classic of Soviet Kazakh literature, describing an attack by Turkmen Alamans on a Kazakh fishing village in the Aral Sea region in 1917. After killing the men who put up resistance, the Turkmen return to their homes across the Ustyurt Plateau with their captives and livestock:

A shot from the movie "Blood and Sweat"/From sources

As soon as they left Bel-Aran and cooled off from the killings and robberies, the Turkmen began to court beautiful women and girls. According to Turkmen marching custom, a Turkmen warrior should not seize a woman by force. The captive must choose her own warrior to sleep with. The women did not look at the Turkmen. Covering their heads with chapans [coats], they howled monotonously on their horses, lamenting the death of their loved ones and their captivity. Only Baljan rode without covering her face, she did not tremble with grief, but looked at the Turkmen, choosing a husband for herself. And when the Turkmen asked her to choose, she immediately pointed to the wiry, dark-skinned murderer of her husband.

‘That one, on a blue dun Argamak horse.’

That wiry man was the Turkmen kurbashi* [*A leader of armed brigades in Central Asia, which fought against Soviet rule]. His name was Ataniyaz. When he learned of Balzhan’s choice, Ataniyaz smiled smugly. But he did not care about Balzhan at the moment. He wanted to win over Aigansha.

Aigansha was silent, turning away stubbornly. At one point, he rode up close to her, stirrup to stirrup, and grabbed the reins of her horse. He thought she was frightened by his wild appearance and wanted to show her that he could be cheerful too. When he turned Aygansha to face him, he suddenly grinned, blinding her with the whiteness of his tightly set teeth. His teeth gleamed blue, but his sweaty, dark face was still beastly cold.

‘Give in or I’ll make you!’ he said and, leaving her, drove forward.

Afraid that Aigansha would run away, he ordered the Turkmen to lie down around the fire near which she was sitting. Aygansha lay on the bare ground with her palms under her head. She knew that tonight was a crucial night. Tomorrow, the Turkmen would enter the land of Kara-Kalpakstan, and from there it was too far a journey home—there would be no escape.

Mayne Reid. The turcomans. 1861/Wikimedia Common

The Prisoner Chooses Her Own Husband?

When I first read the novel as a young person, this scene caught my interest at once. In the past, even in ‘civilized’ nations, widespread violence against the women of the defeated enemy was a common practice, but this novel is about Turkmen and Kazakhs, whose centuries-long history of confrontation and conflict has led to very strict customs being put in place. How, then, should we understand the Alamans’ restrained attitude toward captured women? Is it because the story is romantic? But Blood and Sweat was in line with Soviet ideology, and it shows how the Kazakh poor learn about the Russian proletariat. Its purpose was to prove that the life of the Kazakhs had been hopeless and cruel for many centuries and that only Soviet rule gave it any real meaning. The episode of the Turkmen raid is, for the most, quite accidental to the plot of the novel—the Turkmen appear only in this episode and are portrayed without any sympathy. The custom of not touching the captured women during the raid is reported as a matter of course. However, in reality, the capture of girls and young women was one of the main goals of the raids.

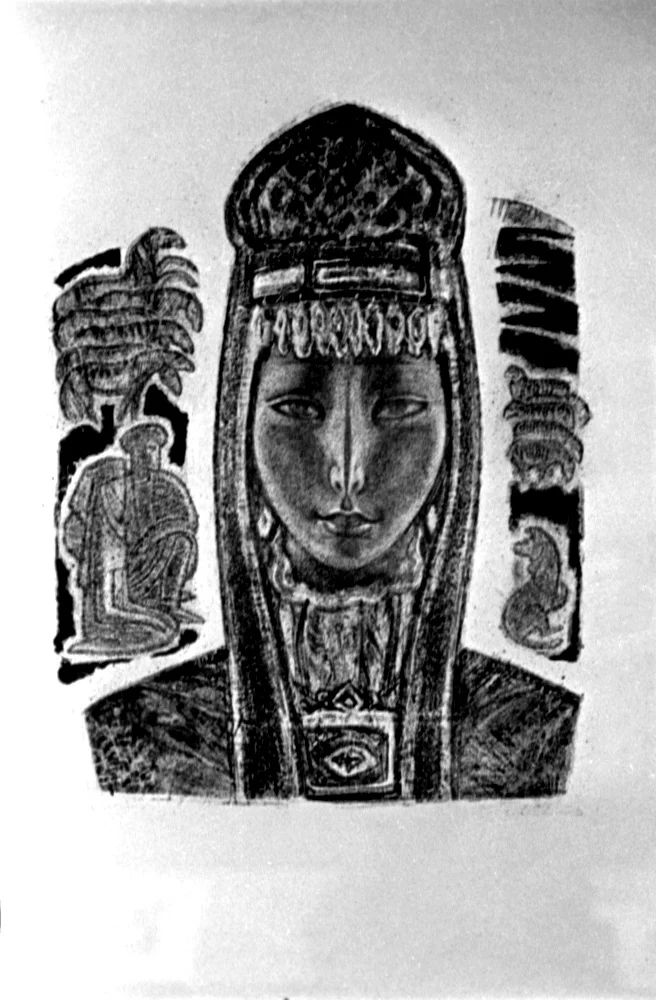

E. M. Sidorkin. Beauty. 1966/RIA

A few years ago, during an expedition to Mangystau, local historians pointed out the guard mountains (qarauyl töbe), where signal lights were lit in case of an enemy invasion. They also showed the secret paths used by girls and young women to escape on horseback from the Mangystau lowlands to the Ustyurt Plateau to avoid capture by the enemy, the main task for everyone. A Kazakh man, even if he was alone against a whole detachment of Turkmen Alamans, would fight to buy time for the women. In the same way, he would fight to delay the Turkmen who had captured the girls and not let them go to their territory until reinforcements arrived. For example, in 1856, in the Karagan-Bosaga region, sixty Kazakhs led by Batyr Baluaniyaz caught up with the Khivinians, who outnumbered them three to one, and gave them a fight to rescue the captives. The Khivinians put up a fierce resistance, and the Adais faltered and began to retreat. Baluaniyaz, hearing the screams and cries of the Kazakh women, wept (remember that Kazakh batyrs wept in epics and it was not considered shameful) and ordered Aqyn Qalniyaz to sing to remind the warriors of the women waiting for their help. The Kazakhs won and freed the prisoners, but Baluaniyaz himself, his brother, and many warriors died. And this is just one of many such stories.

Sherkala mount. Mangystau./Wikimedia Commons

When I asked Murat Akmyrzaev, a local historian from Mangystau, about the truth of the episode of captured women in Blood and Sweat, he confirmed that such a rule existed and was unconditionally followed. The relatives of a captured girl or woman had a chance to fight for her and bring her back unharmed, and the Kazakhs’ attitude toward captured girls was the same.

This rule of war seems to have existed not only in western Kazakhstan but also on other frontiers, such as with the Dzungars. Saken Seyfullin, the renowned Kazakh poet, wrote a poem inspired by a local legend. The poem, titled ‘Okjetpes’ (meaning ‘an arrow will not reach'), is about a rock of the same name in Kokshetau. During Ablai Khan’s time, a beautiful seventeen-year-old Kalmyk girl was captured by the Kazakhs; the batyrs fought over her, and Ablai let the girl choose her own husband. She tied her handkerchief to the top of a rock and promised to marry the warrior whose arrow pierced the handkerchief. It can also be seen in Mağjan Jumabayev’s poem ‘Bayan Batyr’, which is about the same period of Kazakh history. A batyr warrior brought home a beautiful Kalmyk girl from a campaign, but she rejected him, while the batyr’s younger brother Noyan fell in love with the captive and ran away with her.

View of Burabay lake with Okjetpes and Jumbaqtas rocks/Alamy

Perhaps these are simply beautiful legends, but a legend or an epic passed down by word of mouth for many centuries is prone to be adapted. The storyteller accounts for the perceptions of their audience and tells the ancient story in a way that convinces them. Exaggeration and fiction are acceptable, but motivation and logic must match the mentality. This is roughly how Hollywood works: the stunts in a blockbuster are unbelievable, but the hero’s decisions and way of thinking must be believable to the audience, or the movie will not become popular. Thus, the plot about a captive woman who chooses her own husband was understandable and close to the Kazakhs of that ethnographic period.

Do Not Be Hasty in Your Envy

I am far from trying to prove that the fate of the captives was in their hands. If the captive did not make her choice during the campaign, once in their territory, the Alamans decided to whom she would be given or if she would perhaps be sold into slavery. She might become a küñ (slave) or a qūma (concubine). Or, if she had borne children, she might be a younger wife, especially if the older wife was childless. It is said that Batyr Bogenbai of the Qanjyğaly family often went alone on raids against the Dzungars, bringing back wagons of captives, whom he then gave away. It is also said that in Bogenbai’s time, there was not a single Qanjyğaly without a toqal (unofficial wife). For a poor man who could not pay the qalyñ (dowry), a captive could be his only wife. In any case, the slavery of captives among the steppe peoples was milder than the classical slavery of the sedentary peoples. A slave and a slave girl could marry of their own free will, earn respect, and join the clan (the Kazakh word qūl does not fully correspond to the concept of slave as it falls somewhere between a slave and a servant), and their children were considered free in any case.

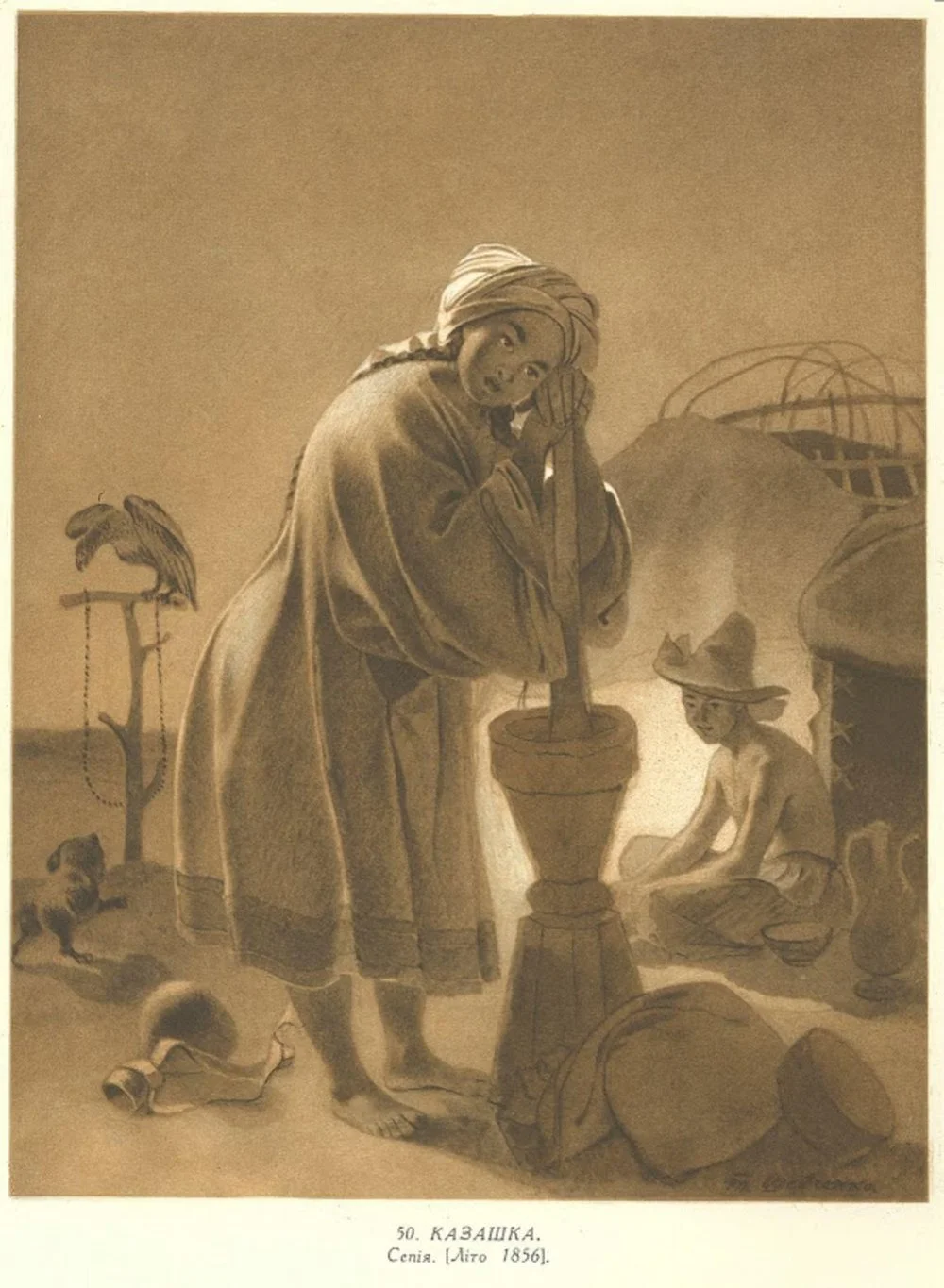

Vasily Vereshchagin. Kazakh Woman. 1867/Alamy

The fate of the captive could be decided by the one who captured her, or the leader of the detachment, or the khan, etc. In the legend of Atymtai Jomart, the ancestor of the Adai Jemenei family, it is said that the khan, in gratitude for Atymtai providing food and water to the whole army during the campaign, offered him a reward of his choice. Atymtai asked for a white argamak (horse), which no one had ever ridden, new armor, and weapons, as well as for the prisoner Aqsūqsyr to be given to him untouched.

In epic texts, one can see different collisions related to captives. A girl from the enemy’s camp, even if she came to the batyr of her own free will and helped him defeat her father and brothers, is perceived as olja (prey).

The steppe peoples also honored the custom of sauğa, in which any person could approach a hunter or warrior and ask him for something valuable from his booty. A sauğa could also be a request for mercy—the defeated enemy could ask the victor for his own life and freedom as a gift. There are steppe legends in which a woman from a defeated nation may have asked for the life of her father or fiancé, her ancestral armor, the best horse, et cetera, as a sauġa. According to the steppe warrior code, the victor must grant this request (for more details, see Serikbol Qondybai’s The Book of Warrior Spirit).

In the epic Qoblandy, Batyr Karaman, the protagonist’s companion, asks for Karlyga, the enemy khan’s daughter, to be his sauġa. Karlyga, who loves Qoblandy and betrayed her father to help him escape from captivity, is given to Karaman by Qoblandy. In many versions of the epic, Karlyga continues to fight on Qoblandy’s side. In one of her campaigns, she captures Qanykei and Tynykei, the sisters (and in other versions the daughters) of the enemy khan Alshagyr. Karaman asks her for the prisoners as part of the sauğa. Karlyga reminds him that she herself belongs to Karaman as a trophy and cannot give away her booty. Karaman agrees to release her and takes the two girls in exchange. This motif is also found in other versions of the epic: Karlyga gains her freedom by giving up the daughters of the khan she has captured (Babalar sözі (The Words of Our Ancestors), Vol. 36).i

Karlyga, Tynekey and Kunekey/Dall-e

And yet, the girl brought back from the campaign is considered a trophy. In S. Dilmanov’s version of the Qoblandy epic, a batyr breaks through a long-closed passage in the Tezkentau Mountain to the land of Alyp Khan because of his love for Alyp’s daughter Ilia. He saw Ilia in a dream, fell in love with her, and promised to find her (this version is a synthesis of heroic epic, oriental love tales, and magic tales). With great difficulties, Qoblandy and his companions reached the city of Alypa, and Ilia and her brother help Qoblandy to defeat his father (Babalar sözі, Vol. 37). After their victory, out of courtesy, Qoblandy offers Ilia to his older companion.

Even Kortka, the daughter of the high-born Khan Koktim-Aimak (in more archaic versions of the epic, she is the daughter of the old witch Köklen or Kökten), whom Qoblandy received along with a rich dowry after winning the contest for her hand in marriage, is to some extent a trophy. Qoblandy says to his younger sister: ‘Qalyñsyz da, kädesiz, alyp keldim bir jeñge’ (I brought you a jeñge [sister-in-law], having received her without any qalyñ and gifts.’). In a traditional society, for a wife to have status, it is important that the marriage is formally arranged with proper customs being followed. A proverb emphasizes this: ‘Qalyñsyz qyz bolsa da, kädesiz küieu bolmaidy’ (‘The bride may be taken without qalyñ, but the custom of the groom’s giving gifts [to the bride’s relatives] cannot be avoided.’).

Taras Shevchenko. Kazakh woman. 1856/Alamy

Perhaps because Kortka was given to Qoblandy without matchmaking, her word means less to her husband than the word of his younger sister, which is emphasized in Nurpeis Bayganin’s version (Babalar sözі, Vol. 36). Interestingly, this is the only epic in which the batyr (in the first part of the epic, before the captivity) behaves intimidatingly toward his wise and faithful wife in one episode.

The sisters Qanykei and Tynykei are depicted in the epic Qoblandy only as objects of exchange. After Koblandy’s capture, Karlyga’s younger brother Birshimbay goes to Alshagyr with good news. He receives the younger sisters of the Kalmyk khan as a gift for good tidings (süiіnshі), Alshagyr’s mother tries to get them out of the besieged city, and Karlyga kidnaps them and exchanges them with Karaman for her freedom. The names of these two women characters, in different spellings (Qanykei or Künikei, Tynykei or Tünikei), are usually mentioned together, and they are almost always passive—they are captured, they are pursued, and they are released from captivity.

Even in the fairy tale ‘Künikei, the Girl Who Lives under the Sun’, Künikei does not play a role, she is only a distant goal of the hero’s wanderings. In the heroic tale ‘Jelkildek’ (Babalar sözі, Vol. 75), two daughters of the khan are also taken captive. For the younger brother of the khan, rescuing his nieces from captivity is more important than the death of his brother and nephew, and he searches for a hero capable of freeing the girls and avenging the dead. There are stable word combinations in the story such as: ‘My beautiful Künikei, my noble Tynykei’ (Künikeidei köriktim, Tynykeidej tektim) and ‘Vengeful girl Künikei, noble girl Tynykei’ (Künikeidei kekti qyz, Tynykeidei tekti qyz). Qondybai considers these women astral figures, possibly personifications of the morning and evening Sholpan (Venus), noting the possibility of another meaning connected with the roots qan (blood) and tyn (breath), kün (sun, day) and tün (night). According to Qondybai in his book Mythology of the Pre-Kazakhs, from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, ‘... Künikei and Tynykei completely lost their mythological character and turned into minor folklore characters, simply filling up empty spaces.’

A shot from the movie "Blood and Sweat"/From sources

Is a Captured Woman Guilty of Giving Herself to the Enemy?

In traditional culture, a girl or a woman was not blamed if she fell into the hands of the enemy—that responsibility fell on the man. In several versions of the epic, after going through various vicissitudes of fortune, conquest, captivity, and subsequent release, Koblandy learns that his homeland has been conquered by the enemy and that his family has been taken prisoner. After arriving at the enemy’s headquarters, he meets his wife, Kortka, a prisoner of the enemy khan, in the steppe. Kortka saw her husband from the fortress wall and asked him to collect some kizyak (pressed dung used as fuel) in the steppe. Wanting to test her husband, she puts a bag of kizyak under her robe and tells Qoblandy that she became pregnant in captivity. The batyr then admits, though with obvious pain, that Kortka isn’t to blame for her capture. He is willing to raise even a thousand of her sons from the enemy because he experienced a great deal of loneliness and betrayal in his last campaign and has changed greatly. However, when he learns that it is only a prank, he laughs with great relief.

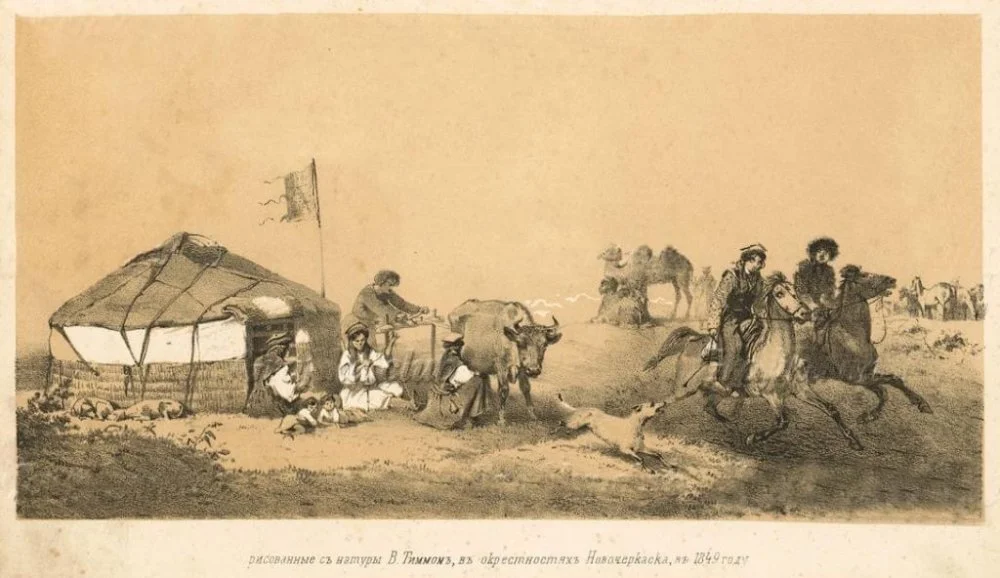

V. Timm. Kalmyks. 1849/Wikimedia Commons

This episode brings to mind the story of Chinggis Khan and his senior wife, Börte, who, according to one version, conceived their son Jochi in captivity. The Great Khan always recognized Börte’s son as his firstborn. In an article titled ‘Tattimbet’s East Turkestan Journey and the History of His Two Küis’, the researcher Talasbek Asemkulov quotes the legend of the Qylañ Batyr küi written by the eighteenth-century composer Baijigit. The title of the küi translates as ‘Pale-Faced Warrior’ or ‘Light-Faced Warrior’. According to legend, Qylañ Batyr’s face would glow as he marched on his enemies at night. The Kalmyk khan Surshan crushed the Kazakh auls (villages) in the lower reaches of the Aiagöz, and four Kazakh batyrs, led by Qylañ Batyr, gave chase. However, enemies surrounded the four brave men, and an unequal battle, in which all four perished, ensued. The batyr had a son called Meruert, and his maternal uncle Qosaidar Bey, who constantly reminded him about his father’s fate, raised him. And so, once he reached adulthood, Meruert put on his father’s armor, picked up his weapons, and went to seek vengeance on the Kalmyks. The tale has an amazing ending. Meruert fought Surshan and defeated him. He did not kill him, however, but pressed his blade against the khan’s throat and forced him to promise his daughter in marriage. Meruert returns to his homeland a married man, but this does not mean that the enemies are reconciled or that love has triumphed. Talasbek Asemkulov wrote of the küi: ‘The mother, or woman in general, is the progenitor, the essence of the people ... Instead of killing Surshan Khan, Meruert takes away his daughter ... We can say that together with Surshan’s daughter, Meruert took away all the countless generations of people embedded in her womb, that is, he took away the whole nation. If he had killed a single warrior, he would have killed him alone. As it was, he avenged his father’s death with a terrible vengeance.’ In this article written in the early 1980s, Asemkulov expresses a traditional view of the subject. Surprisingly, though, modern science says that a girl’s embryo already has eggs that will mature during her lifetime. Thus, a pregnant woman carries not only her daughter, but also the grandchildren of her daughter’s line. It is as if the steppe dwellers knew this when they regarded girls and young women as the most valuable trophy.

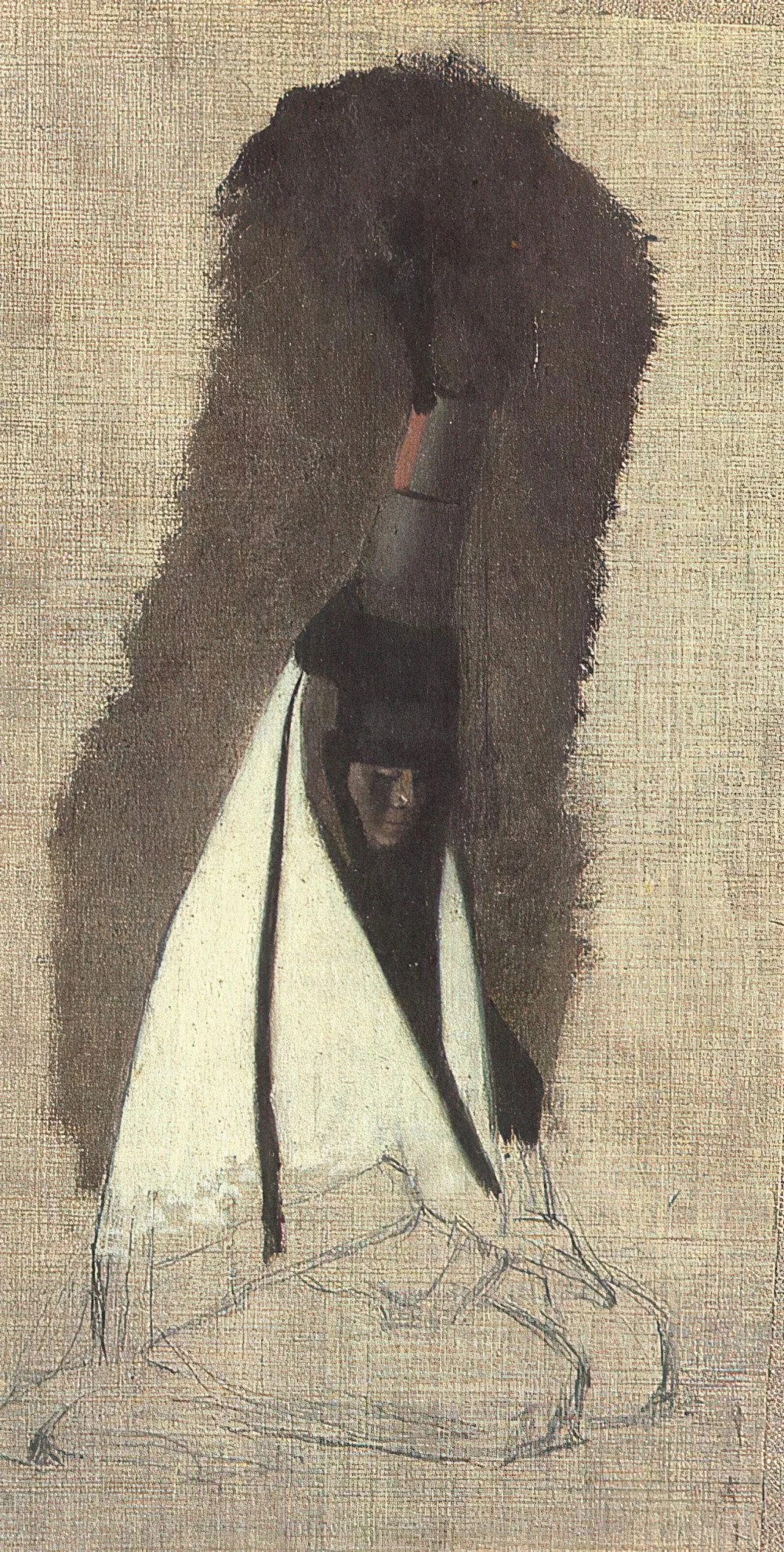

E. M. Sidorkin. Lullaby. 1966/RIA

Were the Raids of the Steppe Dwellers So Destructive?

Perhaps the restraint toward captured women in a military campaign was the result of treating a woman as a valuable trophy, as property. Perhaps it was a manifestation of the military discipline characteristic of the steppe, especially given the time constraints of a raid, which is not aimed at conquering enemy territory.

In the episode ‘Reconstruction of the Mongol Attack on the Old Russian Settlement’ of the podcast The Past: Historical Journal, Dr Konstantin Mikhailov, senior researcher in the Department of Slavic and Finnish Archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, talks about the results of excavations of the Great Shepetivka settlement in the Khmelnitsky region of Ukraine where expensive weapons and jewelry of the inhabitants that were killed in the town were discovered untouched. The participants of the podcast discussed the possible reasons for this phenomenon without any sympathy for the invaders, simply as a fact discovered by archeologists. Dr Mikhailov also cites information from Eastern European chroniclers that states that during the invasion, Mongol warriors did not start looting and sharing the booty after victory or capture of a city unless ordered to. This came as a great surprise to their contemporaries, as the behavior of European warriors in similar situations was quite different.

If steppe dwellers could be indifferent to the valuables in the captured city after the battle, they could probably control their urge to violence as well. In any case, this discovery strongly undermines the idea of savage hordes plundering everything in sight and murdering and raping the defeated in the captured settlement.

In his work The Logic of the Heavenly Law: Kök Töre, nuclear physicist Dmitry Madigozhin tries to reconstruct the evolution of mankind’s moral laws by considering their formation and development as a natural process determined by the conditions of life. According to him, the people of the steppes, unable to hide behind stone walls, were forced to develop trust among themselves, including between neighboring clans and tribes, and mechanisms to observe moral laws. Therefore, they severely punished those who betrayed trust and violated the unspoken code of conduct.

E. M. Sidorkin. From the series «The Kazakh epic». 1962/RIA

n the epic cycle The Forty Batyrs of Crimea recorded by the Mangystau narrator Muryn-jyrau, the ancestor of the batyr dynasty Anshybai blesses his son Parpariye. Serikbol Qondybai considers this blessing a code of Kazakh warriors. It contains lines such as: ‘When you defeat the enemy and take his land, Do not touch women and children, Do not make the innocent cry, Do not destroy ancient tombstones. Intoxicated by your strength, Do not humiliate the weak …’

War is a cruel thing. There have been many wars in the history of our distant ancestors—they attacked and defended, shed their own blood and that of others, and were captured and imprisoned. But they had their own unwritten code, their own rules of honor, and they feared losing that honor more than death.