In 1689, centuries before the idea of Shangri-La or Shambhala ever graced the pages of pulp fiction, a mysterious novel introduced European readers to a Greek utopia hidden deep in what is now Kazakhstan. This imaginary land, where sun-worshipping Greeks thrived in secrecy, captured the curiosity of a world still unfamiliar with Central Asia. At a time when European maps of the region were still filled with ‘blank spaces’, these unknown territories became fertile ground for a genre of Western fiction that fused myth, politics, and fantasy, ushering in the golden age of the ‘lost race’ novel. Central Asia soon became the setting for exotic stories of forgotten kingdoms and spiritual paradises. But how did it come to embody such mythic visions? To answer that, we must journey to a time when the lines between geography and legend were blurred.

Mapping the Unknown: Central Asia’s Allure in Fiction

In 1689, at a time when the British Isles were in turmoil over the religious differences between Catholics and Protestants, a remarkable novel appeared in London. Published under a pseudonym, A Voyage to Tartary only ever appeared in a single edition, perhaps a result of the unusual plotline involving the discovery by the book’s hero of a lost civilization somewhere in the heart of Central Asia.

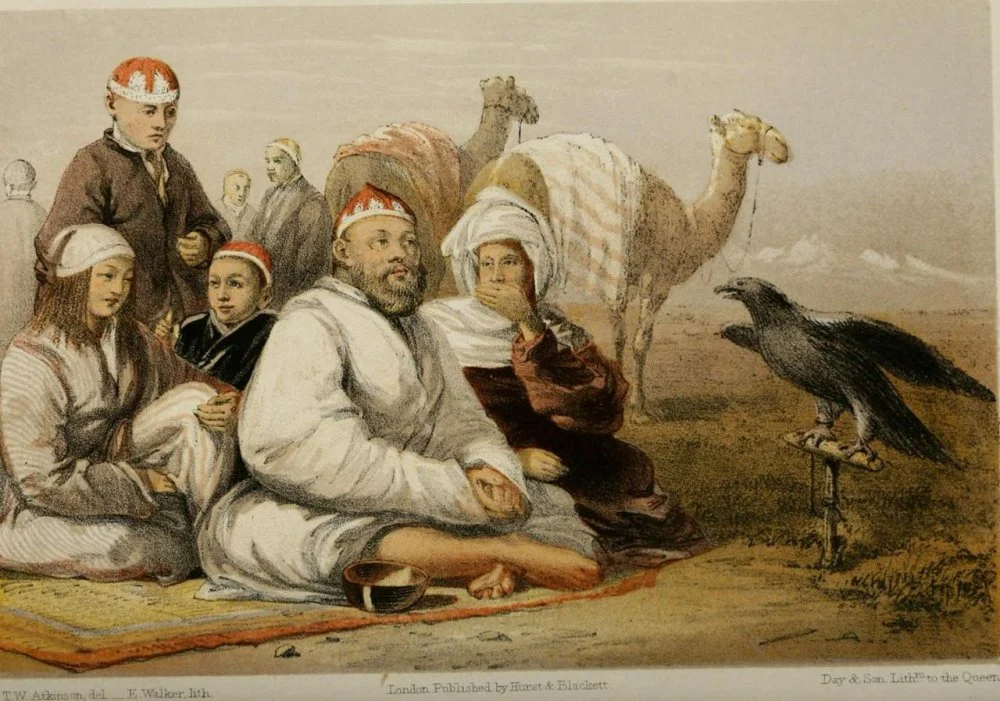

Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen. Oriental meal / Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Indeed, it may even be the earliest example of the ‘lost race’ novel, a genre that during its heyday in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw hundreds of novels appear in bookstores. As the ‘known world’, that is, known to Western geographers and explorers, rapidly expanded and the descriptions of ‘exotic’ peoples, places, and customs became commonplace, novelists took up the challenge to invent more and more improbable civilizations hidden away in remote places.

At first, they wrote about lost peoples in the unwalked forests of South America or jungles of Africa, about remote islands or polar civilizations living underground. But it was not long before the vast territories to the north of India became a subject for fantastic fiction.

The vastness of Central Asia, including the steppes and the gigantic mountain massifs of the Tien Shan, the Pamirs, the Altai, the Karakorams, and the Himalayas, remain to this day some of the least known regions of the world. Russian Imperial troops finally subdued the Turkic Central Asian steppes only in the 1880s and faced resistance and revolt for the next fifty years. Xinjiang, the western-most part of Chinese territory, was not pacified until the communists came to power in China in the late 1940s. British and Indian troops did not subjugate the mountain tribes of northern Kashmir until the turn of the nineteenth century, followed a few years later by Tibet. As we know, Afghanistan was never conquered.

And so, just like the remotest parts of the Amazon in South America or the vast jungles of Central Africa, these regions and their peoples remained little known—except to a handful of ethnographers and explorers—until the mid-twentieth century.

Fashion, clothing in Turkestan, from left, two Tatar women from Turkistan, a pair of Kalmyks from Mongolia, and a Kyrgyz shaman, top right a Kalmykhin's head, next to a Kalmyk hat and a Kyrgyz cap below. 1900 / Bildagentur-online/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Heliopolis and the Greek Utopia in Central Asia

Published almost 200 years before any other novel set in the same region, A Voyage into Tartary is something of an outlier. Indeed, its author is something of a mystery as Heliogenes de L’Epy purports to be a Frenchman, but it is widely believed the book was written by an Englishman under a nom de plume. His book describes a journey made in 1663 through Greece and Turkey, across the Black Sea and the Caucasus to the Caspian Sea and then into Central Asia. From ‘Santa Maria’ on the northern coast of the Caspian Sea, the author takes a boat and after landing on the northeast coast, he makes his way eastwards into the present-day territory of Kazakhstan. However, whether the actual author ever made this or a similar journey or not is not clear; and while some of the details appear to be correct, there are also errors. The entire journey there and back took about nine months according to the text, which would have been incredibly fast for this period in history.

The focus of the book, though, is not so much the journey as the discovery of a lost Greek colony that existed as a city called Heliopolis (Greek for ‘City of the Sun’), located to the east of the Caspian Sea. The Greek-speaking citizens of the city explain that following the death of Alexander the Great, the Athenian philosophers became disillusioned with the city-state and, along with their families, abandoned their homes and set off eastward to found a new state. After two years and two months, they had discovered the present territory, which was flat and without a navigable river—and, most importantly, inhabited by any other people.

Priest beside the boat, looking at a map of "Tartaria, China, India". Engraving. 1653 / Library of Congress

Heliogenes, whose mysterious name means ‘sun-born’ in Greek, gives the diameter of the colony as 95 kilometers and says that it is divided into cantons and country seats. The settlers founded the circular city of Heliopolis at the centre of the territory, where 3,000 men over the age of thirty—about a quarter of the population—formed the initial political assembly. All men (and no women) over the age of thirty had the right to vote. The temple in the centre of the city reflected their belief in the fact that the sun sat at the centre of the solar system, a view they claimed they had come to 1,000 years previously. The government was by an assembly, which appointed one person as the primary lawgiver. There was no private property, and food and clothing were distributed freely from storehouses in the city.

Léon Cogniet. Battle of Heliopolis (Bataille D'Heliopolis), 1837. Perhaps the city of Heliopolis, with its rich history, inspired Eliozhen to create his utopian Heliopolis./ Château de Versailles collections

Heliogenes, whose mysterious name means ‘sun-born’ in Greek, gives the diameter of the colony as 95 kilometers and says that it is divided into cantons and country seats. The settlers founded the circular city of Heliopolis at the centre of the territory, where 3,000 men over the age of thirty—about a quarter of the population—formed the initial political assembly. All men (and no women) over the age of thirty had the right to vote. The temple in the centre of the city reflected their belief in the fact that the sun sat at the centre of the solar system, a view they claimed they had come to 1,000 years previously. The government was by an assembly, which appointed one person as the primary lawgiver. There was no private property, and food and clothing were distributed freely from storehouses in the city.

Illustration from the French edition of Francesco Doni's book The Celestial, Terrestrial and Infernal Worlds (Les Mondes célestes, terrestres et infernaux), 1578. A similar utopian city is the City of the Sun by Campanella, which inspired Eliojen to create Heliopolis / Alamy

In terms of external relations, the inhabitants of Heliopolis reported that they bartered with the Great Cham, sending him 300 young soldiers each year as tribute. The ‘Great Cham’ was originally a corrupted medieval title used to describe Chinggis Khan, and later Timur, but generally here refers to a great khan of Eurasia. So far, it is unlikely that the title referred to any particular ‘Tartar’ ruler.

As for their religion, the sun was regarded as ‘the Soul of the World,’ the most beneficent of all the beings, although the sun itself is not a creator god. Heliogenes writes:

I could not find that they had any notion of god after our manner; in regard that as I have said, their philosophy solely depends upon sense.

He gave them a copy of the New Testament in Greek, but they filed it under ‘mythology’ in their great library. They failed to accept the plausibility of Christianity and teased Heliogenes about it as if he were a madman.

King William III of England in Parliament / Alamy

Thus, the book turns out to be an early utopian novel, possibly inspired by political events taking place in England at the time, particularly with the Glorious Revolution (1688–89), when King James II was replaced by his Protestant daughter Mary II and her husband William III of Orange. This event marked a significant shift in power from the monarchy to Parliament, thereby establishing a constitutional monarchy in England. The author may have written his book as a counterpoint to the idea of monarchy and autocracy.

A month later, Heliogenes returned to Europe, although his invitation to his hosts to accompany him was turned down as they had little confidence his homeland was superior to theirs.

From Lost Greeks to Secret Monks: The Evolution of the Genre

Whilst A Voyage to Tartary remains something of an outlier, by the mid-to-late nineteenth century, more conventional lost race novels were beginning to appear. Central Asia does not immediately come to mind when thinking of classic fiction, but it has inspired more stories than one might expect. I have, so far, been able to identify more than 140 such novels, ranging from late Victorian ‘fiction for boys’ to stories inspired by British experiences in India and later modernist fiction that dominated the 1920s and 30s. There is even one Romanian science fiction novel from the 1930s based on the travels of the explorers Thomas and Lucy Atkinson!

Thomas Atkinson. Illustration from Oriental and Western Siberia: A Narrative of Seven Years Explorations and Adventures in Siberia, Mongolia, the Kirghis Steppes, Chinese Tartary, and Part of Central Asia". 1858 / Wikimedia Commons

That so much of this literature falls into the lost race category is no doubt due to the huge areas that remained unmapped well into the mid-twentieth century. The fact that so many peoples crossed these lands throughout history encouraged the idea that entire civilizations could flourish in such remote places without being known to the wider world.

By the early twentieth century, Aurel Stein and others had already revealed the existence of real buried cities hidden away in the Gobi and Taklamakan deserts. When ethnographers and linguists proved that ancient Greeks, the followers of Alexander the Great, had settled in Bactria more than 2,000 years ago, it only added fuel to the flames. Giant Buddhas, lamaseries that seemed to exist on little but thin air in the remotest places, new minerals and animals—all these excited the minds of fiction writers.

Giant Buddha displayed at “The Great Art of Dunhuang” exhibition, Shanghai, China / VCG via Getty Images

Amongst the best-known of the lost race novels are James Hinton’s Lost Horizon (1933), which tells the story of Shangri-La, a hidden mountain valley in the Himalayas where a sect of monks had discovered the secret to eternal life. Rudyard Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King, first published in 1888, tells the story of two adventurers who set off for Kafiristan in northeast Afghanistan with twenty rifles and a plan to become rulers of this remote region with its vestiges of Greek civilization. Both books later resulted in acclaimed and memorable films.

Lost Horizon movie poster, top center: Ronald Colman, bottom left: Ronald Colman on a window card, 1937 / LMPC via Getty Images

Kipling also wrote Kim, perhaps his greatest and most famous novel, first published in book form in October 1901. The eponymous Kimball O’Hara is a homeless orphan living on the streets of Lahore, who meets an aged Tibetan lama and becomes his disciple. If that was not enough, he also becomes a trained secret agent deeply involved in the Great Game between Russia and Great Britain.

In addition, many well-known fiction writers of the time added a Central Asian drama to their portfolio. H. Ryder Haggard, for example, wrote a follow-up to his famous 1887 novel She called Ayesha, the Return of She (1905), set in Tibet where the hero Holly meets an abbot in a remote lamasery who tells him a tale of a witch-queen from the time of Alexander the Great.

Actress Ursula Andress as Ayesha in She / Alamy

World-famous athletics coach and author of more than 100 books Captain Fred Webster’s (1886–1949) Lost City of Light is about the quest by a descendant of the Templars for a forgotten Christian city. He is captured and taken to a dystopian Chinese city that has enslaved the Christians, who are allowed, at night, to live in their own city and govern themselves, and he leads them to freedom.

Boys' Fiction and Imperial Fantasies

Many of these early novels were classic lost race stories, about the Greeks or other lost groups, including the Vikings, Crusaders, ancient Persians, Neanderthals, and so on. But others were simple adventure stories that were mostly aimed at young boys.

Jules Verne, for example, wrote two novels about Central Asia and Siberia. The first, Michael Strogoff (1876), tells the story of a special courier for the tsar, sent to Irkutsk in eastern Siberia to warn the tsar’s brother that a tsarist officer intended to betray the city to the Tartar hordes of Feofar Khan.

Kiralfy Brothers' spectacle poster for Michael Strogoff, circa 1882 / Alamy

The second, published in 1893, is Claudius Bombarnac, known to English readers as The Adventures of a Special Correspondent in Central Asia. It tells the story of a reporter covering the opening of a new (fictitious) railway between the Caspian Sea and Peking in China. Bombarnac hopes that someone on the train will turn out to be a hero and, thus, the focus of the story he is writing for his newspaper.

Le Triomphe de Michel Strogoff movie poster, directed by Viktor Tourjansky, 1961 / Alamy

David Ker, who started out as a journalist but moved to writing novels after he was exposed as a fraud over his coverage of the Russian military campaign in Central Asia in the 1870s, wrote several novels for boys set in that region including: The Boy Slave in Bokhara (1874), The Lost City, or The Boy Explorers in Central Asia (1884), and O’er Tartar Deserts (1898), followed by Ilderim the Afghan (1904).

Illustration from The Lost City, or The Boy Explorers in Central Asia, 1884. Harper & Bros., New York. / Internet Archive

Fred Whishaw (1854–1934), Russian-born British novelist, historian, poet and musician, wrote A Lost Army: A Tale of the Russians in Central Asia (1896), whilst Charles Squire, the famous writer of Arthurian and British legends, wrote The Great Khan’s Treasure: A Story of Adventure in Chinese Tartary (1902).

Other similar boys’ adventures set in or near Central Asia include Condemned as a Nihilist: A Story of Escape from Siberia (1893) by prolific adventure writer George Alfred Henty (1832–1902), whose hero goes south to Central Asia, and his later work Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashantee (1904).

Illustration from the Fred Wishow’s The Great Khan's Treasure: A Story of Adventure in Chinese Tartary / From open sources

The region also features in Talbot Mundy’s King of the Khyber Rifles (1924), L.P. Lyman’s The Hunniwell Boys in the Gobi Desert (1930), Biggles in the Gobi (1953) by Captain W.E. Johns, Hergé’s Tintin in Tibet (1958), and Messer Marco Polo (1921) by Brian Oswald Donn-Byrne.

Along similar lines, Anna Bowman’s Among the Tartar Tents, or Lost Fathers (1861), is set in the thirteenth century and concerns two boys who are separated from their fathers during the Crusades and taken captive by Tartar tribes. As one reviewer wrote:

Boys' novel of adventure in India and Tibet. Many exciting and suspenseful encounters while trekking and encamping in the mountains, glaciers, and steppes, replete with treachery, captives, spies, wild beasts, mysterious caves, robbers, massacres, storms, an earthquake, hunting, Buddhist hermits, Chinese commissioners, convicts, Sikh soldiers, etc.

From Shambhala to Science Fiction

Perhaps the most prolific author of lost race stories set in Central Asia was Martin Louis Alan Gompertz (1886–1951), who wrote under the name Ganpat, the name his Indian troops called him when he served as a British army officer in that country. Having retired as a brigadier in 1939, he moved to Dartmoor to concentrate on writing and fishing. He produced at least eight lost race novels, the best known of which is Harilek: A Tale of Modern Central Asia (1923) and its sequel, Wrexham’s Romance: Being a Continuation of Harilek (1935). Both novels are based on the idea of a classic Greek telepathic culture that survived in the middle of the Gobi Desert, where they struggle to maintain hegemony over a clan of Mongolian shamans.

Ganpat’s other lost race novels include Snow Rubies (1925), The Voice of Dashin: A Romance of Wild Mountains (1926), High Snow (1927), Mirror of Dreams: A Tale of Oriental Mystery (1928), The Speakers in Silence (1929), and Fairy Silver: A Traveller’s Tale (1932).

Another former military man who turned his hand to writing was Mark Channing (1879–1943), a nom de plume for Leopold Jones, a soldier who spent twenty years in India and was mainly active in the 1930s. Four of his books featuring secret agent Colin Gray are science fiction. In King Cobra (1933), the descendants of Prester John—a mythical Christian king who, it was hoped, would save the Christians from the Mongols—are found to be living underground in Tibet.

Illustration from The Book of Wonders (Le Livre des Merveilles), depicting Wang Khan, Khan of the Keraites, as Prester John. 15th century / Bibliothèque nationale de France

King Cobra was followed by White Python: Adventure and Mystery in Tibet (1934). Set in the 1930s, it sees Gray sent on a delicate mission to Tibet. A rebel uprising fronted by political dissident Chorjieff threatens to topple the country into chaos, and Gray must disguise himself as a Tibetan monk and frustrate Chorjieff’s plans. He discovers a subterranean kingdom and a mystical prophecy concerning a white python. In The Poisoned Mountain (1935), Gray must defend India from poisonous gases emanating from a Tibetan volcano, and Nine Lives (1937) features a teleporting lama and an Egyptian cat goddess.

Lamaic dancing at a ceremony in a lamasery in Yerkalo 1905 / Pictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

One of the most interesting novels to appear in this genre was well-known Romanian novelist (and future Romanian head of state) Mihail Sadoveanu’s Cuibul invaziilor (The Nest of Invasions, 1930), inspired by Thomas Witlam Atkinson's Oriental and Western Siberia, which was first published in 1858—even the cover is based on an Atkinson drawing. Sadoveanu’s novel was part of a larger project aimed at reconstructing the life, culture, and customs of various peoples and regions of the world, specifically Scythia, which he linked to the ancient Romanian territory of Dacia, before the development of science and technology transformed them.

He wrote at least two other books on similar themes, Uvar and Noptile de Sanziene. In the 1930s, Sadoveanu believed that science and technology were a powerful menace that condemned everything to uniformity. However, in the 1950s, possibly to conform more closely to Soviet-era politics, Nest of Invasions was republished in a science fiction magazine with a new slant.

The Metal Monster (1920), Abraham Merritt’s fantasy novel, is also set in the Himalayas. In this book, an army of Persians threatens the heroes, who are saved by a godlike woman called Norhala, who controls the lightning and Things, who are living, geometric forms that can combine to form cities armed with death rays and other weapons.

Artist Glen White. Abrahkam Merritt's "The Metal Monster" book cover (1920), published in Argosy All-Story Weekly / Wikimedia Commons

Dozens of similar novels were published in the years leading up to the Second World War. These were the golden years of lost race novels, but by the beginning of the 1950s, a new genre was firmly in control. Science-fiction writers now looked towards lost planets rather than lost continents. Nor was it any longer fashionable to write novels about clever white folk defeating ‘natives’, usually of a different skin colour.

Yellow Men Sleep (1919) by American author Jeremy Lane (1893–1963) concerns the adventures of yet another Secret Service agent, Con Levington, who travels to the Gobi Desert to search for the drug Koresh, and here he discovers an ancient civilization. Gilbert Collins’ (1890-1960) The Valley of Eyes Unseen (1923) is about lost Greeks in Tibet who have evolved into giants with advanced scientific knowledge.

Harold Lamb, who wrote extensively about the history of Central Asia, wrote at least three novels based in the region. The House of the Falcon (1921) is set in Afghanistan, where ancient sun worshippers live in the Forbidden City of the Sayaks; Marching Sands (1920), which is a story about the Wusun, crusaders who live undetected in the Gobi desert in Mongolia; and A Garden to the Eastward (1950) set in a secret valley called Araman ‘somewhere in Kurdistan’.

Harold Lamb’s Little lost lambs book cover / From open sources

Author John Taine—a nom de plume for Eric Temple Bell (1883–1960)—was a Scots-born mathematician and one of the few qualified scientists to write science fiction. While working at the University of Washington, he wrote several sci-fi books, two at least of which are set in Central Asia. The Purple Sapphire (1924) tells the story of a group of adventurers who discover an ancient valley where a special mineral with incredible powers has been mined by an ancient race. That was followed much later by The Forbidden Garden (1947), which is about the search for soil from a remote part of Asia for the cultivation of flowers that can destroy humanity.

John Taine’s (Eric Temple Bell) The Forbidden Garden book cover/ Wikimedia Commons

American script writer and film director Perley Poore Sheehan’s The Abyss of Wonders, first published in Argosy, the well-known American magazine, in January 1915, is set in the Gobi Desert, where a technologically advanced race is discovered. A later novel, The Red Road to Shamballah, was published in serial form in 1932–33 and describes how his hero, Pelham Shattuck, finds his destiny in the Himalayas after an ancient monk bestows upon him the legendary sword of Kublai Khan. Wielding this sacred weapon, Shattuck sets off to reunite an empire and create the fabled Shambhala.

Nicholas Roerich. Command of Rigden Djapo, 1933. The Red Road to Shambhala is connected to the myth of Shambhala, much like many of Nicholas Roerich’s works. / Nicholas Roerich Museum, New York / Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

I have uncovered at least another thirty or so lost race novels set in Central Asia, some of which are worth reading, but most of which sit firmly in the boys’ adventures category. But as the Second World War approached and the world shrank, the genre began to tire. Soon, it began to fade in the public interest and before long, it was only the dramatic cover art and the catchy titles that drew dedicated readers to track down the few remaining copies, many of which today sell for hundreds of dollars. Keep your eyes open—there are still a few out there.

Roy J. Snell’s Panther Eye book cover / From open sources