On the eve of one of Kazakhstan's most ambitious Italian fashion exhibitions, taking place from 26–28 September 2023, we decided to delve into why footwear crafted by Italian masters is regarded as the pinnacle of shoemaking art. This exhibition will feature the most uncompromising facet of the fashion world—Italian footwear. While the significance of a T-shirt may well remain ambiguous, your choice of footwear certainly cannot and goes far beyond the simple matter of prestige. First, shoes are a question of aesthetics, and second, both your comfort and health undoubtedly depend on the quality of your shoes.

The history of Italian footwear often begins with Roman sandals, but this is more a respectful acknowledgment of antiquity than anything else. These sandals, woven from leather or bark, with wooden or metal soles embellished with gold or gemstones, were not necessarily better than the footwear of other regions, such as Egypt, from which many traditions were borrowed. In fact, sandals were specifically adopted from the Ptolemaic kingdom.

Martino Castellani

‘Italy has been at the heart of fashion for millennia,’ explains Martino Castellani, a notable Italian residing in Almaty. He is the director of the Italian Trade Agency in Kazakhstan and the organizer of the Italian shoe exhibition. ‘The Etruscans and later the Romans had a deep appreciation for beautiful fabrics, elegant jewelry, and exquisite fragrances. The Mediterranean Sea played a crucial role in the development of this interest as Rome engaged in trade with the East, including China, through its ports. The first recorded direct Roman contact with China dates back to the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (138–161 AD). Although trade with the east faced interruptions due to barbarian invasions, it experienced a resurgence in the early Middle Ages. Italy was home to multiple maritime republics, such as Amalfi, Pisa, Venice, Genoa, Ancona, and the significant city of Ragusa, now known as Dubrovnik in Croatia. Naturally, fashion became a vital part of this trade. The Venetian merchant Marco Polo was one of the earliest Italians to step onto the land that would become Kazakhstan between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries CE, contributing significantly to the popularization of eastern wonders in Western Europe.’

Historians estimate that modern Italian shoemaking has its origins in the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance, with this art owing much to Italy's exceptional ties with the East.

Canaletto. Bucentaur's return to the pier at the Doge's Palace. 1730 / Google Art Project

Indeed, Italian maritime trading cities, especially Venice and Genoa, acted as gateways for Eastern goods entering Europe. They marked the endpoint of the Silk Road, serving as the primary market for items arriving directly from distant Asia, as well as products from Byzantium and later the Ottoman Empire. Venice, in particular, held exclusive rights for diplomatic and trade activities in the Ottoman Empire. Silk, satin, brocade, and velvet—all these materials passed through the hands of Italian merchants and brokers, with the finest goods remaining in the area to be crafted by local artisans for sale.

An essential factor to the success of the Italians was the intricate system of guild relationships that evolved during the division of this lucrative market. For a long time, this system had no true counterparts in other European countries. By being the first to acquire the finest fabrics and other raw materials at the lowest prices, Italian craftsmen enjoyed a significant advantage over competitors from other regions. However, even within Italy, the division of this industry unfolded dramatically, resulting in strict and comprehensive guild laws. These regulations seemed poised to stifle any activity that was within the purview of their rules and restrictions.

Felix de Vigne. Fair in Ghent in the middle ages. 1862/Alamy

In V.A. Fionova's monograph titled Leather and Fur Crafts in Venice in the 13th-15th Centuries, a list of specific categories within a shoemakers’ guild is provided. Each master was restricted to producing only one chosen type of product from these categories: ‘Aside from the actual shoemakers (calzolai), who crafted leather stockings (calzari), shoes (scarpe), and boots (stivali), the guild also encompassed clog makers (lavoranti di zoccoli), responsible for crafting clogs and sandals with wooden soles (usually made from cork oak), cobblers (diabattini), tasked with repairing old footwear, and finally, the “solarii”, who cut the insoles worn beneath stockings, effectively replacing shoes.’

Further, strict regulations governed various aspects of shoemaking. Venetian shoemakers’ workshops could only be situated in the Rialto district. Only those apprentices who were under fifteen years old were allowed to engage in trade there. Prior to this age, it was forbidden to assign actual work to apprentices undergoing training. If an apprentice was caught participating in the production of footwear or any shoe components intended for sale, working on details even as minor as shoelaces, hefty fines were imposed on the master. In addition, each insole had to bear the stamp of the workshop that produced it. In cases of defective or non-compliant products, workshops faced fines, and the owner could sometimes be imprisoned or even expelled from the guild.

Shoe workshop in the middle ages. Engraving / Getty images

Similarly, numerous rigorous rules applied to leather manufacturers. Everything was meticulously regulated—from the types of leather that various tanneries could produce to the age of animals from which these leathers were sourced, the types of tanning agents used, and the seasons during which the tanning of various raw materials could take place. Even the types of covers used for the containers of fresh water brought into the city for tanneries’ needs were strictly defined. Seawater was prohibited for use in tanning, and during the transport of freshwater by sea, precautions were taken to prevent saltwater from contaminating it.

The complexity and profusion of these regulations, however, ultimately benefited the craft itself. Stringency in form often leads to an enhancement in the quality of content, a principle well-known in both poetry and pedagogy.

While a Berlin, Reval (now Tallinn), or Liverpool shoemaker could casually assign apprentices to create poorly made boots from inferior leather and then sell these products to undiscerning customers (and even though quality control existed in many places, it often functioned inadequately), Italian masters were the sternest critics of one another. Hence, the quality of Italian footwear, primarily Venetian and later Florentine, far exceeded that of all others.

The tanner. Miniature of the 15th century./Alamy

Castellani elaborates further: ‘We are a country of small valleys, and traveling from one to another wasn't always straightforward. Since the Middle Ages, when the country was divided into numerous cities and feudal domains, various microcultures began to develop, each with its own recipes, cuisine, and clothing. This ultimately led to tremendous diversity. All of this contributed to the birth of the “Made in Italy” concept, and the true essence of this centuries-old success became artisanal production. The abundance of local workshops created a highly competitive environment where only the most honest, resilient, and entrepreneurial craftsmen survived. With regard to footwear, it is produced in nearly all the twenty regions of Italy, but the largest clusters of workshops and factories are located in Lombardy, Marche, Tuscany, and Veneto along the Brenta River.’

Let's not forget, of course, that it was Italian craftsmen who were the first to discern and select the finest, most fashionable, and highest-quality export goods. They were pioneers in adopting technologies and styles originating in the East, reinterpreting them in a European context, and thus shaping European fashion. Venice was considered the epicenter of luxury, serving as the primary European workshop for crafting precious household items—furniture, glassware, clothing, and shoes—where only the very best items were produced.

Miniature of the 16th century / Photo by: Photo12 / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

In both Venice and Florence, workers mastered the production of certain types of leather, which would not begin to be produced elsewhere in Europe for a very long time. Primarily, this included shagreen and saffian leather. Shagreen (the name being derived from the Italian word zigrino and from sagrï, a word of Turkic origin meaning ‘horseback’) is a textured leather with granulated bumps. It was crafted from the central part of the horse’s hide, where the leather is exceptionally durable. According to guild canon, shagreen leather was traditionally dyed in greenish tones, although deviations were possible. Shagreen was most often used for upholstering furniture, crafting leather goods, and, most notably, binding for books. In the realm of footwear, small pieces of shagreen leather were typically used as decorative elements and appliqué.

Saffian leather, also known as Moroccan leather, is believed to have been a closely guarded secret of Italian craftsmen. They obtained it from Mauritania, sometimes from immigrant artisans who were warmly welcomed, finding apprenticeships in Italian workshops. The tanning and finishing process for saffian leather was highly complex and remained a mystery to other producers for a long time. As a result, the cost of saffian leather was exorbitant, and it was considered, along with silks and brocades, as the ‘material of kings’. Typically, it was dyed in vibrant colors, especially red and blue, and was used to craft the finest boots for both ladies and discerning gentlemen.

Italian shoemakers, however, didn't limit themselves to using only shagreen and saffian. They worked with dozens of types of leather ranging from the super strong to the incredibly thin. Footwear was also often crafted from fur and various fabrics such as wool, brocade, satin, and tightly woven silk.

Moreover, the Italians can be credited with popularizing high heels in Europe. While elevated footwear had been worn earlier—such as the Roman cothurni, which was a high, thick-soled laced boot—by the Renaissance, even the memory of cothurni had faded. In Europe, people wore pattens, which were wooden-soled overshoes with leather straps to protect against street dirt. However, it was from Italy, specifically Venice, that the trend of chopines spread. This term referred to footwear, the idea of which local shoemakers borrowed from China via the Ottoman Empire. These shoes had exceptionally high soles, often reaching up to 20 or even 30–40 cm and were primarily worn by women. There were a number of reasons for this. First, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries CE, having a tall stature was considered an essential element of beauty for women. Second, and more importantly, the long skirts with trains that had become popular among wealthy and noble ladies needed to be protected from the dirty, rough streets. Without such protection, a simple stroll would result in significant financial damage by way of soiled or ruined silks and brocades.

Chopines. Italy. 1600/Alamy

European travelers began writing enthusiastic notes about the beautiful Venetian women, and they were particularly captivated by the so-called ‘respectable courtesans’ or the cortigiana onesta. It’s worth noting that prostitution in Venice was entirely legal—the main requirement was that these women needed to pay taxes, and just like everywhere else in the trading republic, there were guild rules in place. All ladies were classified into different categories, and the highest of them were those ‘respectable courtesans’ who, under no circumstances, offered themselves to everyone but chose patrons rather selectively. The honor of patronizing such a courtesan was a very costly pleasure. The most famous courtesans were also poets, writers, philosophers, and talented musicians. History has preserved the names and works of some of them, such as the splendid Veronica Franco (1546–91), a poet who was adored by all of Venice and visitors alike.

Tintoretto. Portrait of Veronica Franco / Wikipedia Commons

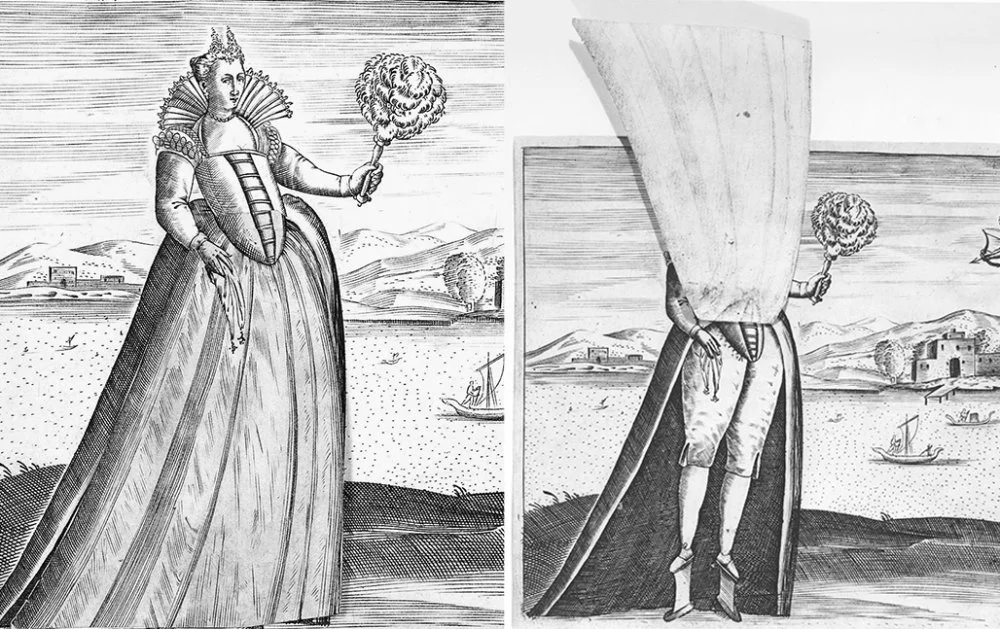

Compared to other noblewomen in Venice, courtesans distinguished themselves primarily by the obligation to wear a yellow ribbon or shawl as a sign of their status. However, in all other aspects, courtesans and aristocrats shared similar characteristics: exquisite perfumes, luxurious dresses in the latest and boldest styles, blonde wigs (or bleached hair) styled into intricate arrangements of braids and loose curls. They also donned chopines, also known as clogs, or pianelle, which were elegant shoes attached to high platforms resembling small shot glasses cinched at the waist. This not only made fashionable women exceptionally tall but also gave them a distinctive gait, a necessity for walking in chopines.

The Courtesan/Elisha Whittlesey's collection, Elisha Whittlesey Foundation, 1955/MET NY

It is worth noting that a young Florentine named Caterina de' Medici shocked Parisians with her chopines. Due to her petite stature of 150 cm, she preferred to elevate herself above her ladies-in-waiting with this unique footwear imported from her homeland. However, these shoes soon lost their uniqueness; fifty years passed, and by the mid-sixteenth century CE, chopines became as popular in France as they were in Italy.

Paris Bordon. Venetian Women at their toilet/Wikimedia Commons

Italy's dominant position as a fashion trendsetter was somewhat shaken after it lost its de facto monopoly on maritime trade in the late fifteenth century CE, continuing into the sixteenth century CE. Spain, France, and later Britain pushed Italian ships out of their familiar routes and established new ones. Meanwhile, manufacturers in Lyon, Berlin, and London gradually learned the secrets of the old masters and began producing fine leathers and precious fabrics themselves. Castellani notes, ‘In Italy, the interest in fashion did not wane, but the trends came from other cities and countries such as high Spanish collars, then Louis XIV and his court in Versailles, and finally Beau Brummell, the founder of British dandyism.’

However, Italian footwear never truly lost its status as the ‘first among the rest’. Some family workshops have existed for centuries, and the principle of quality over quantity has remained unwavering for Tuscan, Milanese, Venetian, and Roman craftsmen. Even with the rise of factories during the era of industrialization, these artisans didn't rush to flood the world with cheap, stamped goods. Instead, they bet on craftsmanship, exclusivity, and tradition, which paid off. While they collaborated less with large trading companies and often sold in small boutique stores rather than large malls, Italian footwear itself was considered a sign of wealth and taste. If we look at famous early twentieth-century footwear designers, Italians steal the spotlight. The house of Gucci was founded in 1921, and Salvatore Ferragamo, the ‘star shoemaker’ enchanted America with his art. The iconic ‘shoe hat’ was designed by Salvador Dali for Elsa Schiaparelli and paid homage to Italian footwear.

A girl in the "shoe-hat" made according to the sketch of Salvador Dali and Elsa Schiaparelli/Getty Images

Of course, the primary consumers of Italian footwear were the Italians themselves. Even modest families typically had ‘their shoemaker’, and Romans, Florentines, and Venetians preferred to have shoes tailored for them, ignoring mass-produced items. The personal shoe lasts of clients occupied half of a workshop's storage space. Thus, Signora Andrina could be certain that the shoes she ordered for her niece's wedding would fit her feet like a glove. This workshop has been outfitting the entire Andrina family for over a century, and that's no accident.

However, everything crumbled after the Second World War. The widespread impoverishment of the Italians dealt a heavy blow to numerous shoemakers. In 1951, for example, the average worker's salary was 23,000 lire, just a mere 10 per cent higher than the minimum living wage for a single person per month. Other segments of the population fared only slightly better, while many, especially pensioners, faced conditions that were considerably worse. Purchasing new shoes had become a luxury for nine out of ten Italians.

The surviving fashion houses swiftly redirected their focus towards the international market. Shoemakers who had fallen into bankruptcy bound their suitcases with ropes and set out in search of opportunities around the world, primarily in the United States. American nationals, initially military personnel and later officials who arrived to help with the post-war reconstruction of Italy, played a crucial role in rescuing the remaining workshops. They bought Italian footwear in large quantities, benefiting from favorable exchange rates and often found ways to bypass customs to send these goods back to their relatives across the ocean.

And like the rejuvenation of nature after a storm, the Italian footwear industry experienced a resurgence, emerging from the ruins. Skilled craftsmen returned from America, where they had gained familiarity with various cutting-edge technologies and were now contemplating how to integrate them into their family businesses.

Castellani notes, ‘After the Second World War, as we embarked on the revival of our country, we swiftly returned to the forefront of the international fashion industry. In 1951, Florence hosted the first Italian haute couture show, and we once again became trendsetters. Today, Milan and Florence stand proudly alongside Paris, New York, and London.’ The ‘Made in Italy’ label became an indisputable symbol of quality in America as Americans discovered the comfort of exceptionally crafted footwear. And as the Italian economy recovered, the newly well-fed population, initially hesitatingly but soon increasingly and enthusiastically, began to make purchases themselves, a reward for years of deprivation and hardship. The 1960s marked a true golden age—many of the renowned companies we know today were established during that era.

However, on this journey, there were temptations that many succumbed to, the most significant of which was to sacrifice quality for quantity, a pitfall often encountered while establishing a strong brand. Italy had indeed become a powerful brand in the post-war years, and Castellani reflects on this, saying, ‘In a competitive world, you need to offer something unique. For instance, a competitive price can easily be found in Latin America, Africa, or Asia, where labor and energy costs are lower. It's a logical choice. Italy, however, is naturally resource-poor. Everything we achieve, we achieve through hard work. Money doesn't grow on trees here. Italians are accustomed to working hard to earn a living, but they also have a penchant for spending their hard-earned money on beautiful things, hence, the demand for quality products and fierce competition. The enduring influence of medieval craftsmanship laws is still felt here. For most, they run a family business passed down through generations and centuries. While not all Italian companies trace their roots back to the sixteenth century, if you wish to enter a market where such companies thrive, you must be prepared to compete with them.’

Today, Italian footwear, produced by all kinds of producers from major fashion houses to smaller private workshops, is considered a vital component of both high fashion and prêt-à-porter collections. Combining ancient traditions of quality with undeniable design leadership, Italian shoemakers continue to stand out in the global arena. While individual designers from England, Japan, America, or France may compete with some of their renowned Italian colleagues as a national industry, Italian footwear manufacturing has no rivals.

From 26–28 September 2023, the La Moda Italiana @ Almaty exhibition will be held in Almaty, organized by the Department for Trade Development of the Italian Embassy (ICE) in collaboration with Assocalzaturifici (the Association of Italian Footwear Manufacturers). This marks the near twentieth year that the finest Italian footwear manufacturers have come to Almaty. According to Castellani, the turnover of fashion goods from Italy accounts for 10–15 per cent of the total trade volume between the two countries. The exhibition will convene at the House of Receptions on 44 Kurmangazy Street from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sixty-five Italian companies will be featured, including leading manufacturers of Italian footwear, clothing, fur, and leather products.

Sophia Loren. A shot from the film "Arabesque"/Legion

Recommended reading

1. Natalia A. Fionova, Leather and Fur Crafts in Venice in the 13th-15th Centuries.

2. Cox, Caroline. Shoe Innovations: A Visual Celebration of 60 Styles. Richmond Hill, Ont.: Firefly Books. 2012.