Two cleaners at work on the timber roof of Westminster Hall, London, UK, 1935/Getty Images

In 1904, while dealing with other important affairs, the British Parliament turned its attention to a most pressing issue: the gothic roof of Westminster Hall. This famous structure, the largest gothic roof in the world, had begun to visibly tremble, signaling a need for restoration.

After all, 600 years is no small span of time. The hall itself was built back in the eleventh century, but the roof—tall, soaring, and creating an unparalleled sense of freedom, light, and air within—was completed in the reign of King Richard II1

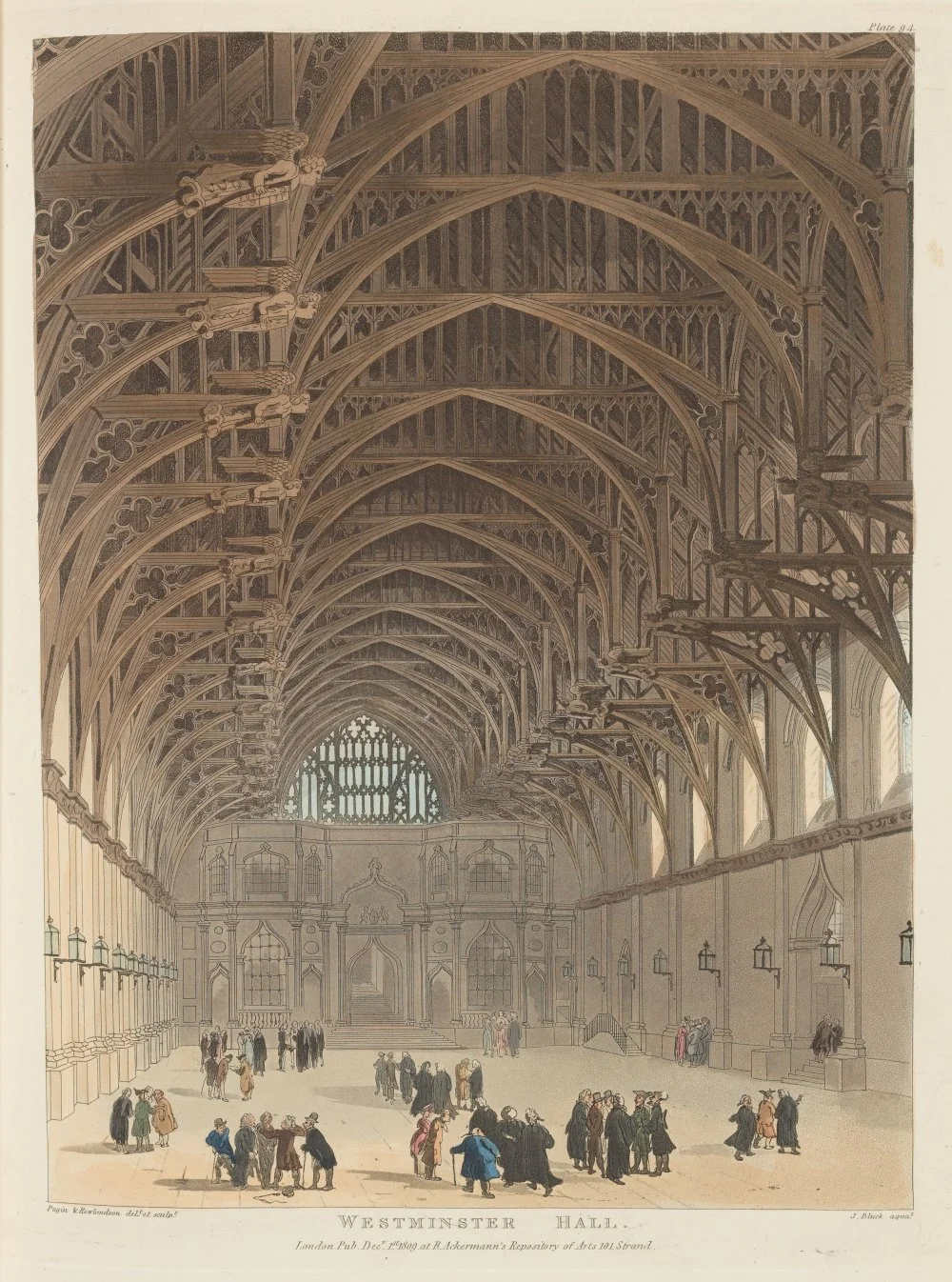

Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827) and Augustus Pugin (1768-1832). Rudolph Ackermann's Microcosm of London . Westminster Hall. November 1808/Wikimedia Commons

The primary challenge was that the hall’s curved ceiling beams were crafted from very old, sturdy oak. For a full restoration, they would need to be replaced, which meant finding robust, healthy, and at least 400-year-old pedunculate oaks to match the size and strength required. This would prove extremely difficult and costly since oak wood was largely imported into England from America, where trees of this age and species were unavailable, as pedunculate oaks were introduced to the continent much later.

However, the famous Limousin oaks of France used to make cognac barrels were of the right age and size, but their wood was too soft, and French winemakers charged such exorbitant prices for them that they may as well have made the roof out of gold.

They were on the verge of sourcing oaks from Ireland, despite a ban on felling such giant trees there, when a message from Sir George Courthope, owner of the Courthope Estate, reached Parliament. He proudly informed the esteemed assembly that a contract had been drawn up in the late fourteenth century requiring the Courthope Estate to plant and maintain a number of oaks sufficient to repair the roof of Westminster Hall. In return, the Crown was obliged to purchase the necessary oaks exclusively from Courthope. The parchment documenting the agreement had been carefully preserved, and the estate’s magnificent 500-year-old oaks were ready and available.

Thus, Westminster’s roof was repaired, the contract with the Courthopes was renewed, and new oaks were planted.