Әлемдегі ең ауыр кітап — Прагадағы Карлов университетінің кітапханасындағы салмағы 75 келі «Гигас кодексі». Ал Шұнақ қорымындағы «Тас кітаптың» салмағы дәл бір тоннадан артық, бірақ ол Гиннестің рекордтар кітабына енбеген. Себебі оның мазмұны әріптермен немесе иероглифтермен емес, суреттермен бейнеленген.

Шұнақтың бірегейлігі оның тастағы суреттеріне де, орналасқан жеріне де байланысты. Ол Бетпақдалада — Аштық жайлаған даланың шетінде орналасқан, бұл аймаққа аяқ басу әлі күнге қиын және өмір сүруге қолайсыз деп саналады. Бірақ ол Киік теміржол станциясынан небәрі 70 шақырым жерде.

Шунақ кластері/Ольга Гумирова

Бұл жерде қыста қатты боран соғып, Ағыбай батыр кесенесінің жанындағы қонақ үйдің шатырын қар басып қалады. Ал жазда мұнда аптап ыстық болады. Заманауи джиппен келген адамға да бұл жерде қолайсыз. Бірақ қола дәуірінде (б.з.д. 2000–800 жж.) адамдар бұл жерге келіп, шағын өзен жағасында көптеген культтық сюжеттері бар үлкен қасиетті орын тұрғызған.

Сол заманда батыл бабамызды жүздеген, тіпті мыңдаған шақырымды еңсеруге не түрткі болды?

Адамдардың бұл жерге алыстан келгенін петроглифтер де растайды. Шұнақтағы петроглифтерді алғаш зерттеген тарих ғылымдарының докторы А.Н. Марьяшев бұл жердегі суреттер Таңбалы тас (Алматы облысы) және Саймалыташ (Қырғызстан, Жалал-Абад облысы) петроглифтеріне ұқсас деп санайды. Кейінірек петроглифтерді зерттеушілер Арқарлы (Жетісу) қорымынан да сюжеті мен ойып салу техникасы бойынша ұқсас суреттер тапқан.

А.Н. Марьяшев жұмыс кезінде/Ольга Гумирова

Бұл аймаққа деген қызығушылықтың бір себебі — алтын кен орындарының болуы деген болжам бар. Қорымға жақын жерде, өткен ғасырларда қымбат металл өндірілген көне шахта орналасқан, ал маңында ежелгі қоныстардың қалдықтары бар.

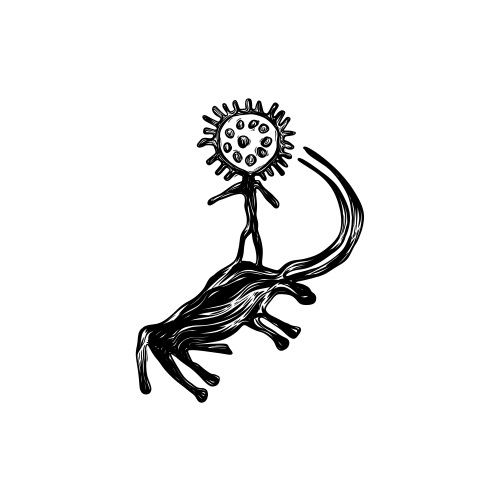

Айрықша петроглифтері бар тас «Тас кітап» деген атау алған. Оған осы атауды берген Ағыбай батыр кесенесінің қараушысы Хамид Мұсабеков. Бұл тас қасиетті орынның ортасында орналасқан. Оны ұзақ уақыт бойы қарап, зерттеуге болады. Суретте 14–15 адамның бейнесі бар, олардың кейбіреуі шайқасып жатыр, кейбіреуі дұға тілеуде, тіпті біреуі қаза тапқан. Бұл — қола дәуірінің өмір мен өлім туралы көп фигуралы комикс-әңгімесі, онда бір немесе бірнеше кейіпкердің, яғни адамның немесе құдайлардың тарихы баяндалады. Нақты не туралы әңгіме екенін ғалымдар әлі анықтай алмай отыр.

Мүмкін, археологтар қола дәуірінен қалған бізге белгісіз осы баянның әрбір жекелеген бөлшегін біріктіргенде, Шұнақтың таңғажайып «Тас кітабын» ақыры оқуға мүмкіндік туатын шығар.

Петроглифтер өзеннің жағасындағы жартастарға қашалған/Ольга Гумирова