With the collapse of the USSR in 1991, artists of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the same as in any other newly formed sovereign republics in the Central Asia, found themselves in a unique situation. Over a brief period, they had to operate beyond habitual ways of cultural production and deal with the absence of institutions that once defined the acceptable manner and meaningful components of the works of art.

These circumstances provided an opportunity for the full-fledged development of the anti-colonial theme—one of the main directions in the contemporary art in Kazakhstan. The first generation of artists to embrace this theme after gaining independence included Säule Süleimenova, Almagül Menlibaeva, the "Qyzyl Traktor" group, Sergey Maslov, Quanyş Bazarğaliev, Erbosyn Meldibekov, Qanat İbragimov, and many others.

Their common goal was to create new artistic practices and forms of identity that went beyond the ideological confines of the Soviet era. Each of them, to varying degrees, grappled with questions of self-understanding and “otherness” in the context of national history and Kazakhstan's position in the globalizing world.

Despite the fact that almost all of those artists were trained in academic painting in the Soviet educational institutions, they held critical views towards the principles of official art. The form it should take and the meanings it needed to convey were determined a long time ago during the reign of Joseph Stalin. Since then, painting and sculpture became the dominant arts, and they were expected to narrate the story of economic modernization, overcoming archaic traditions, and the construction of a new socialist world. Äbılhan Qasteev was one of the main proponents of this new order. The largest art museum at the time in the whole Kazakh SSR, still active in Almaty, bears his name nowadays.

However, as contemporary artists argue, it was the Soviet Union's national policy that set strict boundaries for cultural production in Kazakhstan and other Central Asian countries. The state mandated that artists either adhere to a Euro-modernist style or engage in being ethnonationally oriented craftsmen. In any case, they were required to contribute to the construction of the image of the Soviet person—a common task for the majority of the Soviet artists.

Kazakhstani artists during the Soviet times were required to invent such an image almost from scratch, liberating it from any customs and historical experiences that had developed during the nomadic period. As a result, the "titular nation" of each republic of the Soviet Union was endowed with artificial features that distorted the real past and deprived the peoples of their former complexity, along with the inherent variability.

At the same time, artists were prohibited from discussing pivotal moments in their history. In Kazakhstan, these included aşarşylyq (famine), which claimed the lives of no fewer than two million people; the repression of intellectuals; the concentration of people in correctional and labor camps; the forced relocation of various ethnic groups; the environmental consequences of industrialization; the December uprising of 1986, and many others.

With the independence, many Kazakhstani artists began consistently challenging those limitations. They started seeking new ways of artistic expression and forms of identity for their country, using materials from nomadic, religious, national, regional, and global cultures. Many turned to previously prohibited historical themes while concurrently documenting the changing post-Soviet reality. Their primary mediums became video, performance, photography, and installation.

However, within a few years, the authorities of the independent Kazakhstan decided to resume supporting previous cultural institutions, intending to use them again as a channel for ideological influence. Despite positioning their country as multinational and multicultural, post-Soviet monumental art, mythology, and symbolism revealed an ethnocentric orientation in their policies. This is exemplified, in particular, by the Independence Monument in the Republic Square in Almaty, created by Ädılet Jumabai and Şot-Aman Uälihan.

Independence Monument of Kazakhstan. Republic Square, Almaty/Alamy

The state-sponsored art turned out to be the successor of socialist realism. However, instead of industrialization themes, it presented the audience with depictions of the steppe, the everyday life of nomads, and other objects from their lives. Later, this direction came to be known as "steppe romanticism." Natural landscapes, often accompanied by batyrs (warriors) and wise men, were intended to unite the past and present of national history, presenting it as majestic and continuous, free from the rupture that authorities believed characterized the Soviet era.

Yessengali Sadyrbayev. Morning in the steppe. 2007

Those artists who chose to work with anti-colonial themes perceived that nation-building attempt as a continuation of the Soviet era and criticized it for imposing false and simplified visions about themselves on society. The government's actions were seen as an attempt at internal colonization, which they deemed necessary to halt, initiating the search for alternative identities.

The majority did not set out to propose specific, independently developed identity projects. Instead, they recognized the importance of exploring different identities, focusing on the process itself rather than formulating ready-made solutions. They engaged in observing people, reflecting on their experiences, expressing them in artistic forms, and subsequently supplementing or reexamining those experiences.

However, life in the era of globalization brought new challenges, to which the next generation of Kazakhstani artists, including Gülnur Mukajanova, Bahyt Bubikanova, Säule Düsenbina, the independent art collective MATA, and others, are seeking solutions. These challenges arise both from the strengthening of national states, leading to a global rise in ultra-right and xenophobic political sentiments, and the climate crisis resulting from the intensive exploitation of nature against the backdrop of a still prevalent culture of consumerism in Western countries.

Such circumstances are pushing the world towards significant social upheavals, and the likelihood of such upheavals is fueled by the absence of an alternative scenario for our humanity development. Kazakhstani artists respond to such trends with critiques of contemporary society and the very logic of Western modernity, raising questions about inventing local cosmologies in opposition.

In general, artists working with anti-colonial themes strive to create a critical understanding of the history and ongoing processes of internal and external colonization within Kazakhstani society. In their works, they demonstrate how any form of expansion—be it Soviet, national, or globalist—embedded certain system of beliefs in people. That trapped them in a distorted understanding of themselves, a trap that each artist tries to overcome using their own, sometimes intersecting, means.

Säule Süleimenova

At every stage of her artistic career, Säule Süleimenova delves into the social and political fragments of the lives of Kazakhstanis during the Soviet and post-Soviet periods. Each of them demonstrates three main themes: resistance to authorities, restoration of human dignity, and the awakening of societal self-awareness. In her works, Süleimenova strives to overcome the dominant styles of socialist realism and Western modernism, along with the belief systems of the modern era. She aims to express Kazakhstani identity through free artistic means.

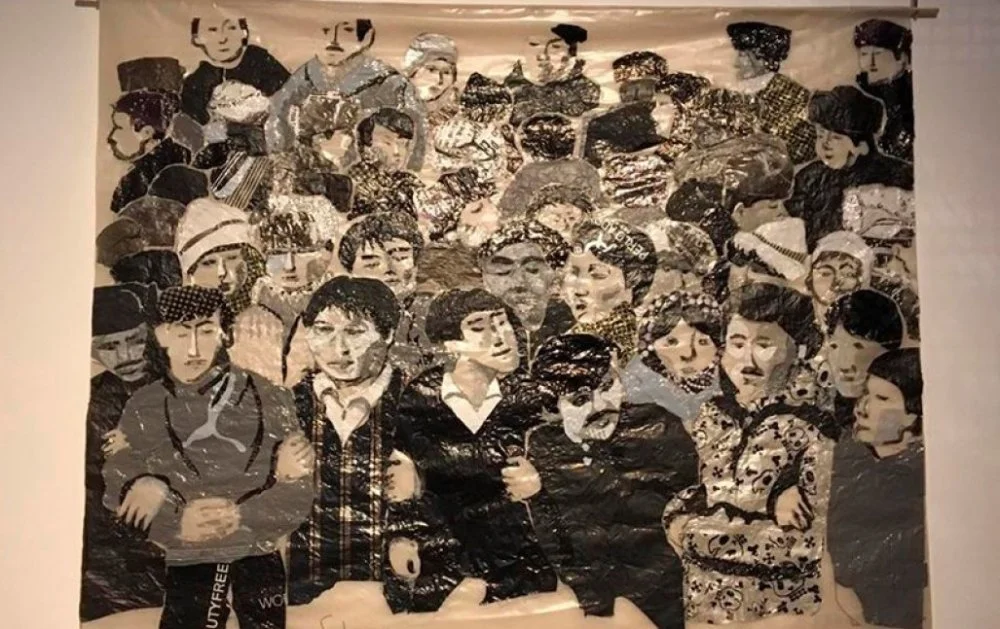

In the later stages of her artistic career, Säule Süleimenova invents a unique collage technique using discarded cellophane bags, which is very far from academic painting. With this, the artist invites us to reflect on the post-Soviet consumerism boom, the flip side of which is an instrumental approach to nature and the people producing consumer goods. By depicting participants in the events of Jeltoqsan in 1986 and Qañtar in 2022, as well as the returning qandastar (ethnic Kazakhs) to their homeland, the artist confronts imperial stereotypes about a politically passive nation, complementing it with a critique of the global consumer society - the main product of the modern era.

Saule Suleimenova. "Zheltoksan. The uprising of the kazakh youth. December 1986"

Almagül Menlibaeva

Almagül Menlibaeva develops a distinctive mode of artistic expression aimed at "Kazakhizing" Euro-modernist languages and forms of art. She focuses on themes of historical heritage and the connection between the present and the past, merging images of traditional culture and modernity in her creative play. The artist draws inspiration from the nomadic manner of celebrating weddings, funerals, and childbirth, as well as the mythology of pre-Islamic Tengriism. In the subsequent stage of her work, Menlibaeva began paying attention to Soviet history, particularly the Gulags, nuclear test sites, and political narratives from Kazakhstan's recent history, such as the ongoing degradation of the Aral Sea.

In her works, Menlibaeva utilizes the steppe landscapes, depleted territories, and abandoned Soviet buildings. However, the central figures are women, dressed either in traditional or modern clothing. Sometimes these women are nude, but whether clothed or not, they are almost always objectified. In doing so, the artist places them in a cocoon of external sexual desire, where they also have a chance to become figures of new power and emerge from their subordinate positions. Menlibaeva blends stereotypes and fiction about the nation with natural disasters and social tragedies. Her openness to the outside world has led to numerous experiments, including some in the fashion market. Some of her works were selected to adorn the Louis Vuitton boutique in Almaty. Currently, Menlibaeva lives and works in Berlin, affirming that local identity can be preserved even at a distance.

Almagul Menlibayeva. Before the solar eclipse. 2009/Aspan Gallery

Qyzyl Traktor

In 1990, shortly before the collapse of the USSR, a group of artists called "Qyzyl Traktor" emerged in Shymkent. The members included Moldaqūl Narymbet, Arystanbek Şalbaev, Said Atabekov, Vitaly Simakov, and Smail Baialiev. The group existed for about 10 years, and then its members decided to pursue their individual careers. Throughout their collaboration, the artists contemplated the theme of cosmopolitanism, intertwining it with the exploration of the outlines of the national "Self." The creative output of "Qyzyl Traktor," predominantly consisted of performances, and was deemed "way too national." As a result, it was regularly criticized for its superficial ethnographism, which found favor in the Western art market.

The artists indeed employed leather, felt, wood, and other traditional materials in the creation of their objects. During performances, they played on handmade national instruments such as dombra, qobyz, drums, and tambourines. They also embraced the aesthetics of "shamanism," making references to archaic Baksy saryny rituals and various Sufi practices. However, the notable thing about them was that beneath all of this, there were practices influenced by classical avant-garde. The primary goal of this artistic group was to achieve harmony in their actions with minimal means of expression, utilizing a scientific artistic toolkit in the process.

"Qyzyl Traktor" emphasized the contradictions between the East and the West. However, the artists considered it important to harmonize the relationship between these poles rather than accentuate their division. They departed from the societal divide inherited by Kazakhstan from the avant-garde political experiments of the 20th century to propose a more refined version of the universe. This intention was reflected in their shamanic performances: through them, the artists sought to heal their land from ailments and establish a new order where tyranny would have no place.

Exhibition of works of the art group "Kyzyl Tractor". 2022

Sergey Maslov

Sergey Maslov extensively worked with Kazakhstani ethnographic materials. In his works, he played with the stability of mythological themes and rituals, creating overtly ironic pieces aiming at national and religious traditions, which consistently provoked strong reactions in local society. For example, in the paintings "Qyz Quu" (literally "girl chasing") and "Dances of Nomadic Peoples," he challenged the staged narratives of "steppe romanticism," restoring ancient erotic meanings to the nomadic rituals.

The painting "Qyz Quu" is enriched with love and passion, resonating with the theme of a restrained flirtation between men and women described in the legend of the equestrian folk game. It conveys the energy of the man's fervent desire to engage in a passionate pursuit of love and the equally passionate desire of the woman to be caught during that racing. This work can also be interpreted as a metaphor for the utopian dream of nomads to conquer European civilization, embodied in the figure of a woman.

Another work by this artist is called "Apotheoses," it is dedicated to George Zubin, who headed the Soros-Kazakhstan Foundation in the late 1990s. This painting alludes to the canvas by Soviet artist Pavel Kuznetsov titled "Mirage in the Steppe." With his painting, Sergei Maslov satirizes the idea that, with good management, Kazakhstan, with its nomadic, imperial, and Soviet past, can apply Karl Popper's conceptual framework of an open society.

Sergey Maslov. Girl chase. 1998 / Aspan Gallery

Erbosyn Meldibekov

Not all artists maintained an optimistic outlook regarding the possibility of halting colonial processes. Erbosyn Meldibekov and Qanat İbragimov, once associated with the independent gallery "Kökserek," conveyed feelings of absurdity and hopelessness through their artistic practices. This was prompted by the fact that, with its independence Kazakhstan failed to overcome the lack of freedom imposed by the Soviet regime, turning people into a powerless mass. On the contrary, conditions in the country gradually paved the way for another wave of authoritarianism, compounded by the challenges of global colonialism.

In his works, Meldibekov deconstructs the theme of identity, collapsing local issues, such as those he associates with Central Asia, with global concerns. His narratives are filled with violence, humiliation, and various forms of dehumanization that initially appear to be inherent features of the region's history. However, the artist encourages viewers to perceive them as negative manifestations of modernity and colonialism, foundational to the projects of the Soviet Union and global capitalism. These sentiments are conveyed by the artist himself, taking a position of the colonized "other."

Wandering between countries and practically lacking rights in any of them, Meldibekov illustrates through his own example how people can be pushed beyond the boundaries of history and the category of humanity itself. In doing so, Meldibekov sees himself as a political artist, whose task is to analyze the political mechanisms of manipulating people to understand why they do what they do: deceive, torture, and kill each other in someone else's interests.

Yerbosyn Meldibekov. My brother, my enemy. 2002/Aspan Gallery

Qanat İbragimov was one of the first Kazakh artists to organize radical performances and happenings. He exploited Orientalist stereotypes about cruel Asians to shock the European-oriented art world. For example, in one of his performances, Ibragimov slaughtered a ram in front of a museum audience and drank its blood from a bowl. Reproducing the rituals of nomads in the style of the Vienna Actionists, he juxtaposed pre-industrial archetypes with the culture of big cities. The artist documented the tension between them, which, in his opinion, excluded the possibility of projecting a new Kazakh identity.

In the later stages of his career, Ibragimov often delved into the theme of economic inequality in Kazakhstan, which seemed unacceptable to him for a country rich in oil. By blending golden and dark tones in his paintings, he pointed out how the ruling class consistently suppresses any form of social struggle to protect the positions of those who profit from the labor of the others.

Kanat Ibragimov. The Koraz bird. Moscow. 1997/ Guelman Gallery

Askhat Akhmediar

Artist Askhat Akhmediar criticizes both the Soviet past with its repressive and instrumental treatment of individuals and the post-Soviet period in the history of Kazakhstan, which continues the previous logic. In his work titled "Brief History of the North," dated 2018, he interprets the image of the capital, Astana, as the quintessence of those two eras. The artist refers to the city as a monument to the Soviet period, as it was closely associated with the virgin lands development project. It also symbolizes globalization, blending attributes of a prosperous Western society with extreme social stratification in developing countries.

He used local reeds to construct an installation resembling a Soviet sickle and hammer. After a brief display at the National Museum in Astana, Askhat Akhmediar transported the installation to the site of the former concentration camp located near the city and dated to the Stalin regime, and he burnt it. It was a simulation of a cleansing ritual from that destructive past, which is the origin of all social upheavals in the present.

In 2021, Askhat Akhmediar conducted a performance continuing this logic. Wearing a shaman's costume, he started obstructing the work of the machinery that was filling a group of small lakes called Maly Taldyköl in the capital for the construction of a residential complex. The artist explained that in Kazakh culture, shamans act as intermediaries between worlds, one of their tasks being to protect nature from the destructive ambitions of modern humans seeking to subjugate it for commercial gain.

Askhat Akhmedyarov. "A brief history of the north." 2018/START Art Fair.

Quanyş Bazarğaliev

The artist Quanyş Bazarğaliev framed his primary works of anti-colonial nature in the series "When All People Were Kazakh," where he attempted to colonize masterpieces of Western art, from Albrecht Dürer to Jackson Pollock, by reimagining their works with the addition of Kazakh ornamental motif "koşkar muiiz" (Kazakh: ram horns) or stylizing the appearance of depicted individuals to resemble Kazakhs.

This series originates from a fictional mythological epic that narrates how Kazakhstan, due to its geographic location at the center of Eurasia, emerged as the only country to survive the comet impact in the North Atlantic, which triggered the melting of glaciers and a global apocalypse. Kazakhstan began accepting survivors from all over the world, and under military rule, built another civilization based on matriarchy, planned economy, and the absolute dominance of Kazakhs, including in the realm of art.

Bazarğaliev chose not to delve into the search for historical truth in the pre-colonial past, opting instead to create his own universe with a unique political system, language, and art history. His goal is to colonize various identities and to comprehensively restructure them the way his vision directs. On one hand, the artist responds to pseudo-historical theories suggesting that Kazakhstan did not exist before its establishment as an autonomous republic within the USSR. On the other hand, he takes the idea of imperialisms and nationalisms to the extreme, criticizing them not only for local but also for any other forms of segregation among people.

Kuanysh Bazargaliev. "When all people were Kazakh". 2013/ Has Sanat Gallery

Gülnur Mukajanova

In the series "Mankurts in the Megalopolis," Gülnur Mukajanova, representing a new generation of artists, explores the transformation of traditional Kazakh values in the era of globalization. She delves into the concept of "mankurtism," contemplating the loss of cultural memory and identity due to significant historical events.

The artist translates these concepts through human bodies devoid of any personal features, and placed in the urban landscapes organized in the spirit of postmodern architecture. In the current context, mankurtism suggests that the cultural suppression of the Soviet era is followed by an equally deindividualizing reality of globalization. The shift in cultural values induced by globalization alters behavior, moral principles, and everyday language. She demonstrates this process, for instance, through the fusion of säukele, which is a traditional Kazakh wedding headgear, with a European wedding dress.

Partly acknowledging the inevitability of cultural fusion, Gülnur Mukajanova nonetheless urges reflection on what Kazakhs should remember in the face of a changing world. This question holds particular significance for her after relocating abroad, where she still doesn't feel completely detached from her national identity. Nevertheless, she sees the real risk of getting lost between traditional and "mankurt" global culture.

Gulnur Mukazhanova. Mankurt #1. 2012/Aspan Gallery

Bahyt Bubicanova

Bahyt Bubicanova explored the cultural changes taking place in Kazakhstan during the era of globalization. Her works capture the tension between the need to adhere to the traditions of the past and the adaptation to the Western model of the present. They focus viewers on the speed of these transformations, often heightened by the use of state violence, as is customary in many other contemporary societies. Bubicanova blends the anxiety arising from this process with sharp irony, using humor to draw attention to the threats that accompany these changes.

Bahyt Bubicanova was interested in the future of nomadic traditions, crafts, and the relationship of the Kazakhs with the nature. On one hand, she developed a cosmology based on the duty of her nation to remember its origins in the face of globalization threats. On the other hand, almost in an avant-garde manner, she desacralized elements of traditional culture. For example, in her work "Womb," she simulated an Eastern carpet, a part of which was cut out and supplemented with a figure resembling the female womb. In doing so, she attempts to break through current boundaries of identity in favor of something fundamentally new, not yet represented in our experience.

Bahyt Bubicanova. Lono. 2016/Aspan Gallery

Säule Düsenbina

Säule Düsenbina dedicated the beginning of her career to traditional painting, using this medium to explore the surrounding world, including its history and memory. Her inquiries led her to question the archetype of the Kazakhs and subsequently attempt to integrate it into the structure of the multicultural contemporary state. In the next stage, Düsenbina created wallpapers, plates, and tablecloths with repeating patterns, concealing surveillance cameras among roses, propaganda symbols, and the exhausted miners of prosperous Kazakhstan.

Her works are a response to topics that are not often discussed in the country's public space. This includes digital authoritarianism imported from China and Western countries, ideological deception stretching from the Soviet Union era, and the exploitation of labor by both local and foreign business elites. Some works describe the unique context of the country, while others, such as ram horns woven into the shape of the Chanel logo, raise questions about the reactionary turn that is taking on increasing global proportions.

Saule Dyusenbina. Bride. 2010

Mata Collective

The independent art collective MATA, consisting of curators and artists such as Aïda Adilbek, Dıldә Ramazan, Janel Shahan, Roman Zakharov, Leonid Han, and other participants, aims to make the liberation from colonial signs a common intellectual task in Kazakhstan. This liberation is intended to address both internal and external political dimensions.

Through their artistic andqyz curatorial practices, they articulate their own decolonial program. The starting point of which is the thought that the universal human values and beauty should be found within the people of Kazakhstan themselves. They do not advocate for distinctions based on ethnicity or culture. Everyone has the right to represent themselves or be represented. Local voices, authors, and practices should take a central place in the public realm. The goal is to make them self-sufficient, eliminating the need for external references.