In this lecture series, medieval historian Irina Varyash discusses how Muslims ruled Spain for approximately 800 years, transforming it into one of medieval Europe's most developed and prosperous regions. The fourth lecture explores how Muslims influenced the habits of Europeans in everyday life, from food to interior design.

The streets of Paris are bustling during lunchtime. A young clerk in a café is looking through the menu du jour, perusing the soup and main course.

– What will you have for dessert? – the waiter asks, and he contemplates whether to choose a fruit salad, a pastry, or a scoop of pistachio sherbet today. Thousands of Parisians are doing the same thing at this very moment, just like hundreds of thousands of other Europeans. Neither the attentive waiters nor their hungry customers pause to consider that they are partaking in, and continuing, an elegant tradition that became popular in the ninth century, thanks to the efforts of a musician from Baghdad.

Household habits

Ibn Ziryab was a singer and musician who delighted the ears of the caliph Harun al-Rashid in his youth. However, at some point, most likely due to court intrigues, he decided to leave Baghdad. In 822, he found refuge in Cordoba at the special invitation of Emir Abd al-Rahman II. Ibn Ziryab intended to establish a school of music and singing in al-Andalus, for which he brought in young male students and women slaves from the East. In addition to composing music and improving musical instruments until his death in 857, this Baghdadi esthete remained a legislator of fashion and refined manners. Among other things, he is credited with creating the sequence of the three-course meal, revolutionizing the way food should be served at a feast. He recommended starting with soup, followed by meat dishes, then poultry, and finishing the meal with sweet pastries and fruits. Naturally, he was also involved in dietetics and culinary arts. Ibn Ziryab believed it was more attractive to set up tables with tablecloths and decorate them with delicate glassware rather than using gold and silver cups.

From al-Andalus, these table manners and etiquette made their way to northern Spain and from there to Europe, along with many other things that we now consider part of our daily standards of living. It is commonly believed that Europeans became acquainted with the high culture of everyday life when they ventured to the East during the Crusades. Having lived amidst luxury in Jerusalem or Antioch, they returned home to France, Germany, or England, wanting to dress in silk, eat from silverware, and enjoy the songs of minstrels. However, Western Europe's acquaintance with the Eastern way of life began before the First Crusade and was facilitated through the experiences of Byzantium, Muslim Sicily, and Spain.

It should be noted that the allure of the Muslim East was so strong that its cultural customs, items, and goods became part of the Europeans’ lives, symbolizing wealth and beauty. For example, if you examine paintings by Italian and Flemish artists from the Renaissance, you will quickly discover that beneath the feet of Christian saints and the Virgin Mary, the brush of the master laid Eastern carpets, ‘Muslim’ in their origin. The garments of Jesus Christ in Giotto's painting The Raising of Lazarus are adorned with intricate ornaments that clearly represent an imitation of Kufic Arabic script.i

Babur's feast scene. A miniature from the Baburnama manuscript. Northern India. 16th century / From the collection of the GMV/ Museum of the East

Agriculture

The Muslims brought to Spain an irrigation system that significantly surpassed the Roman and Visigothic abilities to collect and distribute water. This allowed them to cultivate gardens and engage in agriculture much more effectively than their European neighbors who learned how to implement these systems from them. There are still mills in Spain with water wheels similar in design to those in the Middle East. Thanks to irrigation, the cultivation of crops that required plenty of water—such as sugar cane, rice, oranges, lemons, eggplants, artichokes, and cotton—became possible. The Muslims successfully cultivated many crops, including those known to the Romans, and their Arabic names for many fruits and vegetables entered the vocabularies of European languages and continue to exist in them to this day. For example, the well-known apricot in Roman times was called ‘praecox’ in Latin, which meant ‘early ripening’ and distinguished it from the peach, which ripens later. The Romans adopted this name into Latin from the Greeks, and subsequently, the Muslims acquired it from Greek texts. In their pronunciation, it transformed into the term al-birquk and ‘returned’ to Romance languages, such as Spanish, Italian, and French, in an Arabized form. Several centuries later, the Dutch adopted the name of the apricot in its Spanish variant, and it entered the German, Scandinavian, and Russian languages.

Muslims brought fruits, vegetables, and rice, as well as spices and sugar cane, to Europe, produce that was previously unknown to Europeans. Before this, Europeans used only honey as a sweetener. Until the Age of Discovery, led by the Portuguese and followed by the Spanish, Western Europe obtained spices from the Middle East and India through the intermediation of the Muslims, and the profits from this trade were enormous. Spices allowed food to be preserved for longer without resorting to the long-standing European method of salting meat and fish (corning). They made meat tender and aromatic and possessed disinfecting properties.

The bustling trade between Europe and Muslim countries in the Middle Ages resembles colonial trade: the Muslims sold consumer goods and luxury items like silk and spices in Europe, while the inhabitants of the Roman Latium supplied the East with raw materials like iron, copper, timber, fur, and slaves. It is unsurprising that the term 'slave' in European languages, such as French, English, Spanish, and Arabic, was derived from the ethnonym 'slav', as seen in words like slave and saqaliba. Until the eleventh century, Europeans primarily obtained slaves from pagan peoples, who were mainly Slavic or those ethnically similar to Slavs, accounting for the prevalence of such individuals in the slave trade during that period. They had fair hair, white skin, and blue eyes, which were highly valued in Muslim Spain and the East. With the Slavs’ conversion to Christianity, this source of captives dried up, but the word remained, now applied to dark-eyed Circassians, broad-cheeked Tatars, and swarthy Turks.

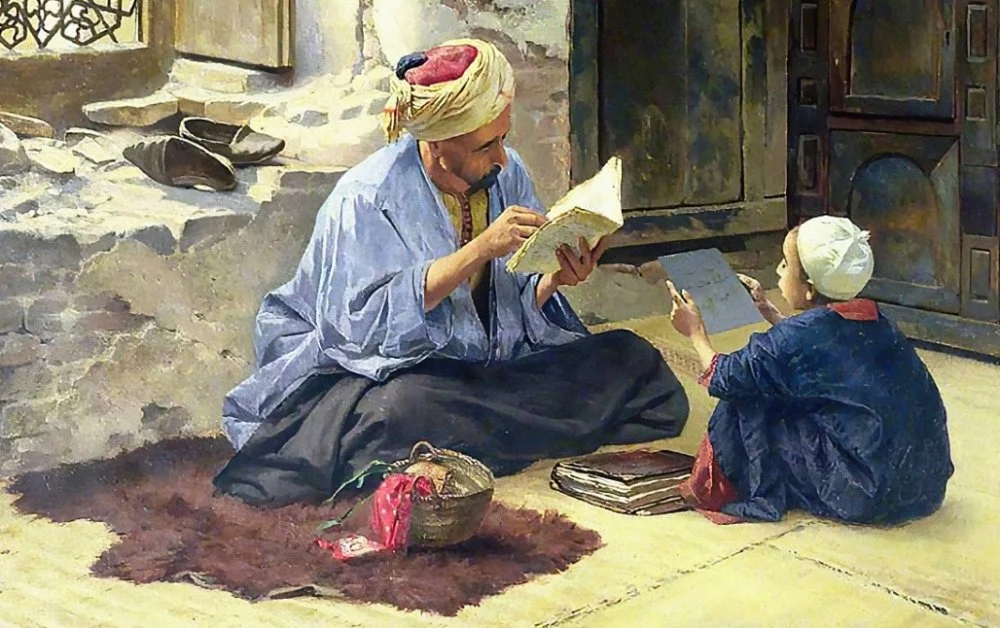

Ludwig Deutsch. An arab schoolmaster. 19th century / Alamy

Language

Muslim standards of living made a strong impression on Europeans, especially challenging the beliefs of those who considered Islam to have originated in the desert among illiterate and savage Bedouins. Contrary to the opinions of the uninformed, Islamic civilization was inherently urban from its inception. It is not surprising that Muslims in Europe developed large and prosperous cities such as Cordoba, Seville, and Granada. These cities were famed for their vast bazaars, palaces adorned with decorative splendor rivaling mosques, gardens, fountains, and waterfront promenades. Additionally, you could also find craftsmen's shops, bathhouses, schools, reading rooms, notary offices, and hospitals in these centers.

Islam set high standards in the field of knowledge, which had a direct impact on the lifestyle of Muslims. There has perhaps never been a society that paid as much attention to literacy as Islam did. Muslim children read and wrote freely, and many of them had the opportunity to pursue further education by leaving elementary schools and studying with private tutors or advancing to the next level of schools, which provided them with accommodation and scholarships. It is also worth mentioning that both boys and girls had the opportunity to pursue education in various fields.

It is not surprising that the prominent Christian figure Paul Alvar, who lived in Cordoba in the ninth century, complained: ‘Many of my fellow believers read the poems and tales of the Arabs, study the works of Muslim philosophers and theologians not to refute them but to learn how to express themselves in Arabic with greater precision and elegance. Where can one find anyone now who can read Latin commentaries about the sacred scripture? Who among them studies the Gospels, prophets, and apostles? Alas! All Christian youths who stand out for their abilities only know the language and literature of the Arabs, they read and zealously study Arabic books ... they have even forgotten their own language, and scarcely one in a thousand can write a coherent Latin letter to a friend. On the contrary, there are countless individuals who can express themselves in Arabic with utmost sophistication and compose poetry in this language with greater beauty and artistry than the Arabs themselves.’

However, the influence of Muslim culture in Europe was not only evident in poetry, literature, or music but also in the more mundane aspects of life. For example, even 200 years after Toledo passed from the hands of Emir Al-Qadir to the Castilian King Alfonso VI, the residents of the capital city drafted sale documents in Arabic. Presumably, the Christians also believed that a document written in Arabic, using their accustomed administrative practices, was more reliable.

Muslim knowledge has always been not only theoretical but also highly practical. As they sought to understand the world created by God, Muslim scholars earnestly studied human beings, delving into the intricacies of their spiritual and physical makeup, striving to alleviate their sufferings and ailments.

A doctor (possibly Al-Razi) examines a patient's urine. Medieval European miniature. 13th century / Wikimedia Commons

Medicine

In the field of medicine, the Muslims initially competed with the Nestorian Christiansi

The Muslims also began to translate medical treatises into Arabic as early as the beginning of the eighth century. They quickly assimilated the legacy of Galen and Hippocrates, supplemented the Greek tradition with Indian achievements, and started opening hospitals, possibly surpassing their Christian teachers. The first reliable information about a hospital in Baghdad dates back to the year 800. In 900, 914, 919, and 925, other medical institutions were established there with the support of wealthy and influential individuals. The revenue from these hospitals was used to pay the staff. Physicians visited prisons to examine inmates, and mobile clinics and pharmacies were established for rural residents.

Similar initiatives were also undertaken in provinces. In Cairo, in 1284, a hospital called Mansuri was opened in a former palace, equipped with the latest medical facilities and able to accommodate 8,000 patients. It contained separate departments for women and men and categorized diseases such as fevers, eye ailments, gastrointestinal conditions, and conditions requiring surgical intervention. Physicians, therapists, and surgeons had already obtained specialization, and they were assisted by pharmacologists, lower-level medical personnel of both genders, and an administrative staff. Muslim hospitals had warehouses, prayer rooms, and libraries where educational textbooks could be found. The level of medical practice was so advanced that among the various practical manuals of that time, one could easily find specialized guides on hospital management, including samples of employment contracts.

The most famous Arab physicians in the Middle Ages were ar-Razi, Ibn Sina and Ali ibn al-Abbas al-Majusi. Over the course of half a century, from 800 to 1300, more than seventy authors gained recognition for their medical works in Arabic. Among them were not only Muslims but also several Christians and Jews, all of whom wrote in the language of the Koran.

Abu Bakr ar-Razi (Rhazes or Abubather in Europe) was an alchemist, a philosopher, and the first head of the Baghdad Hospital. He introduced the practice of recording ‘medical history’, implemented vaccination methods, and used plaster casts to treat fractures. He wrote over fifty medical works, including a treatise on smallpox and measles, which was translated into Latin, Greek, French, and English. He also authored a ten-volume encyclopedia of medical knowledge called The Comprehensive Book. The thoroughness with which scholars of that time approached their material is remarkable, and is clear in this work of ar-Razi’s. For each disease, he presented the views of Greek, Syrian, Indian, Persian, and Arab authors, then added observations and remarks from his own practice, and provided a concluding judgment. Parts of this extensive work were translated into Latin at the end of the thirteenth century in Sicily by a Jewish physician.

Half a century later, Ali ibn al-Abbas al-Majusi (Haly Abbas) created a new encyclopedia, which was equally comprehensive but less weighty. It was the medical work that was one of the first translated into Latin and gained wide recognition in the West. As early as the twelfth century, Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine, considered a masterpiece of Arab taxonomy, was translated into Latin. It became the primary textbook for teaching medicine in Europe until the end of the sixteenth century. Numerous commentaries on the Canon were created in Latin, Hebrew, and other languages. Europeans held these works in such high regard that among the first printed books were commentaries on both ar-Razi’s work and Avicenna's Canon by the Pavia physician Ferrari da Grado. These were printed in 1473 and underwent sixteen more editions over the next twenty-five years. In general, this book is considered the most studied work on medicine in human history, retaining its significance even in the modern era. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, European medicine primarily relied on works translated from the Arabic language.

Alisher Akulov. “The life path and legacy of Imam al-Bukhari”/Open source

Taking all these developments into account, European medieval achievements in the field of medicine and medical services appear rather modest. The oldest institution of higher medical education in Europe is considered to be the School of Salerno, located in southern Italy, which accumulated knowledge of medicine from the ancient, Byzantine, and Arab traditions. By the ninth century, a corporation of physicians already existed there, and in the eleventh century, Constantine the African, who was proficient in several languages, including Arabic, Greek, Syrian, and Persian, translated medical texts for them. He exclusively translated the works of Hippocrates, Galen, ar-Razi, Avicenna, Haly Abbas, al-Hazari, and Isaac Israeli ben Solomon from Arabic.

Interestingly, according to a European legend dating to the seventeenth century, the foundation of the School of Salerno was attributed to a chance encounter between four physicians: a Jew, a Greek, an Arab, and a Roman. At the school, they also studied logic, philosophy, and law in addition to medicine. Anatomy began to be studied in the twelfth century, first using pigs and later the bodies of criminals. Around the same time, the medical school in Montpellier, located in the south of present-day France, became famous. Students from all over Europe came here to study, and it was not by chance. The Montpellier school was influenced by Middle Eastern, Greek, and Italian cultures, as well as Catalan and Muslim-Spanish influences. The city traditionally had a diverse population of Muslims, Jews, and Arab-speaking Christians, who had direct access to the latest advancements in medicine coming from across the Pyrenees. Montpellier’s role as a mediator in transferring medical knowledge and practices from the Islamic world to the Latin world is difficult to overestimate.

In contrast to their Eastern counterparts, Europeans held a long-standing disdain for surgery and surgeons, equating them to barbers and bone-setters. The Church attempted to prohibit the teaching of surgery. It was only with the spread of medical knowledge through translations from Arabic and the acquisition of experience during the Crusades, when Europeans sought treatment from Saracen physicians, that the situation began to change, and the first Western treatise on surgery emerged.

Perhaps the experience of the Crusaders also contributed to Europeans beginning to establish urban hospitals from the twelfth century onwards, specifically intended for the care and accommodation of the sick. However, separate wards for infectious patients were still not being designated, and there were no dedicated physicians. In addition, clinical practice for students only emerged in Europe, drawing again on Muslim experience, in the mid-sixteenth century. Hospitals in Europe initially existed within monasteries and religious institutions, and until the early modern period, they were mostly intended for the care of the poor. Often, they were charitable institutions of mercy and shelter rather than medical establishments as in the East.

Francesco Ballesio. The carpet seller. Second half of the 19th century / Wikimedia Commons

Home Design

Returning to the high standards of living prevalent in Muslim society, which contrasted with Latin customs in many ways, we should also discuss the layout of homes. Muslims paid great attention to hygiene and comfort in their homes. For example, Muslim houses in al-Andalus and Spain were modest on the outside, with whitewashed solid walls and small windows for ventilation at the top. However, on the inside, they were richly decorated and furnished in a thoroughly Mediterranean style, usually incorporating an atriumi

In al-Andalus, the Muslims implemented the ceramic irrigation technique they adopted from the Persians and established the production of polychrome tiles in Cordoba and Seville. The walls of various palace halls (which can still be seen today, for example, in Sintra),i

The levels of literacy and knowledge, and culture of nutrition, hygiene, and health are the markers of development that were well understood by people in the Middle Ages. They are still taken into account in the Human Development Index, an integral indicator adopted by the United Nations Development Program. Just like our distant ancestors, modern economists and policymakers, when assessing the level of development of a country, pay attention to life expectancy, standard of living, and literacy.