Central Asia, the cradle of ancient traditions and a crossroads of diverse ideologies, cultures, and beliefs, has long captivated the imagination of travelers from both near and far. Through their detailed notes and vivid reflections, they have, for centuries, offered a unique, albeit not always impartial, glimpse into the rich mosaic of life in this region: bustling bazaars, nomadic customs, and enduring cultural heritage. In this series of articles, Qalam presents excerpts from their accounts and memories, spanning different eras and revealing the many facets of Central Asia.

Today, we bring you the observations on the Kazakh by the prominent Hungarian explorer and linguist Arminius Vámbéry.

Arminius Vámbéry (1832–1913) was a Hungarian explorer, linguist, and Turkologist recognized for his extensive travels in Central Asia and his contributions to Turkic and Islamic studies. Born Hermann Wamberger into a poor Jewish family in Hungary, he later adopted the name Arminius Vámbéry.

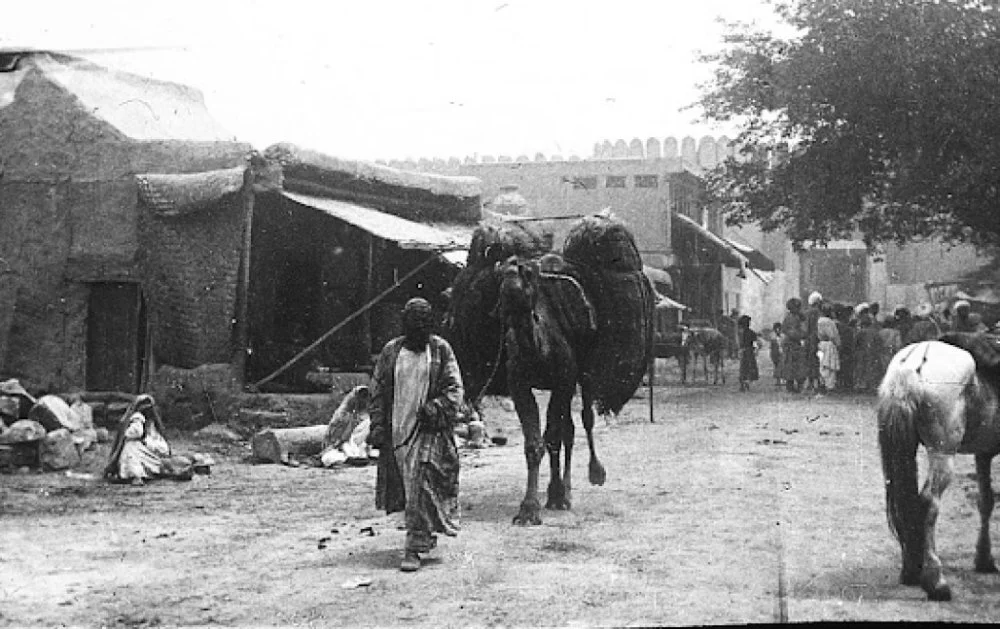

Henri Duval. The Gate of Bukhara / gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Vámbéry gained prominence for his expedition through Central Asia in the 1860s, during which he assumed the identity of a dervish, a Sufi Muslim ascetic, to ensure safe passage. His journey encompassed regions including Persia, Afghanistan, and Turkestan, where he collected significant ethnographic, linguistic, and geopolitical information.

In his book Travels in Central Asia (1864), he provides interesting accounts of the Kazakhs he encountered in the Khanate of Bukharai

Kirghis or Kasaks, as they style themselves, are not numerous in the Khanat of Bokhara, but we will, nevertheless, record here a few notes which we have made respecting this people, numerically the greatest, and by the peculiarity of its nomad life the most original, in Central Asia.

I have often, in my wanderings, fallen upon particular encampments of Kirghis, and whenever I wished to acquire information as to their number, they laughed at me, and said, 'Count first the sand in the desert, and then you may number the Kirghis.' There is the same impossibility in defining their frontiers. We know only that they inhabit the Great Desert that lies between Siberia, China, Turkestan, and the Caspian Sea; and such localities to move in, as well as their social condition, suffice to show how likely we are to err when we at one time ascribe Kirghis to the Russian dominions, and at another transfer them to the Chinese. Russia, China, Khokand, Bokhara, and Khiva, exercise dominion over the Kirghis only so long as the taxing officers, whom they send, sojourn amongst those nomads.

Although their encounter was brief, Vámbéry takes note of the Kazakhs' inclination toward music and poetry, along with their distinct social traditions:

We are surprised to perceive in them so great a disposition to music and poetry; but their aristocratical pride is particularly remarkable. When two Kirghis meet, the first question is, 'Who are thy seven fathers-ancestors?'i

He also contrasts the bravery of the Kazakhs with that of the Uzbeks and Turkmens, whom he was more familiar with, along with their level of religious devotion:

In bravery the Kirghis is inferior to the Özbeg, and still more so to the Turkoman. Islamism, with the former, is on a far weaker footing than with the others I have mentioned. Nor are any of them, except the wealthy Bays, accustomed to search the cities for Mollahs to exercise the functions of teachers, chaplains, and secretaries at a fixed salary, payable in sheep, horses, and camels.