Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908), whose palace name, interestingly, translates to ‘kind and joyful’, ruled China with an iron grip for nearly half a century. Successfully navigating fierce palace intrigues and effectively seizing absolute power, it was clear she had exceptional survival skills and an unbreakable will. Born in 1835, she emerged as the face of China, a country where youth was considered a vice and women were deemed property, at the young age of twenty-five. Cixi's gender, position, and origins can make the notion of her supreme authority seem implausible. However, for resolute individuals, no task is unachievable. Let’s explore the key life principles that shaped Empress Dowager Cixi’s extraordinary rise to power—principles that were evident in her actions and decisions—enabling her to accomplish the seemingly impossible.

Generosity Fosters Alliances

Cixi, born into a high-ranking Manchu official’s family, had been considered attractive ever since childhood and was listed as a potential candidate for the role of a palace concubine. At that time, China was ruled by the Manchu emperors of the Qing dynasty, who rarely chose Han Chinese women as concubines. This was partly due to fears about Han Chinese concubines potentially acquiring influence and conspiring to make attempts on the lives of the ruling elite, as strong anti-Manchu sentiments had persisted since the Manchu conquest of the country in the seventeenth century. Life in the Forbidden City was highly competitive—numerous concubines and servants served the emperor, and many never had the chance to meet him personally.

The future empress, then addressed as Xiǎo Lánhuā (Little Orchid), swiftly grasped the power dynamics of the Forbidden City. She used her resources wisely, selflessly bestowing nearly all the money and valuables she received upon the palace eunuchs, expecting nothing in return. These were acts of generosity and not bribes. Soon, the eunuchs began to empathize with her, keeping her appraised of the emperor's habits, preferences, and actions. They even discreetly orchestrated encounters between the concubine and the emperor, setting the stage for her rise to power.

Never Await a Stroke of Luck—Engineer It

On an exceptionally hot day, the emperor was strolling through the imperial garden when the eunuchs accompanying him directed his attention to a shaded nook. At the far end of this spot stood a pavilion adorned with freshly picked orchids. Suddenly, a soft, enchanting voice filled the air. Seated behind the pavilion was an elegantly attired beauty, her hair bedecked with orchids. She appeared oblivious to the emperor's presence, singing of spring and flowers for her own delight, as if lost in her own world. The emperor was captivated, and soon, Little Orchid was summoned to his chambers. In time, she bore him a son, earned the rank of ‘precious concubine’, and ascended the ranks of the harem, achieving a status akin to that of an empress.

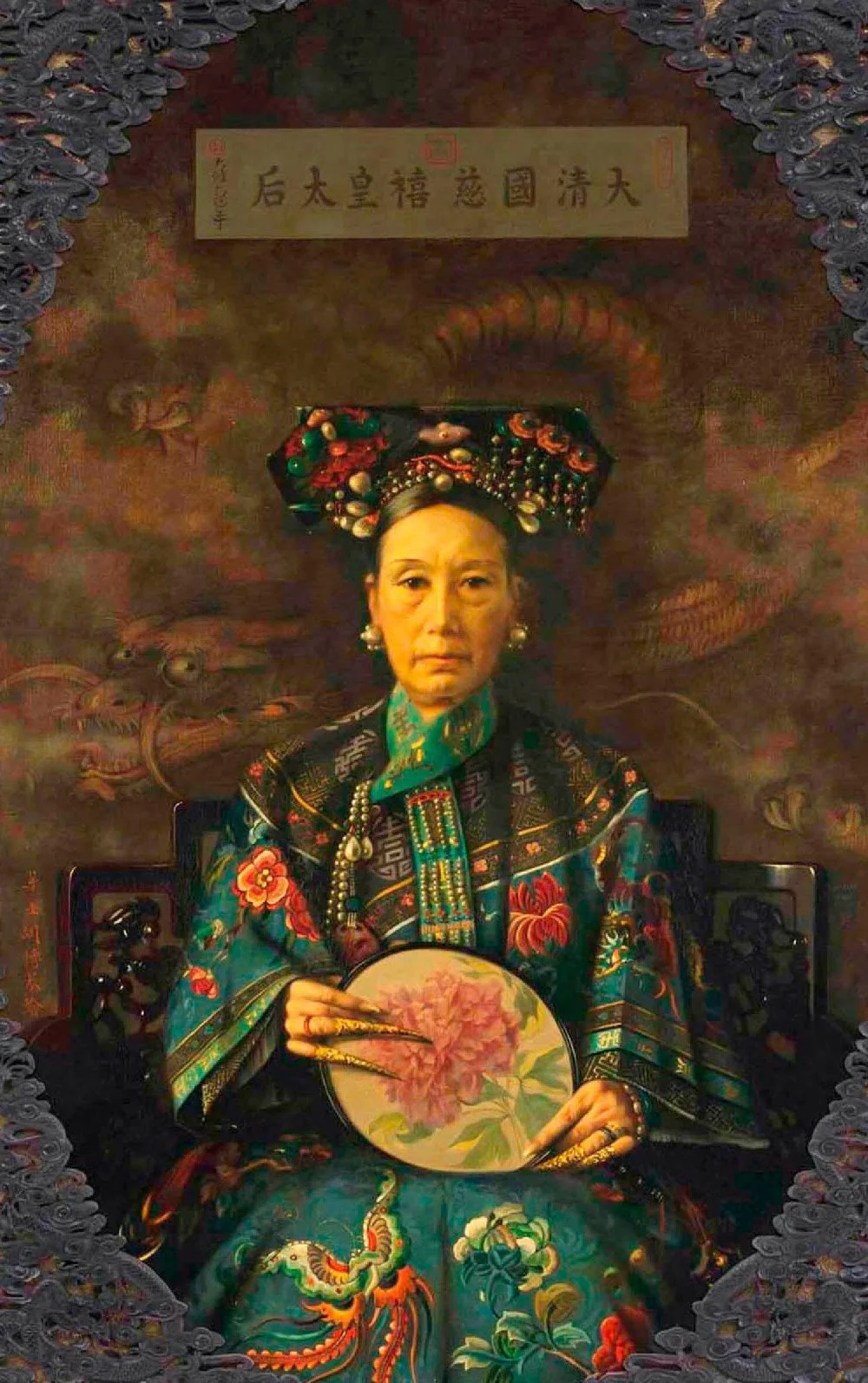

Portrait of Empress Cixi/Alamy

Know the Value of Gratitude

According to most chroniclers, Cixi was known for her vengeful nature, but equally, she was remembered for acts of kindness towards her family. One of the empress dowager’s ladies-in-waiting, Yü Der Ling, who wrote a book about her time in the Forbidden City, recounts: ‘Following her father's demise, Cixi's family fell into poverty. His widow, left with five children, managed to journey to Beijing on a simple boat, aided by friends. When they reached the town of Tunchzhou, a mourning boat docked nearby. An area official dispatched a servant from this vessel with a hundred silver taelsi

‘Regrettably, the servant erred and presented the money to Cixi's mother. Upon discovering the mistake, the official was too embarrassed to reclaim the silver. Not only that, he personally visited to convey his condolences to the widow. This gesture deeply moved Cixi and her mother, prompting them to retain his calling card. Later, when Cixi rose to power, she made sure to trace the whereabouts of the official who had shown her and her family kindness. In a state council meeting, she declared, “This individual possesses great talent and must be promoted.”’

This official's name was Wu Tan, and he grew to be one of the empress's most loyal associates, playing a pivotal role in quelling the Taiping Rebellion, a peasant uprising against Manchu rule.

For a Strong Woman, a Weak Man Is Essential

A formidable leader often needs rivals to sharpen their skills, yet they cannot tolerate competition in their immediate vicinity. This is why some of history's most exceptional rulers have been women. Notably, under female leadership, some of the world's grandest empires (including the British, Spanish, and Russian) have thrived. Figures like Isabella, Elizabeth, Victoria, and Catherine weren't hesitant to surround themselves with exceptional, strong men—commanders, ministers, and politicians. Empress Dowager Cixi, however, operated differently due to her own circumstances—she had limited options. Female rule (or ‘rule behind the bamboo curtain’) was perceived as disruptive to China's societal order. A woman could only wield power as a regent for a young emperor, although this changed during the Manchu era. Cixi's son, Tongzhi, ascended the throne at a young age, and Cixi and Empress Dowager Ci'an were designated as empresses, but real authority rested with a council of regents. Cixi devoted substantial effort and cunning to confronting this council, eventually eliminating or bribing its members to get her way.

Nevertheless, Cixi’s son would eventually take over the reins of power and replace her, a notion she vehemently opposed. In order to delay this transition, she allowed him to indulge in excesses from a young age—opium smoking, concubines, and a life of luxury and idleness. By the age of seventeen, as per biographers, he had become mentally feeble and soon passed away. Following Tongzhi's death, Cixi maneuvered her three-year-old nephew, Guangxu, the son of her sister from another branch of the imperial family, onto the throne. Wielding the real power in court, she intimidated the young Guangxu to the point where he never dared to challenge her. Despite his formal title as emperor, he remained more of a hostage than a ruler. After Guangxu's passing, Cixi succeeded in placing another infant on the throne—her two-year-old grandnephew, Puyi. She herself passed away the next day in 1908, leaving behind a fractured country embroiled in a full-scale civil war.

Never Forget Those Who Harbor Enmity Against You

The ease with which Cixi ordered executions in China left foreigners appalled, and the sheer magnitude of these casualties seemed surreal: 40,000 ‘Yihetuan’ Boxer insurgents executed with up to 100,000 casualties. Even when she officially granted amnesty or reconciliation, those who had previously opposed her often found themselves mysteriously dead within weeks or months. Even the most steadfast of Cixi’s defenders concede that she regarded poison as the preferred remedy for minor domestic issues.

Throughout the nineteenth century, China was in a constant state of turmoil, beset by wars, uprisings, and revolutions. The conflict was pervasive—Han Chinese clashed with the ruling Manchus, citizens revolted against corrupt officials, and foreign powers, including European forces, took advantage of the chaos to pursue their own interests through the Opium Wars and other interventions. Empress Dowager Cixi has long epitomized boundless cruelty in Chinese history, yet modern researchers find her leadership style not significantly distinct from that of her predecessors.

Hubert Vos. Empress Dowager Cixi. 1905/Alamy

People Make Judgments Based on Your Appearance

The empress's wardrobe was a testament to her grandeur and her meticulous attention to her appearance. She had a suite of rooms filled with shelves lined with labeled boxes, each holding shoes, jewelry, and ceremonial robes. Even when she grew old, she never forgot to use powder and blush. She adorned herself lavishly with jewelry, and her most cherished piece was a shoulder cape intricately woven with large pearls. Having a majestic presence in any setting, even the most domestic and informal, was of principal importance to Cixi. Only the wise and the insane do not bow their heads and humble their hearts at the sight of a person dressed in precious attire, and there were few among the courtiers in either category. The rest needed to understand who the empress was—the venerable Buddha and mother of the country, while they were nothing but dust beneath her gilded shoes, elevated high upon platforms.

To Garner Favor, One Must Appear Unpretentious

Katharine Carl, an American artist who painted a portrait of Cixi to be displayed at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, strikingly echoes Yü Roung Ling, a renowned Chinese dancer who enjoyed Cixi's favor. The dancer frequented the palace and left behind her memories of the empress. Both women depict Cixi as delightfully unassuming, given to laughter, somewhat naive, genuinely inquisitive about everything, and warm-hearted. Cixi engaged in conversations with the artist and the dancer as if they were close friends. She playfully poked fun at imperial court formalities, possessed a broad perspective, and exhibited remarkable wisdom. As both Katharine Carl and Yu Zhonglin were invited guests at the court, international stars representing the wider world, we are inclined to believe that the portrait of Cixi they conveyed to the world aligns with reality. The extent of this alignment remains a subject of debate, but thanks to these enthusiastic accounts, we can at least discern the guidelines Cixi adhered to when she aimed to captivate her conversational partners.

What to read

Chang, Jung. 2013. Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China, 1835–1908. Alfred A. Knopf.

Semyonov, V.I. 1979. From the Life of Empress Dowager Cixi. Nauka.

Recommended viewing

The Last Emperor (1987) directed by Bernardo Bertolucci