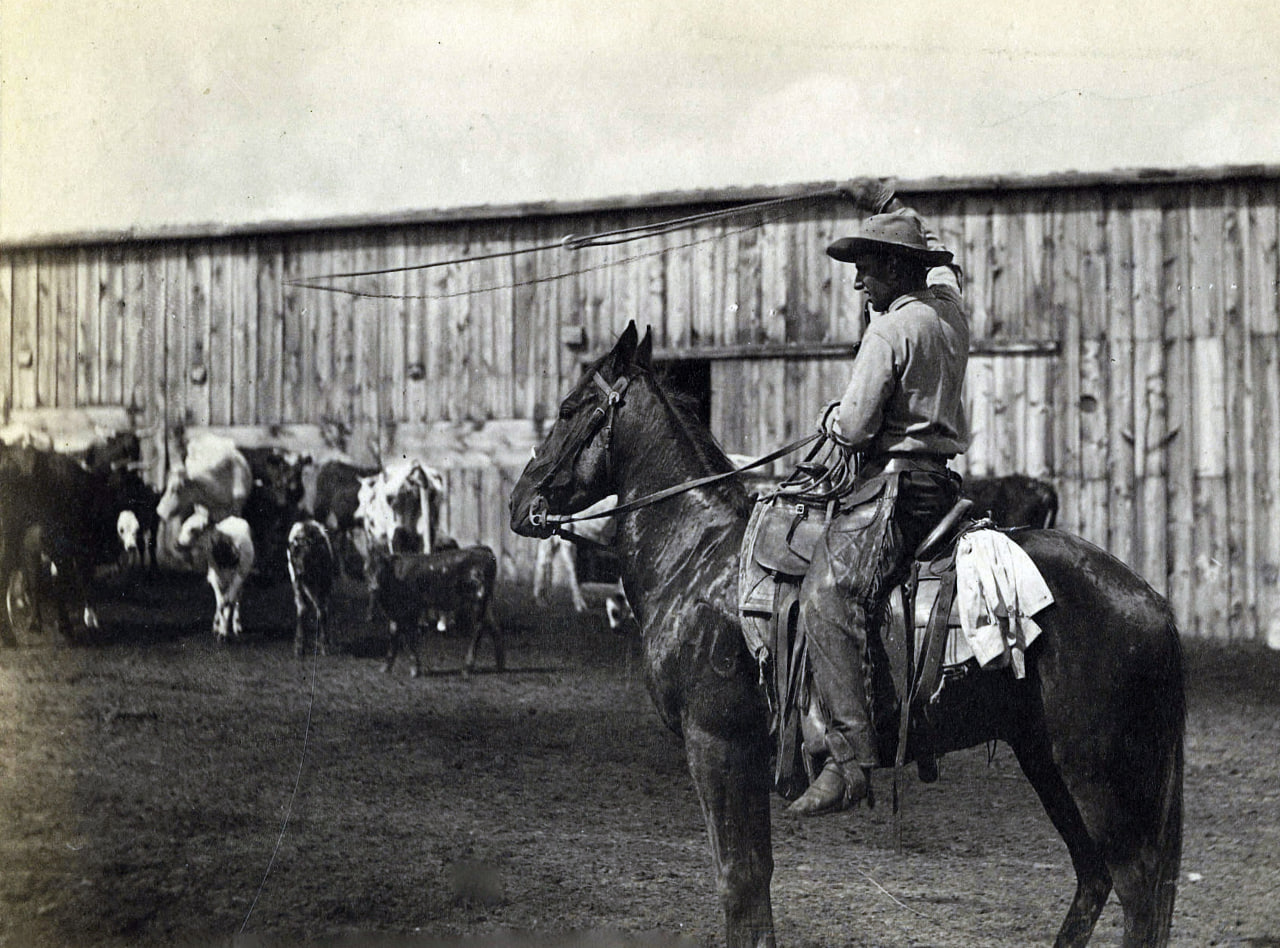

Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville. The Dispatch-Bearer. 1880/Wikimedia Commons

The Ephraimites couldn’t pronounce the ‘sh’ sound, which didn’t exist in their dialect, making ‘shibboleth’ (meaning ‘stream’) impossible for them to say and marking them for death.

Over time, shibboleth came to signify a marker in pronunciation that reveals someone’s social or national origins even if they speak a language well.

This technique for identifying spies, infiltrators, or people from different backgrounds has been used repeatedly throughout history. In 1282, for example, Sicilians, while expelling the French, executed many who failed to pronounce ‘ciciri’, the word for ‘chickpeas’, correctly. During the First and Second World Wars, the Danes used the phrase ‘rødgrød med fløde’ (‘red porridge with cream’) as a shibboleth to catch secret agents. The way a person pronounced the ‘r’ sound often revealed whether they were Danish or a foreign infiltrator. During pogroms on the Jewish community in Tsarist Russia, people were made to pronounce words with the letter ‘r’ because Yiddish, the first language of Russian Jews, had a trilled ‘r’ that Russians perceived as a speech impediment. However, this method was, to put it mildly, unreliable, as it wasn’t only Jews who pronounced ‘r’ in this way. Even members of the upper nobility, whose first language in childhood was often French, which also lacks a clear ‘r’, struggled with it as well.

Vasily Vereshchagin. Interrogation of the Deserter. 1901/Wikimedia Commons

Boris Strugatsky, the famous science fiction writer who had a Jewish father, recalls in his memoirs:

‘Come on, say: “Red grapes grow on Mount Ararat!”’ demanded the relentless crowd surrounding me, pressing in on all sides. ‘Now say “corn [in Russian, the word for corn is kukuruza]!” they shouted, grinning wickedly, elbowing each other, practically bouncing in the anticipation of some fun. I was completely bewildered. Obviously, it was some sort of trap, but I couldn’t figure out what. At the time, I didn’t realize that no Jew could pronounce the letter ‘r’ properly; they would inevitably fumble it and say ‘kukuguza’ for ‘corn.’ I remember thinking that the second I foolishly said ‘corn’, they’d triumphantly yell something like, ‘Gotcha in the gut!’—and then gleefully punch me in the stomach. ‘Come on, say it!’ they urged. ‘Aha, he’s scared! … Go on, say it!’

So, I recited the line about Ararat. A relative silence fell. Confusion was evident on my tormentors' faces. ‘Now say corn …’ I steeled myself and said it. ‘Kukuguza …’ someone muttered, hesitantly tripping over the ‘r,’ but it sounded unconvincing. It was already clear that somehow, I had spoiled their fun.

The most recent cases of using a shibboleth on a mass scale occurred a few years ago in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Ukrainian patrols, while trying to identify and catch suspected Russian saboteurs, would demand that the suspect say ‘palianytsia’ (a type of white bread). This common, familiar word was easy for Russian-speaking Ukrainians to pronounce, but a strong accent would immediately give away Muscovites, Tuvans, or residents of Vologda.