In the lecture series Medieval Art of the West, historian and medievalist Oleg Voskoboynikov presents both significant and lesser-known monuments of artistic culture from the Middle Ages, offering insights through the medieval person’s perspective. In the fourth lecture, the author reflects on authorial anonymity and individuality in the Middle Ages, explaining why demons and pagan gods were depicted in Christian churches.

As is commonly understood, art history considers some of its primary objectives to be the dating, localization, and attribution of specific works. Scientific research encounters specific challenges when dealing with art from the Middle Ages. The majority of the exceptional medieval works of art remain anonymous, which is at odds with modern notions of artist copyright and identity. It is very tempting to view this as another example of the subjugation of the individual by society, of an individual’s creative energy being overtaken by the rules of the guild,i

We can often single out a school, construction guild, or workshop. But prior to the dawn of the modern era,i

Recent discoveries in the study of the icons of the ‘Zvenigorod Tier’i

Here we are faced with one of the most distinctive aspects of the medieval conception of the human personality, which while difficult to comprehend is also evident in other spheres of cultural life. Isn’t it amazing that the identity of the genius behind Corpus Areopagiticum, one of the greatest works of medieval Christian philosophy, was hidden under the name of Dionysius Areopagite,1

This anonymity was never all-consuming, although the practice ceased to be followed only on the eve of modernity. The pioneers it would seem were Italians of the communal age. The following is a typical description of an artist’s virtue in the twelfth century, an inscription to the sculptor Wiligelmo at the cathedral he helped to decorate in Modena:

«You are worthy of honor among sculptors, O Wiligelmo,

The fruits of your labor are now on show to the world.»

What is important is not only the inscription itself, which is probably posthumous, but the fact it is held in the hands of Elijah and Enoch.i

Style and hierarchy

As far back as the sixth century, the Rule of Saint Benedict2

Mosaics of the Palatine Chapel. In the dome, Christ is a Pantocrator in a circle of angels. Italy, Palermo, 12th century / Alamy

As early as the Hellenistic era,4

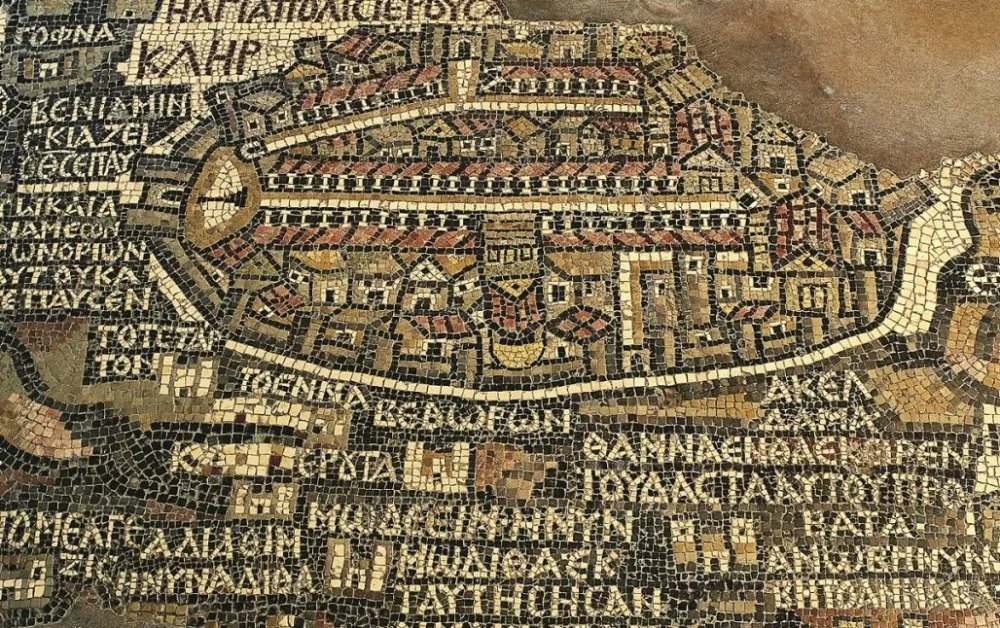

Map from Madaba. A mosaic depicting Jerusalem in the Church of St. George. Jordan, 6th century AD / Getty

The floor mosaic spoke in a “humble style” (stilus humilis), although its contents partially coincided with the “sublime style” (stilus sublimus) of mosaics and frescoes on the walls and vaults. At the same time, floors were sometimes graced with fairly detailed plot compositions. In the basilica in Aquileia (early 4th Century) the floor is decorated as if a sea – an allegory of earthly life. In Ótranto cathedral (12th century) – the floor is decorated with a tree of life, in whose branches we can find “The Fall of Adam and Eve”i

As seemingly simple as this monument is, we must understand that it is a tribute to the hierarchy of styles. No artist would portray a saint or God on the floor, for man to walk over. In iconographic terms this is far from simple, it is on the contrary a bold juxtaposition of a biblical story with a famous pagan narrative perceived as a glorification of earthly power. And as a warning to this very power – whose biggest vice was pride.

This style was not only “an expression of the mood of an era, a people or of personal temperament” (Wölfflin),i

What Capitals Reveal

Let’s try to think about the correlation of style and shape, high and low, permitted and forbidden looking at a specific medieval kind of figurative plastici

“Why are there such ridiculous monsters in the cloister, where the monks devote themselves to their readings? This bizarre ugly beauty and beautiful ugliness? What reason can there be to have in this place dirty monkeys, wild lions, fearsome centaurs, half-man half-beasts, spotted tigers, battling knights and trumpeting hunters? You might see many bodies on one head, or several heads on one body. A four-legged creature with the tail of a snake, a fish painted with the head of a beast. You look and see the front of a horse with the back half of a goat. Or vice versa – a horned head resting on the body of a horse. All around you there is such an unthinkable variety of shapes you would rather read on marble than flip through a book, and stare at these works all day instead of thinking about God’s law. Good Lord! If they are not ashamed of their foolishness, at least let them regret the means they have wasted here!”

We can easily find two-headed and one-headed eagles, centaurs and elephants above the altars and in the cloisters6

However, it was possible in order to achieve a very pronounced rhetoric of the exotic, with richness of forms and styles, since several artists’ guilds worked here at the same time. The kings wanted to demonstrate that anything was possible in their beloved cathedral. The fact that the commissioner of the cathedral King William II the Good appears in mosaics and capitals can leave us in no doubt that the colorful world of his cloister, which surpasses even the best surviving specimens in Provence, Burgundy or Languedoc in sheer scale of design, was the face of authority. As a result, like with other large cloisters, the Monreale complex cannot be deciphered without a degree of ambiguity. However, the hiring of first-class artisans and the significant freedom afforded to them is itself a cultural and political manifesto by the sovereign who built his palace here.

In this sense, in typological terms the joint efforts of the king, archbishop, synodic capituli

Let us not forget that the bestiary of Romanesque capitals, which is connected by direct ties with the earliest handwritten, illustrated bestiaries, is only one such bright and glorious episode in the history of church decoration.

The Ottonian basilica did not feature historicized capitals,9

Abbey of St. Benedict on the Loire / Alamy

This flourished throughout the 12th century, with reference points of Moissac and Toulouse at the beginning, and Monreale at the end. Following Monreale, with the shift from Romanesque style to Gothic,10

Sometimes the diabolical, grimacing world of Romanesque capitals is interpreted as a kind of intermediate space between the floor and vaults, and metaphorically as an intermediate space between the earth and the sky, between carnal man and the spiritual heights. This sea of vices spills not only over the cloister but directly into the church itself (for example, in Vézelay and Autun). The only reason for this is to show the believer the full horror and perversity of sin. Therefore, the more wicked the grin fashioned by the carver, the more convincing the evangelistic proclamation behind it. One can agree in part with this interpretation.

However the overall picture may be even more complex if you try to decipher hundreds upon hundreds of these stone “baskets” as a single phenomenon, ranging from the smallest (for cloister columns) to the largest examples. For example, the choiri

We can also see a whimsical ornamental motif, which was increasingly departing from the “conventionalities” of Romanesque style toward Gothic “naturalism” during the 12th century. Does that mean we’re on track toward a portrait of nature? Although it’s not written anywhere, our instinctive attraction to the system forces us to search for coherence, forethought, completeness of design and wholeness where there is none, since they were not required for the visual and intellectual experience of the commissioner nor the spectators. The historicized capital both constructs the story and at the same time blows away the visual order, because paradoxically its intermediate position is both central within the space of the main nave,11

An Ottonian capital of the year 1000, for example, in Michaeliskirche, Hildesheim erected by Bishop Bernward, consciously rejects the use of imagery, using abstraction harmoniously combined with the wonderfully peaceful space of the basilica, where nothing can disturb the calm of prayer. The historicized capital breaks the silence, requiring an inquisitive glance and is therefore in dialogue rather than monologue with the silent prayer. In Auvergne, for example, unlike neighboring Burgundy, the main doctrinal content of the church was designated to the capitals of the nave and choir, which are statuesque, extremely visible and easy to read.

The central nave of St. Michael's Church in Hildesheim / Alamy

In Western France, at Saint-Pierre d'Aulnay (Charente Maritime), a priest standing next to the altar in the central apse facing the nave could see an elephant on one of the columns of the central cross, whose body is divided in two, encircling the capital basket. Further up but still visible without the need for binoculars, the same priest’s gaze from the same position would fall upon the cautionary tale of Samson.12

Around the year 1200, Bishop Sicard of Cremona wrote a work dedicated to worship which would later inspire the vault of Guillaume Durand. The first book is devoted to the design and symbolism of the church. Sicard “builds” his church based on an idealized image of human society, assigning all the main parts of the building and even materials symbols derived from biblical exegesis. He proposes images of the bishops on the columns, with the suggestion of scaling down their multitude to a symbolic seven because it was said that “Wisdom has built her house, she has carved out her seven pillars” (Proverbs 9:1), and these pillars should be fulfilled seven times by the Holy Spirit, i.e. the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit. The apostles can be found at the foundations of the columns, supporting both the bishops and the building itself.

“The heads of the columns are the souls of the bishops: as our head loves our body as much as our soul loves our words and deeds. The capitals feature the words of the Holy Scriptures that we must consider and live by”.

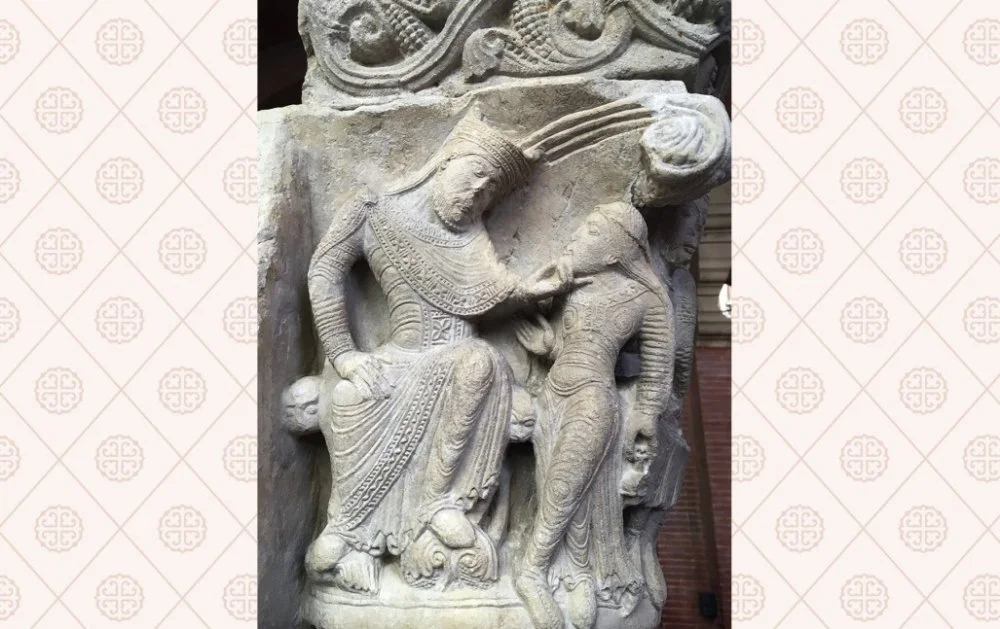

Sicard wrote for the clergy of his diocese, addressing them in his role as primate, as the name of his work “Mitrale” hints, but the influence of his work soon spread far beyond the borders of Cremona and Lombardy. Let’s consider how to interpret his work: if, say, an allegory of vice or a hanged Judas, twisted juggler or centaur are depicted on the capitals, would the column also be a “bishop” or “apostle”? And is Salomé,14

Herod and Salome. A capel from the cloister of Saint-Étienne Cathedral in Toulouse. Toulouse, 12th century. Augustinian Museum / Bridgeman Images

There were in fact enough paradoxes like this in the symbolic language of plastic art. Bernard saw a lack of restraint – even scurrilousness that was unheard of prior to his generation, and unknown to us, as most of it has not survived to this day. Some customers believed that scurrilousness could help to teach monks, but perhaps this was deceptive? Bernard was not alone in his reaction.

Once again: the capital is not a narrow genre designed for a small circle of connoisseurs. If the stained glass window, which had been perfected around the year 1200 when the century of historicized capitals was coming to an end, had been intended as a systematic account of Salvation then the world of capitals would be a polyphonic concert. Perhaps this is why stained glass windows didn’t borrow much from capitals, and this gap in something akin to the transition from early scholastics to classical scholastics – from the school of Chartres to Thomas Aquinas. However, it is in the capital, this “spatial frame” (Fosillon)3, that the medieval artist has achieved such amazing freedom, which neither he nor the connoisseurs of his art have ever forgotten. The physiognomic experiments, naturalism and empiricism of gothic sculptors and artists of the 13th century, their taste in storytelling, detail and amusement are based on a treasure trove of forms accumulated over previous generations. These forms were embodied using not only sublime style, stilus altus and portals, but also in the narrative style of capitals. The Romanesque church learned to speak several languages and passed on its knowledge to the Gothic Cathedral.