A shot from the movie "March of the wooden soldiers". 1934/Gus Meins Charley Rogers/Alamy

Marmite is a cult British product that you either love or hate, but it's hard to remain indifferent. The British consider it one of their national delicacies, whilst those unfamiliar with it have to gather up the courage to taste or even sniff it.

The ‘distinctive taste’ of Marmite (as it is politely referred to in dictionaries and books) is that of very stale and salty beer yeast. The British consider their love for Marmite a national virtue and, in general, it's easy to agree with them. To love this, one needs to have been eating it from childhood or have developed a fair amount of stoicism.

Interestingly, Marmite was not originally a British invention but can be credited to the German chemist Justus von Liebig, who revolutionized science in the first half of the nineteenth century by proving the chemical uniformity between organic and inorganic substances. Having investigated both ‘dead’ and ‘living’ reactions and not finding any fundamental difference in them, Liebig applied his knowledge to the culinary arts and invented several new and truly impressive products. Among them were baking powder, infant formula, and meat broth extract, which later became the basis for bouillon cubes and yeast extract. The latter, in particular, became the main ingredient of Marmite.

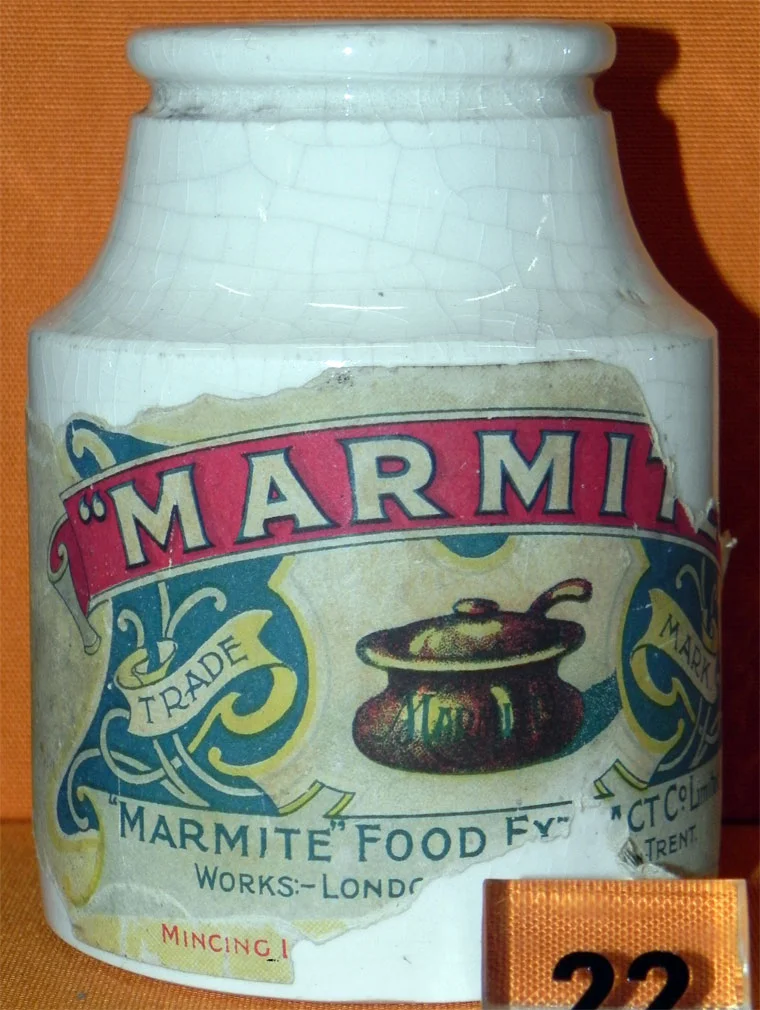

Original faience marmite jar used from 1902 to 1920/marmitemuseum.co.uk

However, Liebig never had the chance to taste real Marmite. The scientist died thirty years before the first factory producing this brown paste opened in 1902 in the United Kingdom. The original recipe included the previously mentioned yeast extract and salt, spices, and celery. The word ‘marmite’ itself is French, meaning a type of pot with a thick bottom, a narrow top, and a lid, in which Marmite was initially sold.

Marmite in the Trenches

It's easy to notice that all the food products in which Liebig had a hand were oriented toward the poor, and this was not a coincidence. During the nineteenth century, urban populations in Europe had grown explosively, and the majority of them were impoverished individuals. People needed cheap and nutritious food. Marmite, produced from the byproducts of beer manufacturing, was actively marketed to the destitute. It was promoted as the cheapest way to eat well and became so popular that by 1907, the company opened a second factory in London. Interestingly, in 1967, the production of Marmite in the British capital had to be closed because residents around the factories complained about the unbearable stench of the production process.

Portraits on toast drawn with marmite. Experimental food society exhibition. London, England. 2013/Getty Images

Marmite did indeed turn out to be a lifesaver for people with meager diets lacking in variety. This paste is rich in all types of vitamin B, which are often deficient in the diets of individuals who can't afford to eat meat, fish, leafy greens, mushrooms, and nuts. During the First World War, Marmite was included in the rations of the British Army. In the 1930s, it was successfully used to treat anemia in pregnant women in India. At the same time, it was used to address the consequences of malnutrition during a malaria epidemic in Sri Lanka.

Through its 120-year production history, Marmite has come to represent something ‘quintessentially English—proper and simple’ for the British. They often spread it on their morning toast, and sometimes they simply eat a small spoonful of Marmite on its own. Moreover, English travelers take it with them around the world because, in most countries, Marmite is simply not available in stores. This British delicacy is perceived by people outside the islands as an exceptional abomination, with virtually no point in trying to sell it. The company Unilever, which owns the brand, even introduced a travel-sized Marmite, a 70-gram bottle, after complaints from British travelers who couldn't take it in their carry-on luggage because the regular packs exceeded the 100-milliliter limit. For several years, Marmite was the most frequently confiscated product in London airports.

Boiling and Evaporating: How Marmite Is Made

The production of Marmite occurs over four primary stages. In the first stage, yeast byproducts from various breweries are mixed, put into a massive vat, and heated. The high temperature breaks down the thick walls of the yeast cells. In the second stage, the ‘soup’ obtained is purified to remove the remnants of the cell walls, making it uniform. In the third stage, the resulting substance is evaporated and filtered again. In the fourth stage, ‘secret ingredients’ are added, which include salt, spices, and vitamins. This mixture is then left to mature for several weeks. Afterward, the prepared Marmite is packaged into jars and sent to stores. Britain has a range of different Marmite-flavored products such as, but not limited to, crisps (potato chips), nuts, peanut butter, and chocolate. Marmite is also added to meat and fish dishes, pizza, soups, and spaghetti sauces, and it is diluted and consumed as a kind of tea. Besides the British, New Zealanders and people from some states in the US also include Marmite in their diet, with various alternatives being stacked on grocery shelves.

Collectible Marmite

The British are collectors, a fact evident to anyone who has visited the homes of locals. The makers of Marmite have capitalized on this national characteristic by regularly releasing limited collections of the product. Fans have already loved Marmite in chili and truffle flavors. They have eaten ‘golden’ Marmite filled with edible glitter as well as a version endorsed by Sir Elton John. On forums dedicated to the product, enthusiasts exchange opinions on taste differences between pastes from different collections and share photos from their home-made Marmite museums.

The marmite collection/marmitemuseum.co.uk

What to read

Hartley, Paul. 2010. The Marmite World Cookbook. New York: Bloomsbury USA.