‘The Fish Market in Antwerp’ by Ignatius Josephus Van Regemorter (1827)

Ever since ancient times, huge schools of Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) have swam in the oceans of the world. This species emerged about 3 to 6 million years ago, long before humans (Homo sapiens) made their appearance. And for millions of years, herring thrived and enjoyed the cold waters they so loved, oblivious to the role they would play in the development of human civilization.

- 1. In the Beginning: Fish and Humans

- 2. The Beginning of Commercial Fishing

- 3. The Problems with Salting

- 4. The Silver of the Sea

- 5. The Main Goods of the Hanseatic Markets

- 6. Gibbing like the Dutch

- 7. An Empire Built on Herring Bones

- 8. Peter the Great and Dutch Herring

- 9. In Memory of William Buckels

- 10. Herring and Early Capitalism

- 11. The Conservation of Resources

In the Beginning: Fish and Humans

Just like its Baltic cousin Clupea harengus membras (Baltic herring), the Atlantic Herring

lives in waters of average temperatures of 6–12°C. The Baltic and North Seas, as well as the polar parts of the Atlantic Ocean, are their preferred habitats.

By the start of the tenth century, the shores of the Baltic Sea, the British Isles and Northern Europe were already quite densely populated. At first, everyone was fishing just for themselves, and herring became a very important part of their diet, giving families an extra chance of survival. Rich in high-quality protein, Omega-3 fatty acids, minerals, vitamin D, and vitamins B12 and B3, herring provided essential nutrition for the northern people.

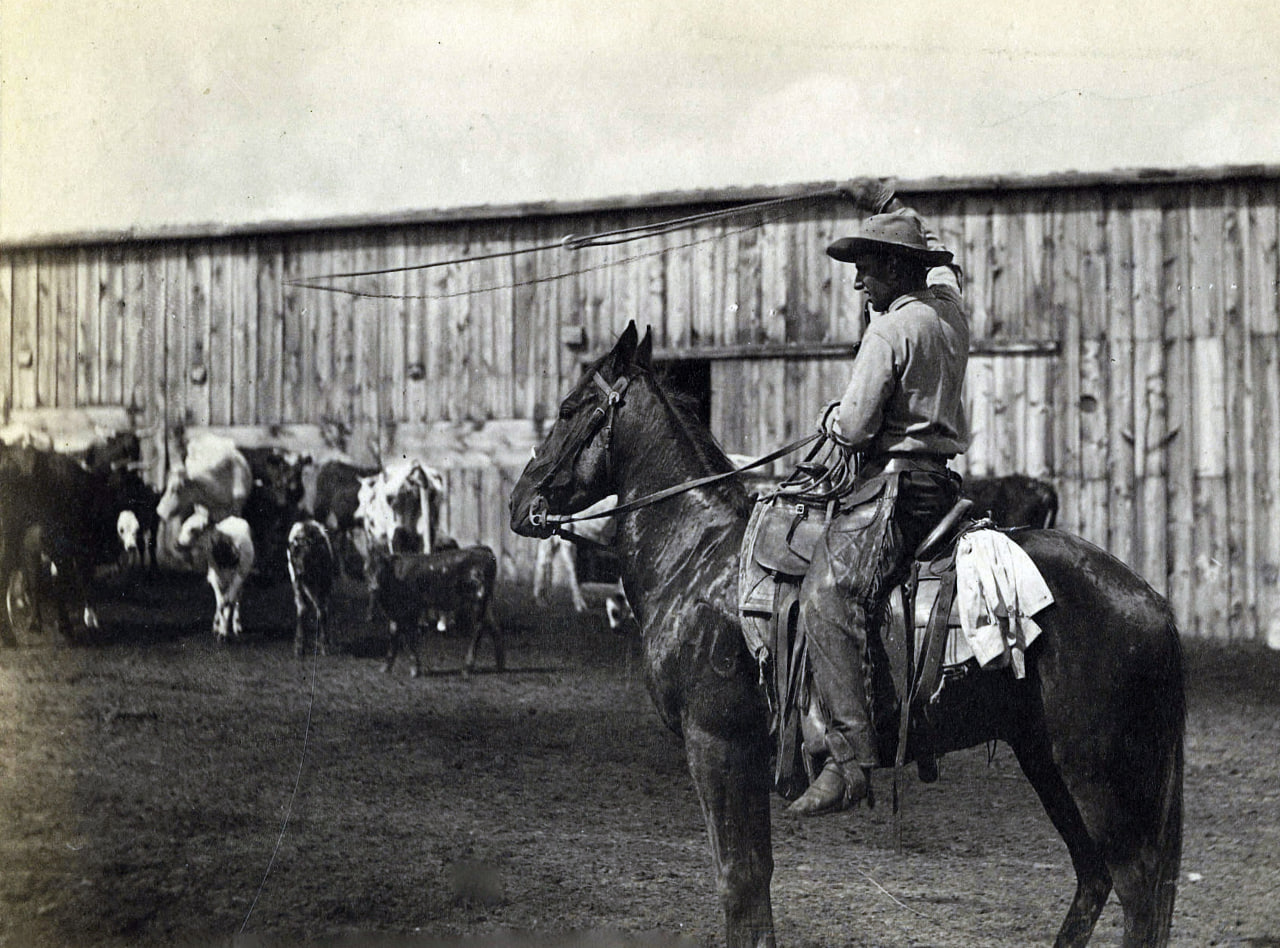

Medieval herring fishing in Scania/Alamy

In those times, many people, or at least those who were not lucky enough to be born into a noble family, spent their lives half-starving or eating a bad diet. Indeed, the greatest deficiency in the poor man's diet was animal protein. Poor people were mostly unable to hunt in Europe’s depleting forests, and keeping their own livestock or even birds was time-consuming and expensive. The fishermen, on the other hand, taking advantage of the limitless resources the sea had to offer, were getting protein in vast amounts.

The Beginning of Commercial Fishing

In the tenth to eleventh centuries, herring fishing was commercialized, and salted herring was being sold and transported across huge distances within Northern Europe. By the twelfth century, the Hanseatic League, a commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe, played the leading role in the herring trade. The league dominated the trade along the coast of Northern Europe, with well-established and properly developed trade routes as well as banks and storage solutions.

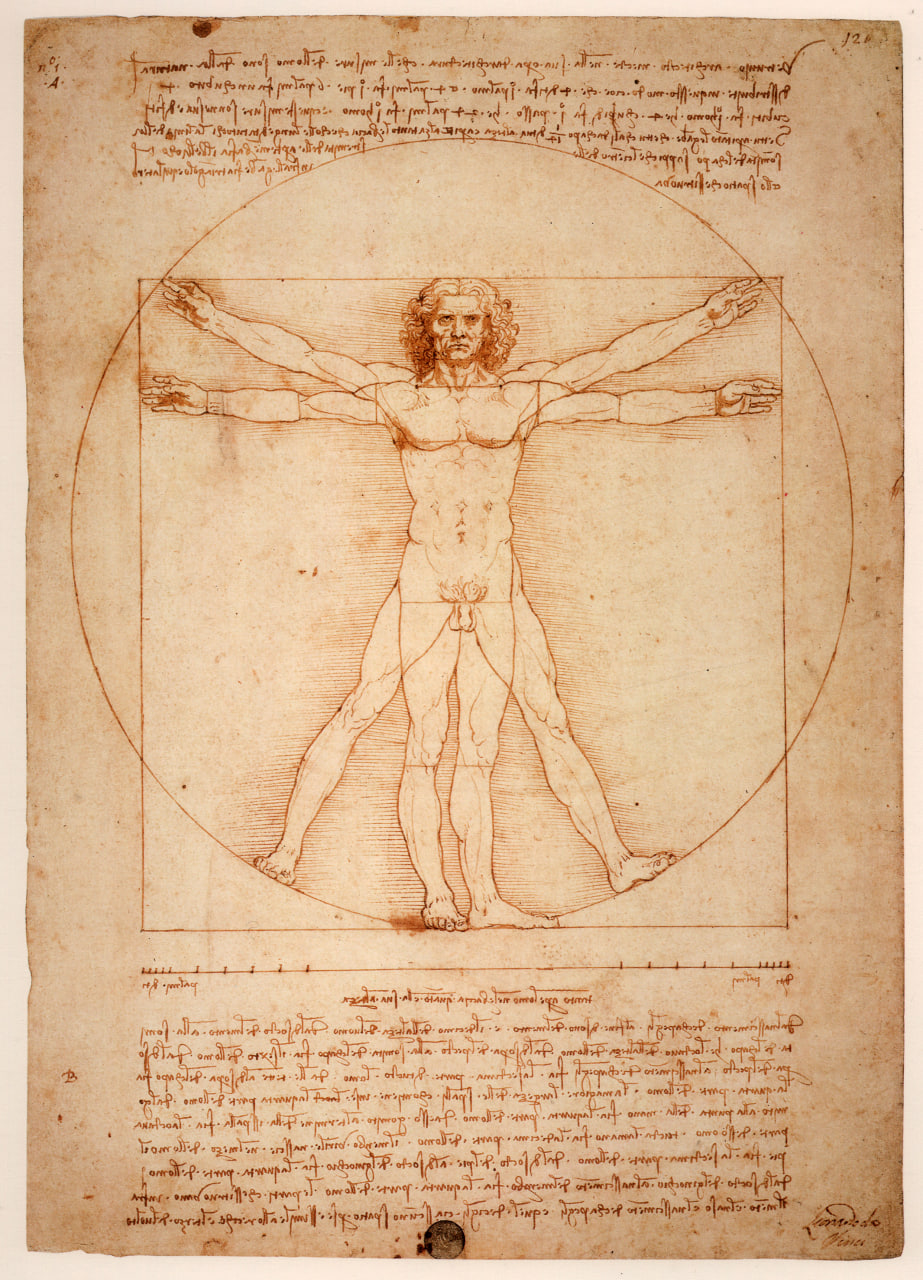

Hamburg Ship Law. Cover picture from the section on sea law 'Van schiprechte' ('Of shipping laws' in Middle Low German) of the Hamburg town law from 1497/Wikimedia Commons

The economies of Europe needed a constant supply of good-quality food to feed their growing populations, but most towns and cities in Western Europe were unable to produce enough food. Fortunately, the herring population was so abundant that according to medieval sources, it could be caught with one’s bare hands.

The Problems with Salting

The biggest challenge for merchants remained the quick delivery to customers’ tables. They had to find a way to process large quantities of fish in a way that ensured it did not go bad for a long period. As the drying process caused the loss of precious fat, the herring would usually be salted, especially given there was no shortage of salt in Northern Europe, thanks to numerous salt mines, techniques for sea salt production, and burning marine clay, which made salt relatively cheap. However, after being salted, the fish would quickly become slightly bitter, and the rich preferred to leave this bony and not-so-tasty fish to the lower classes.

Herring Seller And Boy, 1664, Painting By Gerrit Dou/Alamy

The Silver of the Sea

In the thirteenth century, the Dutch started building larger boats for fishing herring so that they could catch it in much larger volumes, laying the foundations for their future supremacy in the herring industry.

Herring — miniature from folio 112r from Der naturen bloeme (KB KA 16) by Jacob van Maerlant/Wikimedia commons

At the time, the climate was favorable for Northern Europe. The warm period that had lasted from 950 to 1250 was coming to an end, but this was not very obvious. A sudden cold snap and crop failures were coming to Europe, but these would take place only at the beginning of the next century, with the start of the Little Ice Age. For the moment, however, the weather was quite favorable: the winter was mild, the spring and summer sunny, and the towns and cities along the coast of the Baltic and North Seas were growing rapidly. It was during those times that they started calling herring ‘the silver of the sea’.

The Main Goods of the Hanseatic Markets

In the middle of the thirteenth century, the fishing industry in Northern Europe had over 35,000 fishermen and was feeding most of the population in the region. The demand for herring was so great that in the customs registers of Hanseatic towns, such as Lubeck (Germany), where herring fishing took place, herring was marked as the main trade goods in some years. The herring market towed all of the trade, thanks to the abundance and accessibility of this item. Thus, the fish trade turned the Baltic into a very important crossroads between Eastern and Western Europe.

In the middle of the thirteenth century, the fishing industry in Northern Europe had over 35,000 fishermen and was feeding most of the population in the region.

Gibbing like the Dutch

So how did the fishermen solve the problem of salting and transporting herring? How did they rid the fish of the bitterness that salting imparted and make it worthy of the noble table? Legend has it that one William Buckels, also known as William Beuckel or Beuckelsson, a fisherman from the city of Biervliet in the Zeeland province, thought of a way of preserving the fish—having it gibbed before salting it.

Gibbing is a process of preparing fish where the gills and some of the guts are removed, leaving the liver and part of the pancreas, which is responsible for the secretion of digestive ferments. At the same time, the herring is completely drained of blood, so it does not have the bitter taste when salted. Due to the fermentation process that it undergoes, the salted herring becomes tender maatjes (meaning virgin in Dutch) in just one week.

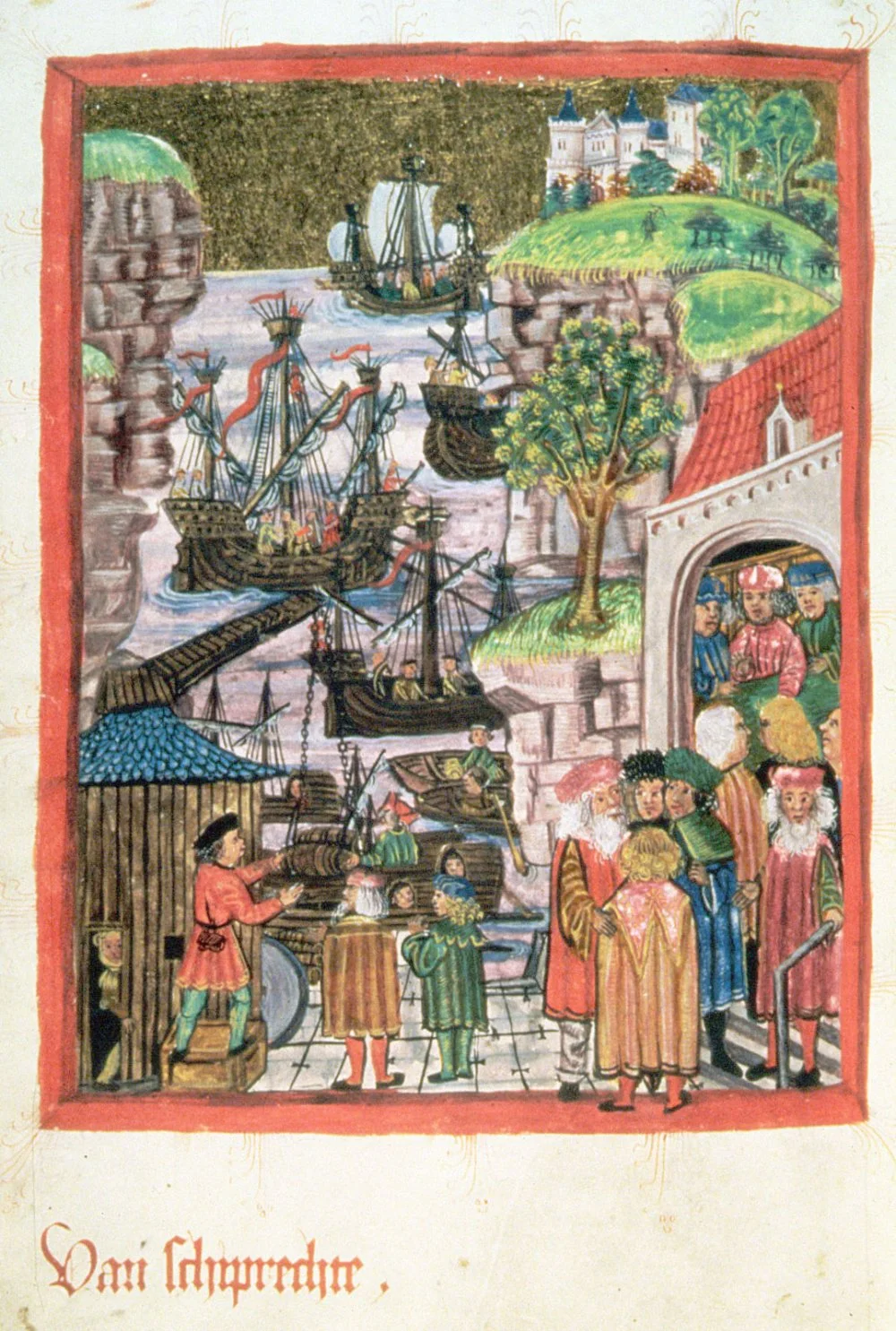

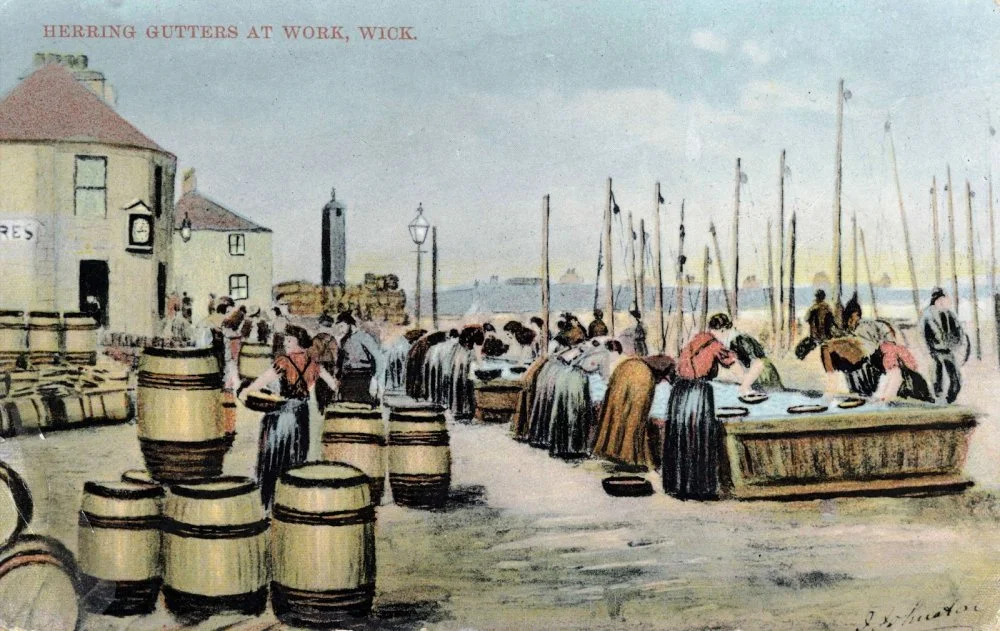

Postcard showing the herring gutters at work in Wick Harbour (Courtesy of Am Baile)

Around 1386, Buckels salted a ton of herring in barrels using this method, and the taste of this herring turned out to be heavenly! This immediately sparked a high demand for Dutch salted herring and, in turn, led to the Netherlands’ monopoly on the herring market. For centuries, the process of making maatjes remained a closely guarded Dutch (and also Flemish) secret. However, the people of Flanders (where Buckels was from) were limited by the Hanseatic League in selling the herring and could mostly use it only for personal consumption. The Netherlands, therefore, became the herring capital of the world, and the capital, Amsterdam, was ‘built on herring bones’.

The Journey of the Herrings, from a Chronicle dating to the time of Charles III, written by Jean Charetier. This supply convoy consisted of “some 300 carts and wagons, carrying crossbow shafts, cannons and cannonballs but also barrels of herring/Wikimedia commons

To this day, maatjes herring is produced in the Netherlands in accordance with the classic medieval method, which is very simple:

- The fish is prepared, gutted, and the gills and part of the guts are removed.

-

The roe is left untouched.

-

The herring is then placed in the barrels with salted water.

-

The barrels are sealed for five days.

The herring fishery in Holland. The 17th century engraving/Alamy

Having made huge sums of money through herring trade, the Dutch used the profits wisely and started building ships, and the fleets of ‘herring factories’ were the first to be built. These were large, strong ships especially designed to catch and process herring at sea. The first of these herring factory ships was built around 1415, and these ships were followed by a powerful merchant and military fleet. Herring became the main engine of expansion of the Netherlands’ colonizing powers and of the creation of the Dutch Colonial Empire.

‘The 'Royal Prince' and other Vessels at the Four Days Battle, 1–4 June 1666’ by Abraham Storck (1670)/Wikimedia commons

Of course, many tried to sabotage the Dutch monopoly, and there were several ways to get around the laws of the Hanse. For example, the competitors salted herring straight on their ships using seawater, sparing them from having to buy carefully controlled salt, and then quickly sold the fish, for example in England or France, thus avoiding Hanseatic trade posts and their monopolistic rules, according to which only the Dutch, who were union members, had the right to sell Dutch herring. The smugglers’ fish was of poor quality and often went bad as the seawater treatment was not suitable. However, it was considerably cheaper than real Dutch herring and was eagerly purchased for various needs, such as by army supply officers who were being careful with their expenses.

A section through a smokehouse showing workers smoking herring in a kipper factory, 18th century/Alamy

An Empire Built on Herring Bones

The Netherlands entered its golden age in the seventeenth century. The Dutch were on the cutting edge of trade, science, the military, and the arts. What, you ask, triggered this famous prosperity? The answer can be found in Vermeer’s View of Delft. This painting, depicting the artist’s hometown was completed in 1660, which was right in the middle of the golden age, and herring factories are clearly depicted as an integral part of the town’s landscape.

‘View of Delft’ by Johannes Vermeer (1660)/Wikimedia commons

The development of shipbuilding and increasingly busy shipyards led to the Netherlands building a strong navy. A frenzy of shipbuilding to fuel their colonial ambitions soon began in the Netherlands, and thanks to Buckels’ inventive recipe, the problem of providing the navy with good, nutritious food during long expeditions was solved. The first Dutch expeditions reached the shores of West Africa, South America and the island of Java at the end of the sixteenth century.

By the second half of the seventeenth century, the Netherlands had colonized part of the Malay archipelago and secured their position on the Malay peninsula. They had also made inroads into the island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and some regions of India, China, Vietnam, Burma, Yemen, Oman, Japan, and Newfoundland in Canada. Incidentally, they found that the herring fishing in Newfoundland was also excellent.

Illustration of the herring fishing fleet in the harbor of Amsterdam, 16th century/Alamy

The diary of a naval surgeon named James Yonge describes the work of fishing stations in Newfoundland:

If the fishing was good, the crews would head for their fishing rooms in the late afternoon, each boat carrying as many as 1,000 or 1,200 fish, weighing several tonnes all together … The shore crews began the task of making the fish right at the stage head, a combination wharf and processing plant where the fish was unloaded. A boy would lay the fish on a table for the header, who gutted and then decapitated the fish …

Peter the Great and Dutch Herring

Scientists estimate that by 1560, the total volume of herring fished in the North Sea was about 6,000 tons, and in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Dutch salted 90,000 tons of herring daily.

in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Dutch salted 90,000 tons of herring daily

Herring brought prosperity and wealth to the country. In fact, the Russian tsar Peter the Great visited Amsterdam in 1697, and he came back to his homeland astonished by the standards of living of ordinary Dutch townspeople. Thus, herring is responsible not only for the progress that Holland made but also indirectly for the reforms that Peter the Great implemented in his own country in his frantic attempts to mimic Dutch success.

In Memory of William Buckels

All these centuries later, the memory of the fisherman who invented gibbing and made the country rich has still been preserved in the Netherlands. In a church in his hometown of Biervliet (population of around 1,600 people), an image of Buckels adorns a stained glass window.

1821 lithograph copy by Hilmar Johannes Backer of a stained glass church window in Biervliet depicting Buckels at his pastime/Wikimedia commons

Herring and Early Capitalism

Building herring boats forced the Dutch to look for new technological solutions that would allow them to remain at sea for long periods of time. Shipbuilders had to build bigger boats to create the space required to house the fish processing system and the large crew required to operate it. The combination of bigger boats, a sizable crew, and technical progress lay the foundations for early Dutch capitalism.

‘Still life with herring und Bartmann’ by Georg Flegel (1679)/Wikimedia commons

Of course, the very successful Dutch experiment with herring fishing did not go unnoticed. Pirates and neighboring states sometimes attacked Dutch herring ships. In response, Dutch towns agreed to send convoys to protect their common interests, and many famous navy campaigns of the Dutch golden age were the direct result of them building the first warships to protect the herring boats.

In fact, the herring trade also helped finance the establishment of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), founded in 1602, and ensured the Netherlands’ world trade dominance during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The Conservation of Resources

In the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution brought innovations, such as steam boilers and improved methods of preservation, to the herring industry. The emergence of the railways allowed for the faster transportation of herring to domestic markets. However, by the start of the 1900s, the industry ran into some problems due to overfishing and changes to the environment.

Herring fishing in the north sea in the 19th century/Alamy

Implementing modern methods and fishing equipment, such as sonar navigation and big trawlers, improved the effectiveness of fishing but also made problems connected to overfishing worse. Soon, there was less and less herring available. At the turn of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, international treaties aimed at keeping the numbers of herring stable were signed, and the conditions included fishing quotas, seasonal restrictions, breeding, releasing young herring, and other measures aimed at preventing the fish from becoming an exotic species of the northern waters of Europe.

Herring auction in Grimsby England fish market trade (1915)/Alamy

Centuries after it was first caught for human consumption, herring still remains one of the most popular commercially fished species in the world.