Miscellaneous

Curious facts about beauty, culture and worldview of people

Special projects

RUBIES, SAPPHIRES, AND OTHER CARBUNCLES

Gems and People: A Dramatic Story of Love and Misunderstanding

~ 12 min read

THE GREAT NEEDLEWORK RACE

The History of Olympic Fashion

~ 11 min read

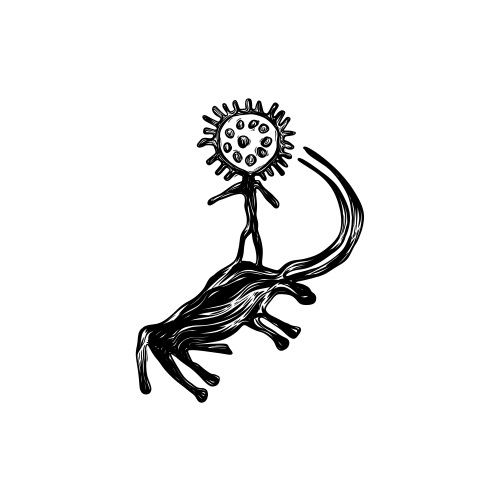

ABYLKHAN KASTEEV’S NAÏVE SOCIAL REALISM

Between the beauty of life and the power of ideology

~ 11 min read