In the Soviet Union, culture was more than art—it was a way to shape people’s minds and identities. In this interview with Qalam, Harvard University doctoral researcher Leora Eisenberg explores how Soviet cultural policy worked to sever the peoples of Central Asia from their roots, affecting areas from music and performance to the role of women, reshaping them to fit European models. This 'liberation' often came with deep personal loss, telling a story of control and what was sacrificed in the name of modernization.

From National Music to European

In the early twentieth century, neither Kazakhstan nor Uzbekistan had a tradition of polyphonic singingi

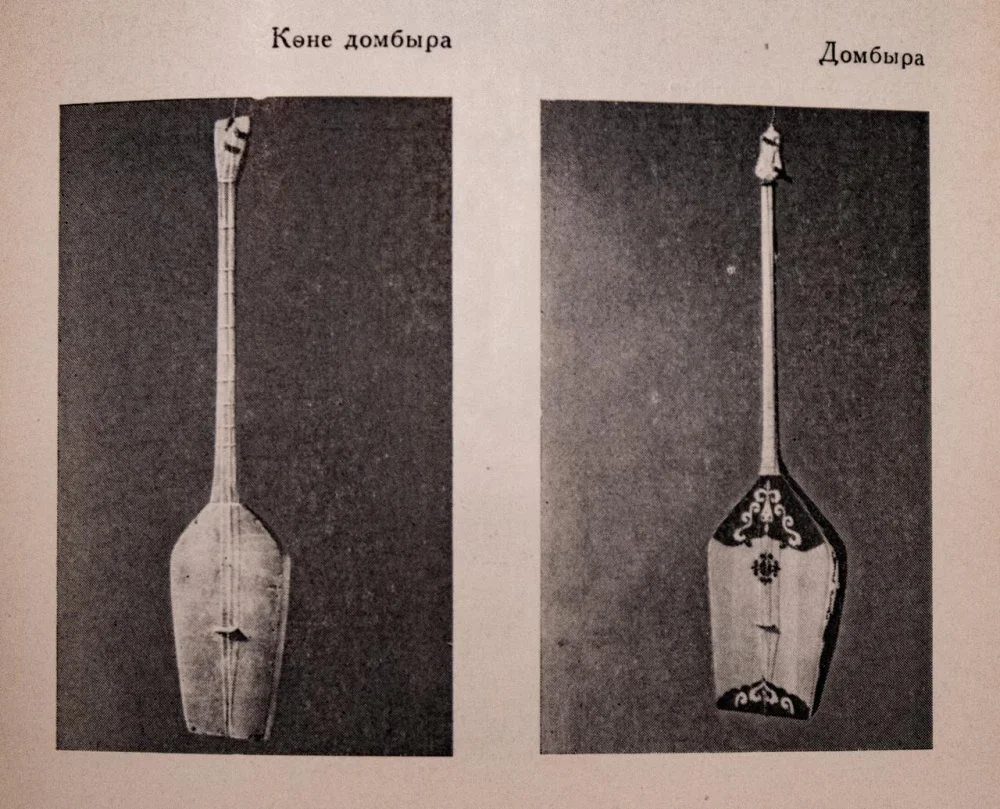

The Kazakhs had no tradition of performing indoors since performances most often took place in open spaces, and the very idea of performing in opera houses, for example, contradicted traditional Kazakh culture. Meanwhile, during the 1930s, Kazakh and Uzbek national instruments were actively modified and ‘refined’ to ensure their sound more closely resembled that of European instruments. This led to the creation of the dombyra bass, dombyra prima, dombyra tenor (corresponding to the bass, soprano, and tenor vocal classifications of European classical music), and others.

In early twentieth-century Uzbekistan, the situation was somewhat different due to the existing tradition of court performances. Historically, the territory of modern Uzbekistan was divided among three states: the Kokand and Khiva Khanates and the Emirate of Bukhara. These courts hosted performances, though these did not include polyphonic singing.

‘Remnants of the Feudal Past’ and the Asharshylyq

The attitude of the Soviet authorities toward the maqom as an Uzbek traditional art was not very favorable, and it was generally regarded as a ‘relic of feudal life’.

The situation with the Kazakh küi was different—it was received more favorably, as it was incorporated into certain operas and simply quoted in them. Yet, it is essential to understand that in the early 1930s, about 40 per cent of the Kazakh population perished due to Soviet policies. Along with them, an immense layer of culture and music disappeared, as an entire generation of küishii

The First Operas in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan

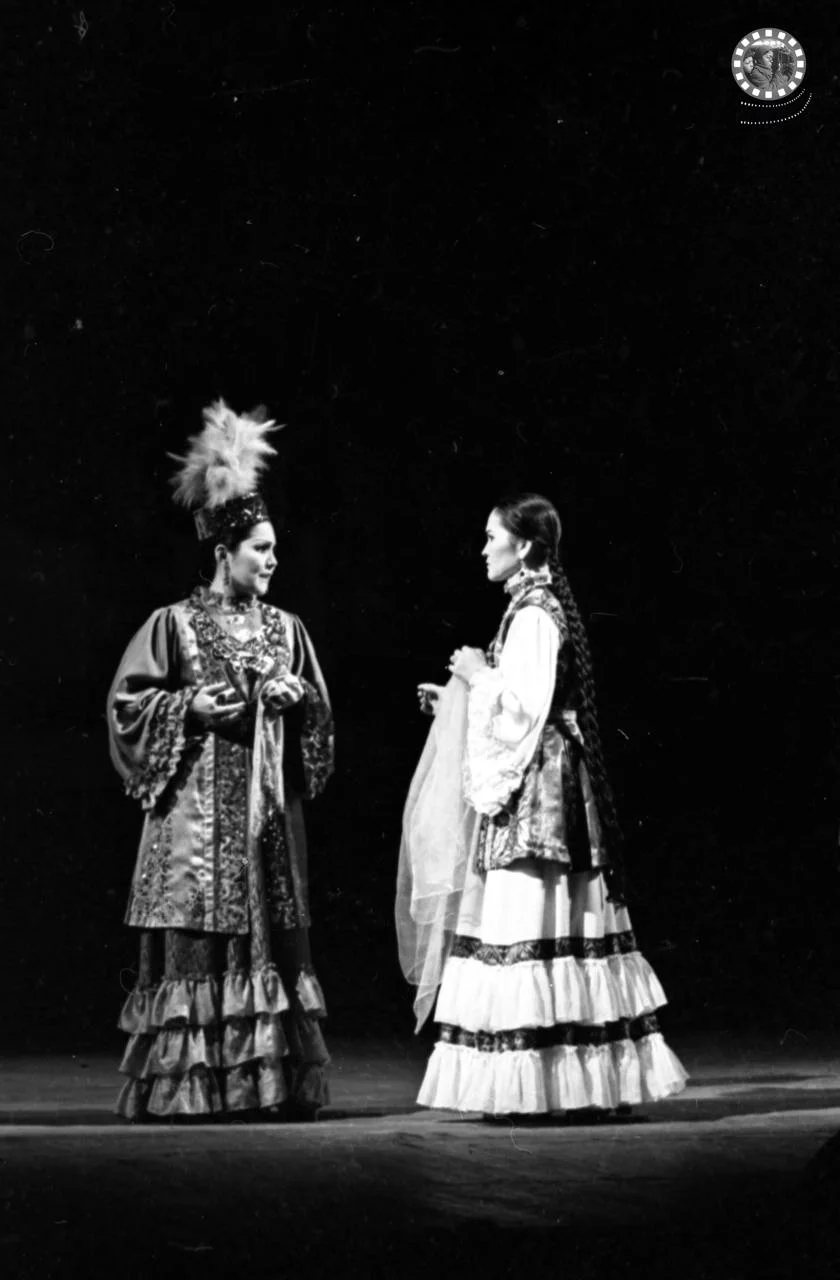

It’s important to understand that the famine in Kazakhstan had a profound impact on the cultural development of the country. There were fewer local artists left, which made it much easier for those sent from Moscow to compose symphonies. In Uzbekistan, by contrast, there were far more native artists, making it more difficult for European music to ‘break through’. For example, Yevgeny Brusilovsky, who was sent to Almaty, wrote the first Kazakh opera, Kyz Zhibek, in 1934; two years later, the work was performed during the first Decade of Kazakh Arti

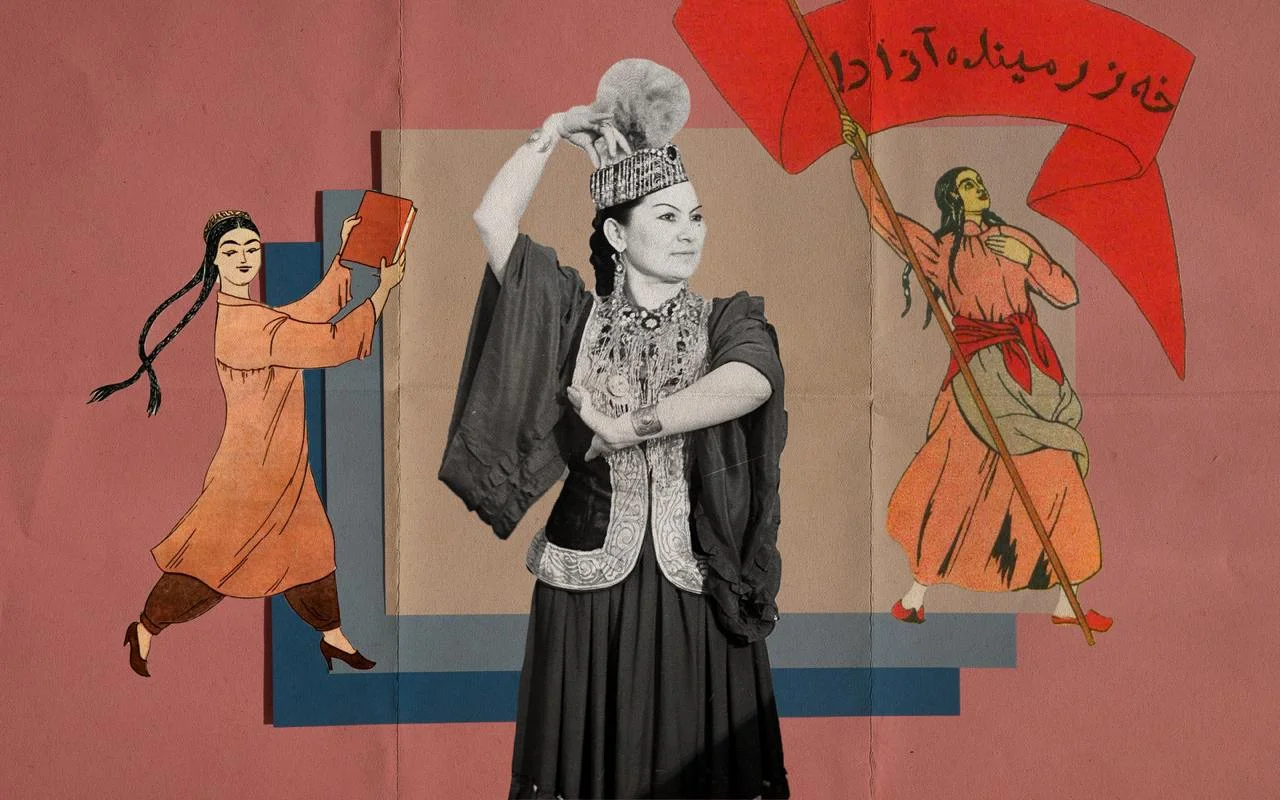

Roza Baglanova. Performance accompanied by the Kazakh folk instruments ensemble during the Decade of Kazakh Literature and Art at the Bolshoi Theatre of the USSR. 1959 / CSA CFDA RK

In Uzbekistan, the first opera did not emerge until 1939i

What Did ‘Educating the Peoples’ Mean in the USSR?

In the USSR, ‘educating the peoples’ was a form of socialist education designed to instill specific values and morals. A person was expected to be socialist ‘in content’ and national ‘in form’. This included love for the Soviet motherland, commitment to internationalism, adherence to a particular ideology, and European standards of behavior. At the same time, Soviet citizens were not supposed to forget their national culture, at least, not on an official level.

The ‘liberation’ of women was also part of this broader educational project. The Soviet authorities provided opportunities for education, for appearing in public unveiledi

The ‘Liberation’ of Eastern Women

Indeed, before the arrival and consolidation of Soviet power, women in Central Asia did not perform actively on stage. In Uzbekistan, in fact, it was outright taboo. For this reason, the Soviet authorities aimed to showcase how they had ‘liberated’ women, freeing them from the restrictions of ‘feudal life’ or the control of the bai (wealthy landowners or elite households). And precisely because of this prohibition, the first Soviet dancers and singers were often not ethnic Uzbeks, but Armenians, Bukharan Jews, and Tatars living in Uzbekistan. Many of them were already allowed to appear in public without a paranja, and their families permitted them to perform.

Of course, there were also ethnic Uzbek performers. For example, Mukarram Turgunbayeva is considered one of the first dancers in Uzbekistan and a founder of the national dance tradition. Equally well-known is Tamara Khanum, an Armenian from the Fergana Valley, and one of the first dramatic actresses in Uzbekistan, Maryam Yakubova, was a Bukharan Jew.

The Soviet authorities came and ‘granted freedom’ to women, but the local population opposed this freedom. Indeed, this is a paradox because not all of these women wanted freedom. As historian Douglas Northrop writes, the removal of the paranja was an initiative marked with blood. Women could be killed for taking it off. It is, of course, good that women in Central Asia today can wear what they want and go where they please, but we should acknowledge the great cost at which this was achieved.

One of the first Uzbek actresses, seventeen-year-old Tursunoy Saidazimova, was murdered by her own husband for ‘dishonoring’ her family. Another young performer, Nurkhon Yuldashkhojaeva, was killed by her brother for dancing in public without a chachvan, which was a rectangular mesh covering the face. In Kazakhstan, however, the social norms were somewhat different, and as a result, Kazakh women were more visibly represented on stage.

The First Decade of Kazakh Art and Literature in Moscow

The year was 1936. In Kazakhstan, the asharshylyq had only recently ended, yet there was a need to show that everything was fine in the country. This was the first goal of the Decades of Art, which were state-sponsored cultural festivals held in the Soviet Union to showcase the arts of the various republics. The second was to demonstrate how ‘the East’ had become modern, progressive, and Europeanized.

There is mention of an incident involving the members of the Kazakh delegation, who were to perform in Moscow, initially having no idea what a Decade even was. The Kazakh government was given a very short period of time to prepare—literally just a few months. That was almost no time at all, considering that singers and dancers had only recently begun performing in the European format.

There was also considerable concern, for example, about how Kulyash Bayseitova or her Uzbek colleague Halima Nasyrova would perform on stage. Would they sing correctly? Would they be able to manage? Among many cultural figures of that time, it was believed, for instance, that if a person sang using the throat, it was considered folk singingi

And most importantly, many still don’t understand the context of these Decades. Yes, it was art; yes, it was cultural policy—but it was political, above all! Every performance, painting, and costume was carefully curated to project an image of harmony, progress, and loyalty to the Soviet system. The goal was to show that Kazakhs and Uzbeks had mastered European skills both in dance and opera. And, as was often pointed out, in a very short time, they had managed to both ‘liberate’ and emancipate women, compose the first opera, and build factories. And what, they asked, had capitalism accomplished in that same amount of time?

The ‘Triumph’ of the National Language

As a rule, national performers were expected to sing in their native language. There were no Kazakh operas performed in Russian, and the same was true in Uzbekistan. It’s a paradox: people were meant to demonstrate how Europeanized they were while singing in their national language, while most likely sending their children to schools where Russian was the language of instruction. As a result, the children of these same cultural figures often spoke only Russian, even though their parents performed in their native tongue.

After all, to demonstrate how much culture is flourishing, one must sing in one’s native language. There were four key pillars of national policy: culture, language, elites, and territory. The language needed to be supported at the official level, even if, in practice, this was not actually the case.

This is only part of an interview with Leora Eisenberg on how the peoples of the USSR were ‘educated’ through culture. Watch the full version on our YouTube channel, Qalam History.