Playing asyk. Dudin S. M. Kazakhs. Kazakhstan. 1899/Wikimedia Commons

As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, a great wave of awakening surged through Kazakh intellectuals, sparking a passionate quest for knowledge. This outpouring of intellectual zeal led to an explosion of new magazines and newspapers being published in Kazakh, heralding the dawn of a new era in sharing culture. However, what these intellectuals wrote went beyond only spreading knowledge. Soon, a variety of publications emerged, covering topics like business, society, politics, art, and humor. Qalam invites you to explore snippets from Kazakh publishing culture and history, offering a glimpse into the important issues of the past.

The game of asyqi

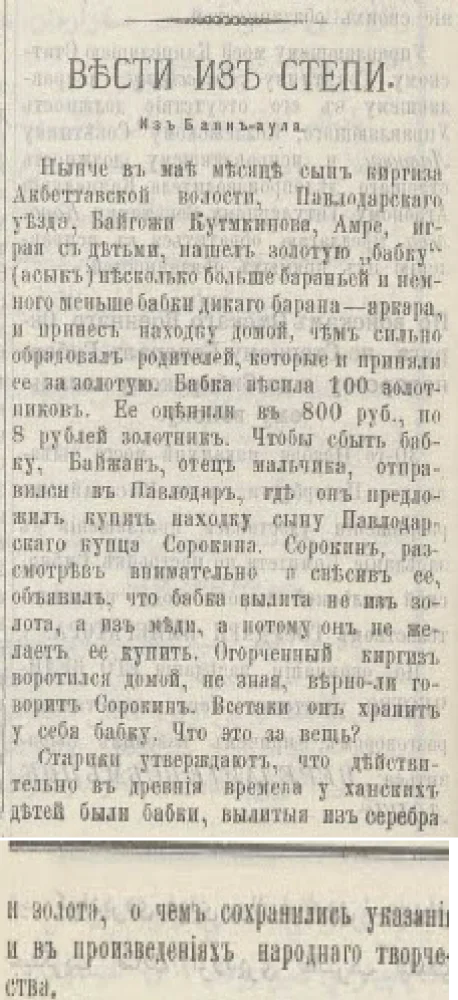

Monuments to the game are erected across Eurasia, and it is part of the official program of the World Nomad Games. The striker in this game is especially valuable, so it was sometimes weighted with lead. In well-to-do families, it could even be made of precious metals. A somewhat tragic story about how a Kazakh man found a ‘golden’ asyq is told by the Kirgizskaia stepnaia gazeta in issue No. 49 from 1894, in its regular column titled ‘News from the Steppe’.

News from the Steppe.

Bayanaul

Recently, in the month of May, Amre, the son of Baigoja Kutmukhinov, a Kyrgyz man from the Aqbettau Volost in the Pavlodar Uezd, found a golden ankle bone (asyq) while playing with other children. The bone was slightly larger than that of a sheep and slightly smaller than that of a wild mountain sheep, an argali. Amre brought the find home, much to the delight of his parents, who believed it to be made of gold. The bone weighed 100 zolotniks.i

Kirghiz Steppe Newspaper/from open sources

The Kirgizskaia Stepnaia Gazeta (In Kazakh, Dala Uälaiatynyñ Gazetі) was a special supplement to the Akmolinsk (1888–1905), Semipalatinsk (1894–1905), and Semirechensk (1894–1901) regional gazettes. It was published in Omsk in Russian with additional content in Kazakh.