The cover of the novel Krut'/From open access

Viktor Pelevin's novels are released like clockwork—annually either at the end of summer or the beginning of autumn, and 2024 was no exception. His new book, Krut', was published in Russia (and on LitRes) on 30 October and will soon be available in Kazakhstan. Though the novel's events take place in a distant future, the questions it raises are eternal and/or highly relevant. Among many other topics, Krut' delves into the clash between feminism and traditionalism, the flourishing prison culture in Russia, the ‘new Middle Ages’, and the war-like mentality prevalent in the world today. Qalam read Krut' and shares its impressions.

Invariably, the action in Pelevin's latest book takes place in a world of (well, practically) victorious globalization, where the elites have achieved immortality in virtual reality, while natural reality has long since become something like a run-down suburb on the outskirts of a megapolis. Everything is ruled by a corporation called Transhumanism INC, which provides eternal life services. One of its security officers, Markus Sorgenfrey—familiar to readers from Journey to Eleusis (2023)—returns to this world. Once again, this virtual special agent must save a world teetering on the brink of an apocalypse. The primordial spirit of war, embodied by Achilles, prepares to manifest in human form to conquer Earth and establish his own rule.

The cover of Pelevin's book "Journey to Eleusis"/From open access

Soon, Sorgenfrey and his superior, Admiral-Bishop Lomas, discover that the demon's accomplice should be sought in a penitentiary in northern Siberia. They then learn that the world's fate depends on the feminist avenger Varvara Zugunder. The catch is that Zugunder has been believed to be dead for several hundred years. Apparently, the legendary ‘femme’ was buried prematurely, and Sorgenfrey must do whatever it takes to reach her. The detective must negotiate with ideological opponents from the Good State party, a compassionate Bolshevik faction (yet another variation of totalitarianism in Russia). He must also find a lost chapter from the book of the ultra-conservative writer Sharaban-Mukhlyuev. Finally, he must investigate the story of the writer's painful romantic relationship with the feminist literary critic Rybka.

Victor Pelevin Japan. Tokyo. October 30, 2001/Vladimir Solntseva/ITAR-TASS

The dazzling wrapper of the science fiction detective plot is not an end in itself. In the apocalyptic kaleidoscope of Krut', almost everything is twisted into the mix—from the age of the dinosaurs, the Iliad, and Christianity to an unappealing totalitarian-capitalist future. The protagonist is an observer with nearly limitless capabilities, a ‘relatively living’ camera that captures the sweeping authorial myth (or cycle of myths).

Sandro Botticelli: Venus and Mars circa 1483/The National Gallery, London/Wikimedia Commons

One of the novel's first revelations is that hell exists—and in the past, it was physically located on Earth. The source of this information is dubious: it comes from the nuncio of the Roman Mama (feminism, we’re reminded, has triumphed), Mother Lucilia, who warns Lomas and Sorgenfrey of an impending catastrophe. In a vision granted to her sisters in faith, hell was revealed—not in a traditional form, though: ‘It resembled humid, hot jungles, smelling of decay and rot. And its inhabitants looked indistinguishable from ancient reptiles.’ Following this, Jesus Christ descends into hell and destroys it. The Son of God appears in the form of . . . a meteorite. In this reinterpretation, Earth's hell is the Mesozoic era, portrayed as a space of continuous mutual devouring, survival struggle, and reproduction. The spirit of Achilles, who seeks revenge, is the former ruler of this ‘pleasant’ domain.

In Krut', Pelevin argues that beyond subjective evil, there is absolute evil.

Embedded in the structure of the world itself, a particular way of perceiving it and a model of interacting with reality. When these elements activate, evil awakens and begins to spread. The pact between Achilles’ spirit and a man includes a condition—the latter becomes almost immortal but must choose a single opponent capable of killing him. For the famous ancient Greek warrior, the fatal enemy was ‘the one who would cuckold the Spartan king’. If the hero dies, the spirit will transfer to the killer.

Here, Pelevin also ingeniously rewrites Homer. The Trojan horse was supposedly a sculpture of a dinosaur, which the demon Achilles created in the likeness of his former body. Paris, Helen, and Menelaus work together in alliance with the ancient Sufis. The betrayal and the Trojan War were explicitly staged to neutralize the demon, imprisoning him in a prison—the body of Paris, who had been trained in spiritual practices. In Pelevin's version of the Iliad, Paris, not a warrior but a lover, becomes the central hero.

The Judgement of Paris (c. 1485–1488) by Sandro Botticelli/Palazzo Cini Gallery, Venice/Wikimedia Commons

The war demon’s shift from being the defeated to the victor illustrates how effortlessly a savior can become a tyrant and a victim an aggressor. Warfare is infectious, and evil spreads like a virus, establishing its own framework within the very person who once fought against it or was its victim.

This theme becomes the foundation of yet another distinctly mythological plot, set this time in the futuristic world envisioned by Sorgenfrey. Pelevin intertwines two relevant topics, one global (feminism) and one local (prison culture). Russia’s public sphere and everyday life are heavily influenced by criminal subculture, and boldly, the writer flips the established hierarchy. In this ‘bright future’, citizens (apparently globally) have been implanted with chips. Artificial intelligence has managed to ‘correct displays of toxic masculinity at the cerebral level’. As a result, women have become the dominant gender, and any woman can easily take down a male bodybuilder with little effort.

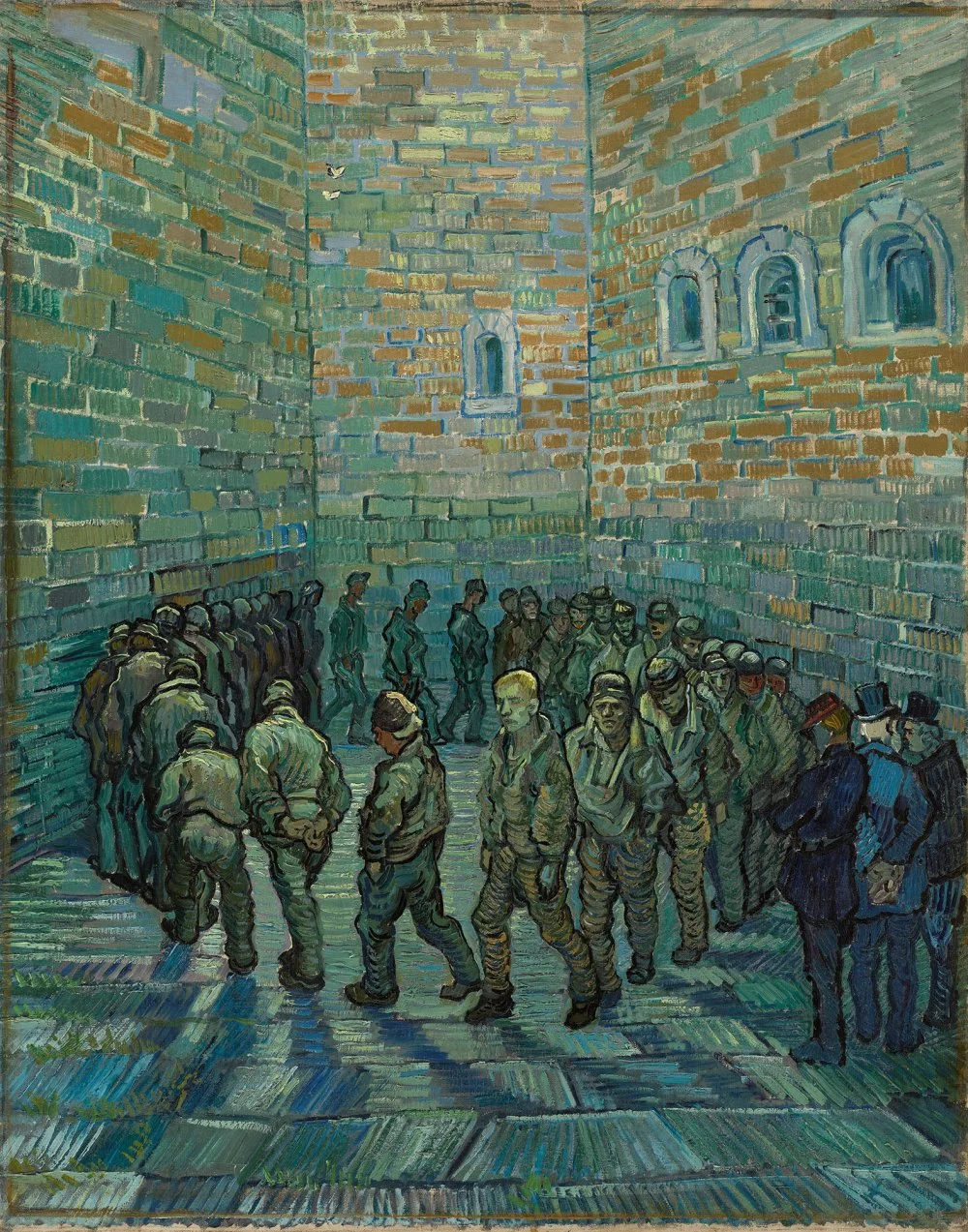

In the prison environment, this led to the rapid rise of the ‘roosters’,i

Prisoners Exercising by Vincent van Gogh (1890) / The Prison Courtyard, also known as Prisoners' Round/Wikimedia Commons

However, their life in prison is not without challenges—among the incarcerated women are ‘femme shankers’, who kill men (preferably the roosters) using sharpened neuro-strap-ons. ‘Virtually all the high-ranking hens in the criminal hierarchy of Dobrosud are shankers,’ Pelevin explains. Outside of the prisons, though, men in this ‘brave new world’ cannot feel safe either. Some of the most radical feminists practice pyking, or gender-based killings using phallic-shaped cold weapons, named after the famed feminist Zugunder. She is believed to have committed ninety-six gender-based murders in the course of ‘her struggle’.

In the universe of Krut', the oppression of former oppressors is a common occurrence. Once the last becomes the first, they quickly begin to replicate the very behaviors they once suffered under. The awareness of the injustice perpetuated by the social hierarchy is quickly forgotten when one reaches the top. The roles of oppressor and victim are exchanged with theatrical ease (the conflict between Kuker and the ‘fema prisoner’ Daria Troedyrkina is a striking example). Meanwhile, the infrastructure of evil only grows stronger, spreading like a virus with the speed of Omicron.

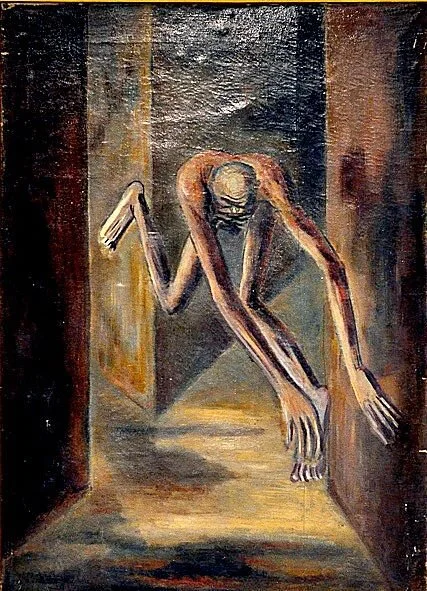

In Pelevin’s novel, the criminal underworld and radicals thirsting for ‘righteous’ vengeance resemble a reincarnation of the reptilian era. A thin veneer of high technology barely covers the eternal Mesozoic era. ‘He wanted to merge with the great power he felt when he became part of the Mesozoic world. He stood before existence not as a crab, but as a dinosaur, and in this improvised ritual, like in the dance of a Theban hoplite, the fiery calls of Eros and the icy breath of death intertwined,’ Pelevin writes to describe Kuker’s feelings while inside the simulation of a prehistoric world. The fertile ground for evil is total vulnerability to death, which follows a being like a shadow, threatening to consume it at any moment. Aggression activates the fear of death, which, in turn, strengthens aggression—an eternal engine fueled by human vulnerability and the promise of power. It is precisely these conditions that the spirit of Achilles exploits as he seeks a new victim.

Boris Gololosov. A man bangs his head against a wall (Psychological plot). 1936–1937/tretyakovgallery.ru

The narrative unfolds slowly. The first half of Krut' feels like an overly drawn-out prologue. Then, the story of the difficult romance between Sharaban-Mukhlyuev and Rybka begins. At this point, the novel comes alive, lifting off the ground and taking the reader, who by now had probably lost hope of soaring, with it. This final and central myth of the book is ‘warm-blooded’—vividly contradictory. Delightfully absurd Zoom-attacks by the naked Sharaban-Mukhlyuev on Rybka’s pseudo-liberal interlocutors alternate with finely described psychological violence. After the monologue of this highly dubious narrator, we get Sorgenfrey’s commentary, in which we hear the author’s voice, which is unusually direct and endearingly candid. And in the second half of Krut', Pelevin manipulates the reader like a master puppeteer.

Pouring out his soul, Sharaban-Mukhlyuev reflects on neo-barbarism, though, at times, it seems he detects its traces in himself but quickly dismisses the uncomfortable thought. He writes about a Roman basilica where a tribal chief sits. ‘The hun’s intestine, celebrating the triumph of heading nature’s call on the Roman Forum, wrapped in a requisitioned toga. This is the New Middle Ages greeting us everywhere.’ Here, he speaks of the suppression and assimilation of meaning by an alien force, which leads to a mismatch between form and content. This results in the inevitable distortion of communication, an inherent attribute of war, where the genuine essence of subjects is replaced by images of ‘us’ and ‘enemies’. War is the stripping of life down to the mechanics of survival, a form of anti-communication like ignoring a conversation partner. Its constant companion, the noise of disinformation, is an illusion that masks the deafening silence of the inability to engage in dialogue.

Embrace by Pablo Ruiz Picasso (1900/) Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts

The dramatic romance between the ideological enemies Sharaban-Mukhlyuev and Rybka, which deliberately adopts BDSM themes, is compelling due to its confrontation between love and war. Pelevin cleverly ‘barbarizes’ The Master and Margarita: the heroine embroiders a cap for her ‘beloved’ with the letter M (for misogynist). ‘In general, there was a wall of mutual misunderstanding between Ry and me,’ the ‘master’ confesses. This inability to accept one another and truly connect, as revealed in the confession, leads to an increasing communication distortion. A striking metaphor for this is the writer's muddled safeword—Yanagihara—which results in a ‘catastrophe’ and yet another instance of the victim replicating the aggressor's behavior.

‘The engineer of human souls is someone capable of understanding that there is no one on our planet except for the suffering … What should the engineer do? Help me learn to love people again,’ Marcus Sorgenfrey says as he reflects on Sharaban-Mukhlyuev's professional failure.

But above all, it is a struggle not against an ‘enemy’ but against the very infrastructure of evil—the need to stop the spread of the virus in one’s own space. ‘Under our feet was not solid ground but a black hole covered in sand. But this could only be understood by closing one’s eyes and listening to the silence … “Yanagihara!”—a trembling female voice screamed in my head. “Yanagihara!”—and it seemed these were no longer the words of Special Agent Sorgenfrey. Moreover, they did not seem to come from an imagined future. They were too loud. And far too close.’