Friedrich Engels believed that labor created humans, but modern scientists argue that love, children's curiosity, and long-distance running played a much more significant role in the formation and development of our species. In his lecture series for Qalam, paleontologist Alexander Markov explains how and why Homo sapiens emerged.

Most hypotheses about the pathways and mechanisms of human evolution traditionally revolve around two unique human traits: a large brain and the complex use of tools. However, some leading specialists, most notably Owen Lovejoy, argue that the key to understanding our origins lies not in our enlarged brains or how we used stone tools (because these traits appeared relatively late in hominid evolution) but in other unique characteristics of the ‘human’ evolutionary line related to sexual behavior, family relationships, and social organization. Lovejoy advocated this viewpoint as early as the 1980s, and at that time, he proposed that a pivotal event in early hominid evolution was the transition to monogamy, i.e., the formation of stable marital pairs. This hypothesis has, however, been challenged, revised, confirmed, and refuted many times since.

Neanderthal man feasting on their kill during prehistoric times. From L'Homme Primitif, published 1870/Alamy

New data on Ardipithecus have strengthened the arguments supporting this idea. The study of Ardipithecus had revealed that chimpanzees and gorillas are not the best models for reconstructing the mindset and behavior of our ancestors. While Lucy remained the most ancient and well-studied hominid, it was still possible to assume that the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees was generally similar to a chimpanzee. But Ardi fundamentally changed this perspective. It became clear that many traits of chimpanzees and gorillas are relatively recent, specialized characteristics of these relict primates—our human ancestors did not have these traits. If this holds true for legs, arms, and teeth, it may also be true for behavior and family relationships. Therefore, we should not assume that the social life of our ancestors was like that of modern chimpanzees. By setting chimpanzees aside, we can focus on the information provided by fossil records.

TEETH AND KINDNESS

It is significant that male Ardipithecus, as mentioned earlier, did not have large canines that, like other apes, could serve as weapons and a means of intimidating male competitors. The reduction of the canines in later hominids—Australopithecus and humans—was once interpreted either as a byproduct of the enlargement of molars (back teeth) or as a result of the development of the stone tool industry, which made this natural weapon unnecessary. However, findings from recent decades have shown that the canines began to shrink long before the production of stone tools and before the molars of Australopithecus increased in size (likely due to their final adaptation to the savanna and the inclusion of tough root vegetables in their diet). As a result, the hypothesis that social factors led to the reduction of canines has gained more credibility. Large canines in male primates are a reliable indicator of intraspecies aggression. Therefore, their reduction in early hominids likely indicates that relationships between males became more tolerant. They began to fight less with each other over females and dominance within the group.

Skulls of orangutan and human, Indonesia. Displayed in information center of tanjung putting national park for comparison/Alamy

In great apes, reproductive success (the number of offspring that survive to adulthood, a concept closely related to Darwinian ‘fitness’) depends less on fertility and more on the survival of the offspring. Great apes have a prolonged childhood, and females invest a tremendous amount of energy and time in raising each offspring. While a female is nursing, she cannot conceive. As a result, males are constantly faced with a lack of females who are ready to mate. Chimpanzees and gorillas solve this problem by force. Male chimpanzees form raiding parties and invade the territories of neighboring groups, trying to expand their domain and gain access to new females. Gorilla males drive out potential competitors from the family and strive to become the sole ruler of the harem. For both species, large canines are not a luxury but a tool for leaving more offspring. So why then did early hominids give them up?

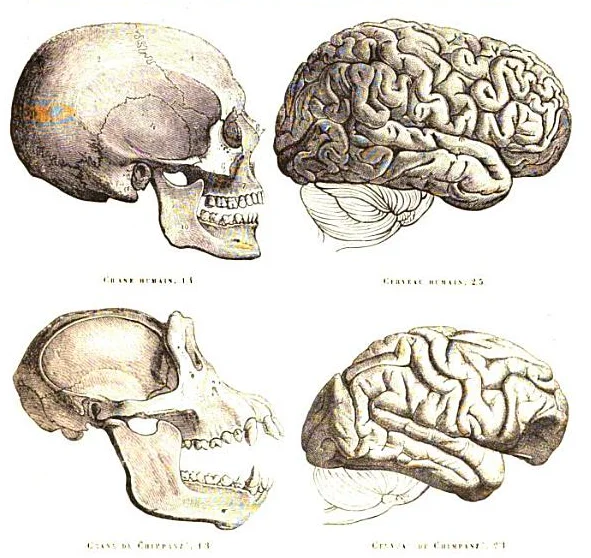

Human and chimpanzee skull and brain/Wikimedia Commons

Another critical component of the reproductive strategy in many primates is ‘sperm competition’. When a female mates with multiple males in succession, their sperm competes to fertilize her egg, leading to the development of corresponding adaptations in males. Sperm competition is characteristic of species that practice open mating systems within groups containing many males and females. Large testes are a reliable indicator of sperm competition. Gorillas, with their well-guarded harems, and solitary orangutans (also staunch polygamists, although their mates usually live separately rather than in a single group) have small testes, as do humans. In contrast, sexually liberated chimpanzees have enormous testes. Other key indicators include the speed of sperm production, sperm concentration, and the presence of specific proteins in the semen that create barriers to foreign sperm. Based on the combination of all these traits, we can conclude that while sperm competition once played a role in human evolutionary history, it has long ceased to be significant.

If early hominid males did not fight each other over females and did not engage in sperm competition, they must have found another way to ensure reproductive success. While uncommon in the mammalian world, this approach, the establishment of monogamous partnerships, proved effective. Such pairings, observed in merely 5% of mammalian species, involve the creation of stable family units. In these monogamous arrangements, male partners typically take on significant responsibilities in nurturing and raising their young.

SEX IN EXCHANGE FOR FOOD

Lovejoy suggests that monogamy might have evolved from behaviors observed in some primates, including chimpanzees. This refers to "mutually beneficial cooperation" between the sexes based on the principle of "sex in exchange for food." Such behavior could have developed in early hominids due to the specifics of their diet. Ardipithecus were omnivores, gathering food both in trees and on the ground, and their diet was much more diverse than that of chimpanzees and gorillas. It's important to note that omnivory is not synonymous with indiscriminate eating among primates—quite the opposite; it involves high selectivity, a hierarchy of food preferences, and the increased attractiveness of specific rare and valuable food resources. Gorillas, who feed on leaves and fruits, can afford to lazily wander through the forest, covering only a few hundred meters a day. Omnivorous Ardipithecus had to be more active, traveling much greater distances to find something tasty. This, in turn, increased the risk of falling prey to predators.

A female mountain gorilla with her young baby, they are a part of a group of the rare Mountain Gorillas (gorilla beringei beringei) in Volcanoes National Park in the Virunga Mountains/Getty Images

In such conditions, the "sex in exchange for food" strategy became very advantageous for females. Males who provided food to females also improved their reproductive success, as their offspring had a better chance of survival.

If the males of ancient hominids adopted the habit of bringing food to females, specific adaptations would have evolved over time to facilitate this behavior. In many intelligent animals, including primates, biological (genetic) evolution is guided by culture. Primates do not have instincts in the strict sense (complex yet entirely innate behaviors). Therefore, when we say that a new behavior emerged among them (in this case, "males adopted the habit of bringing food to females"), we always imply that this behavior initially arose as a cultural tradition. That is, it was preserved through cultural, not genetic inheritance—passed down not through genes but through social learning* (which refers to acquiring knowledge and skills from others, for example, by copying the actions of others, as opposed to learning through personal experience). The new custom, in turn, altered the environment to which individuals constantly adapt through natural selection. Thus, culture (in this case, the custom of feeding females) changed the direction of selection, now favoring genes that contributed to the development of traits in males that enhanced their fitness in a society where it was customary for males to feed females. In other words, the cultural tradition of feeding females led, through changes in natural selection, to genetically driven changes in the body (legs, arms, teeth, brain...), helping males survive and reproduce more successfully in conditions where they fed females.

The food they gathered had to be carried over long distances. This is difficult to do when walking on all fours. It is possible that bipedalism—the most distinctive trait of hominids—developed precisely in connection with the custom of supplying females with food. The use of primitive tools (such as sticks) to extract hard-to-reach food items could have provided additional motivation.

Drawing that recreates the lifestyle of Java Man/Alamy

The changing behavior must have also influenced the nature of social relationships within the group. The female was now interested in ensuring the male didn't abandon her, and the male was concerned that the female would remain faithful. Both goals were hindered by the typical behavior of primate females, who "advertised" ovulation or the time when they were able to conceive. Such advertisement is advantageous in societies like those of chimpanzees, where there are almost no permanent pairs, no paternal care of offspring, and the female mates with many males during ovulation. However, in a society where stable pair bonds predominate, built on the "sex in exchange for food" strategy, a female has no interest in making her male endure long periods of abstinence (he might stop providing food or even leave for another, the scoundrel!). Furthermore, it benefits the female if the male cannot determine when conception is possible at all. Many mammals can detect this through smell, but natural selection favored the reduction of many olfactory receptors in hominids. Males with a diminished sense of smell fed their family better—and thus became more desirable partners.

Prehistoric man - inhabitants of northern France 250,000 years ago. Remains found near modern day town of Chelles/Photo by Culture Club/Getty

Additionally, the male had no interest in his female advertising her fertility and stirring up unnecessary attention from other males, especially if he was "out hunting." Females who concealed ovulation became more preferred partners because they gave fewer reasons for infidelity.

Emmanuel Benner. Prehistoric Hunt. 1892/Wikimedia Commons

As a result, hominid females lost all external signs indicating their readiness (or lack thereof) for conception.i

WHY WOMEN PREFER CARING MEN

As pair bonds strengthened, female preferences likely shifted from the most aggressive and dominant males to the most nurturing ones. In species where males do not care for the family, choosing the most dominant (strong and masculine) male is often the best strategy for the female. However, paternal care of offspring fundamentally changes this dynamic. Now, it is much more critical for the female (and her offspring) that the male is a reliable provider. Traits of masculinity and aggressiveness, such as large canine teeth, begin to repel rather than attract females. A male with large canines is more likely to enhance his reproductive success through force and fighting other males. Such "tough" husbands fall out of favor when the survival of offspring depends on having a diligent and dependable provider. Females who choose aggressive males raise fewer offspring compared to those who select non-aggressive, hard-working males. As a result, females start to prefer males with smaller canines, and sexual selection leads to canines quickly decreasing in size.

As a result, our ancestors formed a society with reduced levels of intra-group aggression. This created the conditions for the development of cooperation and mutual assistance. The reduction of antagonism among females allowed them to cooperate in the joint care of offspring. The reduction of antagonism among males facilitated the organization of joint raids for food gathering. Chimpanzees also occasionally practice collective hunting, as well as collective warfare against neighboring groups of chimpanzees. Among early hominids, this behavior likely developed to a much greater extent. This opened new ecological opportunities for hominids. Valuable food resources that were impossible or extremely dangerous to acquire alone (or in small, poorly organized groups that could scatter at any moment) suddenly became accessible when hominid males learned to unite in cohesive groups where each member could rely on his comrades.

From here, it is not difficult to deduce the subsequent adaptation of Ardipithecus descendants to entirely new types of resources — including the transition to scavenging in the savannah (which was undoubtedly very risky, requiring a high level of male cooperation, as competition for carcasses of large animals in the Pleistocene African savannah was fierce) and eventually to collective hunting of large game.

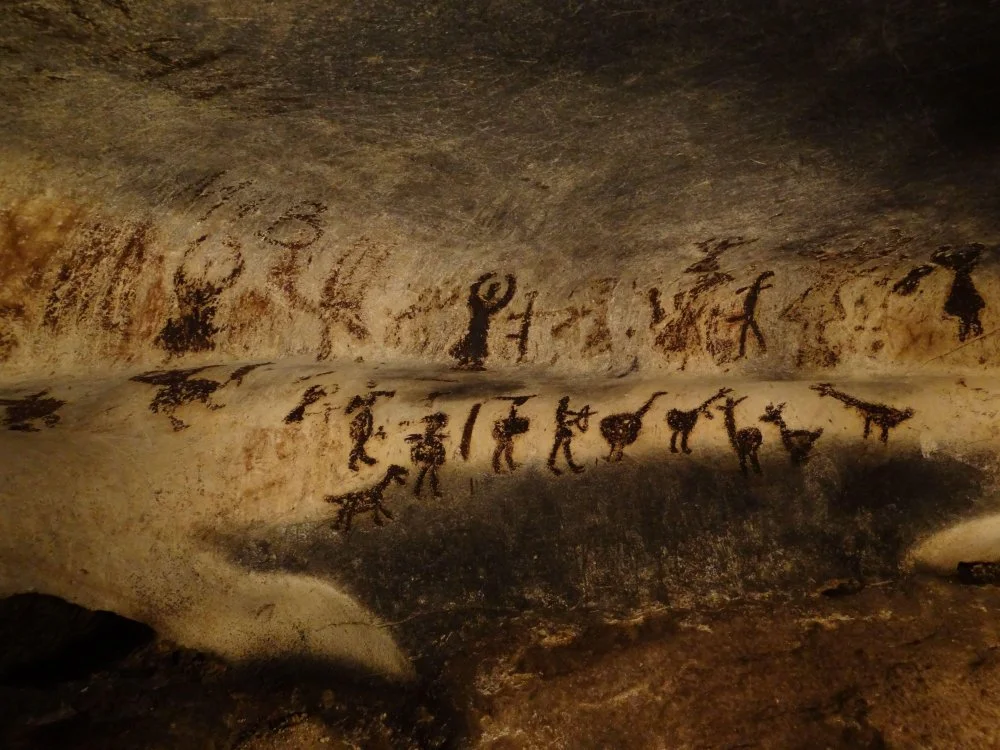

Prehistoric art wall painting in neolithic cave Magura, Bulgaria/Alamy

In this theory, the subsequent brain expansion and the development of the stone tool industry appear as secondary — and even somewhat accidental — consequences of the specialization path that early hominids followed. The ancestors of chimpanzees and gorillas had the same initial potential, but they took a different evolutionary route: they relied on force to solve mating issues, which kept their intra-group antagonism high and their level of cooperation low. Complex tasks requiring coordinated actions of united and friendly groups remained beyond their reach, and as a result, these apes never developed intelligence. Hominids "chose" an unconventional solution — monogamy, a relatively rare strategy among mammals — and this ultimately led them to the development of intelligence.

Lovejoy's theory unites three unique features of hominids: bipedalism, small canines, and concealed ovulation. Its main strength lies precisely in providing a unified explanation for these three traits rather than seeking separate causes for each one.

Emmanuel Benner. Lakeside Dwelling. 1878/Wikimedia Commons

Lovejoy’s hypothesis has been around for 40 years. All its components have long been actively debated in scientific literature, supported by a wealth of facts, not just the basic ideas we can discuss in a popular lecture. New data on Ardipithecus have "aligned" well with Lovejoy’s theory, allowing for clarification of its details.

BE LIKE CHILDREN

We’ve already mentioned that the reduction of canines in early hominid males can be viewed as "feminization." Indeed, the reduction of one of the typical "male" traits in apes made male hominids more similar to females. This may have been related to a decreased production of male sex hormones or a reduced sensitivity of certain tissues to these hormones.

Look at orangutans and gorillas in a zoo. You don’t need to be a biologist to notice how much more the females of these species resemble humans compared to the males. A mature male orangutan or gorilla can look intimidating, draped in secondary sexual characteristics that display masculinity and strength: a humped silverback, a fierce gaze, enormous pancake-like cheeks, and massive folds of black skin on the chest. There’s little that’s human-like in them. But their females are pretty appealing.

Beyond feminization, there was another significant trend in the evolution of our ancestors. Regarding skull shape, hair structure, jaw size, and teeth, humans resemble juvenile apes more than adults. Many of us retain curiosity and playfulness—traits typical of most mammals only in childhood, while adult animals are usually sullen and uncurious. This is why anthropologists believe that neoteny, or juvenilization—the delayed development of specific traits, leading to the retention of juvenile characteristics in adult animals—played an essential role in human evolution.

Juvenilization may have also contributed to the transition to monogamy. For family pairs to become even somewhat stable, partners need to feel a special bond toward each other and form mutual attachment. In evolution, new traits rarely arise from nowhere; typically, some old trait is repurposed and modified through selection. The most suitable "prototype" (preadaptation) for forming strong marital bonds is the emotional connection between mother and child. Studies of monogamous and polygamous mammal species suggest that systems for forming strong family ties have repeatedly evolved based on the older system of emotional bonding between mothers and their offspring.

Infant Mountain Gorilla kissing Silverback male. Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda, Africa/Getty Images

The ability to transfer behaviors developed for interactions with children onto other social partners could have played an important role in human evolution. It’s possible that the juvenilization of the appearance and behavior of adult hominids was supported by selection because individuals with childlike traits elicited more tender feelings from their partners. This could have increased their reproductive success if wives were less likely to cheat on such husbands (who were likely also less aggressive and more dependable), and husbands were less likely to leave wives who looked like young girls, signaling their need for protection and support. While this is just a hypothesis, some indirect arguments can be made in its favor.

If juvenilization played a role in the evolution of human thinking and behavior, something similar might have occurred in the evolution of our closest relatives—the chimpanzees and bonobos. These two species differ in their temperament, behavior, and social organization. Chimpanzees are fairly sullen, aggressive, and warlike, with males dominating their groups. Bonobos, on the other hand, live in more resource-rich environments than chimpanzees. This may be why they are more carefree, good-natured, and quicker to reconcile with females who are better able to cooperate and hold more "political" power in the group. Moreover, the skull structure of bonobos, like that of humans, shows signs of juvenilization. Perhaps we could find similar traits in bonobo behavior as well?

American anthropologists from Harvard University and Duke University decided to test whether chimpanzees and bonobos differ in the chronology of the development of certain cognitive and behavioral traits related to social life. To do this, they conducted three series of experiments with semi-wild chimpanzees and bonobos living in special "sanctuaries," one located on the northern bank of the Congo (home to chimpanzees) and the other on the southern bank, in the territory of bonobos.

In the first series of experiments, pairs of monkeys were released into a room where there was something tasty. The pairs were formed so that the monkeys were approximately the same age, and there was a roughly equal number of same-sex and opposite-sex pairs. Three types of treats were used, differing in how easy they were to monopolize (some were easier to claim entirely, while others were more difficult). Researchers observed whether the monkeys would share the food or if one would take it all for themselves.

It turned out that young chimpanzees and bonobos were equally willing to share food with their companions. However, as they aged, chimpanzees became more selfish, while this did not happen with bonobos. Thus, bonobos retain a "childlike" trait—lack of greed—into adulthood.

Bonobos initiated games, including sexual ones, more often than chimpanzees. Playfulness decreased with age in both species, but this happened more quickly in chimpanzees than in bonobos. Therefore, in this respect, bonobos also behave in a more "childlike" manner compared to chimpanzees.

Bonobo juveniles hugging each other. Lola Ya Bonobo Sanctuary, Democratic Republic of Congo. Oct 2010/Getty Images

In the second series of experiments, the monkeys were tested for their ability to refrain from pointless actions in a specific social context. Three people stood shoulder to shoulder in front of the monkey. Two of the people on the ends took a treat from a container that was inaccessible to the monkey, while the person in the middle took nothing. Then, all three extended their fists toward the monkey so it wasn’t visible who had the treat. The monkey could request food from any of the three. The monkey was considered to have solved the task correctly if it only asked the two people who had taken the treat and ignored the person in the middle.

It was found that chimpanzees, as early as the age of three, handle this task very well and retain this ability for life. Young bonobos, on the other hand, often "made mistakes" and requested food from all three people. Only by the age of 5–6 do bonobos catch up with chimpanzees in terms of the frequency of correct decisions. Thus, in this case, we can also talk about a developmental delay in bonobos compared to chimpanzees. Of course, this is not about mental retardation.

Bonobos are not less intelligent than chimpanzees; they are simply more carefree and have a less strict social life.

In the third series of experiments, the monkeys were given a more complex task—to adapt to a change in human behavior. They had to ask one of two experimenters for food. During the preliminary tests, one of the experimenters always gave the monkey a treat, while the other never did. Naturally, the monkey became accustomed to this and began to consistently choose the "kind" experimenter. Then, the roles were suddenly reversed: the kind experimenter became stingy, and vice versa. The scientists observed how quickly the monkey would realize what had happened and adjust its behavior accordingly. The results were similar to those from the previous series of experiments. Starting at around five years old, chimpanzees quickly adapted and began choosing the experimenter who was currently giving them food rather than the one who had done so in the past. Young bonobos performed worse on this task and only caught up with the chimpanzees by the age of 10–12.

These results align well with the hypothesis that bonobos exhibit a developmental delay (juvenilization) of certain mental traits compared to chimpanzees. This may be due to the lower levels of intraspecies aggression in bonobos, which in turn could be related to the fact that bonobos live in more resource-abundant areas and face less intense competition for food.

Bonobo baby Kasai climbs in the Zoo Leipzig, Germany, 27 November 2013. The baby born in January grows up quickly and attracts many visitors/ZB/Hendrik Schmidt/picture alliance via Getty Images

Interestingly, artificial selection for reduced aggression during domestication in some mammals has led to the juvenilization of certain traits. For example, in the famous experiments by D.K. Belyaev and his colleagues on the domestication of foxes, animals were selected for reduced aggression. As a result, friendly animals were obtained, and some "childlike" traits, such as floppy ears and shortened snouts, persisted into adulthood. It seems that selection for friendliness (which is a "childlike" trait in many animals) may have the side effect of juvenilizing certain other aspects of morphology, cognition, and behavior. These traits may be interconnected—possibly through hormonal regulation.

We cannot yet say for sure how relevant the selection for reduced aggression was in our ancestors or whether our juvenile traits (such as a high forehead, shortened facial structure, characteristic hair patterns, and curiosity) can be explained by such selection. But the hypothesis seems plausible. A reduction in inter-group aggression likely played an important role in the early stages of hominid evolution.

Bonobos feeding on palm nuts. Lola Ya Bonobo Santuary, Democratic Republic of Congo. Oct 2010/Getty Images

WHAT DOES LONG-DISTANCE RUNNING HAVE TO DO WITH IT?

Let’s consider another example of how cultural adaptations—valuable skills and behaviors passed on through social learning—could have influenced the biological evolution of our ancestors. This concerns long-distance running. After all, our ancestors not only started walking on two legs but also became quite good at running on them.

In short-distance running, humans fall far behind many mammals. The best human sprinters can run at a speed of 10 m/s for about 20 seconds. By comparison, a Thomson's gazelle accelerates to 26.5 m/s, and a cheetah up to 29 m/s, maintaining such a pace for several minutes. However, in long-distance running, trained human athletes achieve results that most animals would envy.

We are remarkably well-adapted to long-distance running both anatomically and physiologically. Specifically, compared to other mammals, humans have a higher percentage of so-called "slow" muscle fibers in the legs and pelvic girdle. These fibers contract relatively weakly and slowly but do not tire quickly. Additionally, humans have a record number of sweat glands that can produce large amounts of watery sweat when needed. This helps protect us from overheating during prolonged physical exertion, a process further aided by the absence of fur, which allows sweat evaporation to cool the skin more effectively.

is not an ideal solution from an engineering perspective because the functions of cooling and breathing become linked, and the breathing rhythm in quadruped runners is usually determined by their running gait. This imposes significant limitations on speed selection: quadrupeds generally have an optimal running pace at which their energy expenditure per kilometer is minimized. Any deviation from this optimal pace makes running much more costly. Humans are better designed in this regard: sweating is independent of breathing, and the breathing rhythm while running on two legs is not as tightly constrained by gait (we don’t have to take exactly one breath per step).

Based on these facts, anthropologists have long hypothesized that adaptation to long-distance running under the scorching sun played an essential role in human evolution. It is possible that our ancestors had to master this kind of running to effectively compete with strong and well-armed scavengers and predators in the Pleistocene African savanna.

ENDURANCE HUNTING

It is suggested that our ancestors, possibly as far back as Homo erectus, practiced what is known as "endurance hunting" (also called persistence hunting or exhaustion hunting). In this type of hunt, a slow-running hunter relentlessly pursues fast prey for hours or even days, driving it to total exhaustion. This surprising (from a city dweller’s perspective) method of obtaining food is still used by some hunter-gatherer groups today. The most well-known are the San (Bushmen) of the Kalahari Desert.

Namibia, Kalahari Desert, Kalagadi Transfrontier Park Bushmen/Photo by In Pictures Ltd./Corbis via Getty Images

Two main objections have been raised against the idea that ancient humans were adapted for endurance hunting. First, such hunting should be energetically extremely inefficient: the enormous energy expenditure of the hunter would not be compensated by the meat obtained, especially considering that not every hunt is successful, and the prey killed far from home still needs to be dragged back to the camp where hungry tribe members are waiting. Second, opponents argued that endurance hunting is practiced by only a few communities of modern hunter-gatherers. It's a rarity and an exotic practice, so why should we think it was common in the past?

In 2024, anthropologists Eugene Morin and Bruce Winterhalder provided comprehensive responses to these objections. Their study consisted of two parts. First, they refined the estimates of the energy balance of different hunting methods, using modern data on energy expenditure during walking and running at various speeds. They found that endurance hunting could be a quite justifiable endeavor, especially when the prey is large. Moreover, running or alternating walking with jogging is more efficient than trying to exhaust prey by walking (which is also possible) because the increase in energy expenditure from switching from walking to running is more than offset by the reduction in pursuit time.

A Bushmen standing in tall grasses of the Kalahari uses a bow and arrow on a hunt, southern Namibia, Africa /Alamy

The second part of the study was ethnographic. The researchers conducted a thorough search of the internet and specialized ethnographic databases for any mentions of prolonged pursuit by hunters. The success of their endeavor was aided by the fact that, in recent years, there has been an active process of digitizing and uploading old paper documents containing valuable ethnographic information.

As a result, they were able to compile an impressive collection of reports on endurance hunting: a total of 391 descriptions. This is an order of magnitude greater than the number of descriptions previously available to anthropologists studying the topic. The collected data spans the period from the 16th century (mentions of endurance hunting among Native Americans were even found in the writings of Spanish conquistadors) to the present day. A typical example is the Kutchin hunters from the northwestern part of North America (1850s): "An old Indian told me:

"An old Indian told me: In the old days, we hunted with bows and spears. Our young men were strong back then." "We hunted moose by chasing it down on snowshoes, and we could run all day like wolves. Nowadays, the young men have become lazy and weak. They prefer to hunt moose in the fall when it's easy to kill. They ride on sleds pulled by dogs and are afraid to run all day."

In most cases, endurance hunting follows the same pattern:

1) The hunter encounters prey that is too far away to use their weapon effectively.

2) The pursuit begins, and the hunter initially falls far behind.

3) The prey stops, trying to find shelter or rest.

4) The hunter keeps running and soon catches up with the prey, which then flees again.

5) This cycle repeats many times, with each iteration reducing the distance the prey allows the hunter to approach.

6) Finally, the hunter catches up and kills the exhausted prey, often without resistance.

Деректер анализі көрсеткендей, 20-шы ғасырдың бірінші жартысына дейін бұл аңшылық тәсілі құрлық атаулының баршасындағы аңшылар арасында кеңінен қолданылған. Соңғы 70–80 жылда бұл әдіс жайындағы естеліктер күрт азайып, бүгінде ол толықтай дерлік жоғалып бара жатқан тәжірибеге айналды. Қазіргі аңшылардың төзімділікке сүйене аңшылықтан бас тартуының ықтимал себептеріне мылтықтың қолжетімді болуы, олжа санының азаюы, жылқы мен басқа да көлік құралдарының пайда болуы жатқызамыз.

Төзімділік арқылы аңшылық— бұғы, бизон, аю, антилопа, жылқы, зебра мен тіпті керіктерге жасалған. Төзімділікке сүйенген аңшылық тек ыстық елдерде ғана емес, салқын климатты аймақтарда да, тек ашық жерлерде ғана емес, ормандарда да кеңінен қолданылған. Энергия шығынының шамадан тыс көптігі туралы айтар болсақ, аңшылар бұл шығынды барынша азайту үшін көптеген айла-тәсілдерді қолданғаны анықталды. Мысалы, олжаның ұзақ уақыт жүгіруіне қиын болатын күндері аңшылыққа шығатын. Солтүстіктегі аңшылар бұлан немесе бұғының тезірек шаршауы үшін терең қарды немесе тапталған қар бар уақытты таңдайтын, есесіне аңшының өзі шаңғы немесе қарлы аяқ киім сияқты техникалық құралдарды қолданады. Африкалық аңшылар жирафты қуаламас бұрын жердің жаңбырдан кейін лай болғанын күтетін, ал құрғақ ауа райында жирафты қуалауға тырыспайтын. Көп жағдайда аңшылар қуып жету оңай болатын жануарды — әлсіз, ауру, паразиттерден титықтаған, қартайған, өте жас, әлсіреген, семіз немесе буаз жануарларды таңдайтын.

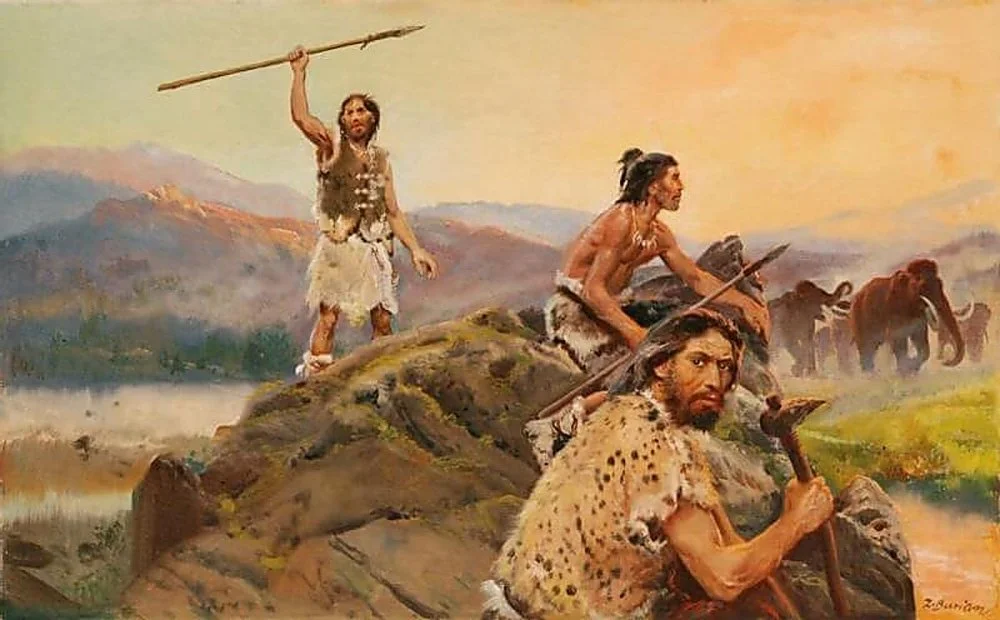

E Boyd Smith. The Hunt in Smith's book The Early Life of Mr Man Before Noah/Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images

Many hoofed animals tend to run in arcs, a behavior that hunters are keenly aware of. Hunters utilize this knowledge to shorten their own route by cutting across the arcs made by the prey and ultimately killing the prey closer to the starting point of the chase. This drastically simplifies the subsequent transport of the prey back to the group's dwelling. Often, a hunter can drive an animal, exhausted from fatigue, right to their home.

For example, an 1860 report about hunters from the Ojibwe people (in the Lake Superior region, USA) describes: "Before the natives acquired horses, running speed must have been highly valued. Since they had to hunt all their game on foot, what is called 'running down game' was a common practice, and even now, they sometimes do it. For example, they often hunt moose this way, especially in winter, when the animal struggles to move through the snow and sinks down, while the Indian easily runs on his snowshoes. A local hunter told me a story about a moose hunt. He had been chasing the moose for half a day and, several times, nearly caught it. But, according to him, he didn’t want to kill it far from home to avoid having to drag it back. So, several times, he sat at a distance from the exhausted animal, allowing it to regain some strength while he also caught his breath. After a few minutes, he resumed his unusual chase, gradually driving the animal closer and closer to his cabin. By nightfall, the animal was close enough to his camp, so he approached, drew his knife, and killed it."

Mammoth Hunt. Zdenek Burian. /Wikimedia Commons

Thus, endurance hunting remained a widespread practice among hunter-gatherers worldwide until recently. The persistent belief in its extreme energy cost and inefficiency seems to be greatly exaggerated. To those softened by civilization, including even seasoned field ethnographers, such hunting indeed seems incredibly labor-intensive and unjustified. However, hunter-gatherers evidently thought differently. To survive, they had to maintain excellent physical condition. Cultural customs, including ritualized athletic competitions that demanded great endurance, helped with this. Endurance runners—both men and women—were highly esteemed in many societies.

The results obtained align well with the hypothesis that endurance hunting played a significant role in human evolution. Most likely originating in Africa, this practice then spread across the world. As humans adapted to their cultural environment, they were subjected to selection for endurance running abilities over thousands of years.