When discussing the victims of Stalin's repressions, most historians tend to focus on the dekulakizationi

- 1. What Was the Special Settlement System and How Did It Work?

- 2. The Confusion Between the 1948 and 1951 Decrees

- 3. The Postwar Period, Famine, and Its Causes

- 4. How It All Began: Khrushchev's Initiative

- 5. Who Could Become an Ukaznik

- 6. How the Decree Worked: The Case of Anna Alkovskaya

- 7. How the 1948 Decree Was Enforced in Different Regions of the USSR

- 8. Where Anna Alkovskaya Was Sent

- 9. Anna Alkovskaya’s Journey to Almaty

What Was the Special Settlement System and How Did It Work?

The foundation of the special settlement system can be traced back to the Soviet kulak exile policy of the 1930s. Until 1944, special settlements were under the jurisdiction of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs’s (Naródny Komissariát Vnútrennih Del, abbreviated as NKVD) Department of Corrective Labor Colonies (OITK). On 17 August 1944, the special settlement department was reorganized into an autonomous system responsible for the administrative management, control, and supervision of special settlers.

988,373 individuals—resided in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic (Kazakh SSR)

The foundation of the special settlement system can be traced back to the Soviet kulak exile policy of the 1930s. Until 1944, special settlements were under the jurisdiction of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs’s (Naródny Komissariát Vnútrennih Del, abbreviated as NKVD) Department of Corrective Labor Colonies (OITK). On 17 August 1944, the special settlement department was reorganized into an autonomous system responsible for the administrative management, control, and supervision of special settlers. During the Second World War and in the postwar years, the number of ‘special settlers’ increased significantly. By early 1953, the system of special settlements had reached its peak, covering 2,753,356 people. The largest proportion of them—988,373 individuals—resided in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic (Kazakh SSR), making it the largest administrative and territorial center of the special settlement system. As a comparison, all the Central Asian republics (Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan) collectively accommodated about 380,000 special settlers. Western Siberia ranked second in terms of population, hosting 758,000 people (covering the Krasnoyarsk and Altai Krais as well as Novosibirsk, Tomsk, Omsk, and Tyumen regions).

The Confusion Between the 1948 and 1951 Decrees

In the system of special settlements, there were two official categories of ‘indicated’ special settlers: the contingent ‘of the Decree of 2 June 1948’ and the contingent ‘of the Decree of 23 July 1951’. The decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, titled ‘On Measures to Combat Antisocial, Parasitic Elements’, was adopted on 23 July 1951. Some historians consider it the urban equivalent of the 1948 Decree, but this is a debated issue.

Despite similar wording, these two decrees were quite different. First, the peasant ‘indicated’ settlers faced the strictest regime conditions within the special settlement system during its most intense enforcement period, from 1948 to 1953. Second, the decrees differed in scale: as of 1 January 1953, the number of special settlers covered by the Decree of 2 June 1948 was 27,275 people, while under the Decree of 23 July 1951, it was only 591 people. Third (and most importantly), these decrees differed in purpose. The 1948 Decree did not address social deviations but targeted collective farmers who were not actively involved in the collective economy. The primary purpose of the 1951 Decree was to combat deviant behavior, such as begging and vagrancy.

Due to their similar phrasing—‘On the Relocation of Individuals Who Willfully Avoid Work and Lead an Anti-Social, Parasitic Lifestyle (1948)’ and ‘On Measures to Combat Anti-Social, Parasitic Elements (1951)’ —both groups of deportees came to be associated with the term ‘parasites’ (тунеядцы). However, in the first case, the targets were peasants who often worked as much as they could simply in order to survive.

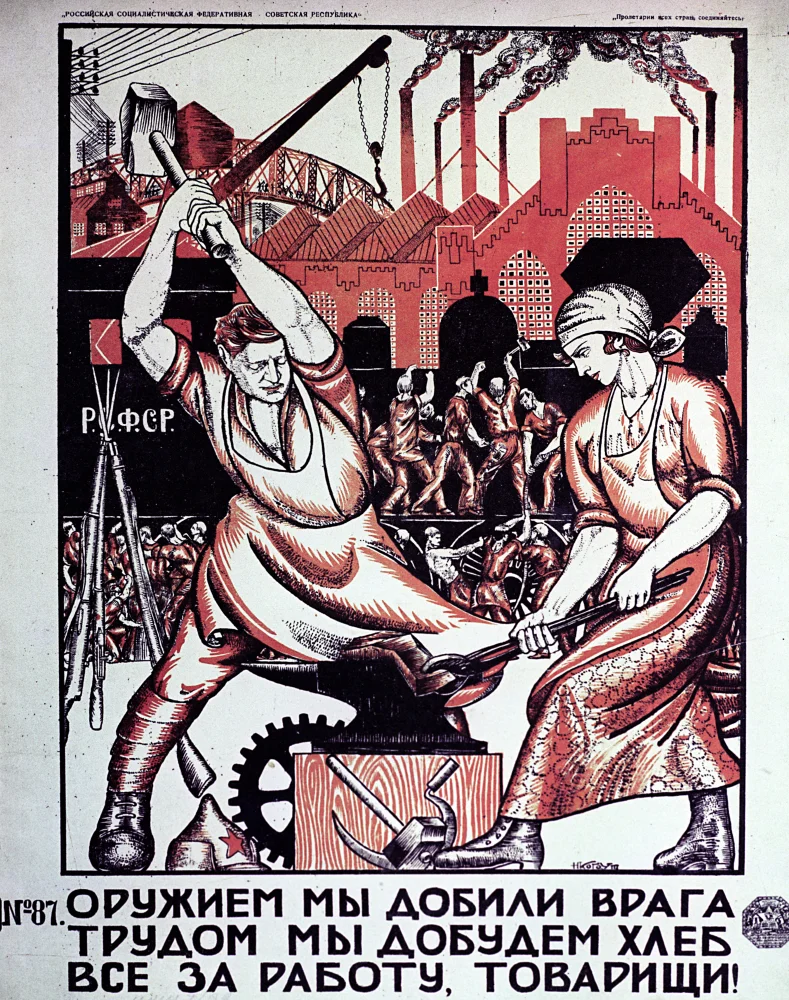

Alexey Sverdlov. Poster "We finished off the enemy with weapons, we will earn bread with labor. All to work, comrades!" Artist Nikolay Kohout (pseudonym Kog) 1920/RIA Novosti

Due to their similar phrasing—‘On the Relocation of Individuals Who Willfully Avoid Work and Lead an Anti-Social, Parasitic Lifestyle (1948)’ and ‘On Measures to Combat Anti-Social, Parasitic Elements (1951)’ —both groups of deportees came to be associated with the term ‘parasites’ (тунеядцы). However, in the first case, the targets were peasants who often worked as much as they could simply in order to survive.

The Postwar Period, Famine, and Its Causes

The Soviet Union emerged from the Second World War in an incredibly dire position. The situation was further exacerbated by a widespread famine that began in 1946 and lasted for several more years. Rough estimates suggest that between 1946 and 1948, around 2 million people across the country died from hunger and other diseases, including enduring a typhus epidemic.

Researchers identify three main, interconnected causes of the famine in the USSR. The first two are postwar hardships and the severe drought of 1946. The third, arguably the most significant, is Soviet economic policy, which dealt the greatest blow to agriculture.

The ruins of a former flour mill in Volgograd (Stalingrad) bear witness to the fierce fighting that went on in the city. Сirca 1950/Photo by Richard Harrington/Three Lions/Getty Images

The drought led to poor harvests, but the policy of compulsory grain requisition to build up reserves and for sale abroad remained firmly in place. This directly affected the payment for labor in the collective farms, known as trudoden (meaning workdays)1

Since 1946, most collective farms reduced the amount of grain allocated as payment for workdays, and in some collective farms, they stopped distributing it altogether. Thus, to survive, peasants had to rely solely on themselves and their private subsidiary farming.

Man Traveling by Oxen Pulling Cart/Getty Images

In that same postwar year, nearly 20 per cent of able-bodied collective farmers across the USSR did not meet the mandatory minimum of workdays. The number of workdays was calculated based on standards established in 1942 at the beginning of the war. According to the decree, collective farm members were required to work between 100 and 150 days per year, depending on the region in which they lived, for the benefit of the collective farm. Those who failed to meet the minimum without valid reasons were tried and sent off as corrective labor on collective farms for up to six months. In such cases, up to 25 per cent of their payment was deducted in favor of the collective farm.

100-150 days had to be worked by collective farmers for the benefit of the collective economy

The decree ‘On Increasing the Mandatory Minimum of Workdays for Collective Farmers’ was passed in 1942, and over the five years of its implementation, nearly a million people were brought to trial. However, evasion of work on collective farms did not cease. After the Second World War, more and more peasants returned to managing their own subsidiary farms to survive. At the same time, they retained formal membership in collective farms in order to have access to a private plot of land, which they could use as collective farmers. Those who used this survival strategy were referred to as ‘near-collective elements’, ‘false collective farmers’, or ‘fictitious collective farmers’. Their behavior was seen as a ‘threat to the socialist system’ and the collective farming model. In response, the state launched a campaign against what was called the ‘parasitic way of life’.

How It All Began: Khrushchev's Initiative

It all started with a memo from Nikita Khrushchev, who was, at that time, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. In the document, which he addressed to the Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, Lavrentiy Beria, in early February 1948, Khrushchev proposed the adoption of a law to strengthen discipline in the collective farms of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Ukrainian SSR). He supported his proposal with specific examples:

On the Peremoha collective farm in the Kyiv region, there is a collective farmer named Iosif Ivanitsky, born in 1900. In 1927, he was convicted of horse theft. After serving his sentence, he returned to his village, where he continued his criminal activities. In 1934, he was convicted again for stealing a cow and sentenced to eight years in prison. At the beginning of the war, he returned to the village, and during the German occupation, he was the foreman at a communal farm. Now, Iosif is a member of the collective farm, enjoying all the privileges of a collective farmer. However, he avoids work and lives off non-labor income—buying cattle and speculating in meat and other goods.

Khrushchev's proposal was soon scaled up to the national level, and less than four months later, on 2 June 1948, the decree ‘On the Deportation to Remote Areas of Persons Who Persistently Avoid Labor and Lead Antisocial, Parasitic Lifestyles’ was adopted. The decree applied to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), the Ukrainian SSR, the Byelorussian SSR (except for the western regions of Ukraine and Belarus), and the Karelo-Finnish, Georgian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Uzbek, Tajik, Turkmen, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz SSRs.

Family and Their Belongings on a Horsecart/Jerry Cooke/Corbis via Getty Images

Who Could Become an Ukaznik

The decision about which fellow villagers deserved exile was made by the general assemblies of collective farmers, villages, or rural communities.

These assemblies were authorized to issue ‘public verdicts on the expulsion from the village of individuals who stubbornly refused to work, led an antisocial lifestyle, undermined labor discipline in agriculture, and whose presence in the village threatened the well-being and security of collective farms and their members’.

Such decisions were made through open voting at general meetings, requiring only a simple majority for approval.

Peasant of a Soviet village vote for the collectivization of their lands, 1930/Alamy

After the public verdict was issued, the individuals were placed in pre-trial detention ‘to prevent possible escapes or acts of revenge’. At this stage, the district executive committees (rayispolkoms) became involved. They had seven days to review the public verdict and either approve or reject it. If the verdict was approved, the punished kolkhoz members, now ‘Ukazniks’, were exiled for eight years to remote areas designated by the USSR Council of Ministers, typically harsh and difficult places to live. Family members could voluntarily accompany the ukazniks to the special settlement. Historians note that this decree gave local authorities the power to exile almost any ‘undesirable’ citizen to distant regions.

How the Decree Worked: The Case of Anna Alkovskaya

Archive sources contain numerous cases involving ukazniks, including the illustrative case of Anna Alkovskaya (name changed for ethical reasons). Anna Alkovskaya's personal file contains a copy of the public verdict issued against her and another ‘false collective farmer’ (his name has also been changed). It reads:

Public Verdict:

The collective farmers' meeting of the Vesely Trud [meaning ‘cheerful labor’] collective farm, Altai Krai, was held on 25 June 1948.

Present: 310 people.

Guided by the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated 2 June 1948, the general meeting of the collective farmers of the Vesely Trud collective farm resolved that:

-

Matvievsky Kirill Sergeyevich, born in 1903, residing on the territory of the Vesely Trud collective farm since 1939, was a false collective farmer. Throughout his residence, he did not work for the collective farm but took advantage of its benefits.

His family, consisting of two able-bodied members, systematically avoided work while concealing their parasitic lifestyle. Matvievsky temporarily and fictitiously took jobs in various organizations and institutions to obtain necessary documents but subsequently worked nowhere.

He owned a house, three heads of cattle, seven sheep, a workhorse, two carts, and up to 70 sotkas (0.7 hectares) of garden land and regularly violated the agricultural cooperative's charter.

-

Alkovskaya Anna Gerasimovna, born in 1928, was a collective farmer of the Vesely Trud collective farm. In 1947, she worked poorly, earning only 140 workdays for the entire year, and in the first six months of 1948, she accumulated only 22 workdays. Through her actions, A. Alkovskaya undermined labor discipline within the collective farm.

Over the past two years, she systematically violated the agricultural cooperative’s charter regarding land use, kept five heads of cattle in her household, and engaged in the theft of collective farm timber.

The general meeting of the collective farm resolves to issue a public verdict:

-

Matvievsky Kirill Sergeyevich, born in 1903, a false collective farmer of Vesely Trud;

-

Alkovskaya Anna Gerasimovna, born in 1928, a collective farmer of Vesely Trud,

To be exiled to remote regions of the country for a term of eight years each.

We request the district executive committee to approve the verdict of the Vesely Trud collective farm meeting.

Translated from bureaucratic to plain language, ‘systematically violated the charter of the agricultural commune in land use’ most likely meant that Alkovskaya cultivated more than the allotted amount of land for personal use and gathered firewood from the forest without permission. Mentioning the number of livestock in the verdict might indicate that she exceeded the permissible livestock limit set by the cooperative's rules.

Questions also arise regarding workdays: at the time of Alkovskaya's deportation, the norms of the ‘On Increasing the Mandatory Minimum of Workdays for Collective Farmers’ decree passed in 1942 were in effect, which set a minimum of 150 days for cotton-growing regions and 100 to 120 days per year for other regions.

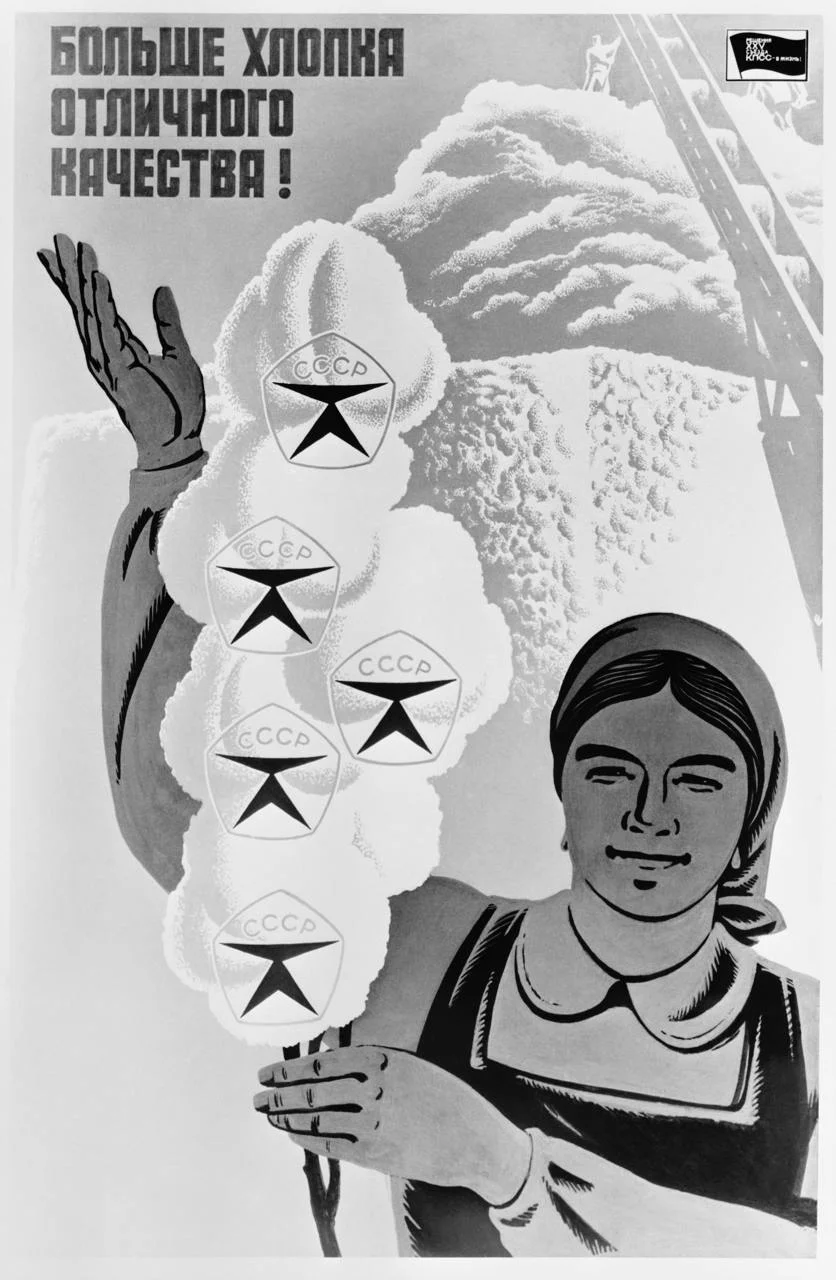

USSR. June 28, 1977. Poster by artist S. Zhmurenkov, Plakat publishing house/TASS photochronicles

A thorough review of the public verdict was deemed unnecessary. The very next day, on 26 June, the district executive committee examined the case and issued its decision:

District Executive Committee Decision:

Classified

Decision No. 172

District Council of Workers’ Deputies Executive Committee

June 26, 1948

ISSUE: Approval of the Public Verdict by the Citizens’ Assembly of the Vesely Trud Collective Farm, ‘On the Exile of Persons Leading a Parasitic Lifestyle to Remote Areas of the Country’, in accordance with the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR Dated 2 June 1948.

After reviewing the minutes of the citizens’ assembly of the Vesely Trud collective farm held on 25 June 1948, and its issued public verdict, the District Council Executive Committee

RESOLUTION:

To approve the public verdict of the general assembly of the Vesely Trud collective farm on the exile of citizens Matvievsky Kirill Sergeyevich and Alkovskaya Anna Gerasimovna to remote areas of the country for a term of eight years each.

Acting Chair of the District Executive Committee: [Name and signature]

Secretary of the District Executive Committee: [Name and signature]

How the 1948 Decree Was Enforced in Different Regions of the USSR

Notably, the public verdict against Anna Alkovskaya almost precisely followed the instructions outlined in regulatory documents issued shortly after the decree was passed. Among these was a ‘memo’ for the party leaders of the regional republics, oblasts, and districts detailing the procedures for applying the decree. Almost every single one of the eighteen points from the memo were reflected in the verdict except one—allowing the accused to explain themselves. Neither Alkovskaya nor her fellow villager was given the chance to speak in their defense.

Fortunately, the decree of 1948 was not enforced with equal zeal everywhere. In some regions, collective farmers were reluctant to punish their fellow villagers for failing to meet work quotas, targeting only the most blatant offenders. For others, opposition came not only from farmers but also from local party leaders.

As a preventive measure, some regions used warnings of possible exile. In such cases, a collective farmer was given a three-month probation period. They signed a pledge promising to correct their behavior and meet the required minimum workdays. If they failed to fulfill these obligations, the general assembly could replace the warning with exile before the probation period ended.

From the time the decree was issued until the end of 1948, tens of thousands of such warnings were issued across all Soviet republics. In the Kazakh SSR, 4,700 collective farmers were granted probation during the first six months of the enforcement of the decree.

In contrast to relative acts of compassion, there were also instances of outright cruelty. Individuals in poor health and mothers with multiple young children were often evicted despite their already dire circumstances.

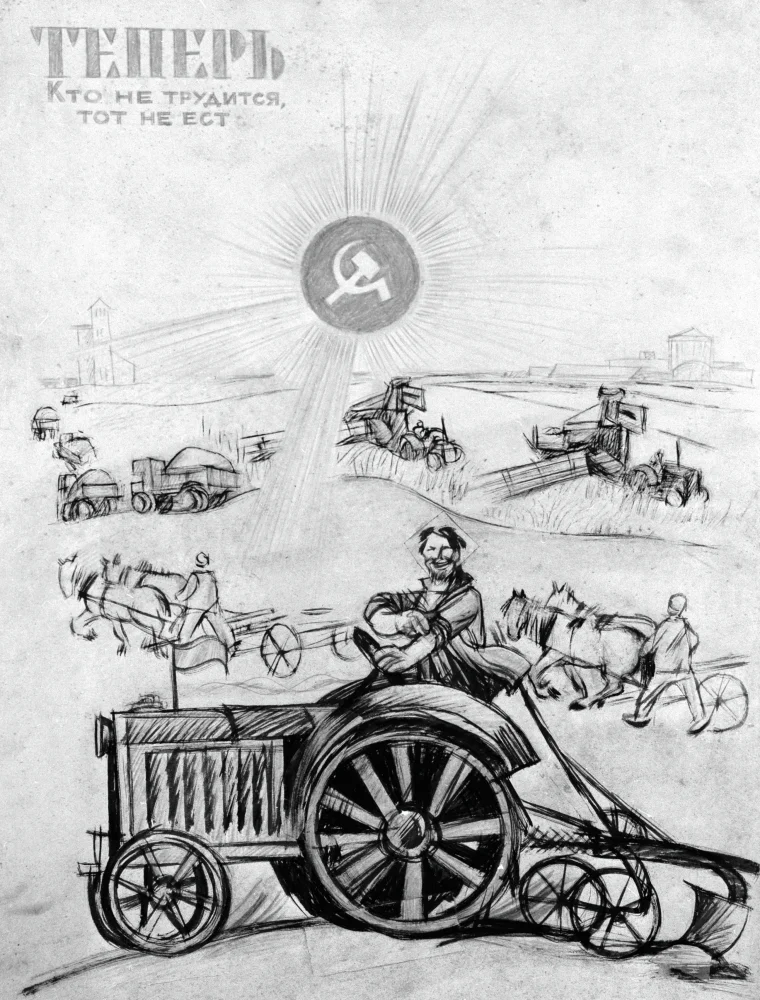

Reproduction of the poster «He who does not work, does not eat» (series «Before and Now») by artist Mikhail Cheremnykh/RIA Novosti

Some local officials exploited the decree to settle personal scores, fabricating accusations against those they disliked. In some farms, however, the decree had the intended effect: labor discipline improved, sabotage of collective farm work decreased, and more applications for collective farm membership were submitted.

During the first three months of the enforcement of the decree, by September 1948, 23,000 peasants were exiled:

-

12,000 from Russia

-

9,000 from Ukraine

-

1,700 from Kazakhstan

Along with the exiles, 9,000 family members voluntarily left, more than half of them children under the age of sixteen.

Where Anna Alkovskaya Was Sent

Following the public verdict, the District Council of Workers’ Deputies Executive Committee issued a guilty verdict on 26 June 1948. On the same day, the local Ministry of Internal Affairs department filled out Anna Alkovskaya’s ‘exile questionnaire’ based on her own statements. The questionnaire contained general biographical data, revealing that Alkovskaya was non-partisan and had six years of education. At the time of sentencing, she was only twenty years old, unmarried, and childless.

Two sections of the questionnaire are particularly noteworthy:

Section 12, titled ‘Criminal Record’, required individuals to indicate whether they had ever been under investigation. Alkhovskaya's questionnaire noted that in 1946, she was convicted for failing to meet her labor-day quota at the Vesely Trud collective farm in the Altai Region. However, her personal file contains no conviction records or other records of any form of punishment. Nevertheless, it is possible that her past reputation as a negligent collective farmer made her one of the first candidates for exile.

Soviet Kazakhstan - Watering the collective farm cotton plantations in Southern Kazakhstan. Latest development in cotton growing is coloured cotton being in several tones. A collective cotton farm: Stalin achieved collectivisation by ruthless force. March 04, 1948/Photo by Pictorial Press/Alamy

Section 15, titled ‘Distinguishing Features’, required the listing of physical traits such as deformities, scars, birthmarks, facial asymmetry, or extra fingers. Anna Alkovskaya’s questionnaire described her as follows:

Blonde with a snub nose, gray eyes, light eyebrows, hair braided into two plaits. Has a round scar above the navel and a small black spot (a single mole) on her breast.

Such detailed descriptions were possible only if the person was fully undressed. This practice was often used by the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) and NKVD officers as an additional method of control and a means of degrading human dignity.

Medical Examination Certificate

One of the documents in her personal file was a certificate from a city health department clinic dated 3 July 1948, confirming that Anna Alkovskaya had passed a medical examination. The results declared her healthy and fit for physical labor.

Turkmenian collective farmers receiving part of their yearly income from the profits of the farm in the farm administration office in the USSR

Exile to the Nadezhda Station

After completing all required checks, Anna Alkovskaya was exiled to the Nadezhda station on the Norilsk railway, confirmed by her Special Settler’s Pledge dated 17 September 1948:

Special Settler’s Pledge

I, special settler Anna Gerasimovna Alkovskaya, hereby pledge to the special commandant's office of the Ministry of Internal Affairs that I will not leave my designated place of settlement in the Dudinsky district. For violating this pledge, I understand I will face criminal prosecution under Article 82 of the RSFSR Criminal Code, punishable by up to eight years of imprisonment.

My place of settlement is Nadezhda Station, and my legal status as a special settler has been explained to me.

Signature

17 September 1948

Pledge Accepted By:

Commandant of Special Commandant’s Office No.___

Norilsk ITL, Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR

In addition to the pledge, Anna Alkovskaya filled out a new form called the Special Settler’s Questionnaire. Notably, her marital status had changed. In the months between her initial exile registration and her transfer, Anna had gotten married, although no supporting documents were included in her personal file.

Anna Alkovskaya’s Journey to Almaty

Clause 5 of the 2 June 1948 decree stated:

A person deported by public sentencing may, after five years of resettlement, petition the district Council of Workers’ Deputies executive committee, that approved the public sentence, for permission to return to their previous residence. The committee may approve such a petition if the person’s conduct and work performance in the settlement are positively reviewed and with the consent of the collective farm members or villagers who initially issued the deportation sentence.

After spending five years at Nadezhda Station, Anna Alkovskaya submitted a petition for early release and return to her previous home.

In an official letter dated 4 January 1954, addressed to the chairman of the district executive committee of the Council of Workers’ Deputies, the Special Commandant of the Norilsk Main Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs stated:

We consider it possible to grant early release to A. Alkovskaya. Her file has no compromising materials, and her work record is positive. However, the district executive committee did not grant her an early release, and Alkovskaya remained at Nadezhda Station.

A year later, she made another attempt to leave the settlement. By then, she had two children, and her younger child's health became the main reason for seeking relocation. In February 1955, Anna Alkovskaya submitted a new request to the head of the Norilsk special command office:

I hereby request permission to leave for the mainland. I have a child aged one year and six months who is ill and needs a change of climate. As the child's mother, I must preserve his health and take him to the mainland. Since I have only one relative, my sister Valentina Gerasimovna Mitrofanova, living in Alma-Ata, 1st Yuzhny village, Chimkent Street No. 45, I will be able to find shelter there. Therefore, I ask to be released solely to my family. Based on the above, I kindly ask you not to deny my request.

Anna Alkovskaya’s request was eventually approved, though it took several months to process. On 26 May 1955, Anna Alkovskaya received permission to depart from Nadezhda Station and left with a travel permit, following a route through Krasnoyarsk and Novosibirsk to Almaty, Kazakhstan.

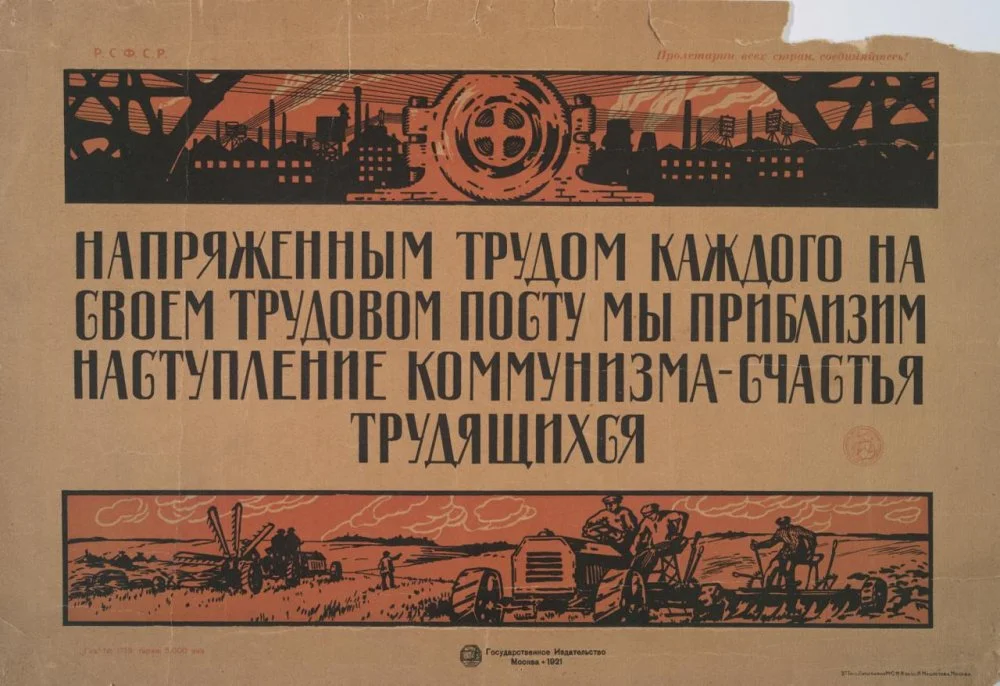

The Efforts of Every One... 1921, Moscow/Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Here, Alkovskaya was again placed under permanent registration. A year later, her term of exile ended, and she was released from the special settlement. This is confirmed by the corresponding receipt, which was added to her file. Thus ended the story of one of the special settlers under the decree, who, by chance, found herself in Almaty. However, many other ukaznik settlers still had a long and challenging path ahead of them to gain freedom and restore their good name.

The history of the ukazniks within the system of special settlements as a distinct category of Stalin-era repressions broadens our understanding of the scale of political persecution in the twentieth century. Moreover, the fate of each ukaznik serves as a reminder of how, under the facade of ‘order and legality’, the Soviet system crushed human dignity and destroyed lives.