Since ancient times, people have constantly sought to find routes, passages of access, that could connect them to other lands. And from small dirt trails grew great pathways, trade routes and military roads, caravan tracks and sea lanes. Along them traveled not only goods and merchants, but also ideas, knowledge, and discoveries. But among all these, the Silk Road held a special place for being the primary web of trails that linked the East and West, shaping the course of world history for centuries to come.

This legendary route was far more than just a network of trade routes. The Silk Road transformed Central Asia into a space of encounters and exchanges: here, empires collided, and caravans arrived carrying not only silk and spices but also beliefs, faith, art, poetry, and music. This region became a true crossroads of civilizations—a place where new meanings and connections were born.

How It All Began

Jules Verne, the author of Around the World in Eighty Days, loved tales of incredible journeys. In one of his nonfiction works, he vividly retold accounts from Marco Polo’s Book of the Marvels of the World in rich detail. While Verne was skeptical of Polo’s stories, he acknowledged that they had sparked interest across most European kingdoms to find new routes to India and China. In essence, this book played a significant role in propelling the world into the Age of Discovery and transforming global trade.

Gigo Gabashvili. Bazaar in Samarkand. Tbilisi, 1896 / Parliament of Georgia library

Marco Polo’s personal story is an incredible one, as he undertook a journey far longer than the heroes of most of Verne’s novels. He left Venice as a teenager and returned twenty-four years later, grown, wealthy, and a seasoned explorer. Over the course of his travels, he covered a distance of nearly 24,000 kilometers, passing through lands that today belong to Kazakhstan. To put that in perspective, this was the equivalent of flying from Seoul to Mexico City and back, an astonishing feat in an age long before airplanes!

Kublai Khan meeting the brothers Polo. 1274 / Wikimedia commons

The Road of Goods and Impressions

The story of the Great Silk Road usually begins with the mission of the Chinese diplomat Zhang Qian in the second century BCE. But trade had existed on those routes even earlier. Chinese silk has been found in tombs in the Middle East, and there simply was no other route to deliver it except through Central Asia.

For over 2,000 years, this region has served as the primary overland artery of Eurasia. And it wasn’t just silk that traveled these routes. Fine horses, exotic animals, songbirds, precious stones, medicines, spices, and manuscripts all moved freely along the Silk Road. But the most valuable things circulating here were, of course, people, and their knowledge and experience.

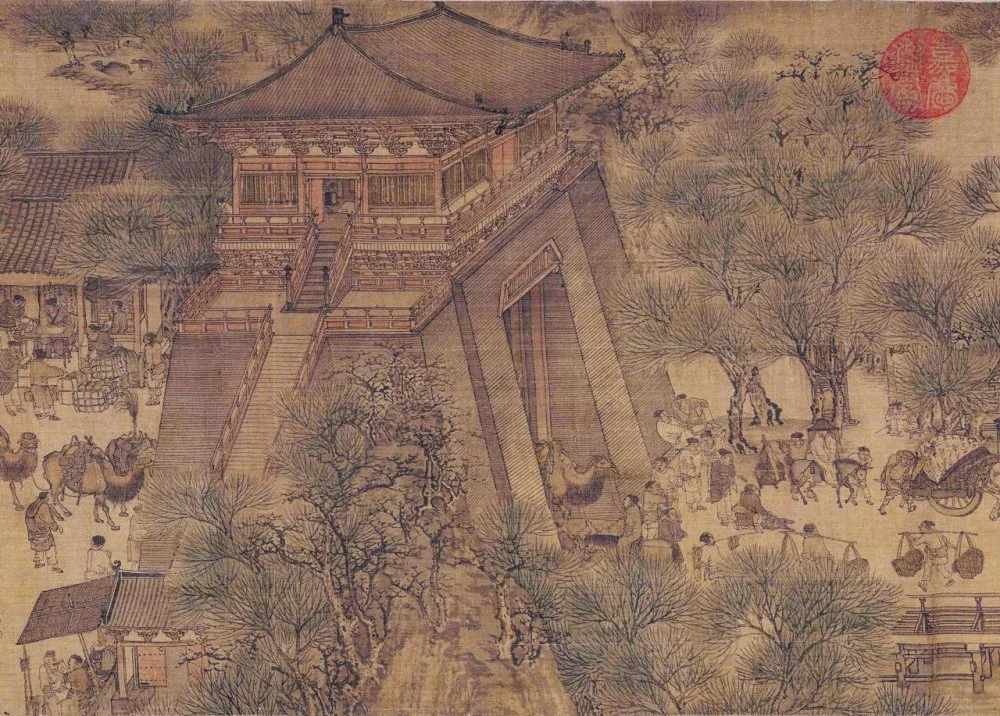

Zhang Zeduan. Bianjing city gate in Along the River During the Qingming Festival. Song Dynasty. 12th century / Wikimedia Commons

During the Tang dynasty, Chinese emperors invited Turkic musicians and dancers to perform at their courts, while the poet Li Bai wrote verses to the rhythms of their music. In return, scholars and monks traveled west in search of new knowledge. Among them was Xuanzang, the monk, philosopher and traveler who crossed the Gobi Desert and the Tian Shan Mountains, later recording detailed descriptions of Central Asia’s roads and cities in his Records of the Western Regions.

Ideas also traveled in the opposite direction. Soon, Buddhism and Islam, Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism, Christianity, and other beliefs reached China. That is why, along the Silk Road, including in present-day Kazakhstan, you can still find numerous ancient sacred sites belonging to different religions. Traders and envoys left inscriptions on rocks in dozens of languages, creating a true encyclopedia of the world of that time.

The Heart of the Earth

Interestingly, the well-known and familiar name ‘Silk Road’ only appeared in the nineteenth century, and it was coined by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877. He dreamed of building a railway across Central Asia that would connect Europe and China, and he compared it to the roads of the past.

Several decades later, the British geographer Halford Mackinder introduced the concept of the ‘Heartland’. According to his theory, it was Central Eurasia, equally distant from the great powers and deprived of maritime access, that held the key to dominating the entire ‘World Island’.

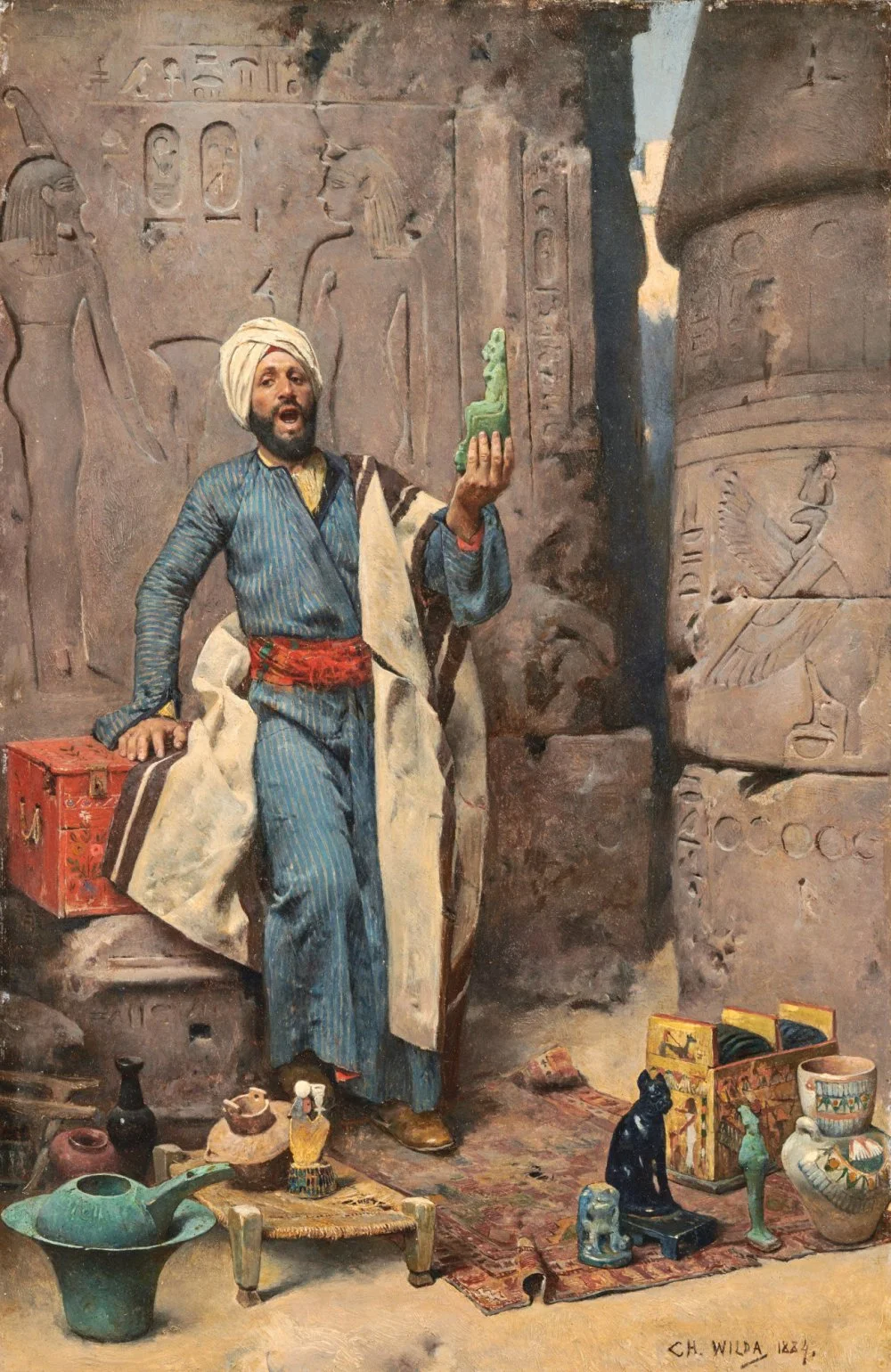

Charles Wilda. The Jade-green Isis or The Egyptian Antiques Seller. 1884 / Sotheby's / Wikimedia Commons

But the strategic importance of the Eurasian region was evident long before nineteenth and twentieth century geographers came along. All great empires sought to conquer it—either for trade or to control its routes. Alexander the Great himself, during his famous eastern campaign, ventured into Central Asia, fought the Saka, and even founded a city in the Fergana Valley before his life was abruptly cut short in Babylon. Another great ruler, the Persian king Cyrus the Great, also attempted to conquer the region, but according to Herodotus, he was defeated and killed by the Massagetae queen Tomyris.

Heavenly Horses and Divine Silk

The nomadic empires, Xiongnu, Turks, and others, were not merely neighbors of the caravan routes—they were key players in its growth and importance. They sold Chinese silk to the West while simultaneously ensuring the safety of the routes across their lands. Over time, the Xiongnu established complete control over the trade routes from Xinjiang to Sogdiana, Bactria, and the Caspian Sea.

Transporting ceramics. Painted silk. Istanbul, Turkey. 15th century / Topkapi Palace Museum / Art Images via Getty Images

At that time, silk was not only a luxury but also a form of currency. It was used to pay soldiers and officials, but much more often, it was exchanged for horses from Central Asia, which were, by far, the most prized commodity for China. Chinese chronicles from the time often linked the very idea of creating the Silk Road—and Zhang Qian’s diplomatic mission to this region—to Emperor Wu of Han’s obsessive desire to acquire ‘heavenly horses’ from Central Asia, described in ancient Chinese records as ‘sweating blood’.

In addition, around 2,000 years ago, the Xiongnu alone received 27 tons of silk annually from the Han Empire as tribute to maintain peaceful relations. Through the trade in horses and tribute, the Xiongnu rulers and Turkic khagans controlled massive flows of silk, mostly sold through Sogdian merchants. All this movement of silk fueled the regional markets of Central Asia, turning it into the heart of the Silk Road.

Jean-Léon Gérôme. The Carpet Merchant. Circa 1887 / Minneapolis Institute of Art / The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

Only a small portion of this silk reached Rome. The majority remained in Central Asian markets. In fact, the Silk Road was not a single route but a whole network of regional paths. Most merchants traveled between their villages and the nearest towns, and Central Asia, with its oases and nomadic culture, was the busiest hub in this network.

Going through the routes was a grueling experience, as caravans had to cross the passes of the Tian Shan and the Gobi, Kyzylkum, and Taklamakan deserts. They covered roughly half the distance from the Mediterranean to the Tarim Basin in about five months. For this reason, the nomadic peoples played a crucial role as intermediaries, supplying travelers with essential items such as animals, water, and food, and ensuring safety across their territories. Their ‘logistical services’ could stretch across hundreds or even thousands of kilometers.

Mongol Globalization

The turning point came in the thirteenth century, when Chinggis Khan united the Mongol and Turkic tribes, creating the largest continental empire in history. It encompassed all the key routes of Eurasia, including the Silk Road. And after the destructive conquests, an era of reform began. The Mongols reorganized the postal system, introduced metal ‘passports’ called paiza or gerege, standardized currency and measures, and strengthened international connections. Across a territory stretching roughly from modern Seoul to Antalya, and from Tbilisi to Guangzhou, the same laws applied. Thousands of relay stations ensured fast and safe travel for merchants and envoys.

Paiza of Abdulla Khan of the Golden Horde. Second half of the 14th century / Museum of the History of Tatar Statehood, Kazan / Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Getty Images

Even after the fall of Chinggis Khan’s empire, this network continued to operate. Central Asia remained the only major transport artery in this landlocked region—until the arrival of airplanes.

The Aerial Silk Road

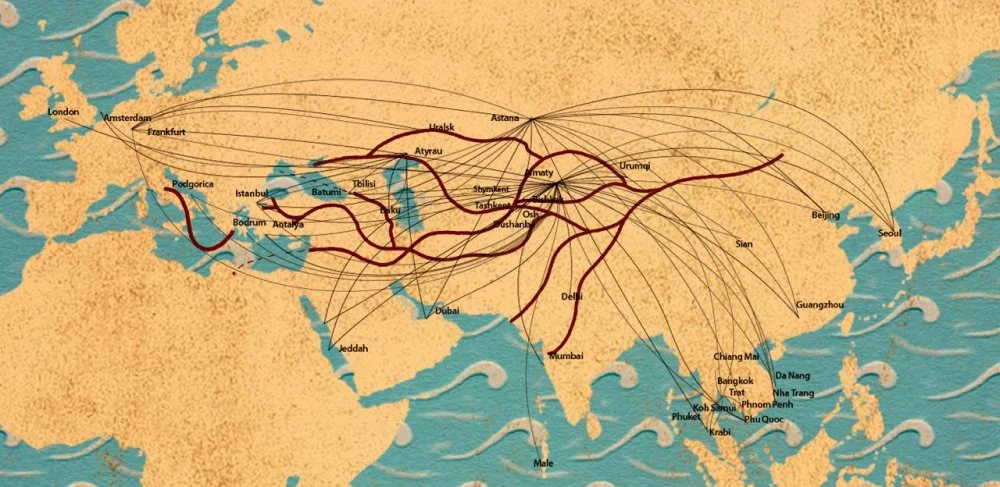

Today, Central Asia is once again fulfilling the same role of being a bridge between distant nations—this time in its international airspace. Air Astana, the region’s largest airline, carries out the same mission once served by the caravan routes: connecting East and West, opening new pathways, and bringing farflung cities closer.

In the spring and summer of 2025, the airline added new destinations and expanded its most popular routes. Today, journeys that once took caravans months can be made in just a few hours from Almaty or Astana to Istanbul, Tbilisi, or Antalya. Direct flights from Kazakhstan now also connect to Frankfurt, one of Europe’s largest transport hubs, as well as to Guangzhou and Mumbai, cities that have long been, and continue to be, vital centers of trade.

For those seeking a continuation of Marco Polo’s ‘journey of marvels’, Air Astana has launched flights to Nha Trang and Danang in Vietnam, cities with pristine white beaches, ancient pagodas, and cuisine shaped by dozens of cultures. Today, Air Astana’s route map resembles a modern Silk Road—and now it stretches across the skies.

Jules Verne and His Prophecy

Let us, however, return for a moment to Jules Verne, where our story began.

In 1893, Verne published the novel Claudius Bombarnac, also known as The Adventures of a Special Correspondent in Central Asia, which imagined the discovery of a railway line between the Caspian Sea and Beijing, a line that did not exist at the time. Since 2014, this route has been accessible via the Trans-Caspian transport corridor.

Perhaps even more prophetic is his observation in the science-fiction novel Robur the Conqueror, written in 1886, seventeen years before the Wright brothers’ first flight:

The future does not belong to balloons. It belongs to flying machines.