‘Princess Leonardo’

A Mysterious Girl Arrives in Kazakhstan

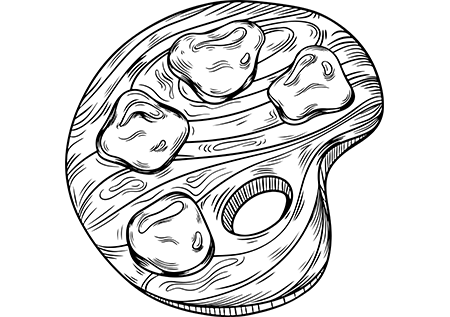

Profile of a Young Fiancee -La bella Principessa. Da Vinci/Wikimedia commons

On 6 June this year, the National Museum of the Republic of Kazakhstan in Astana unveiled a drawing known by various names to the public, including La Bella Principessa,i

This parchment features a drawing rendered in colored pigments, portraying a very young girl attired in the fashion of an Italian aristocrat from the late fifteenth century. The young lady appeared to the public for the first time in 1998. She was entrusted to Christie's auction house by the widow of Giannino Marchig, a Swiss restorer who had lived in Florence for many years.

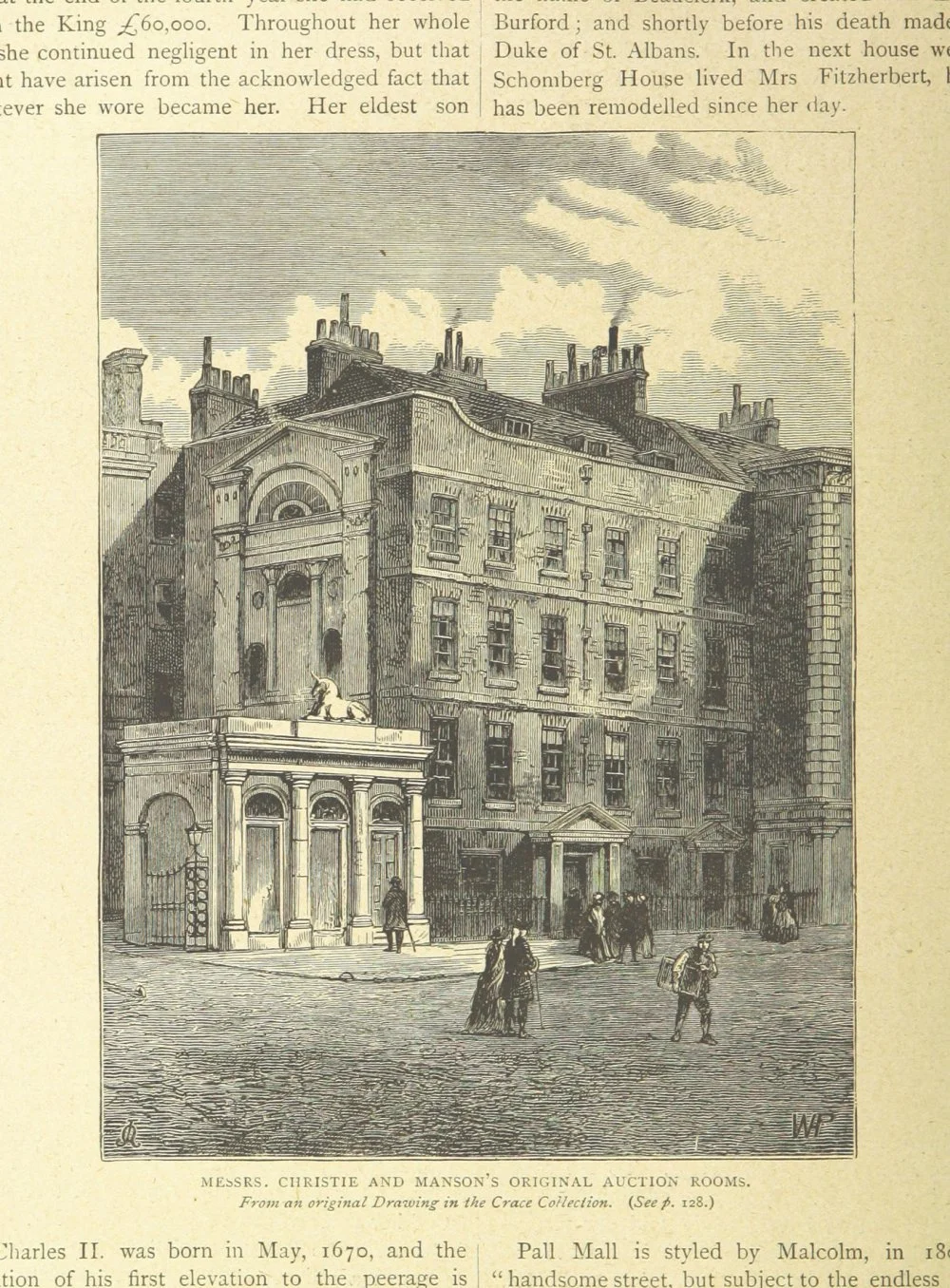

Auction house specialists suggested that it was a nineteenth-century work by a German artist who was skilled at imitating fifteenth-century painting techniques. The work was first sold for USD $22,000 to a New York gallery. Currently, however, the restorer's heirs have filed a lawsuit against Christie’s for what they believe was a malicious error in dating and valuing the work.

Old & New London. By W. Thornbury and Edward Walford. Illustrated The History of Christie's Auction House/Alamy

A few years later, the art dealer Peter Silverman acquired the drawing from the gallery for $19,000 and immediately sent the parchment for radiocarbon dating. The analysis showed that the parchment was produced between the mid-fifteenth and mid-seventeenth centuries. In theory, a nineteenth-century artist could have obtained antique parchment for their work, but such elaborate efforts were not commonly pursued at that time. It is much more plausible to assume that the parchment was used shortly after it was made, which dates the drawing to the fifteenth century, as no one in the sixteenth or early seventeenth centuries used such a style of painting. Further research has revealed that this masterfully executed portrait has several more intriguing features.

The hatching on the drawing was done with the left hand. There is a smudged fingerprint on it, a preserved part of which matches a fingerprint on a painting in the Vatican called Saint Jerome.

The girl is not simply dressed in the clothes of fifteenth-century Italy. Instead, she is dressed specifically in the Milanese fashion of the 1490s. We all know of a left-handed fifteenth-century painter who lived in Milan for a long time—his name is Leonardo da Vinci, who, interestingly, was also the artist of the unfinished masterpiece Saint Jerome.

Leonardo da Vinci. Saint Jerome in the Wilderness/Wikimedia commons

Many experts continue to outright reject the idea that La Bella Principessa can be attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. Their objections stem primarily from the conviction that ‘it cannot be, and therefore it is not’. They argue that a da Vinci work could not have emerged unexpectedly, unrecognized for five centuries. Moreover, since it had been in Marchig's possession for the last few decades, this scenario seems even more implausible—he was a seasoned appraiser, and his home was frequented by Florence's top antiquarians, restorers, and scholars. They surely would have identified a da Vinci painting without question.

Moreover, fifteenth-century Italians did not use pigments in their art as has been done in this painting. Additionally, Leonardo himself never worked with parchment. Overall, the drawing is too ‘rigid’: it is precise but not very expressive, executed too monotonously. So, it is unlikely to have been painted by Leonardo. At best, it could have been by one of his pupils, which would explain the fingerprint, as the master might have corrected something. As for the fact that none of Leonrdo’s left-handed pupils are known or famous, that is a mystery lost to time.

Although several prominent specialists have confirmed the high likelihood that da Vinci is the painter, the art world at large remains staunchly defensive. This, it must be noted, is largely due to the personality of the work's ‘discoverer’, Peter Silverman, who is generally disliked in these circles for his bluntness, indiscretions, and frequent rash comments. Martin Kemp, the author of La Bella Principessa: The Story of the New Masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci, writes, ‘The main problem with this drawing is that it belongs to Silverman.’

In 2015, Shaun Greenhalgh, a British artist who is also a forger and con artist known for creating fakes of ancient works and selling them as genuine masterpieces, added fuel to the fire. After serving a four-year prison sentence, Greenhalgh reformed himself, and the scandal around his name made him famous enough to sell works under his own name. That year, he published his memoirs, A Forger's Tale: Confessions of the Bolton Forger, in which, among other things, he claimed that La Bella Principessa was his creation and that he used a cashier named Sally, who worked at a nearby supermarket, as the model. However, Greenhalgh incorrectly describes the technique used to create the drawing and gets confused about the materials he allegedly used. Scientist and fine art photographer Pascal Cotte writes: ‘He took data from our book but missed some information published in the Italian edition. For example, he does not mention the yellow pigment mixed with gum arabic in the base layer or the lead white highlights.’ Considering that Greenhalgh's entire book is another scandal aimed at reminding the public of his existence, few people believe him. Moreover, the drawing had been documented to belong to Marchig, the Swiss restorer, since at least 1982, which means Greenhalgh would have to have created it when he was only seventeen years old.

This is a picture of a sculpture of faun formerly displayed by the Art Institute of Chicago and attributed to Paul Gauguin. It was recently revealed that this sculpture was forged by Shaun Greenhalgh/Wikimedia commons

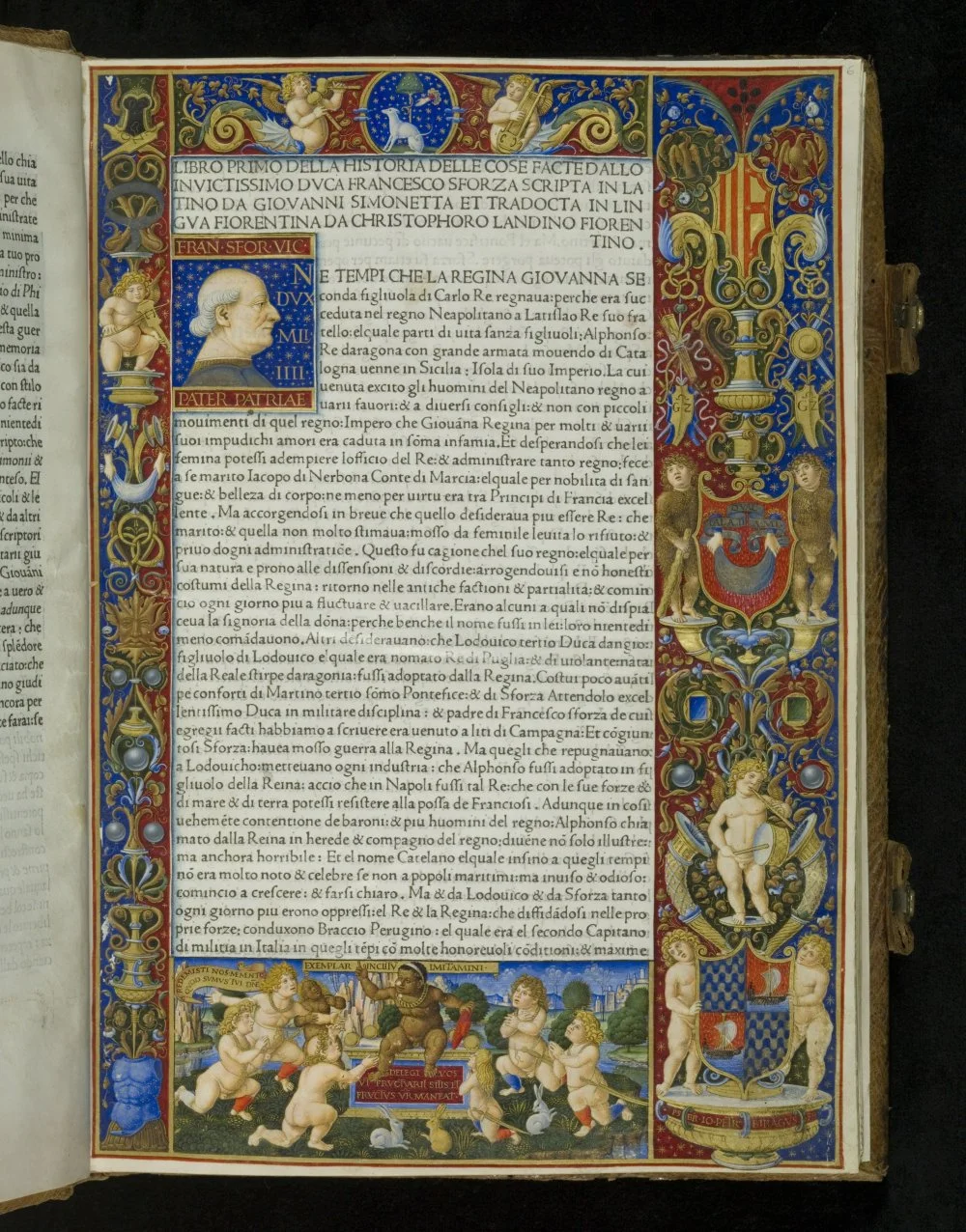

The most recent discoveries into the provenance of the painting have strongly supported the position that La Bella Principessa is a da Vinci work. This was supported by the preservation of four copies of the Sforziada, a poetic tribute to the Sforza family, the rulers of Milan. At the beginning of each copy, there was a portrait of the owner of the book executed on parchment. However, the copy of the Sforziada located in Warsaw is missing this decoration—the page was torn out. It is now recognized that La Bella Principessa could have been part of this incunabulum.i

A leaf from the "La Sforziada" with the portrait of Francesco Sforza in the initial space. 15th century/Wikimedia commons

This would readily explain why Leonardo used parchment, a material he was not fond of, and why the drawing appears slightly more formal and rigid than what is typical for the maestro. If it was a commission from the Sforzas, it would have been hard for the artist to decline such a request, even if he was not particularly interested in creating a ceremonial portrait of a girl wearied by pre-wedding ceremonies.