How Brides Were Kidnapped

Whips, Horses, and Tears

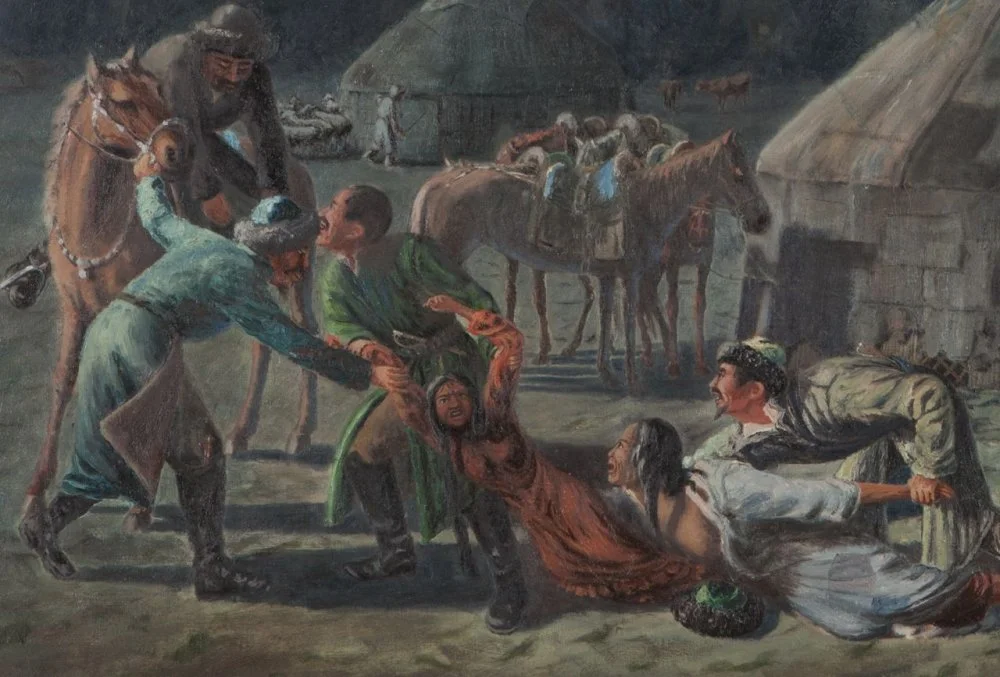

Abilkhan Kasteev. Kidnapping of a Girl for Forced Marriage. 1937. Oil on canvas. 100х135 Signed and dated lower right/A. Kasteyev State Museum of Arts

The Abduction of a Girl (1937) by Abylkhan Kasteev.

The painting is in the Abylkhan Kasteev State Museum of Arts.

One can talk at length about how the practice of exogamous marriages, or marriages outside one's clan, tribe, or even nation, positively affected the health of offspring. Some might even argue that from an anthropological standpoint, bride abductions, in some way, eased the effects of the practice of consanguineous marriages.

However, with the advancement of social structures, roads, and connections between distant settlements, the need to acquire brides in this brutal manner disappeared. For a long time, the abduction of girls was considered an outmoded practice and a criminal act that brought nothing but sorrow.

The romanticized notion that brides were only abducted with the girl's prior consent, or that abduction was one of the options for young lovers to elope from restrictive family members, is shattered when one studies real stories of abductions, including those that happened 100 or 200 years ago.

Men who had no hope of reciprocation, often poor and unable to support a family, which wouldn’t improve the livelihood of the abducted girl anyway, would occasionally kidnap girls. These girls would be forcefully turned into their second or third wives, or, sometimes, into powerless and dependent servants, as the ‘disgraced’ girl was effectively under the abductor's control. Some girls were abducted while extremely young, their childhoods cruelly cut short.

The reality behind the overly romanticized practice of bride abduction is depicted in this painting by Abylkhan Kasteev, the most prominent Kazakh artist. This is not a love story in a picturesque setting but brutal violence. Under the cover of night, the raiders carry out what is known as barimta (bloodless raid). There are no sabers or daggers, so as not to accidentally spill blood, only the kamcha (whips) wielded by the abductors, which is by no means less terrifying. One of the abductors slashes at a woman—either the sister or the aunt of the abducted girl—with such a whip. Meanwhile, in the background, near a neighboring yurt (or the felt tent), we see an armed abductor with a saber at the ready, waiting to see if anyone responds to the cries.

The Rape of the Sabine Women, detail of a fresco in the Queen's Cabinet, Louvre/Wikimedia commons

Men who had no hope of reciprocation, often poor and unable to support a family, which wouldn’t improve the livelihood of the abducted girl anyway, would occasionally kidnap girls. These girls would be forcefully turned into their second or third wives, or, sometimes, into powerless and dependent servants, as the ‘disgraced’ girl was effectively under the abductor's control. Some girls were abducted while extremely young, their childhoods cruelly cut short.

The reality behind the overly romanticized practice of bride abduction is depicted in this painting by Abylkhan Kasteev, the most prominent Kazakh artist. This is not a love story in a picturesque setting but brutal violence. Under the cover of night, the raiders carry out what is known as barimta (bloodless raid). There are no sabers or daggers, so as not to accidentally spill blood, only the kamcha (whips) wielded by the abductors, which is by no means less terrifying. One of the abductors slashes at a woman—either the sister or the aunt of the abducted girl—with such a whip. Meanwhile, in the background, near a neighboring yurt (or the felt tent), we see an armed abductor with a saber at the ready, waiting to see if anyone responds to the cries.

The father, tied up and in his undergarments, lies helplessly on the ground. The mother, her breast exposed in the struggle, vainly tries to fend off the attackers to save her daughter—a small and fragile child. Terrified, the girl screams and cries. Stolen goods are hurriedly carried out of the yurt, and it seems like, by the ‘noble rules’ of the game, the raiders are taking only the captive's outfits, leaving discarded men's clothing on the ground.

Abilkhan Kasteev. Detail of «Kidnapping of a Girl for Forced Marriage». 1937/A. Kasteyev State Museum of Arts

The ‘groom’ reaches greedily from his horse for his prize—hunched over, his eyes glowing in the darkness, he resembles a wild predator. A small black dog toward the right edge of the painting howls, foreshadowing the impending misfortunes for the girl and her family.

Abilkhan Kasteev. Detail of «Kidnapping of a Girl for Forced Marriage». 1937/A. Kasteyev State Museum of Arts

The shabby, repeatedly patched yurt indicates that the girl is the daughter of a poor man, and it is likely that the father will have neither the means nor the ability to find justice against the abductor or to improve his daughter's life, ensuring her at least a decent position in this unwanted marriage through force or money.

Abilkhan Kasteev. Kidnapping of a Girl for Forced Marriage. 1937. Oil on canvas. 100х135 Signed and dated lower right/A. Kasteyev State Museum of Arts