The Mysteries of the Last Supper

Eels with Oranges and a Pouch of Silver Coins

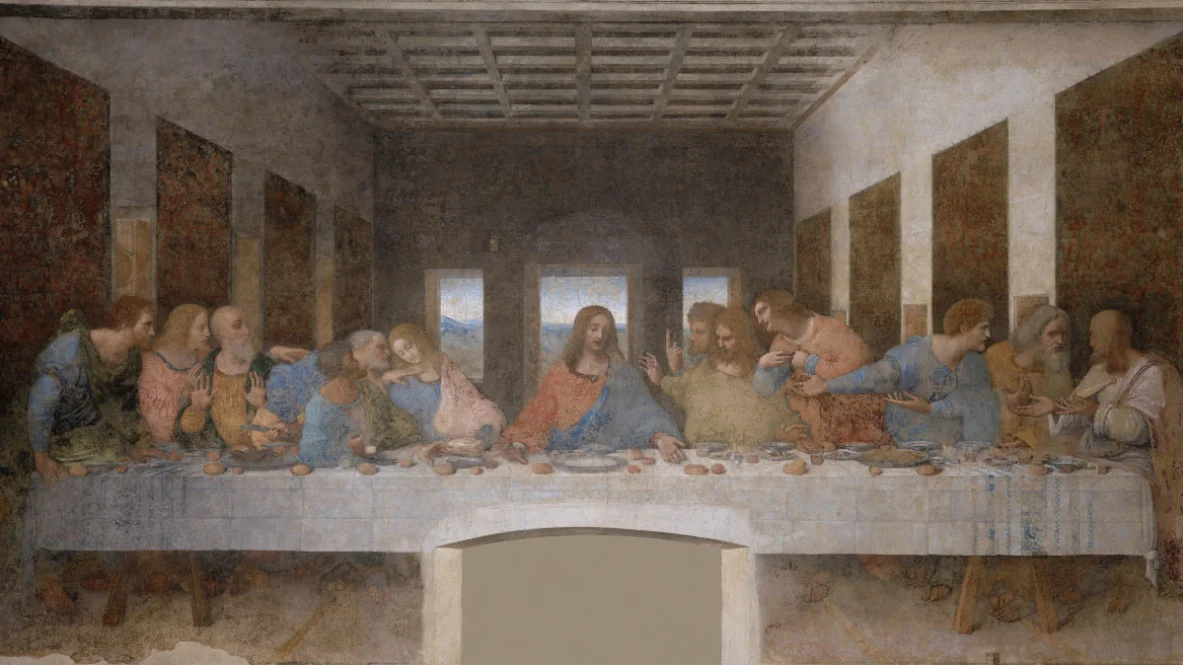

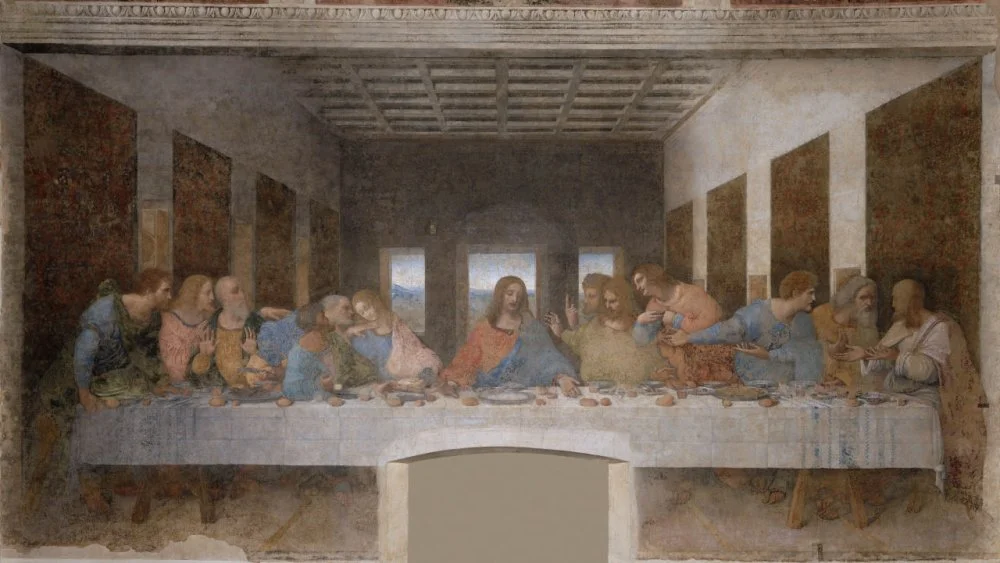

Santa Maria delle Grazie. Leonardo da Vinci. The Last Supper (1495-1498)/Wikimedia commons

There seems to be no dearth of mishaps that this unfortunate masterpiece of the great Italian master has suffered. On one occasion, doors were cut through the frescoes. It has withstood flooding and being covered with mold. The room in which it occupies the wall once housed barracks for Napoleonic soldiers and a stable. During the Second World War, a bomb hit the refectory, blasting part of the structure into brick dust. Let’s not even mention the series of horrifically inept restoration attempts, which likely inflicted the most severe harm of all these incidents. And yet, The Last Supper remains a haunting and powerful testament to human creativity.

For twenty-one years, from 1978 to 1999, a meticulous and scientific restoration of the mural was undertaken, after which The Last Supper was open for public viewing, albeit with many restrictions—no wet or dirty clothes allowed in the refectory, no one could approach the wall, and a visitor could spend a maximum of fifteen minutes inside. Despite all this, it remains one of the most famous paintings in the world.

The mural depicts Jesus during his last supper with his disciples. From a historical perspective, the depiction is rife with anachronisms. The meal described in the Gospels was conducted according to the Greco-Roman standard, and the scriptures have several mentions of the participants ‘reclining’ at the table.

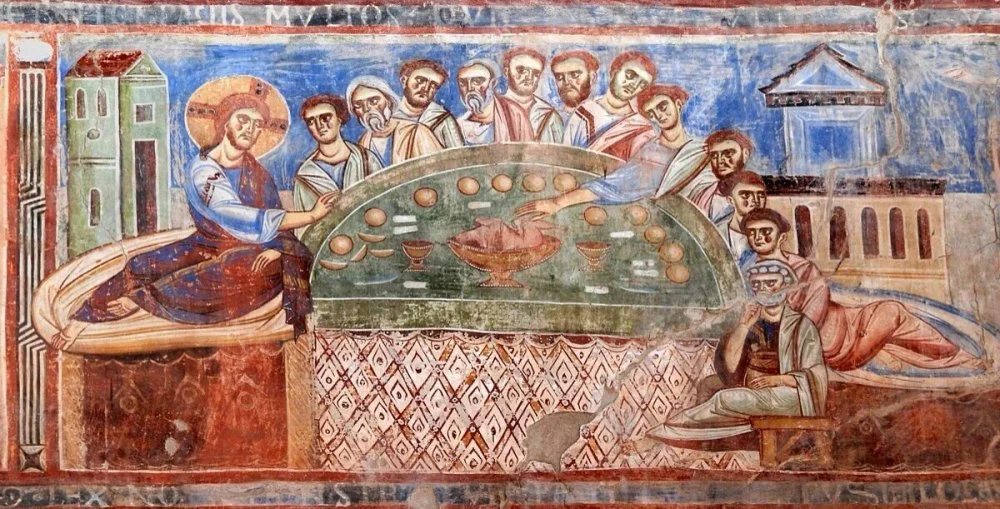

Unknown painters. Last Supper of Sant'Angelo-in-Formis. 11th century/Wikimedia commons

Da Vinci—not the most religious man of his, or indeed any, era—carefully read the Gospels multiple times before executing this commission (as indicated by his notes in his diaries and codices). However, he seems to have ignored the information while painting the mural, which raises intriguing questions. Most often, experts are of the opinion that da Vinci sought to depict the Last Supper in a style close to the monastic meals of his time: the monks sitting modestly at the table on benches would, in a sense, become participants in the supper.

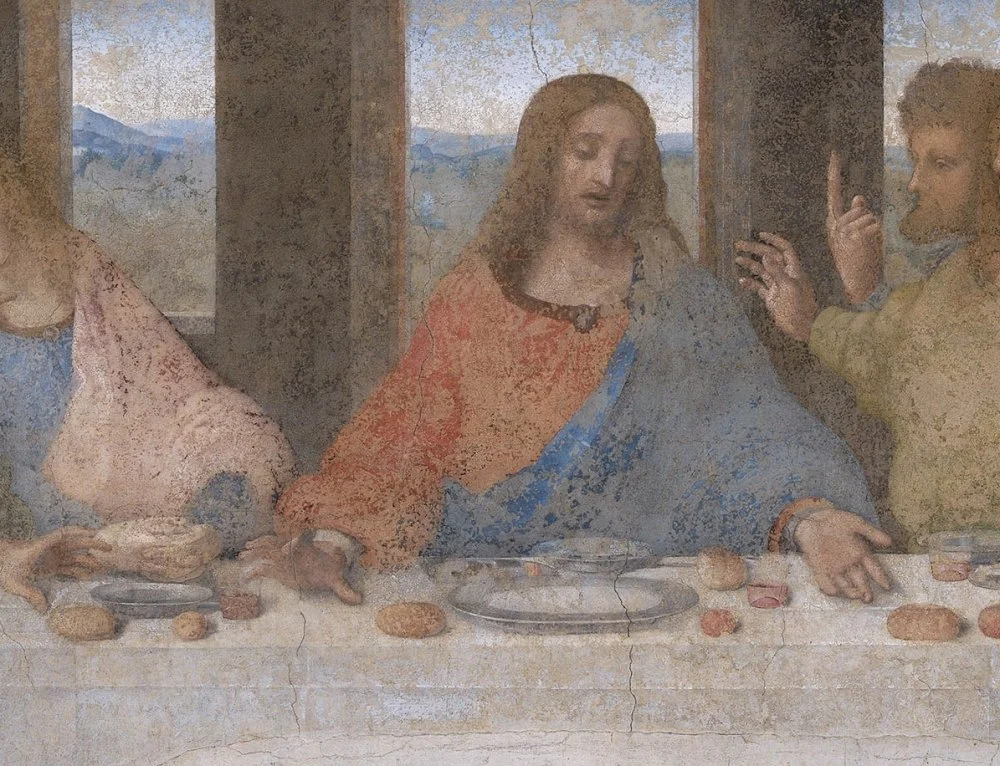

Detail. Santa Maria delle Grazie. Leonardo da Vinci. The Last Supper (1495-1498)/Wikimedia commons

On the table in front of the apostles sits a curious dish—eels layered with orange slices. Its presence is an anachronism because oranges were only cultivated in China at that time, thus they couldn't possibly have been on a table in Judea. This dish was considered an almost indecently expensive delicacy in fifteenth-century Milan, mentioned in moralistic treatises as an example of the corrupt life of the wealthy and wasteful. It is important to note that Italian preachers have had a long-standing dislike for eels. Even in ancient Roman times, Cato the Elderi

Why then did Leonardo include this somewhat scandalous dish in the mural? One theory is that it was a hidden jab at the church hierarchs, who did not deny themselves any delicacies and often indulged in the sin of greed.

The Last Supper has also sparked a number of ‘decryptions’ of the secret symbols in the paintings. Amongst the most famous of these, of course, is The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown's renowned detective novel, where one of the plot keys is the controversial claim that the person seated next to Christ is not the youngest of the apostles, John the Evangelist, but Mary Magdalene.

Obsessive fans have delved deeply into the mathematical intricacies of the masterpiece to find hidden codes and patterns. From calculating the ratios of the architectural elements in the painting against the golden ratio, deriving various formulas, and finding references to numerical records linked to famous musical works, no arcane idea has been left untouched. Unfortunately, however, the boldest and most striking theories have not yet found any scientific confirmation.

Detail. Santa Maria delle Grazie. Leonardo da Vinci. The Last Supper (1495-1498)/Wikimedia commons

However, some details in the painting hold unmistakable meaning. For example, Judas can be identified by the pouch of silver coins he clutches in his fist—the payment for betraying Christ—and by his dark complexion. At that time, darker skin tones were not associated with race, but with having a tan, which in the urban environment was primarily characteristic of vagabonds and riffraff, perpetuating the stereotypes that only vagabonds wandered the streets all day and only respectable people from a higher social class worked indoors.

Next to Judas's elbow is a white spot, and this part of the mural has been irretrievably lost. However, in all copies made when the mural was still intact,i

Giampietrino. Last-Supper. 1520/Wikimedia commons

The apostle Peter holds a knife in his hand, symbolizing the sword with which he cut off the ear of Malchus, the high priest's servant, when Christ was arrested in the Garden of Gethsemane.

Detail, knife. Santa Maria delle Grazie. Leonardo da Vinci. The Last Supper (1495-1498)/Wikimedia commons

The apostle Thomas, who raised his thin fingers to the sky, is the same Doubting Thomas who initially did not believe in the resurrection of Christ and was invited to ‘put his fingers in the wounds’ to be convinced that he was indeed seeing the crucified Jesus.

Detail, Thomas. Santa Maria delle Grazie. Leonardo da Vinci. The Last Supper (1495-1498)/Wikimedia commons

The mural contains another message that may not be immediately clear to modern viewers. Two of the most significant events in Christian lore occurred during the Last Supper. First, Christ announced that one of his disciples would betray him. Second, he pronounced the formula of communion, declaring that his blood and flesh would be embodied in wine and bread, and The Last Supper references both these moments. Christ extends his right hand toward a plate that Judas's hand is also reaching for. This correlates directly with this quote from the Gospel of Matthew:

When evening came, Jesus was reclining at the table with the Twelve. And while they were eating, he said, ‘Truly I tell you, one of you will betray me.’ They were very sad and began to say to him one after the other, ‘Surely you don't mean me, Lord?’ Jesus replied, ‘The one who has dipped his hand into the bowl with me will betray me.’ Matthew, 26:20-23

Detail, hands. Santa Maria delle Grazie. Leonardo da Vinci. The Last Supper (1495-1498)/Wikimedia commons

With his left hand, from the heart, Jesus points to the loaf of bread lying before him and inclines his head toward it, indicating that this bread would henceforth represent the Body of the Teacher to the disciples. Subsequently, the apostles always left a piece of bread on the table during their meals to symbolize Christ. Interestingly, this tradition evolved into the Orthodox custom of placing a slice of bread on top of a glass of vodka, referred to as ‘green wine’,i

The reactions of the characters in the painting allow us to speculate about which of these two messages each of the apostles is responding to. Who among them is already looking for the traitor, and who is trying to comprehend the sacred mystery of flesh turning into bread? Art historians and scholars have shared fascinating theories like these with the public for several decades. There are now numerous combinations of ideas and clever explanations for one interpretation or another, and proponents of different viewpoints often indulge in amusing jabs and retorts toward their opponents in their writings.

Santa Maria delle Grazie. Leonardo da Vinci. The Last Supper (1495-1498)/Wikimedia commons

And such is the nature of The Last Supper—it is more than simply a painting, it is instead an enduring cultural touchstone. Its mere presence can stir up a storm and ignite debate, and in our times, one needs only to recall the scandal caused by the allusions to it during the opening ceremony of the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris.