Jeztyrnaq

Mistress of Beasts and Copper Ore

Akzel Beisembay Jeztyrnak. 2024/Qalam/Beisembay Akzel

One of the most memorable demonic figures in Kazakh folklore is that of the Jeztyrnaq, a woman with brass (copper) claws. Do you remember the story from your childhood? If not, let’s quickly recap it. A lone hunter wandered into a land where no man had ever set foot and met a demonic creature disguised as a beautiful young woman with brass claws.

The Jeztyrnaq had monstrous power, and she could kill birds and small animals with her loud, piercing scream. Similar myths existed among the Kyrgyz, who called the spirit jez tyrmak or jez tumshuk (meaning ‘brass nose’). There are also similar images among the Tuvans (spirit chulbus or shulbus) and the Buryats (mu-shubun).

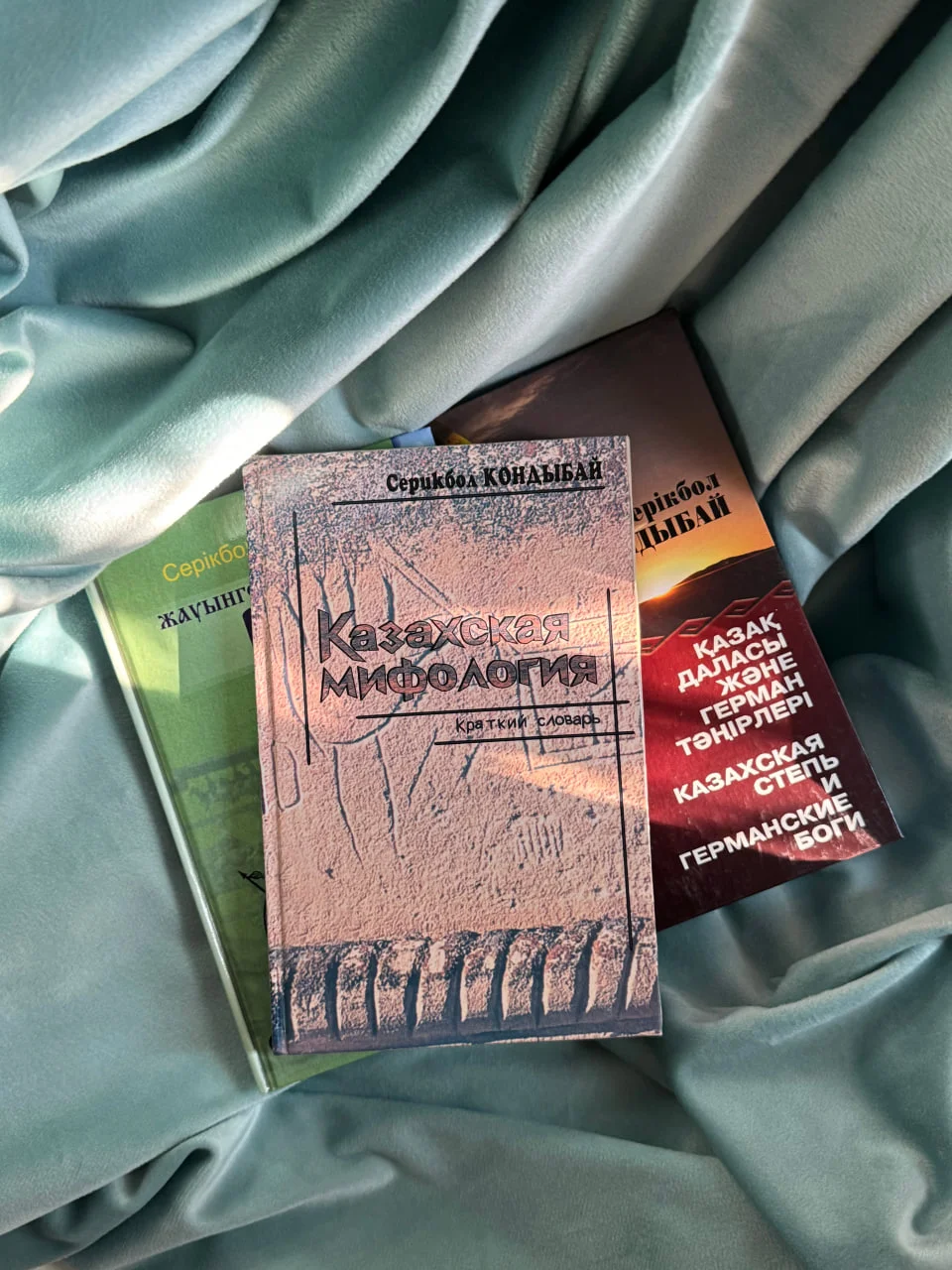

The famous mythology researcher Serikbol Qondybai (1968–2004) studied Kazakh fairy tales that mention this colorful creature. He analyzed these tales in his book Kazakh Mythology: A Concise Dictionary (2005), and later in the sixth section of the second book of his four-volume study Arğyqazaq Mifologiyasy (Mythology of the Pre-Kazakhs, published in 2004, with a Russian translation of published in 2011), titled ‘The Era of the Great Hunter’. All these stories are about a mergeni

Books of Serikbol Kondybai: Brief Dictionary of Kazakh Mythology. Kazakh Steppe and Germanic Gods. Fighting Spirit/Qalam

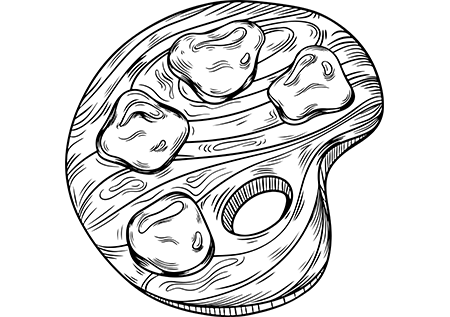

One late evening, a young woman came to the hunter’s campfire, and the hunter invited her to share his meal. He guessed that she was a Jeztyrnaq because her sleeves constantly covered her hands during the meal. When she left, the hunter placed a log by the fire, covered it with his clothes, and climbed up the tree with his rifle. When she returned at night and attacked the log, the hunter killed the demon with a precise shot. He then cut off the Jeztyrnaq’s clawed hand (which is common to all versions of the story). The next day, he met a copper snake, killed it, and cut off its head (and this motif is found only in some versions). On the third day, he met a tautailaq (literally meaning a ‘year-old camel’), a chthonic monster, killed it using the Jeztyrnaq’s hand as a weapon, and then cut off its tongue. On the fourth day, he encountered a Deva Aidahar (a dragon-like creature) and killed it with the tautailaq’s sharp tongue that could cut through anything. Afterwards, he suddenly came across an aul with white yurts, where he met a girl (or girls/peris). She took care of him: fed him, gave him something to drink, and then put him to bed. A few months later, at the crossroads of nine (or in some versions ninety) roads, the girl the hunter met on that memorable night meets him again and gives him a newborn child.

Bahram killing the dragon - Chah-namah. Topkapı Palace collection. Painted in shiraz 1370/Wikimedia Commons

Stories about the man who met a whole aul (village) of peris in the deserted night steppe are still told in different regions as if they really happened to a certain person. Similarly, stories about the Jeztyrnaq are still told. For example, in the Ayagoz district of what is now the Abai region, local Kazakhs during the Soviet era avoided going near the Kusmuryn gold mine at night. According to local stories, one could meet a Jeztyrnaq who could chase a car there, and drivers have even shown traces of her claws on a truck as proof.

Akzel Beisembay Jeztyrnak. 2024/Qalam/Beisembay Akzel

According to Qondybai, this is not just a fairy tale or a hunter’s tale, but a relic, albeit a very profane one, of an ancient mythological narrative whose meaning we can decipher. The hunter in mythology is a cultural hero often found in archaic myths. Another common theme is the astral myth of the celestial hunt, where the hunter pursues a cosmic moose, deer, or argali that transforms into a constellation. And thus, the motif of hunting is associated with the deeds of heroes who slay chthonic monsters. Qondybai draws attention to the names of the main hero hunters in different versions of the stories: Argymergen (where ‘arig’ means ‘otherworldly’, ‘ancient’, ‘from another world’, ‘from the other side’, like the Greek word ‘archē’, meaning ‘origin’), and Esekmergen (literally meaning ‘hunter-donkey’, but Qondybai assumed that the original variant was Eskimergen, which literally means ‘ancient hunter’), et cetera.

Vincent van Gogh. Starry Night Over the Rhone. 1888/Wikimdia Commons

In all versions of the story, the mergen treats the Jeztyrnaq to meat. This action seems to be rooted in an ancient sacrificial tradition where hunters would make a sacrifice to a particular deity or spirit, such as the spirit of an area or the master/mistress of the animals. The hunter has to ‘pay’ the master/mistress for the animals he has caught or killed. This motif is widespread not only among Turkic-Mongolian peoples—for example, the ancient Greek goddess hunter Artemis was the mistress of animals in the pre-classical period in Crete. In the original story, the hunter, in preparing for the Jeztyrnaq’s night attack, covers a trunk, a bundle of brushwood, a ‘branch’, a thick poplar, et cetera, with a chapan robe, that is, we see a tree with human clothes on it. In essence, the hunter creates his own image, a doll, out of a tree (stump, et cetera) and puts his clothes on it. Qondybai believed that

a) the mergen imitates the return to life, the resurrection of the animal he killed;

b) the mergen creates an ongon (doll) to contact the deities/spirits.

This may also be associated with the creation of a tūl, an image, a doll of the deceased dressed in his clothes for the period of one year of mourning. In one version of the story, a hunter later becomes passionately attached to a woman who is actually a tree stump, and this image is probably not coincidental.

Piero del Pollaiolo. Apollo and Daphne/Wikimdia Commons

In some versions, the mergen kills the Jeztyrnaq instantly; in others, he wounds her with an arrow; the wounded Jeztyrnaq runs away, and the mergen pursues her. Following the trail of her blood, he comes to a cave (in other variants, this is described as a hut, a cabin, or the roots of an osier in a dense osier thicket) and finds the dead Jeztyrnaq. According to Qondybai, this is the dwelling place of an ancient deity, or a sanctuary dedicated to that deity.

‘The house (cave) of the Jeztyrnaq is the place of the goddess in the ancient myth (in this case, it does not matter whether she turns out to be the tutelary spirit of the clan, the mistress of the clan territory, the mistress of the animals, or someone else). The mergen who treated the Jeztyrnaq to meat and committed the imitation of a certain murder should now receive a gift from the goddess,’ he writes.

Qondybai compares the image of the Jeztyrnaq to that of the mistress of animals, the hunter Artemis. In the most ancient myths, Artemis took the form of a bear, and human sacrifices were offered to her. In these stories, she was sometimes depicted as a bloodthirsty goddess. Indeed, the echoes of such an ancient mythological image can be seen in the tale of the Jeztyrnaq, who in archaic mythology is a mother goddess, the patroness of hunters and wild animals, and her metal claws are a remnant of the oldest versions of the myth, that is, before she appeared in the form of a clawed beast of prey, such as a bear. The trunk covered with the hunter’s clothes is probably connected with the idea of sacrifice or the imitation of a sacrifice in the hunting rituals of ancient people.

Wall painting of Artemis/Wikimedia Commons

Artemis is a virgin, as are the members of her retinue, but she also received sacrifices from couples before their weddings and patronized women in labor. In contrast to Artemis, the Jeztyrnaq is sometimes described as a wife and mother. For example, there exists a legend about the mergen Sarybas of the Tama clan, which begins similarly to the encounters between hunters and the Jeztyrnaq in fairy tales. The only difference is that Sarybas met not one but three Jeztyrnaqs. After killing two, he wounded the third, who was bleeding, and began to pursue her. The Jeztyrnaq had taken refuge in a cave in the Karatau Mountains, and the mergen followed her in.

The Jeztyrnaq was lying face down at the bottom of the cave, and she turned out to be an old woman. Before she died, she said this:

‘First you met and killed my daughter, then my daughter-in-law. Our men were unfit, cursed by God and punished for breaking their oaths. You saw our women, each worse than the last. You have destroyed us from the root. God’s precious treasure is all in this cave. Don’t try to take all of it—only take as much as you can carry. That’s what Jerūiyq.i

Later, Sarybas told the people that he wanted to share the treasures of the cave, but no matter how much he searched, he could not find the cave again. The legend ends on a philosophical note:

‘This is a nomadic world, it does not stay in one place—today you see it and tomorrow it is gone. What the ears have heard, the eyes will see one day. But where have all the Jerūiyqs gone?’

Mystical mountains of Kelinshektau in the Karatau massif, Kazakhstan/Alamy

The rich treasures in the cave and the Jeztyrnaq’s offer to the hunter to take his share of these treasures are no coincidence, for the old woman Jeztyrnaq is an ancient deity. The hero who fulfills certain conditions can receive a gift from her hands. Although men of the Jeztyrnaq’s family are mentioned in fairy tales, it is mainly she and her daughter who act. Qondybai writes,

‘The presence of only women characters (the old woman, her daughter, and daughter-in-law) in the tale of the Jeztyrnaq indicates that the tale was formed on the basis of the oldest mythological ideas of the matriarchal epoch.’

The writer and tradition expert Talasbek Asemkulov (1955–2014) mentioned (orally) that the Kazakhs called the Jeztyrnaq’s husband ‘kisikiyik’ (meaning ‘the saiga man’). This word not only means a reclusive, unsociable, disturbed person, but also, according to volume eight of the fifteen-volume Qazaq ädebi tılınıññ sözdigi (Dictionary of Literary Kazakh), it has a different meaning in folklore. In this context, it describes a humanoid, woolly creature, suggesting that this is the Kazakh name for a cave dweller or a troglodyte.

Big Foot on display at the Ripley's Museum, Newport, Oregon/Alamy

The family, especially the daughter of the Jeztyrnaq, is mentioned not only in the legend of Sarybas but also in some other fairy tales. The mergen takes the Jeztyrnaq’s hand and belongings (gold and silver buttons or pendants or necklaces or a white axe) to his house. He has a daughter, and when she gets married, she coaxes these things out of her father. The mergen does not want to give them to his daughter because he knows that the daughter of the Jeztyrnaq (or her family—wife, husband, children) will eventually come for these things. But in the end, he gives in to his daughter’s insistent pleas. The hunter’s daughter placed her aq otau (white wedding yurt) on the edge of the aul (or in the forest) and waited for the Jeztyrnaq every night. Finally she killed the Jeztyrnaq (several Jeztyrnaqs, in fact!) who came to retrieve her things.

Qondybai comments on this symbolism, writing:

‘It is no coincidence that the Jeztyrnaq has a daughter and a daughter-in-law, and it is no coincidence that in this fragment, the Jeztyrnaq’s daughter, who wants her mother’s things returned, is set in opposition to the hunter’s daughter, who appropriated them, got married, and now lives in a white house on the edge of the aul (forest). The newlyweds’ white house at outskirts, the hunter’s daughter begging her father for only the Jeztyrnaq’s things as her dowry, her sleepless vigils in the yurt at the edge of the aul (in the forest) waiting for the Jeztyrnaq’s daughter, and even her marriage itself show the significance of the “bride” theme and “the ritual of a Jeztyrnaq woman, as a symbolic figure, giving a girl in marriage to someone” in ancient myth. This will be better understood if we consider (as we can see in the third book of the Mythology of the Pre-Kazakhs) the themes of “the white house in the west” and “the old woman and the girls in the white house”. In general, we are far from an exhaustive understanding of the subtext of this fairy tale.’

The appearance of the Jeztyrnaq’s daughter in connection with the marriage of the hunter’s daughter is reminiscent of the sacrifices made to the Greek goddess Artemis before weddings. Even if the figure of the Jeztyrnaq is not associated with matriarchy, as Qondybai suggests (and modern scholarship does not accept this nineteenth-century idea), the connection with ancient female rituals is obvious.

White Yurt at green mountain valley in Almaty, Kazakhstan/Alamy

The parallel that Qondybai draws between the images of Artemis and the Jeztyrnaq is quite convincing, but I have another hypothesis. The Kazakh Jeztyrnaq’s defining feature is her copper (brass) claws, while the Kyrgyz version, the Zhez tumshuk, emphasizes her brass nose, or more precisely, her beak or muzzle. This focus on metallic features could link the Jeztyrnaq to the bird Samruk (Shyñyrau), which is also described as having metal claws and beak, but I have not found any other arguments in favor of this hypothesis so far.

The Jeztyrnaq’s appearance is described using details that may seem incidental or which perhaps retain mythological overtones: ‘a young woman in a blue dress’, ‘a dress with pendants of silver or iron’, ‘a dress that jingles when she moves’, ‘a tall, gray-black (dark-skinned) woman’. We are told that her sharp nails are made of iron, copper, brass, or gold, that ‘the palms of her hands are of blue-gray iron, like the blade of a knife, and the tips of her fingers are sharp as spears’, that ‘copper is worn on her nails’, and so on. The mergen takes some things from the Jeztyrnaq’s ‘house’, such as her gold and silver buttons, pendants for braids called sholpy, beads, or a white axe.

Taking the abundance of metals in the story and its name into account, we can assume that with the development of metalworking in the Bronze Age, the oldest image of the ‘Lady of the Animals’ was probably superimposed on the image of the ‘Lady of the Ore Deposits’ and the ‘Patroness of the Smith’s Craft’. Perhaps this image was not anthropomorphic from the very beginning, but with time, it took on the image of the Jeztyrnaq known to us. There are also associations with the image of the Mistress of the Copper Mountain in a Russian fairy tale made famous by Pavel Bazhov in the 1930s.

A simurgh (‘anqa') from al-Qazwini's «Wonders of creation». 18th century/Wikimedia Commons

Qondybai considered the myth of the ancient hunter as a whole to be an astral myth: the deserted steppe is the night sky, the animals are the stars, the hunter is the constellation Orion (a particularly fitting association in Turkic mythology since this constellation is associated with the image of the hunter), the aul full of girls is the constellation Urker/Pleiades, et cetera. He writes:

‘Perhaps all these things—gold and silver buttons, pendants for braids known as sholpy, the beads, the white axe—represent certain constellations (or some celestial calendar phenomena or events) in concrete examples, but we cannot claim to have fully understood the symbolism of these things; it is quite possible that unknown meanings are hidden here.’

Qondybai suggested that the Jeztyrnaq in the astral myth may be associated with the Big Dipper constellation (in Greek mythology, the name of the constellation of the Big Dipper is associated with the nymph Callisto, who was a member of Artemis’s retinue) or one of the zodiacal constellations, and that her encounter with the hunter coincided with the winter solstice. The Jeztyrnaq’s trail of blood drops is the Milky Way. The sequence of events—marrying the mergen’s daughter, waiting for the Jeztyrnaq’s daughter, fighting with her, and killing her corresponds to the spring months on the calendar, the time of the ‘descent to earth’ of the Urker/Pleiades.

Elihu Vedder. The Pleiades. 1885/Wikimedia Commons

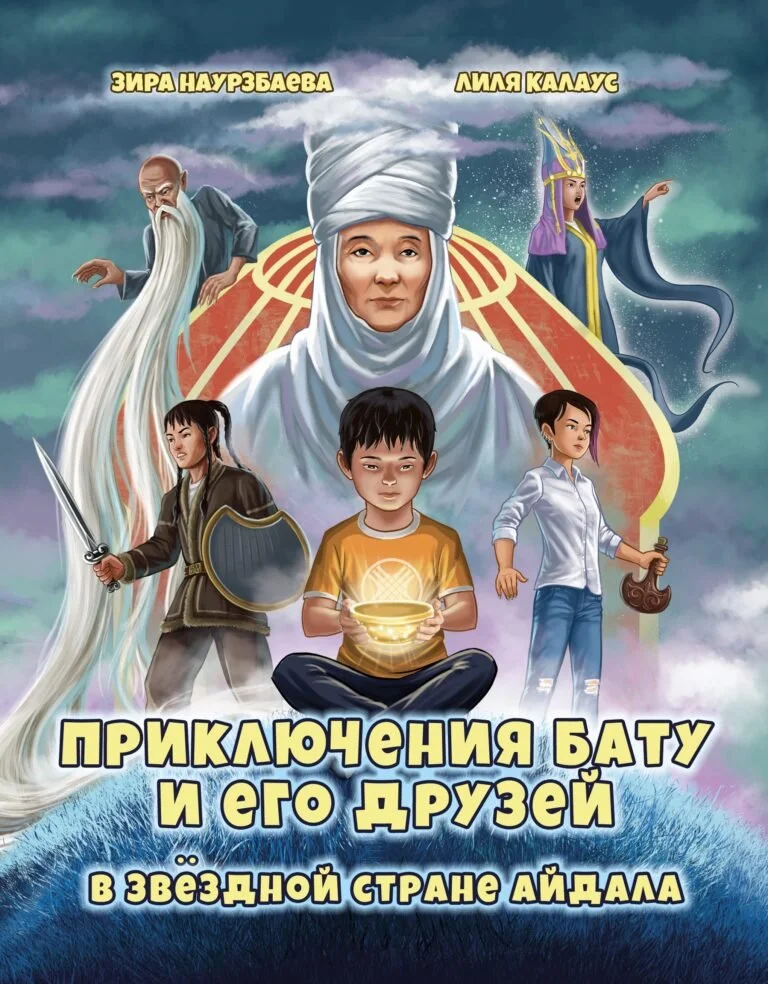

Thus, the figure of the Jeztyrnaq dates back to ancient times. Through this image, it is possible to reconstruct the layers of mythology connected with the myth of the Kulturträger hunter, with the Bronze Age, matriarchy, astral myths, et cetera. The Jeztyrnaq has remained an interesting symbol for the creative imagination as well. About twenty years ago, Talasbek Äsemqūlov wrote a parable screenplay titled Jeztyrnaq, which won an international competition of scripts based on myths, fairy tales and heroic epics of Central Asia and Korea in 2011. In this work, the Jeztyrnaq appears outwardly bloodthirsty, but in reality, she judges people in terms of absolute morality. In my children’s story ‘The Adventures of Batu and His Friends in Search of the Golden Bowl’ (2005, published in 2014), written with Lilya Kalaus, the evil Jeztyrnaq is transformed into the bird Samruk in accordance with one of my hypotheses about this symbol. Indeed, several other works in this spirit have appeared in recent years, such as the comic strip Jeztyrnaq by the young artist Mağira Tleuberdina, suggesting a broader trend of reimagining these symbols in contemporary art and literature.

The adventures of Batu and his friends in the star lands of Aidala/otuken.kz