The Color of Power and Vice

The story of the Yellow River, the yellow emperor, and pornography

Flag of China (1889-1912)/Wikimedia commons

The color yellow has always had a special place in Chinese culture. Unlike Western countries, where yellow may sometimes have represented cowardice, the color has been associated with power, prosperity, and prestige in China for millenia. So why did the Chinese treat it with so much respect? Let’s find out!

The Yellow River, or the Huáng Hé River, is often called ‘the mother of all China’ because the Chinese civilization had its origins in the central part of its basin, on the fertile Loess Plateau formed from sediment deposits. And this is not mere legend; Chinese archeologists found the ruins of a large city dating back at least 5,300 years in the central province of Henan, about 2 kilometers south of the Yellow River.

It is possible that this very ancient city was once ruled by the mythical first emperor of China, Huangdi, who is also sometimes called the Yellow Emperor. Huangdi, believed to be the creator of Taoism—a highly respected philosophy in China, where ‘the Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao’—is considered to be the forefather of all Chinese people.

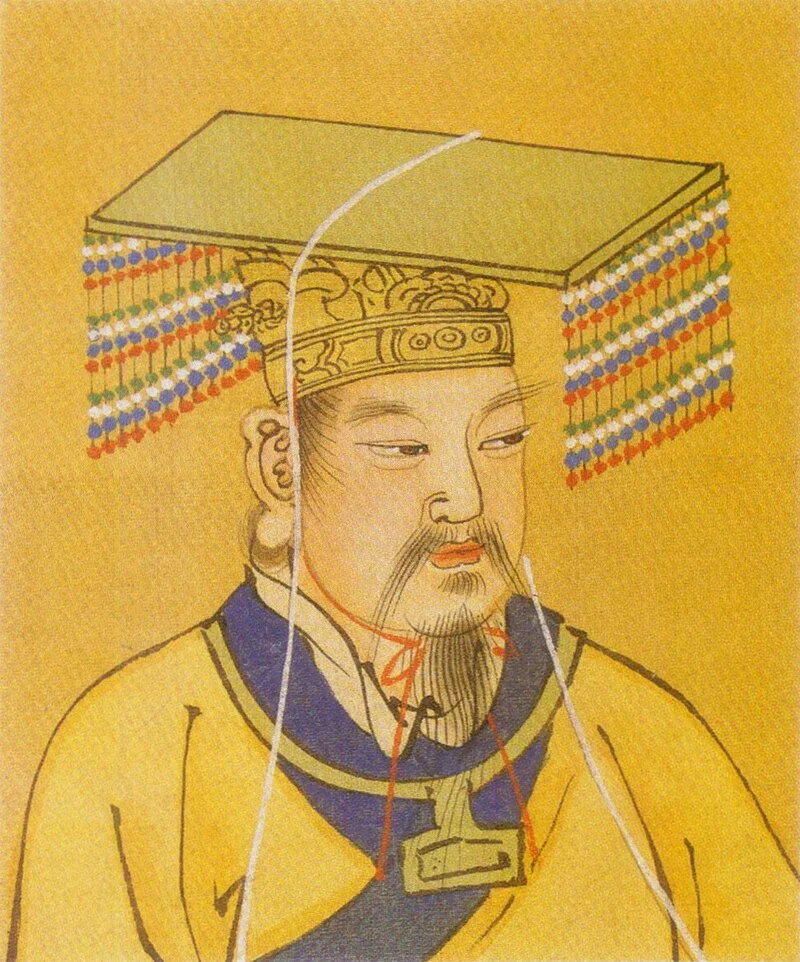

We do not know when he lived and whether he ever lived at all. The image we have of him is somewhat similar to that of one of the Greek Titans, Prometheus, who brought fire to humanity and taught people to cook food and use fire to make amazing things. Indeed, many inventions that changed the fate of humankind are attributed to Huangdi. He taught people how to build carts, boats, and wooden houses. He invented many things, from the throwing wheel to writing, the calendar, and even the bamboo flute. It is not surprising then that in Chinese literature about time travelers who accidentally find themselves in the distant past, many of them become Huangdi after their adventures.

Yellow Emperor /Wikimedia Commons

Why was Huangdi known as the ‘yellow’ emperor? The reason for this is that Chinese people associate a whole array of ideas with this color. In China, yellow was the main color and had the meaning of earth within the five phases philosophy of Wuxing,i

What is even more important is that in the Chinese language, a clear division between the words ‘yellow’ and ‘gold’ never took place as it did in many other languages. In Russian, these words have the same origin, and in many Germanic languages, the words for the two colors are very close.i

Yellow Crane Tower, view of the interior and ceramic mural. Wuhan, China/Alamy

For the Chinese, ‘yellow’ (黄, huang) means ‘gold’ (金黄, jin huang, yellow metal). When in other languages people talk about having a golden heart, the golden age or the golden days, the Chinese use the word ‘yellow’ instead. It would be more correct to translate the emperor’s nickname as the ‘Golden Emperor’, but historically it didn’t quite work out that way.

For centuries, it was believed in China that only the emperors or nobles had the right to wear yellow clothes and accessories and common people were forbidden to do so under the penalty of death.

IMPERIAL YELLOW JAR. (Kuan), nine inches high without the cover, enameled with a monochrome glaze of imperial yellow. Made in the reign of K'ang-hsi (1662- 1722), of the great Ch'ing dynasty From the book ' ORIENTAL CERAMIC ART COLLECTION OF William Thompson Walters ' Published in 1897/Alamy

This exclusive association with royalty is evident in one of the biggest Chinese peasant revolts that took place in the second century CE known as the Yellow Turban Rebellion. The rebels wore headwear of the forbidden yellow color, intending to demonstrate that they would stop at nothing in order to overthrow the hated government of the Han dynasty. The rebels claimed that following their victory, ‘the blue sky of evil’ would be replaced with the ‘yellow sky of justice’. The unrest lasted for nearly twenty years and in the end, everyone lost—the rebels, who were cruelly destroyed, and the government, which was for some time split into three independent kingdoms.

But still the bright, saturated yellow remained the forbidden color of the emperor.

In the Chinese court, the emperor’s yellow gown had the same significance as a crown at the courts in Europe, and Chinese legends exemplify this perfectly. The emperor Zhao Kuangyin (927–976), founder of the North Song dynasty, was a military leader who gained power as a result of a military uprising. During the uprising, the soldiers and officers burst into Zhao Kuangyin’s quarters and almost forcefully dressed him in the gold embroidered yellow gown, proclaiming him the new emperor.

Portrait of the Hongwu Emperor in a silk yellow dragon robe embroidered with the Yellow Dragon/Wikimedia Commons

The Qing Dynasty (1636–1911) only solidified the connection between yellow and imperial authority. During the rule of this dynasty, the emperor, as recognition of merit, gave government officials yellow magua jackets (a jacket that was worn over their other clothes). Bodyguards had the right to wear yellow magua jackets only when on duty.

The significance of yellow is not limited to clothing. The carriage used by the emperor was called the yellow house, the road the emperor walked on was the yellow path, and the flags that were raised above the emperor during inspection trips were also yellow. The seal of the dynasty was wrapped in yellow cloth, and only the emperor had the right to live in buildings with red walls and yellow roof tiles. These buildings can still be seen in the Forbidden City in Peking.

The Forbidden City of Beijing, China /Shutterstock

‘Today, the color yellow still symbolizes ancient China,’ writes Ma Lee from the Belarusian State University of Culture and Art in their article ‘Symbolism of Color in Chinese Art’. Yellow is used in painting to express joy, light, respect, and hope and to symbolize openness, glory, and ambition. Artists also often use yellow to emphasize grandeur and wealth.

Yellow Dragon Ceramic Decoration Symbol Emperor Red Wall Gugong, Forbidden City Emperor's Palace, Beijing, China/Alamy

In an article titled ‘Cultural Connotations of the Color Yellow in Chinese Culture’, Yan Hayun, doctor of historical sciences at Tianjin Normal University, and his PhD student Lu Juhuei explain that there are seventy-six idioms containing the word yellow in the Big Idiom dictionary and the Big Chinese Idiom dictionary. The word ‘yellow’ in these idioms has these main meanings:

1) A symbol of happiness and success:

-

To become an emperor or gain victory: ‘To put a yellow gown on someone’ (huang pao jia shen)

-

To quickly rise and become successful: ‘The yellow-winged horse rose up and made it to the destination’ (fei huang teng da)

2) A symbol of longevity:

-

An old person: ‘Yellowing hair and spotted back’ (huang fa tai bei); ‘yellow hair and child’s teeth’ (huang fa er chi)

3) A symbol of integrity:

-

To have high integrity in old age: ‘Old age and yellow flower’ (wan jie huang hua)

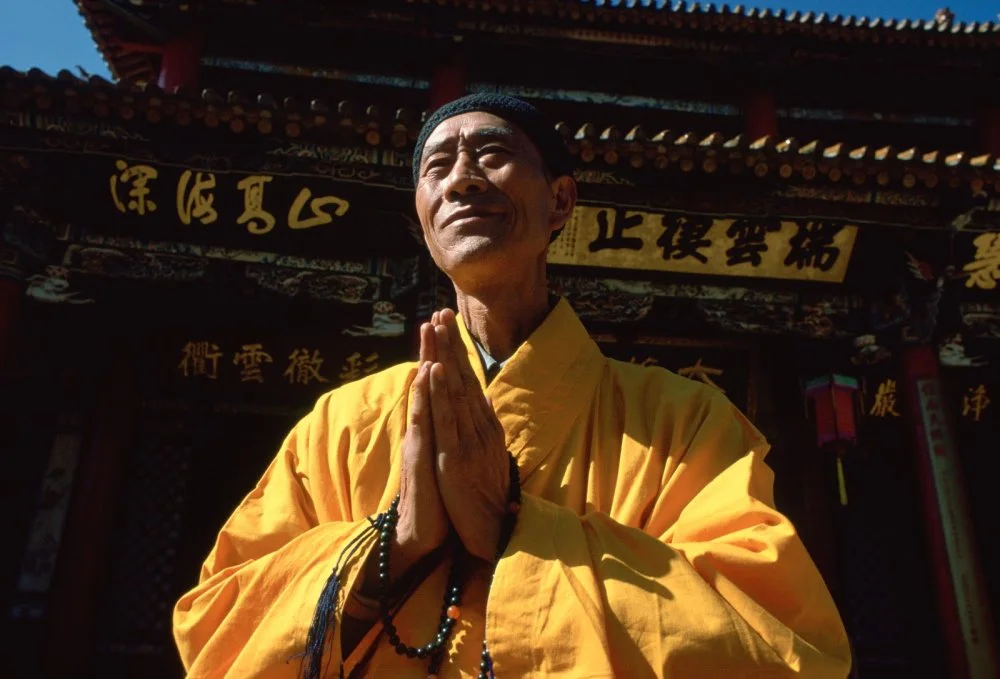

In Buddhism and Taoism, yellow is a symbol of holiness, godliness, and solemnity. The clothes of Buddhists, especially those belonging to the Tibetan school of Gelug, are yellow. This is probably why in the Mongolian-speaking world, Buddhism is often called the yellow religion.

A Buddhist monk in saffron coloured robes with hands together while praying at the Buddhist Temple in Huating, China/Tim Graham/Getty Images

But the meanings of these yellows are not all that simple. As Yan Hayun and Lu Juhuei point out, the hieroglyph 黄 (yellow) in China has several other meanings which are usually used in everyday speech:

1) A symbol of bad luck:

-

‘This business has turned yellow’ (zhe jian shi huang le), which means that a business or plan has fallen through

2) A symbol of death:

-

‘Yellow spring’ (huang quan), which means the afterworld

3) A symbol of ill health:

-

‘Yellow face’ (huang lian), which means to have an unhealthy look

4) A symbol of immaturity:

-

‘A girl with yellow hair’ (huang mao ya tou), which means a young, immature and inexperienced woman

5) A symbol of pornography:

-

In modern China, the color yellow is often associated with pornographic materials. For example, ‘yellow picture’ (huang tu) means a pornographic image, and ‘yellow book’ (huang shu) is a book of a similar nature. Police banners stating ‘To clean the yellow’ (sao huang da fei) mean to attack vice, like, for example, when the Chinese police carry out raids aimed at pornographic content sellers and sex workers.

A police raid in China/Photo by Luo Yunfei/China News Service/VCG via

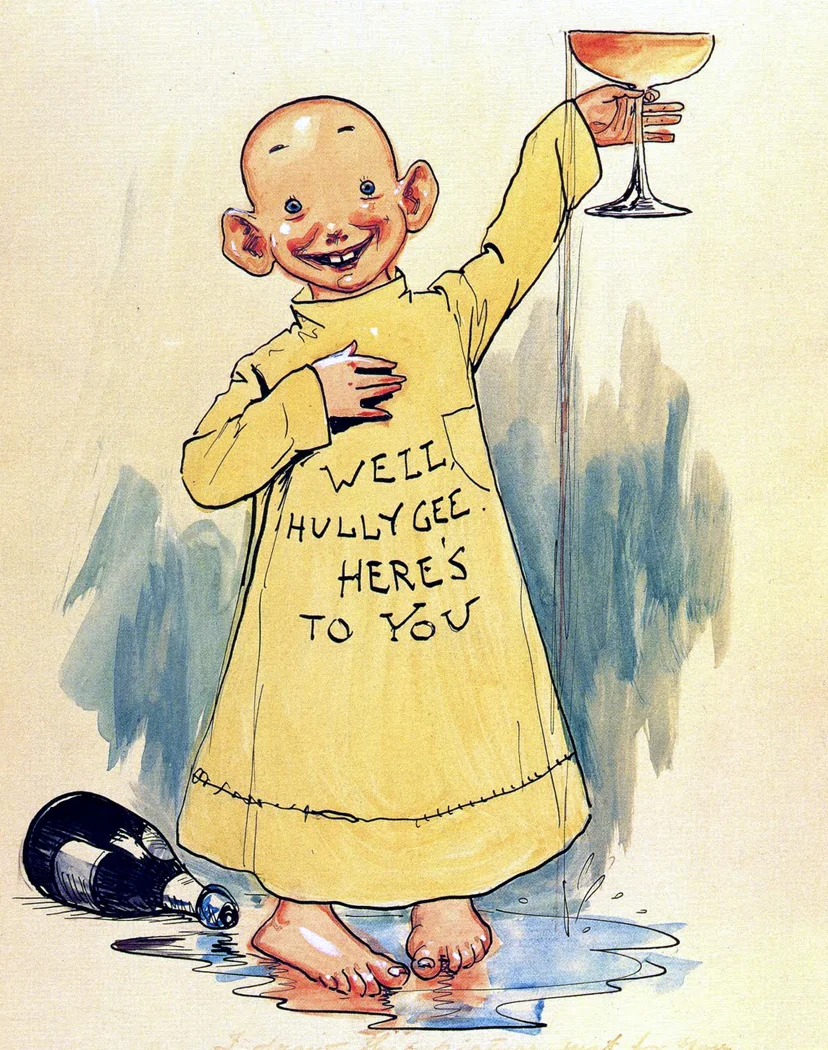

How the color might be used to reference death and illness is pretty clear—take, for example, the ‘yellow’ afterworld of ancient China. But how did this word transition to the world of pornography? How did the sacred color of emperors acquire such a sinister meaning in China? Perhaps this change can be attributed to Western culture with its ambiguous attitude to yellow, with terms such as ‘yellow house’ (a mental institution) or ‘yellow press’ gaining popularity.

The term 'yellow journalism', coined by journalist Ervin Wardman at the start of the twentieth century to describe newspapers that thrived on unverified sensational news, spread worldwide and did not spare the Middle Kingdom. This term was first put into a dictionary in China in 1936, and the meaning of the phrase was ‘low-quality publications that attract readers partial to scandalous news and low-rate sensations’. Eventually, the word yellow started being used in relation to pornographic literature, newspapers, films, and TV series.

The Yellow Kid, drawn by Richard F. Outcault, appeared first in Pulitzer's New York World and then moved to Hearst's New York Journal 1897/Wikimedia Commons

Not so long ago, one of the head government deputies of the Hainan province Lyn Fanlui expressed his outrage about this association: ‘It is a disgrace for the Chinese as the descendants of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi) to associate the color yellow with pornography. It is important to remove the expression “liquidation of yellowness and fight against unlawful acts” from the spoken language and official documents and replace it with “liquidation of pornography and fight against unlawful acts”.’ However, his appeal has not yet received any response.

CHINATOWN BANGKOK THAILAND - 01/05/2019 : Very crowded tourist sightseeing at China town ''Yaowarat"" road famous street food market and wonderful night light/Shutterstock