A. L. J. I. R. — this is how the prisoners called the Akmola camp for the wives of traitors to the motherland, located in the middle of the Kazakh steppe. Widows and children of those executed during the Great Terror in 1937 served their sentences here. Especially for Qalam, journalist Sergey Nikolaevich collected eyewitness accounts of how life was arranged in the largest women's prison in the USSR.

Today, he is the last one remaining. He speaks of himself with a wistful smile as he says,

‘I am the last prisoner of ALZHIR.’

Azari Mikhailovich Plisetski, the renowned dancer, ballet teacher, and younger brother of the great ballet dancer Maya Plisetskaya, turned eighty-six this year. He entered the Akmolinsk Camp for Wives of Traitors to the Motherland (a translation of its Russian name ‘Akmolinskii Lager Zhen Izmennikov Rodiny’), also known as ALZHIR, when he was barely a year old. It was there that he learned to walk and there that he uttered his first meaningful sentence:

‘I want to go outside the zone.’

For him, memories from that time are undoubtedly quite vague. Most likely, they come from his mother, Rachel Mikhailovna Messerer-Plisetskaya, who did her best to shield her son from the negativity. She did not want him to become bitter or harbor hatred towards the Soviet authorities, who had taken away his father and almost destroyed her life.

In ALZHIR, silence became the primary condition for existence, the only chance to preserve oneself and survive. The victims of the Gulag learned this rule above all others. Perhaps that's why they remained reserved for the rest of their lives, long after they left the camp. That’s also perhaps why detailed memories of and the first honest interviews about life in the camp only began to emerge during the peak of Gorbachev's perestroika. It was then that many first heard the strange name ALZHIR, not at all related to the name of a distant country in Africa.

ALZHIR was situated not that far from Moscow, but it occupied a distinct latitude characterized by perpetual permafrost, feather grass, and the vast expanses of the Kazakh steppe. The winter brought the temperatures down to -40 degrees Celsius. In summer, scorching heat and blazing sun. The official opening date of the Akmolinsk Camp for the wives of traitors to the motherland was preserved in documents as 3 December 1937 and was abbreviated as ALZHIR.

THE FATE OF WOMEN IN ALZHIR

Concentration camps for women and children—Temnikovskiy in Mordovia, Dzhangizhirskiy in Kyrgyzstan, Temlyakovskiy in the Gorky region—were organized in advance by the order of the head of the Gulag, Matvei Berman, in a ciphered telegram dated 3 July 1937:

‘Soon, those sentenced must be condemned and isolated under particularly stringent conditions. The families of executed Trotskyists and right-wingers (...), predominantly women, should be included. Preschool-age children will also be sent with them.’

The Soviet authorities were preparing in advance to make mass arrests and deportations. Everything was very clearly laid out, and as per the instructions in NKVD Decree No. 00486 (15 August 1937): ‘An investigative case is to be initiated for each arrested person and each socially dangerous child over 15 years old. Infants will be sent together with convicted mothers to camps and, after reaching 1–1.5 years of age, they will be transferred to orphanages and nurseries. If relatives (unrepressed) wish to take orphans under their full care, it should not be hindered.’

Data on the ‘removal of the children of the enemies of the people’ to ALZHIR and other camps is available for January 1939, involving a total of 25,342 individuals. Of these, 22,427 children were sent to the orphanages of the People's Commissariat and local nurseries. Some other children, numbering 2,915, were placed under guardianship and returned to their mothers. This is just the data for the first seventeen months after the decree on wives and children of the repressed was issued—from 15 August 1937 to January 1939.

Data on the ‘removal of the children of the enemies of the people’ by January 1939 involved a total of 25,342 individuals.

These lists do not include ‘socially dangerous’ children who were more than fifteen years old. The exact number of infants sent to the camp with their mothers or born in it during the years of terror, also known as the Great Purge, is not recorded. The scale of this tragedy begins to be realized only here, at the site of the former Camp Point No. 26, which houses the only memorial to the deceased and tortured victims—women and children of the Gulag, the unfortunate 'Alzhirians', as they were commonly referred to.

SEPARATING HUSBANDS AND WIVES

Ekaterina Ivanovna Kalinina, the wife of the All-Union Chairman, a member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) since 1917, and a member of the Supreme Court of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), was considered the most distinguished prisoner of ALZHIR. Her case was complicated—on the one hand, she was a family member of a traitor of her country, and on the other, she faced two capital charges: ‘Espionage’ (Article 58–6) and ‘Committing terrorist acts’ (Article 58–8) as listed in the RSFSR Penal Code.

Meanwhile, her husband, Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin, was not only not arrested but also continued to faithfully perform his duties as the nominal chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR after her arrest. He appeared on the tribune of the Lenin Mausoleum during holidays and awarded orders of merit to particularly distinguished individuals in the field of building socialism. One theory suggests that Stalin maintained tight control over his closest associates by imprisoning their wives, essentially conveying the message, ‘Challenge me at your own risk, knowing that your wives are already in prison.’ Later, the long-standing Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov would also be subjected to this humiliation. His wife, Polina Zhemchuzhina, a prominent stateswoman and leader, joined the ranks of the Gulag prisoners after the Second World War.

Opera singer Olga Mikhailova, the wife of the legendary marshal and Red Army cavalryman Semyon Budyonny, was charged with espionage. There is also information that a case was initiated against Kliment Voroshilov's wife, Yekaterina Davidovna. But the marshal demonstrated his character when officers from the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (Naródny Komissariát Vnútrennih Del (NKVD)) came to his house with an arrest warrant. He drew his service pistol and threatened to shoot. The NKVD officers quickly retreated, and the case against Yekaterina Voroshilova was withdrawn.

But her namesake Yekaterina Kalinina was much less fortunate as historical records indicate that during interrogations at Lubyanka Street, which was the headquarters of the Cheka or the secret police, she was subjected to torture. The case protocols recorded that the suspect could not walk to the interrogation on her own, and she was carried. It was not surprising that after all the torture she had endured, she had admitted her guilt without any evidence or proof, and her influential husband could do nothing. The only thing he dared ask for was for Yekaterina not to be burdened with hard physical labor.

She spent seven years of the fifteen that she was sentenced to in ALZHIR. She was listed as a castellan, whose duties included removing lice from prisoners's laundry. She lived in a pantry next to the laundry for all those years, which was considered a far more privileged existence than living in a typical barrack on a sleeping shelf. Shortly before Kalinin's death, he turned to Stalin with a humble request to release his wife.

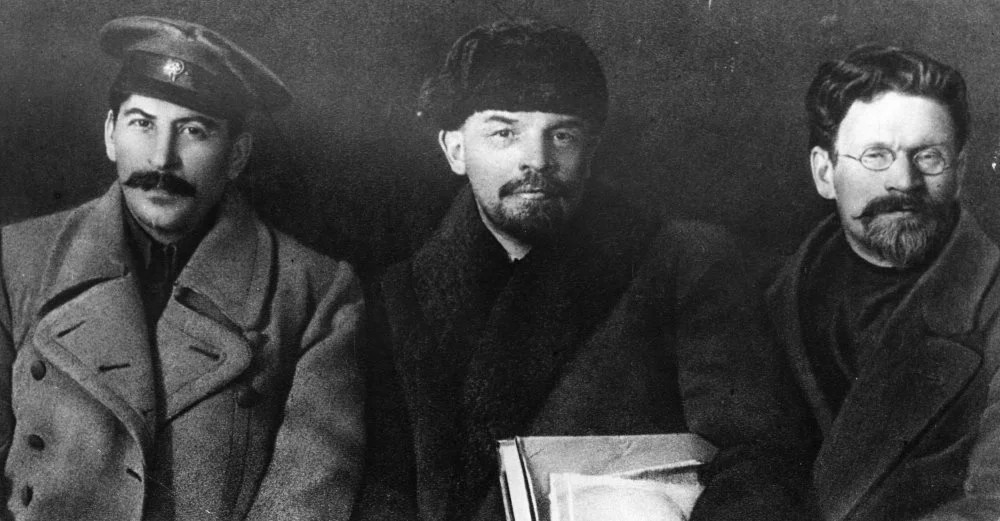

Joseph Stalin, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin. Congress of the Russian communist party/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

However, the ‘highest pardon’ did not delight her at all. She categorically refused to sign a petition for clemency to Stalin, as was required for her release. In the end, her sister came to the camp to convince the obstinate Yekaterina to fulfill all the necessary formalities for her own release. After this, however, they hardly crossed paths with Kalinin in Moscow. He was already very ill, with no more than a year left to live. She tried to avoid meeting him, rightly believing that he’d had the opportunity to save her much earlier but chose not to. However, could he really have? This question remains unanswered to this day.

‘THERE, THEY'LL FIGURE IT OUT’

In all, 20,000 female prisoners passed through ALZHIR while it was operational. They were primarily the wives of state and party officials of various ranks, military personnel, NKVD employees, leaders and specialists of large enterprises, and well-known figures in science and culture. They were usually arrested in broad daylight or late at night, often right at their workplaces, and sometimes even during the intermission at the theater. They were hardly given time to gather themselves, and many of them went to the camp in high heels and evening gowns.

One of the common illusions in the camp was that socialist justice would surely prevail, that 'There, they'll figure it out.' They believed that the authorities at the camp would figure out whether they were truly guilty or not. The awakening, however, did not come immediately. After endless nights of interrogations, the prison stench, and darkness after a hasty sentence, it became clear that there was no salvation to be expected from anywhere.

Throughout its history 20,000 women were imprisoned in ALZHIR.

Maya Plisetskaya's memoirs contain a description of her father's arrest: ‘Unknown people. Rudeness. A search. The whole house turned upside down. Crying, clinging, pregnant with a full belly, my disheveled mother. My little brother crying, awakened from sleep. My father, dressing with trembling hands, as white as snow. It was awkward for him. Detached faces of neighbors. The unkempt, overly familiar Varvara, the janitress, with a lit cigarette in her teeth, not missing a chance to ingratiate herself with the authorities (“I wish they would shoot all of you, you damn scoundrels, enemies of the people!”) ... And the last thing I hear from my father before the door slams shut forever: “Thank God, there they'll finally figure it out …”’

Until 1956, nothing was known about the fate of Mikhail Emmanuilovich Plisetsky, though he was executed on espionage charges on 8 January 1939. His children were told that their father had disappeared without a trace on the front. Rachel Mikhailovna fervently believed that her husband would definitely return, a conviction that endured until she received a certificate from the prosecutor's office. It can be said that this hope warmed her soul through her life. According to Azari’s memories, Rachel had always looked for signs from above that her husband was alive. For example, once, when she found chocolates named Bear in the North in a parcel sent to her from Moscow, she saw a secret message in them: her Misha was in some camp in the north.

‘Father was taken in April 1937, and I was born in July,’ recalls Azari Mikhaylovich Plisetski. ‘Soon after my birth, they called my mother; we lived on Gagarinsky Lane at that time and an unfamiliar voice on the phone said, “Don't ask questions, just say who you gave birth to.” My mother replied “A son,” and the connection was cut off. When I reconstructed the chronology of events, I understood that it was when they were interrogating my father, demanding some confessions from him. And the investigator called to get them in exchange for the call.’

Six months later, they came for his mother, Rachel Messerer. More precisely, she was arrested with her six-month-old son. At first, they were taken to Butyrka. There, she was given a choice: either she signed statements against her husband and wrote a written disavowal of him, after which she would be free, or her children would be taken to an orphanage for the children of repressed individuals, and she herself would be sent to the ALZHIR camp. Rachel refused to sign a denunciation against her husband. As a result, after several months of detention, she was handed her sentence: eight years for being the ‘wife of a traitor to the motherland’.

Wall of Remembrance with the names of women who spent their time in the ALZHiR camp. Astana, Kazakhstan/CTK Photo/Alamy Live News

THE ROAD TO AKMOLINSK

The prisoners arrived at the camp in a cattle car ventilated by a palm-sized window covered with a grate. They were all sorted, and Rachel found herself among a crowd of ‘traitors’, many with infants. The car was packed to capacity—there was no room to sit or turn. The toilet was a hole in the floor. The train moved slowly, stopping at every station. The guards clanged the locks, vigilantly ensuring no one escaped, maintaining strict control. Today, one of these ‘cattle cars’ (as the wagons for transporting prisoners were known) is a key exhibit in the ALZHIR museum. All that remains is charred wood, cramped quarters, rusty locks.

A poem by the famous poet Anna Akhmatova summarizes the women’s experience of getting to ALZHIR perfectly:

A Stalin-era carriage for transporting prisoners/Mikolaskova Lucie/CTK Photo/Alamy Live News

‘Ask my contemporaries –

Convicts, hundred-and-fivers, prisoners –

And we will tell you,

How we lived in unconscious fear,

How we raised children for the executioner,

For prison and for the torture chamber.’

Miraculously, Rachel Messerer managed to pass a short note on a piece of newspaper with her sister's address, containing just a few words:

‘Heading towards Karaganda, to the camp. Child with me.’

Also, as Maya Plisetskaya later recalled, her mother saw a young woman in a railway worker's uniform with a railroad flag in her hand in the window at a desolate crossing where the train briefly stopped. Their eyes met. With a precise motion, Rachel tossed a crumpled piece of her paper to the woman's feet. The switch woman pretended not to see anything. Then the train moved again.

LIFE IN THE CAMP

The first stages of building and populating ALZHIR began in January 1938. Trains from Moscow, Orenburg, Irkutsk, Rostov, Kaluga, and Orsh halted in the barren steppe amid -40 -degree Celsius frosts. Six barracks made from adobe bricks, capable of accommodating 250–300 people each, were erected. In addition, a few small houses for the guards and leadership were built and designated accordingly. The upper level of the barracks had a window without glass, which was filled with rags to keep out the cold. Near the exit was a partitioned area with a long sink.

The barrack where the women prisoners lived/Mikolaskova Lucie/CTK Photo/Alamy Live News

Water for washing and cleaning was provided once a week despite Lake Zhalanash being within the camp zone.

Maria Antsis, the widow of the secretary of the Krasnolugansk regional committee of the Communist Party, described her arrival vividly in her memoirs:

It was getting dark. We were led into the area under escort, fenced with barbed wire. Guard towers are visible on the sides and in the distance, and the barking of dogs guarding the zone can be heard.

Squinting, we walked four abreast, accompanied by a special escort holding rifles at the ready. A large number of guards with dogs brought up the rear. None of us looked back (as the guards warned us not to).

The women held in the Akmolinsk special unit were documented as ‘particularly dangerous’, resulting in particularly harsh conditions for them. For the first year, they were deprived of letters or parcels from home and denied visits, living under a strict isolation regime. The compound walls had triple rows of barbed wire, and roll calls were conducted twice daily. Reading and keeping any records were strictly prohibited. Stalin's implicit directives were to see these women as more than simply wives. They were seen as the spouses of the 'chief enemies', the 'right-Trotskyist' conspirators.

Exhibit of the ALZHiR Museum / From open access

In modern terms, these women represented the elite that had emerged in the first two decades of Soviet power and governance. However, by the mid-1930s, Stalin began to view them as internal opposition and a constant threat. His observations of the lives of underground revolutionaries at the beginning of the century suggested that wives would always support their husbands, making them, in his mind, accomplices to the crimes of their spouses.

Strictly speaking, no court proceedings were held for women or the other relatives of ‘traitors to the motherland’. The recommended sentences were outlined in Directive No. 00486, and women were merely informed of the decisions made at Special Meetings at the NKVD.

Unfortunately, accurate data on the total number of women repressed as ‘family members of traitors to the motherland’ (abbreviated as FMTM in NKVD documents) has not been established to this day. Among the sources available to historians is a memorandum from Nikolai Yezhov, the head of the NKVD from 1936 to 1938, and his deputy Beria to Stalin on 5 October 1938:

According to incomplete data, more than 18,000 women of arrested traitors have been repressed, including over 3,000 in Moscow and about 1,500 in Leningrad.

LABORING THROUGH THE DAYS

One of the most famous lines forever etched in the chronicles of ALZHIR is

‘Where else would I encounter such high society!’ This remark is attributed to the beauty Kira Andronikashvili, the wife of writer Boris Pilnyak. She was the closest neighbor of Rachel Messerer and Ashkhen Nalbandyan (the mother of the future poet and writer Bulat Okudzhava) in the barracks. Indeed, it was an exceptional set of women to be around. Elizabeth Arvatova-Tukhachevskaya, the sister of the executed marshal Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky, served as the cook in the canteen. Along with them in the barracks were Eugenia Lurie-Trifonova, the mother of the writer Yury Trifonov; Lidia Bagritskaya, the wife of the poet Bagritsky; and Galina Serebryakova, the widow of Lenin's favorite, Nikolai Bukharin. As one of the camp guards once proudly recalled, ‘We had 250 pianists alone!’

However, the expertise and knowledge of most prisoners were in no demand. Agronomists, draftswomen, estimators, and tailors were needed for camp work. All the others were sent to gather reeds from the shores of Lake Zhalanash, which were used to heat the icy barracks. The prisoners had mostly started arriving in the winter, and their chances of survival depended on how well the heating worked. A prisoner named Maria Antsis describes the strenuous labor in the following manner:

‘The sound of shovels hitting the ice, which encased the reeds, echoed across the steppe ... In the first moments, despair gripped us. But each of us, feeling the presence of a companion's elbow, gradually pushed away fear, and the pliable reeds turned into large, heavy bundles. Some comrades proposed dividing our work into several stages: the stronger women compacted the reeds, the others made bundles, the third group bound them, and the fourth carried the bundles to the piles. Thus, the division of labor in large quantities emerged in reed harvesting ... The command “Line up!” spread throughout the entire lake. Each of us, loaded with four bundles, joined a group of four, and the procession headed down the already beaten path to the camp ... The work on the lake took the whole day. After a ten-hour shift, we were exhausted, and our eyes hurt from the dazzling snow. It seemed to us that if we were allowed, we would just lie down on the bundles of reeds and not open our eyes.’

According to NKVD order No. 276 (13 August 1937), prisoners were exempted from outdoor work at temperatures below –30 Celsius degrees. Moreover, they were entitled to the use of carbolic vaseline for their hands and faces. However, this order was practically never enforced, and in February 1938 alone, eighty-nine cases of severe frostbite were recorded in ALZHIR.

The spring and summer didn't bring any relief as the imprisoned women had to design and build workshops for a sewing factory and new barracks for the new prisoners arriving in stages. They worked 112 hours a week. No one tried to get exemptions from work, and there were no recorded escape attempts. Where could they run? There was only the vast steppe all around them. The administration reported on socialist competitions involving top-performing workers, scheduled to coincide with 8 March, the anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution.

An installation of camp life. ALZHiR museum/From open access

However, on holidays, all the prominent workers were confined to barracks with increased security to prevent them from organizing a rally or any kind of demonstration. They were also escorted to the canteen under guard.

Those not involved in building barracks and workshops were sent to do heavy agricultural work. The women dug ditches, carried water, and planted fruit trees. At the experimental horticulture station, new seed varieties were bred for the first time, and cucumbers, tomatoes, cabbages, and onions were grown in the steppe. Soon, under the guidance of experienced agronomist Galina Rudenko, a blossoming oasis emerged in the waterless and arid steppe.

A prisoner named Ksenia Maltseva said of the experience:

‘To begin with, we plowed eighteen hectares of land to plant vegetables, and everything was done manually with shovels. I was the irrigation brigade leader, waking up at 4 a.m. when everyone was still asleep and returning late at night. We worked for fourteen to fifteen hours per day without weekends. We grew carrots, tomatoes, and fruits.’

However, this abundant harvest had no impact on the meager diet of the prisoners; a stolen onion bulb could easily lead to several days in solitary confinement. Just like the products of the sewing workshops, all the vegetables and fruits grown by the women were taken out of the camp. It is even more astonishing to hear the admission of the former silent film actress Lydia Frenkel, who was imprisoned at ALZHIR:

‘When I wheeled a barrow, lifted straw, or worked in the garden, I did everything with full force. I vividly remember how the housewives laughed at me:

“Why are you straining yourself like that? What did the state ever give you? Stop doing it, take it easy.” I don't know why we put so much effort into it. But there was no other way for us.’

A LULLABY FOR THE CHILDREN OF THE ENEMIES OF THE PEOPLE

The primary challenge for most women inmates at ALZHIR, however, was not the heavy, exhausting labor or the harsh living conditions. Instead, it was the thoughts that haunted them about the fate of their children—those left behind and those who, because of their young age, were allowed to accompany them to the camp. Only a few managed to place their children with relatives. For instance, Kira Andronikashvili, after her husband Boris Pilnyak's arrest, sent her three-year-old son, Boris, to her sister, the famous actress Nato Vachnadze, in Georgia. Rachel Messerer-Plisetskaya's older children, Maya and Alexander, were taken in by her sister Sulamif Messerer, a Bolshoi Theatre ballerina, and brother Asaf Messerer. To ensure that their nephews did not go to an orphanage, they officially adopted the boys. Otherwise, they would be ‘restricted’ in their rights and wouldn't even receive a basic education. However, these examples are more of an exception than the general rule. In most cases, the children of ‘traitors to the motherland’ went to special orphanages and, in most cases, endured a change of surname. This was done to ensure that they wouldn't even have memories of their parents.

Installation, removal of the child from the mother. ALZHiR museum / From open access

The fate of those children born in ALZHIR was even more tragic. According to official data, from 1938 to 1953, 1,507 children were born in the camp. This statistic includes only those who survived because infant mortality was high. Nearly every month, approximately fifty children would die. During winter, they were not buried because it was impossible to break the perpetual permafrost and so, the bodies were placed in barrels until spring. There are heart-wrenching memories from Valentina, a local nurse who worked for the NKVD, as she passed by these barrels and saw a little arm moving. She pulled out a tiny Kazakh girl, took her home, and, for eight years, raised her as her own daughter. When the mother's prison term ended, she returned the child.

According to the law, children over the age of three were taken from their mothers and transported to orphanages. It's important to remember that during the Great Purge, the Gulag constituted the overarching system of labor camps throughout the Soviet Union. Karlag specifically refers to a set of camps situated in present-day Kazakhstan, with ‘Kar’ representing Karaganda, a province in Kazakhstan, and Lag standing for lager, or camp.

In the documentary Longer than Life (2013, directed by Daria Violina and Sergey Pavlovsky), the memories of Maya Klyashtornaya, the daughter of Belarusian poet Todor Klyashtorny, who was shot in October 1937, were heard for the first time. She ended up in ALZHIR, like Azari Plisetski, at the age of four months. She grew up in the camp and later in the Karlag orphanage. She described the experience of moving as:

They started loading us onto a truck, and we were screaming. The truck started moving, and mothers were running after us. We screamed with all our might. Then the truck stopped: apparently, there was an order from the director, and the mothers ended up in the truck with us. Each one had to say something to her child and give them something, so they gave us handmade toys. My mother gave me a little bunny and a little sailor, saying, “He will protect you.” I was happy to have such toys now. Then we rode to Osakarovka, and we understood that now we would live alone, without our mothers ... We were friends, holding hands. Rida Ryskulova stood out the most. One of the happiest moments of childhood that I still remember was when Rida Ryskulova's mother came to Osakarovka. She spent three days in our barrack, and every evening, she sang us a lullaby before sleep. It was so beautiful. A human, after all, is the sum total of the emotions they experience. No one ever sang us a lullaby. It was a shame to fall asleep to that lullaby, a pity to fall asleep and miss out on one's happiness.

A MIRACLE FOR THE CHOSEN ONES

In reality, Rida Ryskulova's mother’s visit to the Karlag orphanage, along with the easing of the inmates’s labors, became possible only after 21 May 1939, when the NKVD issued Order No. 00577. Classified as ‘secret’ and concerning the ‘Elimination of Special Departments in the ITL’ (the correctional labor camps (CLC) were known in Russian as ITL), the order stated that the ‘entire contingent of prisoners from the specified special departments of the camps should be transferred to the general camp regimes.’

For the ALZHIR prisoners, this meant permission to receive letters and even meet with their loved ones. Galina Stepanova-Klyuchnikova describes these initial changes very vividly:

‘A year of strict restrictions passed—no letters, parcels, or news from the outside world. And suddenly, an unusual event stirred the whole camp. One of the “Algerians” received a genuine letter with a stamp and a postmark. The envelope in a child's handwriting read: “City of Akmolinsk. Prison for moms.” An eight-year-old girl wrote that after her father and mother were arrested, she was also arrested and placed in an orphanage. She asked when her mother would return and take her home. She complained that she was unhappy in the orphanage, missed her mother a lot, and cried often.’

Despite the minor content of this first letter, it instilled a timid hope in the prisoners. Around the same time, the arrival of Sulamif Messerer, a decorated soloist from the Bolshoi Theatre, at the camp became a sensation. Her meeting with her sister Rachel took place in the presence of guards, but the mere opportunity to see a free person and converse with them was perceived as a gift of fate. According to Azari Plisetski, his aunt came to ALZHIR with a clear plan. At the very least, she wanted to ensure that her sister's camp term would be replaced with exile. In the best case, she aimed to bring Rachel back to Moscow with her son. If that couldn't be achieved, she planned to take Azari when he turned three and continue the fight for her sister's release.

Rachel's brother Asaf Messerer didn't waste any time or opportunities either. He regularly performed at closed government concerts in the Kremlin and on the NKVD club stage. It is said that on one occasion, he even earned praise from Stalin, who said,

‘You dance well. You jump very well!’

Thanks to his favorable relations with the authorities and a recently awarded Order of the Red Banner of Labor, Asaf managed to secure an audience with Lavrentiy Beria, the Deputy People's Commissar of Internal Affairs. However, it was Sulamif who went to the meeting with Beria, and this calculation turned out to be accurate. As a result of her plea, her sister was transferred with her son to Shymkent in Kazakhstan, replacing her labor camp sentence with exile.

This achievement was incredible, and for a long time, inmates at ALZHIR spoke of it as some kind of miracle. However, as it later turned out, this ‘miracle’ was entirely sanctioned and was part of a short-lived course to ease repressions following the removal of Yezhov and the ascendancy of Beria. The new commissar released several prisoners whose cases had not been concluded under his predecessor and granted the requests of dozens of relatives of ‘traitors to the motherland’, changing their status from prisoners to exiles.

Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov. Commissar of internal affairs of the USSR/RIA Novosti

To this day, Azari Plisetski remembers running to meet his aunt when she arrived in ALZHIR to help with their move to Shymkent and the paperwork. He heard the loud cries of women watching this scene. It seems certainly that at that moment, they were thinking about their own children and when they would be able to see them. He recalls:

My aunt hugged me, and I felt a strange crunch. It turned out that my entire jacket was stuffed with notes and letters that the unfortunate “Alzherians” had asked my mom to pass on to the outside world. Nothing could be carried out of the zone, and she simply sewed them into the lining of my jacket. Of course, she took an insane risk. But she couldn't refuse her friends in misfortune.

AN UNFORGIVABLE ABANDONMENT

The destiny of those children forcibly separated from their mothers and taken to orphanages unfolded dramatically. Even if mothers were allowed to take their children home after serving their camp terms, they often felt like complete strangers to each other as a vital emotional connection had often been lost. Unconsciously, the children couldn't forgive their parents for allowing them to become orphans and societal outcasts. After all, at the orphanages, they had been raised with a hatred for the ‘traitors to the motherland’. The belief that their loved ones were enemies of the beloved Stalin had been instilled in them. Some continued to live their entire lives convinced that their parents were the main culprits of their woes and misfortunes.

Mikhail Khrapkovsky. "Death to the vile traitors!" 1937/Wikimedia Commons

Saule, the younger sister of Rida Ryskulova, shares a memory of her sister:

They tore little Rida away from her mother at the age of three, like the other children, and sent her to the Osakarovka orphanage. When, upon her release, our mom came to take her daughter, she was met by a timid savage who could hardly speak, avoided people, and lacked the simplest everyday words in her vocabulary. She didn't possess basic social skills. Life as an orphan maimed her as it did me. Do I need to talk about the famine years in the orphanage, how I almost died from malaria and pneumonia, about the persistent eczema, about the eternal lice that not even the regular buzz cut could rid us of? I met my mother and sister in 1948. Can you ever compensate or resurrect a lost childhood spent without maternal care and love? For a long time, my sister and I couldn't even say the word “mother” and addressed her exclusively with the formal form of “you”. Watching our mother when we were out in public together or taking public transport was so difficult for us. She initially used to even stand in the tram, no matter how much we tried to get her to sit in an available seat. She was afraid, as a former prisoner, that she would be driven away and that she didn't deserve it. She confided in me, whispering that even in her dreams, she felt the invisible barrel of a rifle pressed against her back.

DAYS OF THE CITIZEN CHIEF

Over the fifteen years that ALZHIR was in operation (1938–53), the leadership of the camp changed three times. It was initially led by Alexander Bredikhin, and from 1 January 1939, Sergey Barinov became the chief of the Akmolinsk department. In 1940, the camp's leadership briefly passed to Mikhail Yuzipenko, but after the start of the Second World War, he was demoted to the position of Barinov's deputy, who again took charge of ALZHIR, the 17th Special Department of Karlag.

In photos from Barinov’s youth that still survive, we see a pleasant, open face, unruly curly hair, and a high, intelligent forehead. How did fate bring him to the steppes of Kazakhstan to become the overseer and jailer of several thousand women and innocent children? It is said that he was ‘exiled’ there for writing too audacious a letter to Stalin about excesses at the local level. However, this information is not definitively confirmed. According to various memoirs, Barinov was not a cruel man but rather a generous one. Inmates called him Valerian Valerianovich. He knew how, when necessary, to comfort, reassure, and find the right words. He was not devoid of sentimentality and good impulses. For instance, Maya Klyashtornaya recalled how Barinov would pick her up and pat her head, saying,

‘“You're my little swallow.” That's how I got the nickname Swallow.’

ALZHIR inmate Lydia Frenkel believed that, unlike many of his colleagues, Barinov understood perfectly whom he was dealing with and never believed in the guilt of the ‘traitors to the motherland.’ This became especially evident when Mikhail Yuzipenko, a known degenerate and sadist, briefly took over ALZHIR, and during this time, mortality among inmates reached record numbers. He was demoted, and Barinov was reinstated as chief. Of course, he had to maintain strict discipline, fulfill plans for agricultural crops, and produce military ammunition. It was under Barinov that the camp became a highly profitable, diversified enterprise, surpassing other Karlag divisions in its production metrics. These successes were achieved through hard labor and immense effort.

Sergey Barinov/From open access

The memories of Kazakhstan labor veteran Mariyam-Kazhi Nurzhanova, who lived in a neighboring village, have been preserved, and she unwittingly became a witness to a remarkable scene:

The exhausted camp inmates literally collapsed when teenagers emerged from the reeds and began pelting them with stones. The convoy guards laughed loudly, saying, “See, even here, in the village, they don't like you.” One of the prisoners named Gertrude stumbled and fell, hitting her face on these white stones. And then she realized that these stones smelled of cheese and milk. It was the national salted cottage cheese, dried in a special way. The woman picked up one of the “stones’, put it in her mouth—it turned out to be very tasty. Local residents sympathized with the unfortunate women, but, of course, couldn't express it. Fear gripped their souls. And yet, these white chunks of dried cheese speak more and much clearer about the true attitude of Kazakhs towards the ALZHIR prisoners than all the newspaper headlines cursing the “enemies of the people”.

Another noteworthy incident took place at the camp. In the 1960s and ’70s, Sergey Barinov, during his brief visits to Moscow, usually stayed with his former inmates, who would address him only as ‘Citizen Chief’. However, in 1990, during the wave of perestroika and various revelations, he was nearly declared a ‘Stalinist executioner’. The ALZHIR inmates collectively rallied to his defense and even wrote a joint letter in support of their Valerian Valerianovich. Barinov, who was already ill and old, managed to read it and, they say, shed a tear. He did not, however, live to see the opening of the memorial complex at the camp site in 2007.

LIFE AFTER DEATH

The Akmolinsk camp division officially existed until June 1953 and was dissolved by the order of the USSR Ministry of Justice. Several Karlag divisions were transferred to the Ministry of Agriculture and Procurements. Where the ALZHIR camp once was, the Akmolinsky Sovkhoz was established, and the settlement that had grown around the camp was named Malinovka. In the documentary film Traitors (1990, directed by Yevgeniya Golovnya), scenes depict the main character and former ALZHIR prisoner Ksenia Kazmina revisiting these places. The sight, it must be said, is rather gloomy. Typical five-story buildings now stand in place of the barracks. Some structures from her former camp life have survived, and Kazmina recognized them, as well as her former prison convoy escort, who stayed to live out his days here. No resentment or offense remains between the two. Everything has long passed and is done. They were now equal in rights, marked by advancing age and apparent poverty.

At the time the documentary was shot, there was no monument in memory of the victims and prisoners of ALZHIR on Malinovka’s central square, like the one depicting a cracked red star against the backdrop of prison bars and barbed wire that stands there now. A little later, by the ruling of the village assembly, a mound was erected, structures with the names of the deceased were installed, and a small museum was organized at the local cultural center.

However, Ksenia Kazmina did not witness any of these. The only thing she managed to see was a makeshift wooden cross lying directly on the dried grass—just one for all of those who were tortured, killed, and who perished. She had come here specifically to pay her respects.

Eighteen years later, in 2007, in Kazakhstan, where ALZHIR was located, 40 kilometers from the current Kazakh capital, Astana (formerly Akmolinsk), a large, already state-owned memorial and Museum of Victims of Political Repression and Totalitarianism was opened. In its own way, this is a grandiose project, encompassing the Arch of Grief, which symbolizes the entrance to sacred land, where the meeting of two worlds—the living and the dead—takes place. And memorial plaques, installed by the embassies of foreign states, in memory of the women of sixty-two nationalities who were prisoners in ALZHIR. The complex also contains the Tears monument, depicting a map of the Gulag network and the names of eleven camps located in the territory of Kazakhstan.

At the opening of the ALZHIR Memorial, the first president of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev, gave a passionate speech, saying, ‘Hitler killed others ... those with whom he waged war ... Our authorities killed our own people! Women and children were exiled to the bare steppe, condemned to hunger, diseases, torment, and death. The victims of political repression are not to be forgotten.’

The poignant verses of Sofia Solunova, written here in ALZHIR, behind the barbed wire, remind us why memory is so important:

‘The country does not believe us.

Not a single passerby sends us a reciprocal smile.

The country does not believe us!

What to do, my beloved! How do we prove to it that we are pure in heart!’

Multiple generations will dedicate their lives to analyzing all of these proofs. Thus, the Wall of Memory is such a significant monument, with the names of over 7,000 women who served time in the ALZHIR camp inscribed on black marble, arranged in alphabetical order with blinding density.

The museum itself resembles an adobe pyramid with a truncated top. We enter it through a tunnel, entering a space without windows. Light falls from above, creating a sense of a ghostly afterlife. In museum displays, the entire history of Kazakhstan is presented from the moment of joining the Russian Empire, and the tragic facts of the Soviet period—deportations, executions, entire nations of repressed people—are not ignored. More than 1.3 million people were deported to Kazakhstan; Germans, Turks, Koreans, Poles, Chechens, and Crimean Tatars were forcibly resettled. Against their will, these people ended up in Kazakhstan, yet those who stayed here consider this land their homeland.

On leaving the museum, we emerge from the semi-darkness of the building into the sun-drenched square, where the Arch of Grief rises in the center. In my memory, the sounds of the camp lullaby echo, a lullaby that Azari Plisetski sang to me in his pleasant baritone at his home in Moscow, on Tverskaya Street, picking out an unpretentious melody on the piano, taught to him by his mother:

Behind the bars, behind the locks

Days, like years, go by.

Children cry, even mothers,

Sometimes cry.

A new generation grows

With tempered hearts deemed greater.

My dear child, you must know

your father was never a traitor.