Few forms of animation in the world can rival Japanese anime in thematic diversity. From war, politics, and religion to economics, sports, love, sex, cuisine, art, horror, education, science fiction, superheroes, gambling, and humor, anime in Japan encompasses an astonishing range of subjects, offering something for everyone. And the viewer's age doesn't matter: you can grow up with anime and grow old with it.

- 1. How It All Began

- 2. And What About Miyazaki?

- 3. What Makes Anime Unique

- 4. The Connection Between Anime and Soviet Animation

- 5. All Ages Welcome: Choosing Anime for Your Life Stage

- 6. Kodomo Anime (for Children Between Six and Twelve)

- 7. Shōnen Anime (for Boys Between Twelve and Eighteen)

- 8. Shōjo Anime (for Girls Between Twelve and Eighteen)

- 9. Seinen Anime (for Men Between Eighteen and Forty-five)

- 10. Josei Anime (for Women Between Eighteen and Forty-five)

How It All Began

The history of Japanese animation dates back to 1917, with the release of three short animated films: Imokawa Mukuzo Genkanban no Maki (芋川椋三玄関番の巻, The Story of the Concierge Mukuzo Imokawa, 5 minutes) by Shimokawa Hekoten, Namakura Gatana (なまくら刀, The Dull Sword , 4 minutes) by Jun’ichi Kōuchi, and Saru-kani Gassen (猿蟹合戦, The Battle of the Monkey and the Crab, 5 minutes) by Seitarō Kitayama. Unfortunately, these works were almost entirely destroyed in the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923. The only surviving piece, The Dull Sword, was accidentally discovered in an Osaka antique shop in 2008.

Anime, in the modern sense, emerged only in 1963, when the American studio Hanna-Barbera's limited animation techniques and the term ‘animation’ (shortened to ‘anime’ in Japanese, as with many gairaigo* or loanwordsi

Astro Boy/IMDb

This first Japanese anime series was based on Osamu Tezuka's manga of the same name and addressed a deeply resonant issue for the Japanese people: the use of atomic weapons. After the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Tezuka aimed to show through the protagonist—Atom, a robot—that atomic energy could be used peacefully for the benefit of humanity. The first episode of Astro Boy begins with a tragic event—a car accident that claims the life of a young boy. To save his son, the father transforms him into a robot, thus creating Atom. The series concludes on a similarly dramatic note, with Atom sacrificing himself to save Earth. While targeted at children and teenagers, the show tackled complex themes, including death, and portrayed life’s harsh realities. Drama soon became a hallmark of anime, where often profound narratives lay beneath the surface of cute or comedic characters. Limited animation, incapable of achieving the smooth motion of full animation, pushed Japanese directors to focus on compelling storylines, character development, and emotional resonance.

Astro Boy/IMDb

The history of anime, it should be noted, is closely intertwined with manga comics. Manga introduced the principle of dividing audiences by gender and age into five main categories: kodomo (children), shōnen (boys), shōjo (girls), seinen (men), and josei (women). Popular anime series are often based on storylines from manga, and the process works less commonly in reverse, with manga being created based on an anime series. While manga is more often the source of original stories, it was anime that spearheaded the global spread of Japanese pop culture.

In Japan, the term anime primarily refers to terebi anime (テレビアニメ, television anime series), whereas the term animēshon eiga (アニメーション映画, animation) refers to feature-length or short animated films, often created using full animation techniques. Therefore, it is essential to distinguish between anime series and anime films. According to the philosopher Hiroki Azuma, by the 1970s, Japanese animation directors were divided into two camps:

1. Expressionists: Those who created animated films using full animation techniques, such as Ōtsuka Yasuo, Miyazaki Hayao, and Takahata Isao.

2. Narrativists: Those who focused on producing anime series using limited animation techniques, such as Rintarō, Yasuhiko Yoshikazu, and Tomino Yoshiyuki.

Azuma attributes the birth of anime's unique esthetic to the narrativist directors. They took American animation technologies, like limited animation, and adapted them to develop a distinct Japanese animation style.

And What About Miyazaki?

In this context, the works of Hayao Miyazaki are often mistakenly categorized as anime in the West. However, his animated films typically lack the characteristic archetypes or genre markers of anime (kodomo, shōjo, shōnen, seinen, josei). They instead align more closely with the tradition of auteur animation. One could even say that his films are genre-free family movies. Films such as My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Howl's Moving Castle (2004), Kiki's Delivery Service (1989), Ponyo (2008), The Wind Rises (2013), The Boy and the Heron (2023) and other masterpieces are designed for a broad audience, regardless of gender or age.

For example, Kiki's Delivery Service, about a young witch who travels to a new town with her cat to provide magical delivery services, could thematically fit within the mahō-shōjo (magical young girl anime) subgenre, which is discussed in greater detail in the shōjo anime section. However, despite the protagonist's magical abilities and her ‘magical companion’ (the cat), the film lacks key mahō-shōjo elements, such as henshin (変身, the metamorphosis of a girl into a magical being through a costume change), or a magical artifact (like a brooch, mirror, or pendant) and a magical phrase (for example, ムーン・プリズム・パワー・メイク・アップ, ‘Moon Prism Power, Makeup!’) that facilitates the transformation.

In Howl's Moving Castle, one can observe the archetype of the bishōnen (美少年), a beautiful young man. The mighty wizard Howl is depicted as a charming and attractive heartthrob, yet he is deeply lonely. While Miyazaki's films may borrow certain anime tropes (such as magical girls, bishōnen, or cute companion characters), they rarely adhere to these conventions entirely. Instead, they adapt these elements to the tradition of realism, exploring profound emotions and character introspection. In some cases, the characters are even stripped of their magical abilities to make their personalities more relatable and grounded in realism.

Kiki’s delivery service/IMDb

What Makes Anime Unique

When exploring anime series, many viewers may be struck by the distinctive esthetic used to depict characters' actions. This uniqueness can be understood through the concept proposed by Stevie Suan in his book The Anime Paradox: Patterns and Practices through the Prism of Traditional Japanese Theateri

The jo-ha-kyū concept consists of three critical components: jo (序, an introduction), ha (破, a turning point), and kyū (急, a rapid climax or resolution). This narrative structure or sequence of actions is employed not only in theater but also in tea ceremonies, martial arts, and other traditional practices. Each action begins slowly, builds to a pause, and then accelerates into a climactic conclusion. Moreover, in Noh theater, serious, tragic plays are often interspersed with comedic interludes from Kyōgen theater performed on the same stage. Similar patterns are evident in modern anime series, contributing to anime's unique esthetic, a seamless blend of dramatic and comedic elements.

Eboshi-ori (New Headquarters) by Tsukioka Kogyo (National Noh Theatre)/Wikipedia Commons

The vibrant visual style of anime also facilitates the quick communication of the characters' inner worlds. For instance, characters with fiery red or orange hair (such as Ichigo Kurosaki from the manga series Bleach or Kyojuro Rengoku from the series Demon Slayer) are often depicted with bold, explosive personalities. In contrast, characters with wheat-blond or silver hair (like Ginko from Mushishi or Takashi from Natsume's Book of Friends) tend to be reserved, shunning attention—often because of their ability to perceive supernatural entities.

Sailor Moon: Crystal (2014–2016), a reboot of the classic 1992 anime/IMDb

The distinct mukokuseki (無国籍, stateless) style of anime, a term coined by Iwabuchi Koichi, allows Japanese characters to easily pass off as Caucasian, enabling viewers from other countries to effortlessly identify with them. For example, Usagi Tsukino, the protagonist of the popular anime series Sailor Moon, is a Japanese schoolgirl with blue eyes and a cascade of blonde hair. Similarly, Naruto Uzumaki, the lead character of Naruto, appears as a blond, blue-eyed ninja trainee.

Many fans prefer watching anime with subtitles to fully appreciate the carefully selected voice acting performed by seiyū, or voice actors. It is a common tradition in anime for actresses specializing in ‘travesty roles’ to voice male characters. For instance, the young pirate Monkey D. Luffy from One Piece is voiced by Mayumi Tanaka, and the young ninja Naruto Uzumaki by Junko Takeuchi, among others. As a result, the audio in anime is just as significant as its visual artistry.

The Connection Between Anime and Soviet Animation

Japanese animators have often credited Soyuzmultfilm, the renowned Russian animation studio, and the Soviet school of animation as key influences. In the 1940s and 1950s, Soviet animation was more advanced than Japan's and offered a creative alternative to Disney's American productions. It is widely known that Lev Atamanov's The Snow Queen (1957) influenced Hayao Miyazaki’s work. However, fewer people are aware that the Soviet animated film The Little Humpbacked Horse (1947) inspired the legendary Osamu Tezuka to pursue animation.

According to Tezuka’s younger sister, he watched The Humpbacked Horse over fifty times, and it convinced him to abandon his medical career and focus on becoming an artist and animator. He even received his mother’s blessing to change professions after taking her to watch the film. A didactic message, the triumph of good over evil, a focus on the hero's emotional and moral qualities, and the tendency towards philosophical reflection and introspection strongly link Soviet and Japanese animation.

The Snow Queen (1957)/Soyuzmultfilm

All Ages Welcome: Choosing Anime for Your Life Stage

Anime caters to all demographics, offering categories like kodomo (for children), shōnen (for boys), shōjo (for girls), seinen (for men), and josei (for women). In the 2010s, Japan introduced a new category: comics and animation for the elderly. These stories often center on grandparents experiencing various adventures. One notable example is the 2017 anime series Inuyashiki, featuring Inuyashiki Ichirō, an elderly man overlooked by his family and disrespected by younger generations. A chance encounter with aliens transforms him into a cyborg, setting the stage for an unusual and moving tale.

Kodomo Anime (for Children Between Six and Twelve)

Anime originally began as entertainment for children, and kodomo anime remains a great starting point for those seeking wholesome, straightforward stories. The hallmark of these series is the kindness of their protagonists, while villains are never too frightening. For example, the long-running anime series Anpanman (1988–present) features characters based on baked goods. The titular hero is a superman-like figure with a head shaped like an anpan, a Japanese sweet bun filled with red-bean paste. His companions include Melonpanna, with a melon bun-shaped head; Currypanman, whose head resembles a curry-filled bun; and Shokupanman, whose head looks like a slice of white bread.

For a touch of nostalgia and heartwarming magic, viewers can watch the Unico films created by Osamu Tezuka in the 1980s. These animated tales about a magical unicorn offer a charming atmosphere of kindness and wonder. In addition, the kind-hearted robotic cat Doraemon, from the anime series of the same name (1973–present), travels from the future to help a struggling elementary school student, Nobita, overcome his challenges using a variety of futuristic gadgets from the twenty-second century.

Anpanman/IMDb

The most famous anime series for children, Pokémon (Pocket Monsters, 1997–present), falls under the sports genre and boasts a more dynamic plot than many others. The protagonist’s goal is to capture as many creatures (Pokémon) as possible to win battles. This anime is classified as spokon, a unique genre combining sports and perseverance (根性, konjō). The term itself merges the words ‘sports’ and ‘konjō’. The series subtly promotes sportsmanship to young audiences by featuring adorable creatures, especially the iconic yellow Pikachu.

Pokemon/IMDb

However, it’s important not to assume that anime with cute, youthful characters are always aimed at children, and viewers should always check the intended age rating. For instance, the anime series Made in Abyss (2017) features the young and innocent-looking protagonists Riko and the robot Reg, whose designs align with the kawaii esthetic (かわいい, adorable, tiny, charming). While the story begins cheerfully, as the characters descend into the abyss, they face terrifying bodily transformations in the best traditions of body horror. Consequently, Made in Abyss is categorized as seinen and targeted at male audiences aged eighteen and older.

Made in the Abyss/IMDb

Shōnen Anime (for Boys Between Twelve and Eighteen)

The most popular anime genre is aimed at young male audiences, featuring thrilling adventure stories centered around the themes of friendship, effort, and victory. The protagonists are typically teenage boys navigating the challenges of growing up and self-discovery. The plots often revolve around camaraderie and rivalry between male characters, and the story is focused on the pursuit of a goal achieved through overcoming numerous obstacles. While hints of romance appear, female characters usually play secondary roles or serve as ‘battle companions’.

Frequently, the antagonist harbors a dark side they must confront and overcome. This dark power is often tied to ancient Japanese folklore, including legends about shape-shifting animals like the nine-tailed fox, yūrei (ghosts), and yōkai (mystical creatures).

Global recognition for shōnen anime began in the early 2000s with the release of iconic series like One Piece (1999–present), Naruto (2002–2007), and Bleach (2004–2012). These series center on young men striving to become the strongest and most powerful in their chosen fields. Today, these legendary shōnen anime are collectively known as the ‘Big Three’.

The unique thematic ‘mecha’ genre (short for the English word ‘mechanism’) emerged for a teenage audience, featuring an anime series about giant robots piloted by humans. The first fully realized robot character appeared in Osamu Tezuka’s manga and anime Astro Boy. Initially, robots were controlled from a distance, such as with a remote control, as depicted in the anime Tetsujin 28-go (1963–1966).

A shift toward a more realistic interpretation of the mecha genre came with the anime series Mobile Suit Gundam (1979), where giant robots were no longer portrayed as sentient beings but as advanced battle suits and the pinnacle of technology. Finally, Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995–1996) introduced a new perspective, presenting giant robots as integrated entities connected to their pilots. In this series, the pilots physically feel the pain and damage inflicted on the robots. Notably, the pilots are not seasoned adults but teenagers grappling with depression and personal struggles.

The Mecha Genre

The mecha genre never exists in a ‘pure’ form; it is always combined with other genres like comedy, adventure, or action. A fascinating example of such a blend is the spirited anime series Gurren Lagann (2007), set in a unique universe centered around the concept of spiral energy. This series presents the mecha genre with a comedic twist.

Gurren Lagann/IMDb

Shōjo Anime (for Girls Between Twelve and Eighteen)

In the mid-1960s, alongside shōnen anime for boys, the shōjo anime genre for girls also began to emerge. These stories typically feature a teenage girl protagonist navigating life’s challenges and striving to form romantic relationships. Similar to shōnen anime, shōjo protagonists also face various obstacles, drawing inspiration from the tradition of shōjo shōsetsu, which are educational novels about a young heroine overcoming life’s difficulties. An example is the anime series Candy Candy (1976–1979), which follows Candy, a girl from an orphanage, overcoming numerous trials thanks to her cheerful and resilient personality.

Candy Candy/IMDb

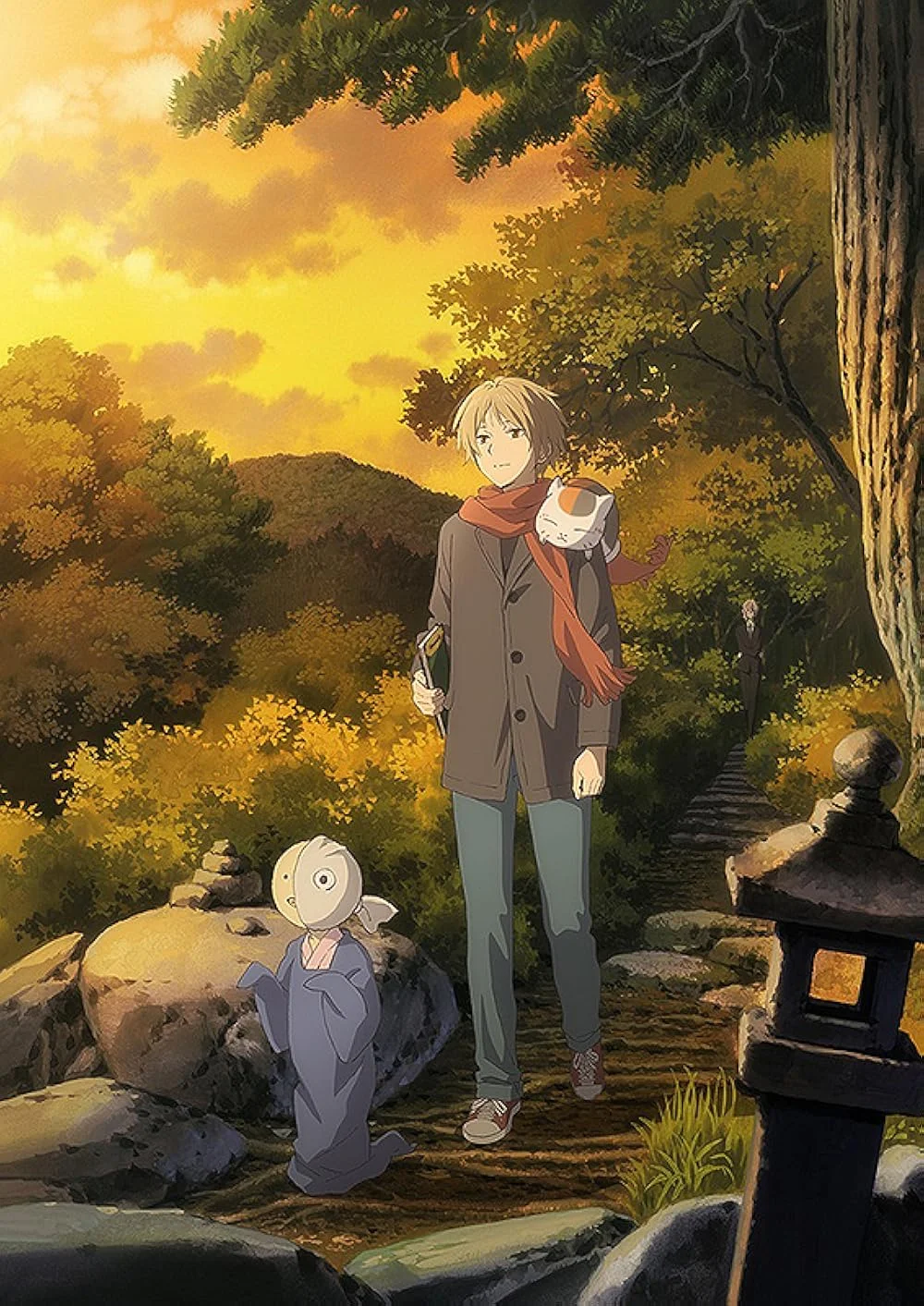

Occasionally, the main character in shōjo anime can also be male. This first occurred in Hideko Mizuno’s manga Fire! (1969–1971), which told the story of an American teenager with a troubled past, including jail time, who dreamed of becoming a musician. Among modern shōjo anime featuring male protagonists, Natsume’s Book of Friends (2008, 2009, 2011, 2012) stands out. It focuses on Natsume Takashi, a Japanese high school student with the extraordinary ability to see spirits and supernatural beings. The anime is noted for its lyrical tone and lack of violent battles, catering to the preferences of a female audience.

Natsume's Book of Friends/IMDb

The Magical Girl Genre

A key thematic subgenre for the female audience is magical girl anime ( 魔法少女, maho shōjo), focusing on magic and sorcery. The genre originated with series like Sally the Witch (1966–1968) and Secret of Akko-chan (1969–1970). Sally the Witch follows a sorceress from a magical realm who uses her powers to fight evil after arriving in the human world. Akko-chan is a young girl who acquires a magical mirror that allows her to transform into anything she wishes. In Bewitched Meg (1974–1975), a young sorceress is sent to Earth to learn about ordinary human life as a prerequisite for becoming the next queen of the magical kingdom. Overcoming monsters and rival witches, Meg evolves from a selfish girl into a generous and loving young woman.

Akko's Secret/IMDb

In the maho shōjo genre, the protagonists are often depicted as emissaries from other worlds. This structure mirrors the classical Japanese folktale Taketori Monogatari (The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter), where the extraordinary girl Kaguya-hime is revealed to be a princess of the Moon Kingdom.

The most iconic example of the maho shōjo genre is the anime series Sailor Moon (1992–1997), which masterfully blends elements of magic and superheroes. In this story, a team of sailor-suited warriors battle enemies. In their daily lives, these girls act like typical Japanese schoolgirls, but in moments of danger, they transform (henshin) into defenders of the Moon Kingdom, embodying the classic superhero motif of the alter ego. Sailor Moon achieved immense popularity internationally, gathering a devoted global fanbase. For instance, in Russia, passionate fans of the series were affectionately called munyashki, from the English word ‘moon’.

Sailor Moon/IMDb

Maho shōjo anime often features a variety of cute creatures—animals, animated plush toys, or fantastical beings. These ‘magical helpers’, a term from Vladimir Propp'si

Maho shōjo anime also emphasizes the attractiveness of male characters, often portraying them with large, girl-like eyes, while the heroines themselves may have rather ordinary appearances. The color palette in shōjo anime typically features soft or pinkish hues, adding to the genre's distinctive charm.

Maid Sama!/IMDb

In this type of anime, an intriguing character archetype that viewers often encounter is known as ‘the girl in men's clothing’ (男装の少女, dansou no shoujo) or ‘warrior girl’. This archetype was originally created by Osamu Tezuka in the manga Ribon no Kishi, (Princess Knight, 1953)i

In the 1970s, the feminist and manga author Riyoko Ikeda expanded upon this archetype by creating the character of Lady Oscar, the protagonist of the manga and anime The Rose of Versailles (1979–1980). According to the plot, Lady Oscar was raised as a boy, rose to the rank of captain of the palace guard, and protected Queen Marie Antoinette during the French Revolution. Over time, the ‘girl in men's clothing’ archetype began to fade, replaced by male characters with feminized traits, a concept that migrated to the josei genre—anime and manga for women—particularly in the boys' love subgenre.

Kamisama kiss!/IMDb

Seinen Anime (for Men Between Eighteen and Forty-five)

The seinen anime genre emerged in the 1970s, marked by the release of the first season of the anime series Lupin III Part 1 (1971–1972), which centered on the grandson of the legendary gentleman thief Arsène Lupin. This series included risqué jokes and nudity, distinguishing it as a product for mature audiences. Essentially, seinen anime encompasses the same thematic genres as shonen anime—mecha, sports, adventure, action, science fiction, space opera, comedy, superheroes, and more—but with deeper thematic explorations and more sophisticated visual effects.

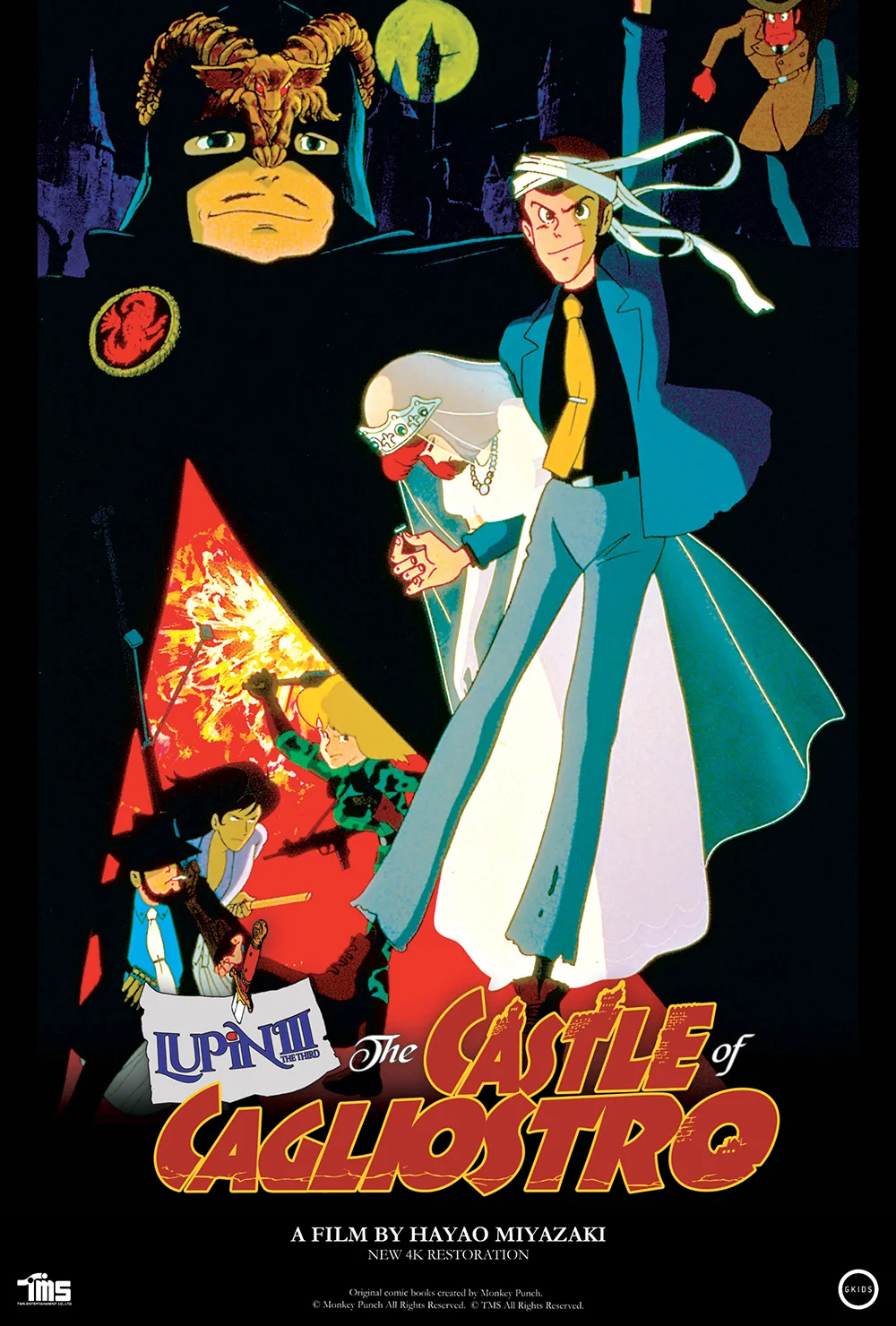

A story's age rating can sometimes be adjusted, moving it to a different audience category. For example, Hayao Miyazaki adapted the Lupin III storyline for a younger audience with the anime film Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro (1979) after the anime's first season failed to find success with adults.

Lupen III/IMDb

The influence of early seinen anime can be seen in the iconic series Cowboy Bebop (1998–1999), directed by Shinichiro Watanabe. The series’ protagonists, Spike Spiegel and Jet Black, bear a visual resemblance to Lupin III and his accomplice Jigen. Cowboy Bebop is also intended for adult audiences and is especially appealing to fans of jazz, action, and poignant love stories.

Cowboy Bebop/IMDb

The seinen anime genre is generally characterized by more intense themes such as career development, deep philosophical reflections on global issues, self-exploration, and depictions of sex or brutal violence. The style of seinen anime tends to be more rugged, harsh, and dark, leaning toward realism and detailed artwork. Large eyes are rarely seen unless the story involves children or charming female characters. The color palette of the art is typically darker or more muted compared to shonen anime.

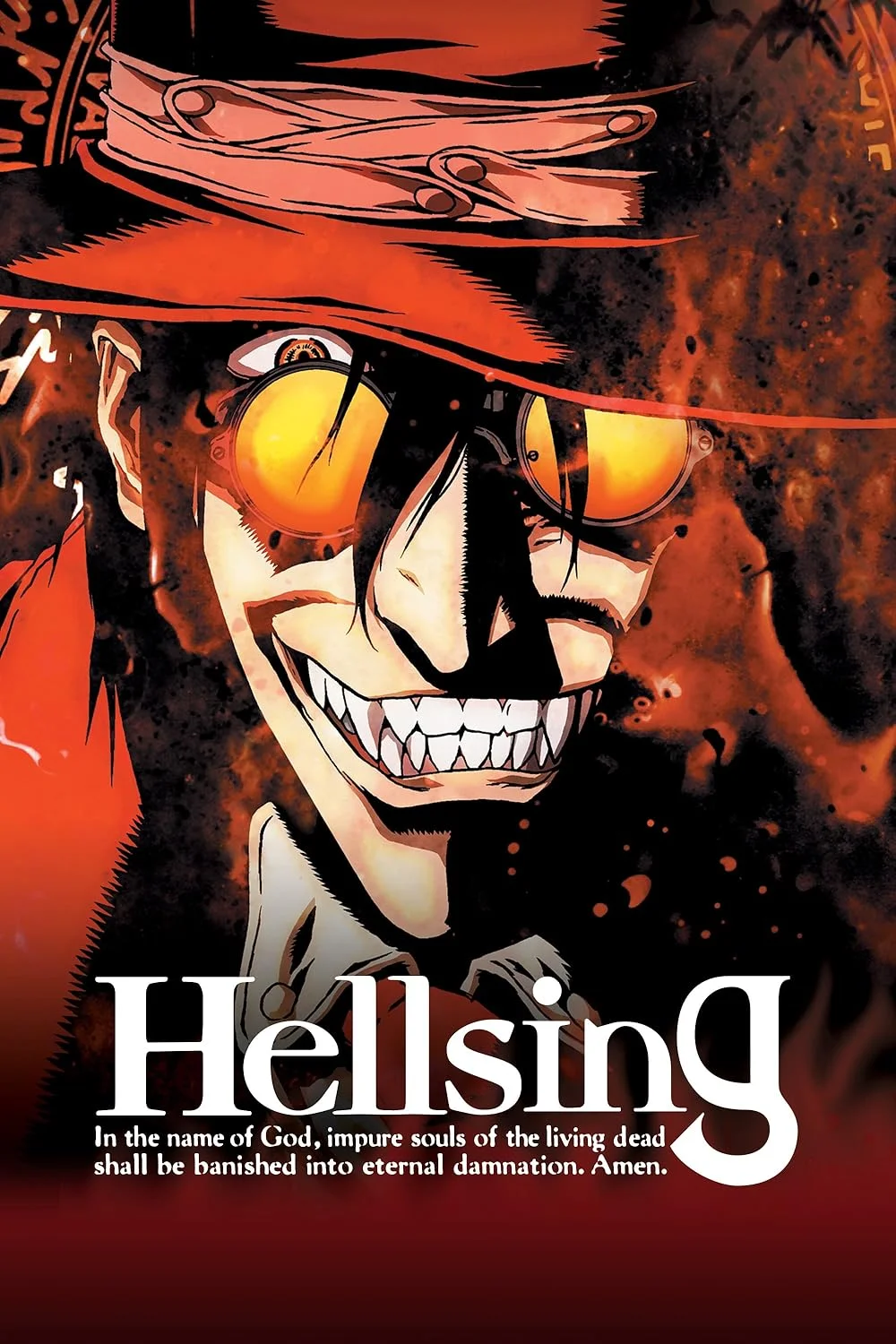

Some of the most notable seinen anime include Berserk (1997–1998), a dark historical fantasy with intense battle scenes and elements of explicit eroticism; Hellsing (2001–2002), a supernatural action series about battling the undead that continues the themes of Bram Stoker’s Dracula; and One Punch Man (2015), a parody of superhero stories where a bald protagonist defeats his enemies with a single punch.

Hellsing/IMDb

The seinen category is closely tied to the recognition of Japanese animation in the West. The anime film Akira (1988), based on Katsuhiro Otomo's manga of the same name, explored themes such as violence and corruption. Delinquent teens, secret experiments, and biker gangs in anime stood in stark contrast to Western animation of the late 1980s, especially Disney films, which were primarily targeted at children.

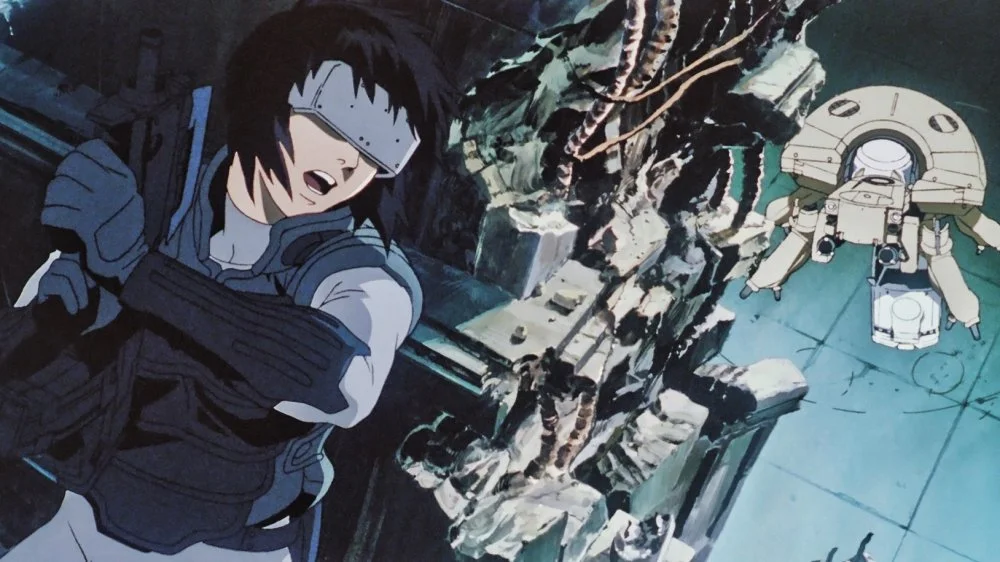

Another seinen anime film celebrated in the West is Ghost in the Shell (1995), which delves into the concept of artificial intelligence. The protagonist, police major Motoko Kusanagi, spends much of the film contemplating her identity and the meaning of being human.

Ghost in shell/IMDb

However, seinen anime is not exclusively tied to grim male-dominated worlds, apocalyptic themes, or dark fantasy. Some seinen series are created by female authors, bringing a lyrical atmosphere and focusing on everyday life or the supernatural. For instance, the anime series Mushishi (2005–2006, 2014) tells the story of the wandering healer Ginko, who has the ability to interact with mysterious creatures called mushi. Meanwhile, the anime series Chi’s Sweet Home (2008, 2009, 2016) is a touching tale about the Yamada family adopting a stray kitten.

Josei Anime (for Women Between Eighteen and Forty-five)

The youngest in the anime landscape, josei anime, emerged in the 1990s. It explores themes of relationships with greater depth and seriousness, addressing topics such as pregnancy, motherhood, women's physiology, marriage, and self-actualization. Unlike traditional depictions, some josei heroines do not rely on the support of a strong male figure but are capable of solving pressing issues themselves or holding leadership positions at work.

Say i love you/IMDb

One of the earliest examples of josei anime is the short film Cream Lemon: Escalation (1990, original video animation (OVA)), which tells the story of Hiromi, a twenty-year-old office lady working at a large Japanese company. Her duties involve serving tea and running minor errands. One evening after work, two suspicious men force her into a car and take her to a love hotel, where the managing director offers her the position of the manager of the establishment.

Josei anime can incorporate various elements, such as horror in Pet Shop of Horrors (1999, OVA), where the mysterious owner of a peculiar pet store sells exotic but dangerous creatures to people. Another example is the romantic comedy Princess Jellyfish (2010), based on the manga by Akiko Higashimura. The story follows Tsukimi, an eighteen-year-old jellyfish enthusiast living in a women-only dormitory, whose life takes a turn when a young man disguised as a woman enters their world. Tsukimi, meanwhile, strives to establish herself as an illustrator.

Unlike shōjo anime, josei anime works rarely delve into mysticism or magic, instead focusing on everyday life and realism.

Princess Jellyfish/IMDb

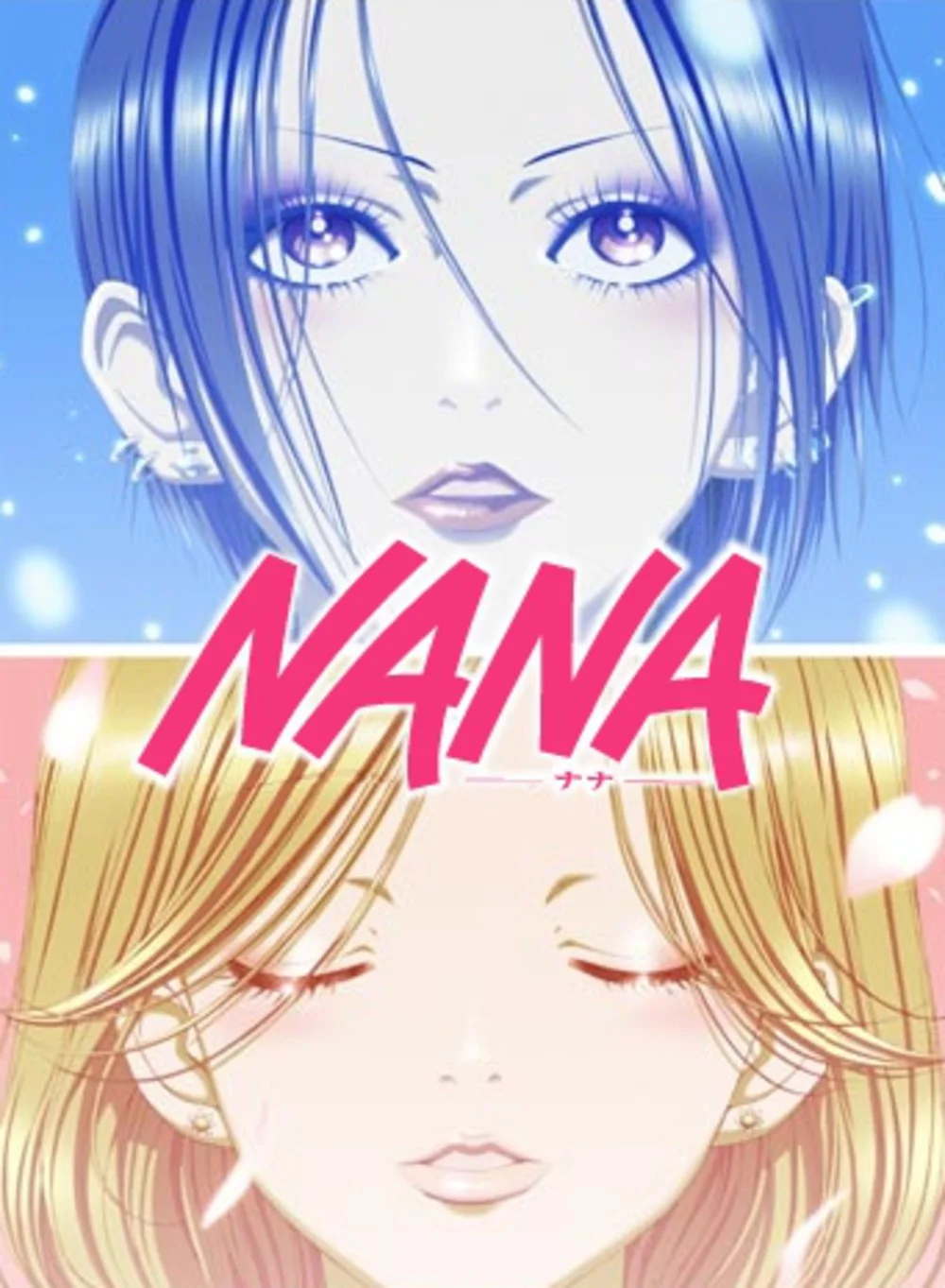

From this perspective, the anime series Nana (2006–2007), based on the manga by Ai Yazawa, is particularly intriguing as it explores two contrasting paths of two women's lives. The story follows two protagonists with the same name, Nana, who move to Tokyo and end up as roommates. Nana Osaki dreams of fulfilling her lifelong goal of becoming a professional singer. In contrast, Nana Komatsu does not aspire to a career but rather longs to find true love. She works a simple job at a publishing house, performing tasks like brewing tea, cleaning, and copying documents. After becoming pregnant by the leader of a popular band, Nana Komatsu adopts the life of a homemaker, finding her purpose in caring for her loved ones and creating a warm home environment.

Nana/IMDb

Nana Osaki, on the other hand, has a boyfriend who wishes to start a family, but she is uninterested in raising children. She believes that a potential pregnancy could jeopardize her career as a singer and takes contraception very seriously. Ultimately, Nana Osaki struggles to find personal happiness and near the end of the series, she learns that her lover has been in a car accident. The relationships depicted in Nana lack the clarity often seen in the shōjo genre, with outcomes that may include breakups or divorces, reflecting more realistic behavior.

Josei anime is also connected to the boys' love genre, which focuses on romantic and sexual relationships between male characters. This genre serves as a space for women’s erotic fantasies, often encoding a female character into the more feminine and passive male role. It is believed that women use this medium to move away from traditional gender roles and showcase relationships based on equality.

Classmate/IMDb