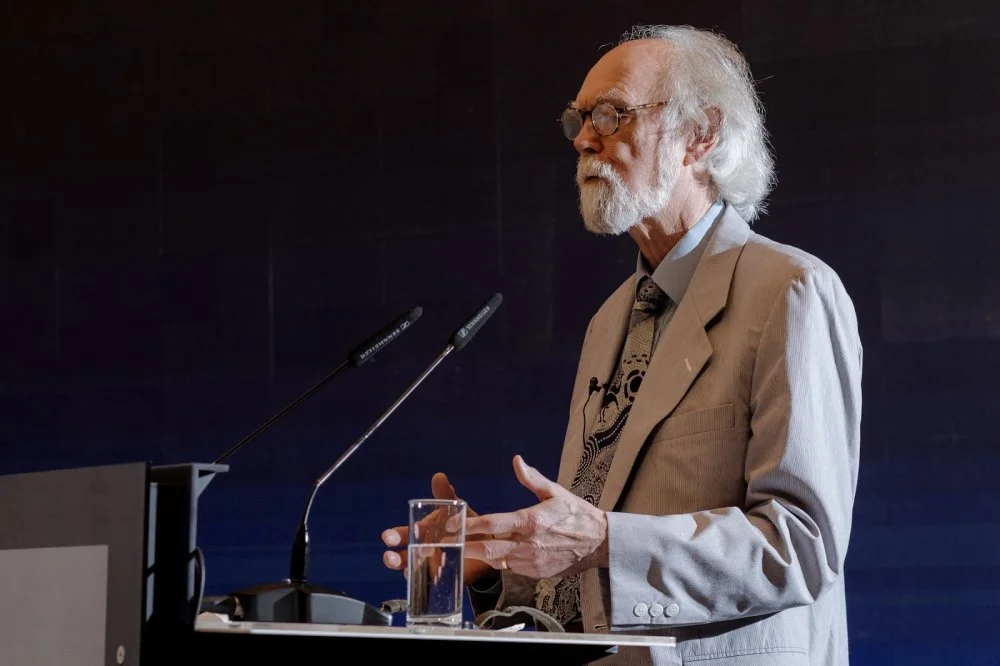

As the trade war launched by US President Donald Trump against China—and even some of his own Western allies—plunges the world into tariff chaos and sparks geopolitical tensions, we revisit the key insights from a lecture delivered by Professor Barry Buzan, a leading international relations theorist and Emeritus Professor at the London School of Economics. Speaking at the Qalam Club in September 2024, Buzan explained why the era of Western dominance is drawing to a close, what kind of world order is emerging in its place, and what the transition to a more pluralistic—and far less predictable—system really means.

How the Western World Order Emerged

Barry Buzan / Qalam

Over the last couple of centuries, the Western world order arose and was shaped by the first round of modernization, which began around the 1840s. During this period, several Western countries—and Japan—underwent rapid industrialization, thereby giving themselves an enormous edge in terms of wealth and power, far beyond anything that had existed in history. This created a world structured around a very small group of core countries—hardly more than a dozen—and a vast periphery consisting of everyone else.

These countries shaped the world order according to its own interests, often unconsciously—and they could do so because of their massive advantage in material resources. This translated into cultural and political authority. From the mid-nineteenth century, countries like China were confronted with a difficult question: Did modernization equal westernization? Indeed, at the time, it seemed that to modernize, one had to abandon one’s own culture.

Yōshū Chikanobu. Ballroom dancing at the Rokumeikan. Tokyo. February 8, 1888 / Wikimedia Commons

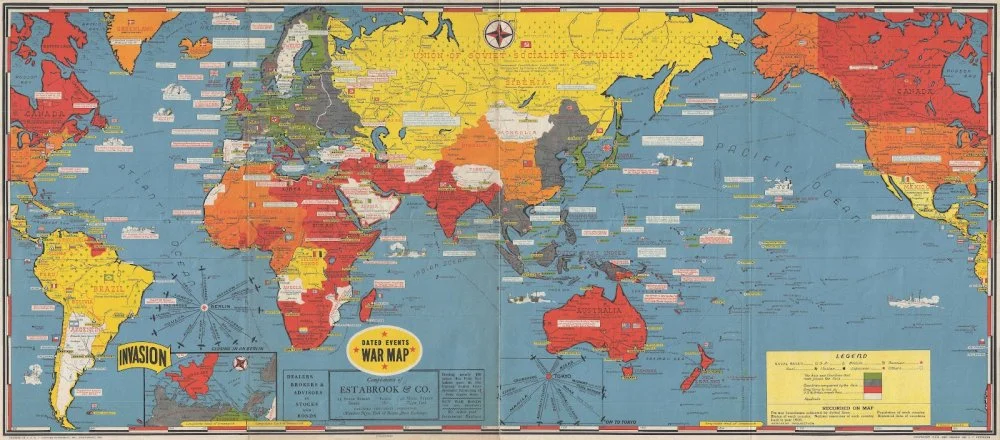

The degree of dominance of this small core over the large periphery is demonstrated by the fact that, throughout the period of the Western world order, the Western powers were fighting amongst themselves, sometimes in very significant ways, such as during the First and Second World Wars. And even when they were in conflict with one another, it was still relatively easy for them to maintain control over the rest of the world and to dominate the global order.

The first phase of this Western world order was colonial—in other words, it involved direct occupation. For the purposes of this analysis, I include Russia—not exactly as part of the West, but certainly as part of Europe and as a participant in the broader Western project of domination. Like the other European powers, the Russians built themselves a big empire because they were stronger, and those around them were weaker.

Stanley Francis Turner. World map showing events of World War II. 1944 / Geographicus

This colonial phase of the Western world order lasted until 1945. After that, it evolved into something a bit more gentle, less brutal and blunt, or what I would simply call the ‘Western global order’. Although former colonies regained sovereignty, they remained economically, and to an extent militarily and politically, subordinate.

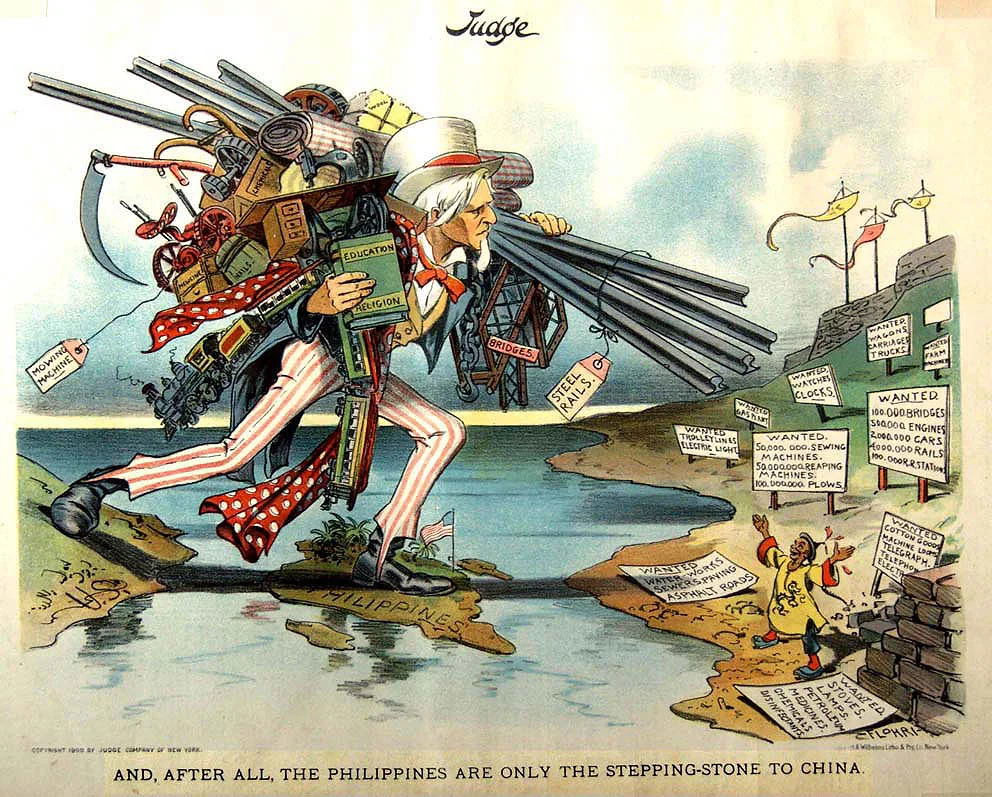

The Western world order was characterized by a ruthless pursuit of development, often rapacious in nature. The Western powers set the model for becoming as wealthy and as powerful as possible, as quickly as possible, with little regard for the environmental, social, or ethical consequences of their actions.

Coffins of French soldiers in the port of Casablanca before repatriation. Raymond Lavagne (presumed). 1913 / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Another feature of this order was the creation of an intense global economy. From the 1840s onward, the West built a powerful global trading and financial system that drew everyone into its orbit—whether they wanted to be part of it or not. This system shaped the nature of colonialism: ports, railways, and other infrastructure were constructed primarily to extract resources from the colonies and feed them into the industrial core.

Despite building a global economy, the West never figured out how to structure and manage it properly. We’ve seen several major cycles of economic governance: free trade and the gold standard in the nineteenth century, economic nationalism during the interwar period, and the Bretton Woods system after 1945, which attempted a compromise, aiming to create a global trading system with restrictions on financial flows. It lasted until the 1970s, when it too broke down because it created big problems for the United States.

Opening of the first railway in China from Shanghai to Woosung Port. 1876 / Illustrated London News / Wikimedia Commons

So, if the 1840s marked the beginning of the Western world order, the 1970s might well be seen as the start of its decline. Guerrilla wars and limited nuclear proliferation made it difficult to occupy territories. More importantly, a second round of modernization began in East Asia—with the Four Asian Tigers (South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore), followed by China and India.

And that's what’s driving deep pluralism: development outside the West. From the 1840s to the 1970s, almost no country of consequence modernized apart from the original core. But since the 1970s, more and more have done so.

Singapore, North Bridge Road. Circa 1972 / Alamy

Understanding Deep Pluralism

Deep pluralism is not just a power shift between the US and China. That is only one aspect of the change but not the most important part. The key development is that we are witnessing a significant transformation: a long-standing small core of industrialized, modernized powers is now expanding. Countries like China and India are moving into that core, which means it is no longer Western-dominated. This is a global transition of power.

Another important point is that this transition is not about the fall of the West. We are not talking about a collapse akin to that of the Roman Empire. The West is not going away, but what remains to be seen is how it will be structured in the future—whether it will stay a unified bloc or split into European and American components. That’s still an open question.

A pair of Class CT270 Pacific of Taiwan Government Railways at Chia Yi depot. October 4, 1974 / Photo by Rail Photo / Construction Photography / Avalon / Getty Images

What is clear, however, is that we are moving into a system with multiple centers of wealth, power, cultural influence, and political authority. The West will remain one of those centers—wealthy and powerful—but not dominant in the extraordinary way it has been for the past couple of centuries.

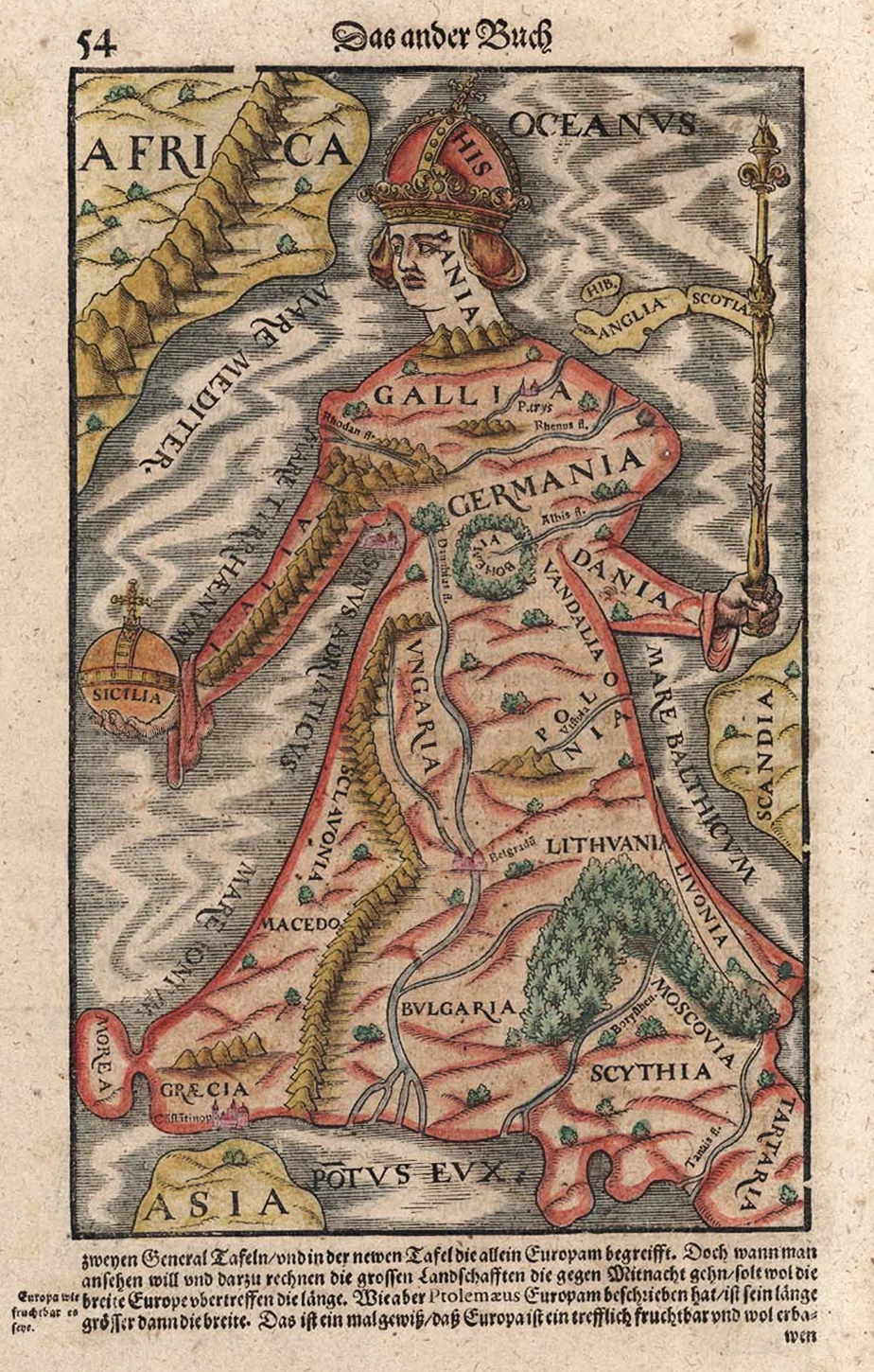

In a sense, we’re reverting to a more ‘normal’ pattern of global relations—one that existed before modernization, when different civilizations were relatively equal in wealth, power, and authority. The difference now is that they are tightly integrated on what is effectively a much smaller planet.

Let’s look at a few of the key features of this emerging world order as well as some of its risks and opportunities.

Sebastian Munster. Map of Europe as a queen. 1570. Basel / Big Think / Wikimedia Commons

One major issue is that we still haven’t figured out how to manage the global economy. The challenge is finding the right balance between economic nationalism on the one hand and the global market on the other. We've tried both extremes, and neither has worked. We’ve tried the middle path, and that didn’t work either. Then came the neoliberal experiment up until 2008, which also failed. Where are we now? The truth is that we don't really know. Economic nationalism is on the rise; the global market is in trouble.

So, we’re in the midst of a fifth attempt to figure out how to run a global economy. It's clear that we need a global system, but we also need a degree of national economic autonomy to maintain political stability and sovereignty. That dialectic is as yet unresolved and will remain so for the future.

In current public discourse, there’s a lot of talk about polarity, about a return to bipolarity, with China and the US, or multipolarity, with Russia, the EU, India, and others. To some extent, that’s true. Power and wealth are now more widely distributed, but the significance of that distribution is changing a lot.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Photo by Raghu Rai. Circa 1980s. London / The India Today Group / Getty Images

For the past two centuries, debates over bipolar or multipolar systems have assumed that the major powers—however many—were competing to dominate the world. That’s a fair description of global politics from the nineteenth century through the Second World War and the Cold War, where the assumption was fundamentally one of power politics. Today, that assumption no longer holds. Bipolarity or multipolarity now means something different, and the current problem is not about who will dominate the system, but that no one wants to run it at all.

Western powers have lost the appetite for global leadership, and their authority—particularly that of the United States—is no longer widely respected. Meanwhile, the emerging powers—China, India, and possibly Brazil—are not eager to assume responsibility either. They claim to be developing countries, lacking the resources or capabilities to manage global affairs. They want the status of great powers, but not the responsibilities.

We are entering a strange world that has many great powers in it, none of whom want to take responsibility for maintaining global order. Given the toll that managing world order took on the United States, that reluctance is understandable, but it is nonetheless a serious problem.

Citizens celebrating India's independence from British rule in the streets of Calcutta / Keystone / Getty Images

We live in a world faced with collective challenges, climate change foremost among them, which demand urgent collective action. But so does the management of the global economy, and so do pandemics and other transnational crises.

Whether the system is bipolar or multipolar is no longer the central issue. The real problem is that no power, or a combination of powers, is willing to step up and manage the world responsibly. This emerging world order, defined by deep pluralism, will be strongly anti-hegemonic. There is no consensus anywhere for a single leader. The West’s long history of dominance, fueled by colonialism and decades of intervention, has fostered widespread resentment, which now manifests as a general resistance to hegemony itself.

That resistance would extend to any new power trying to assert global leadership. China is not going to step into America’s shoes because it wouldn’t be granted the legitimacy to do so. Nobody wants the world to be run in that way. It is going to be run collectively or not at all, and that is the nature of the political problem emerging in front of us.

A particularly dangerous scenario would be if Russia, China, and the Global South aligned against the West, creating a deep divide that would make global cooperation nearly impossible. That, in my view, would be the worst possible outcome.

Beijing. Photo by Bao Jianping. February 25, 2025 / Getty Images

One of the key legacies the West has given the world—not imposed, but certainly disseminated—is a ruthless, unrestrained drive for development. Both the currently leading economies and those striving to catch up are focused on becoming rich and powerful as quickly as possible and by any means necessary. This relentless pursuit is now a major collective problem as we are approaching the planet’s carrying capacity.

Emil Flohri. «And, after all, the Philippines are only the stepping-stone to China», Judge Magazine, April 21, 1900 / Wikimedia Commons.

If this continues, the conditions that have sustained civilization for the past five or six thousand years could shift dramatically, engendering changes that are hard to predict, but likely to undermine the foundations of our societies.

Anti-Trump protesters in Trafalgar Square. Photo by Alisdare Hickson. January 20, 2017. London, United Kingdom / Wikimedia Commons

The Return of ‘Civilizations’

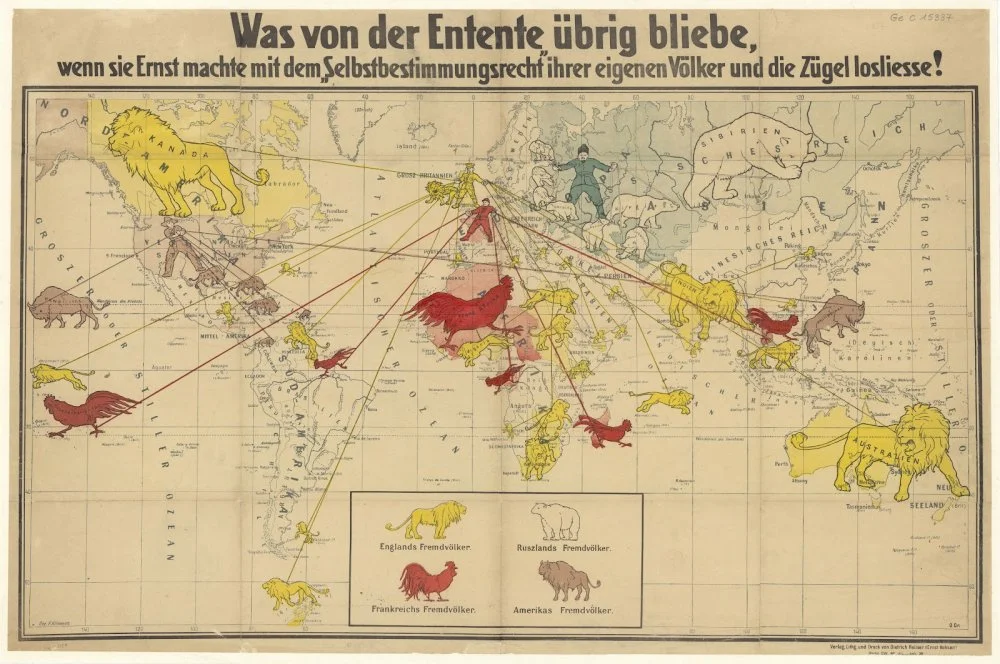

Interestingly, the concept of ‘civilization’ itself is undergoing a transformation in global discourse. China is at the forefront of this revival, and for good reason too: it benefits from civilizational framing. India, with its Hindutva narrative, and parts of the Islamic world, including Iran, are also adopting civilizational identities. Even the European Union is comfortable defining itself in these terms.

Whether this applies to the US remains unclear. Russia, too, faces challenges in constructing a coherent civilizational identity. Its national narrative has long oscillated between Westernizers and Slavophiles. At present, the Slavophiles dominate, framing Russia as a central Eurasian civilization. But whether Russia is truly a distinct civilization or part of European civilization remains unresolved—both within Russia and internationally. Like Japan, Russia occupies an ambiguous position in relation to Europe and the West.

Dietrich Reimer Verlag. Satirical map «What would remain of the Entente if it truly respected the right of its peoples to self-determination and let go of the reins». 1912 / Bibliothèque nationale de France

There are several risks associated with the deep pluralist system we are entering. One of the most significant is the unwillingness of both old and new great powers to manage the international order. The established powers are weary, their electorates reluctant to bear the burdens of global leadership, and their international legitimacy eroded. The rising powers, in turn, claim they are still developing and not equipped to take on such responsibility.

This points to a clear prediction: over the coming decades, there will be a prolonged contest over the structure of international institutions. Bodies such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization are losing legitimacy, as they are seen, accurately, as Western constructs serving Western interests. Reforming them is nearly impossible; for instance, restructuring the UN Security Council is blocked by the mutual veto powers of its permanent members. The BRICS nations are already building alternative institutions, some as bargaining tools, others as genuine alternatives. It is clear that this is going to be a long contest.

Map of BRICS members and prospective members / Wikimedia Commons

All of this unfolds in the absence of any coherent replacement for the liberal vision of world order. Like it or not, the West did offer a universalizing, albeit often threatening, vision with principles and structure. Now, liberalism itself is in crisis, and no other major power has proposed a credible alternative. Russia, China, and India may all oppose the liberal order, but none of them have articulated a constructive, coherent global vision. They know what they reject, but not what to build in its place. Questions about who will manage global affairs and how cooperation can be structured are unavoidable but currently go unanswered.

There is also the looming risk of neo-imperialism. Many observers already view Russia through this lens, and some harbor similar concerns about China. While the West seems to have learned the lessons of its imperial past and is unlikely to revert, it’s not clear that others share this restraint. As wealth and power diffuse, imperial tendencies may re-emerge in some regions.

Henri Meyer. French political cartoon - «Foreign powers carving up China». Le Petit Journal. 1898 / Wikimedia Commons

The Likelihood of Another World War

There is always a small risk of a world war, though I’m not someone who loses much sleep over that possibility. I believe that nuclear weapons, and the fear of nuclear conflict, do a fairly effective job of preventing it.

However, beneath that threshold, there is considerable room for serious conflict as we are already seeing in Ukraine and elsewhere. A particularly worrying trend is the rise of actions that wouldn’t traditionally be classified as war. I’m talking about cyberattacks and infrastructural warfare—sabotaging pipelines, cutting underwater cables, and attacking shipping lanes. These attacks on social and critical infrastructure are becoming more frequent, whether through the internet or via physical means. What’s especially troubling is that this kind of warfare is still poorly understood. There are no clear mechanisms for escalation control or for preventing these incidents from spiraling into larger conflicts.

Exxon gas station following the cyberattack on Colonial Pipeline. On May 7, 2021, the attack disrupted the largest pipeline system in the U.S. for five days, leading President Joe Biden to declare a state of emergency. Photo by Dustin Chambers. May 13, 2021 / The Washington Post / Getty Images

To avoid global breakdowns, we must stabilize the economy and address climate change. If we fail, we will face a very different—and much less hospitable—world. Imagine, for instance, a future in which the world’s major coastal cities are underwater due to a two- or three-meter rise in sea levels. That’s not science fiction—it’s a real, foreseeable transformation.

Yet this moment also contains opportunities.

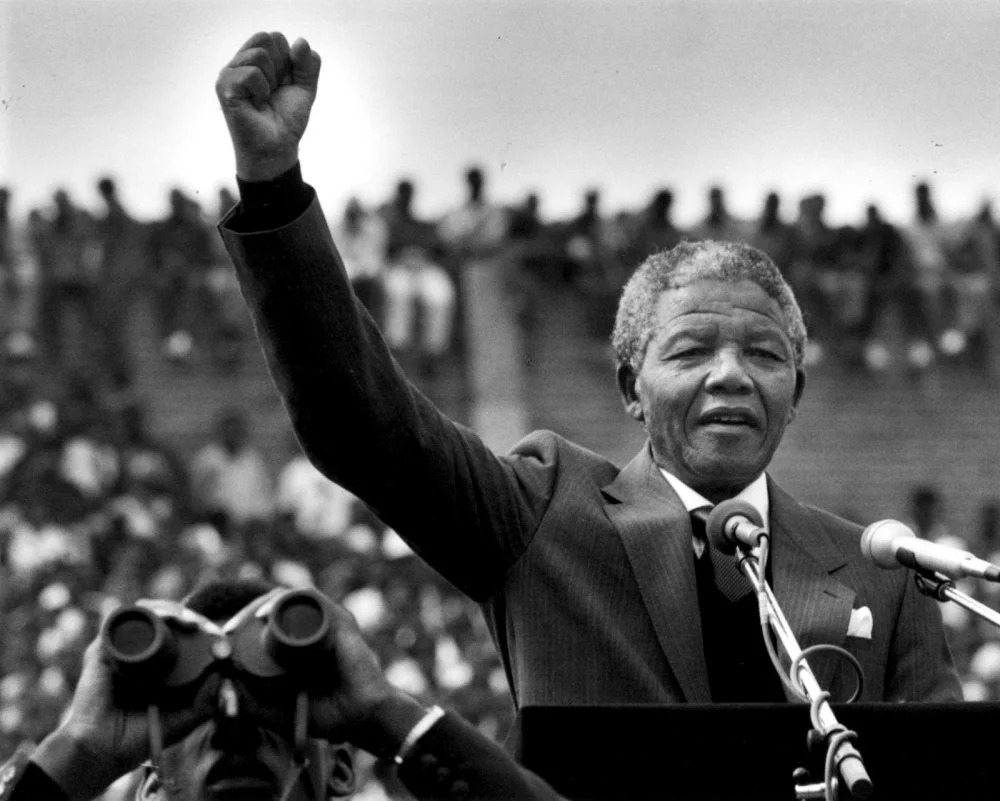

First, the revival of civilizational identity can offer a new foundation for global equality. Much like racial equality has become a widely accepted value, civilizational respect could help diverse powers cooperate. This would run counter to the liberal, homogenizing vision of global order. Instead, it would demand a world system in which differences are not only tolerated but valued.

Nelson Mandela in Soweto two days after his release from prison in Cape Town. Photo by Joanne Rathe / Documenting South Africa Archives / The Boston Globe / Getty Images

Second, sustainable development offers another path forward. The global energy transition is underway, but we also need to rethink development itself, especially environmental cost accounting. This applies to both leading economies and those catching up. Everyone wants to develop further, but we must rethink how we do it—and agree on some shared standards. Finally, we must remake global institutions to reflect today’s more distributed landscape of power, wealth, and authority. This will take time—decades, likely—but it must be done.

We find ourselves at a particularly difficult juncture. On one hand, we face a mounting global environmental crisis. On the other, we are undergoing a profound shift in the global distribution of power and wealth. These two forces may collide in unhelpful ways. If they do, we will fail to address the defining challenges of our time.

President-elect Donald Trump and Elon Musk at UFC 309 at Madison Square Garden. Photo by Jeff Bottari. November 16, 2024 / Zuffa LLC / Getty Images

But my optimism, such as it is, in the grim field of international relations lies in the hope that climate pressure may push us toward cooperation and institutional reform. If it doesn’t, it will only deepen divisions and spark more conflict.