Central Asia, the cradle of ancient traditions and a crossroads of diverse ideologies, cultures, and beliefs, has long captivated the imagination of travelers from both near and far. Through their detailed notes and vivid reflections, they have, for centuries, offered a unique, albeit not always impartial, glimpse into the rich mosaic of life in this region: bustling bazaars, nomadic customs, and enduring cultural heritage. In this series of articles, Qalam presents excerpts from their accounts and memories, spanning different eras and revealing the many facets of Central Asia.

Today, we present to you the notes on Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and Sarts by the renowned French traveler Marie de Ujfalvy-Bourdon.

Between 1876 and 1878, the famous French researcher and traveler Marie de Ujfalvy-Bourdon (1842–1904) participated in a major French expedition to Siberia and Central Asia with her husband Charles Eugène Ujfalvy de Mező-Kövesd (1842–1904), the prominent Franco-Hungarian ethnographer. She later chronicled her observations and experiences in her book De Paris à Samarkand, le Ferghanah, le Kouldja et la Sibérie Occidentale: Impressions de Voyage d'une Parisienne, published in 1880.

Ujfalvy-Bourdon’s book contains many fascinating recollections, particularly those related to the everyday lives of local people and the status of women. However, despite the firsthand information, the book is filled with the confusion and stereotypes typical of Russian and European ethnography of that period.

For instance, in her descriptions, the Kazakhs are often conflated with the Kyrgyz, and at times the Kyrgyz (then known as the Kara-Kirghizes) of Semirechye are mentioned as part of the Kazakhs, grouping them along with the three Jüzes and the Bukei Horde. She also writes:

The first horde is called the Kirghiz, while the others are commonly referred to as Kazakhs or Kaizaks. However, fundamentally, they are the same people. They speak the same language, share the same physical traits, and have the same customs, traditions, and even superstitions. The Kara-Kirghiz are the nomads of the mountains, while the others are the nomads of the plains.

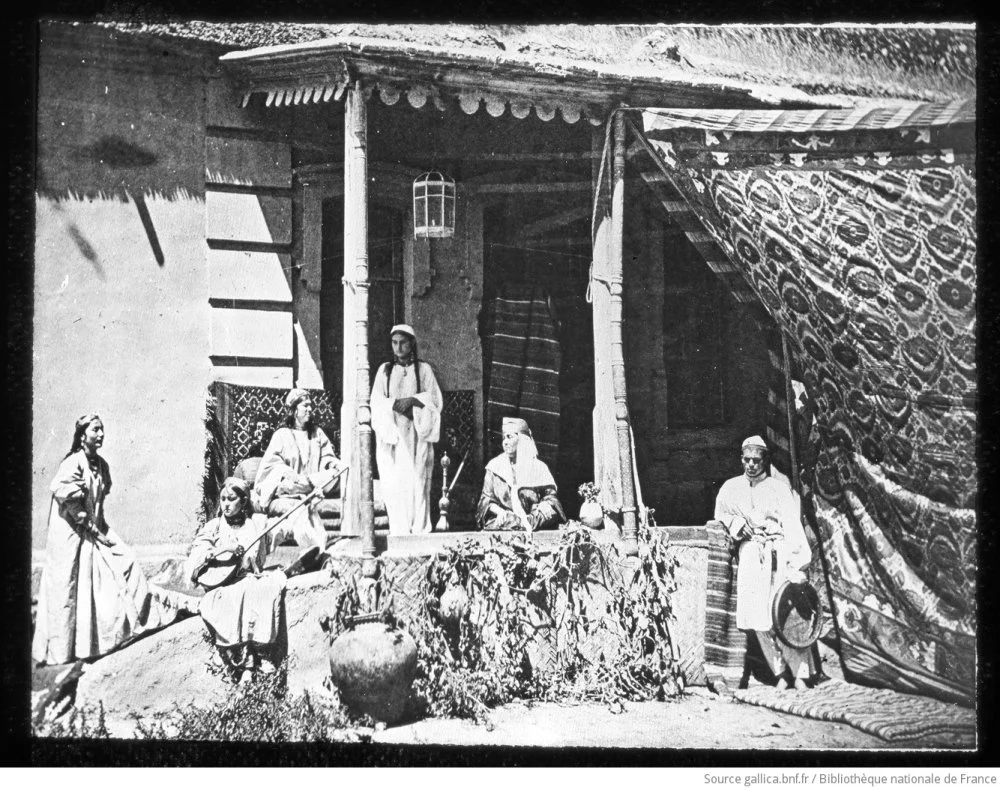

Charles Eugène Houyfalvy de Mezokovez (1842–1904). Sart Women in Turkestan, 1877–1880 / gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque Nationale de France

And this is how, not without a touch of irony, she describes the ‘gender balance’ in local families:

Among the nomadic Kazakhsi

Among the Sarts (inhabitants of the cities in Central Asia), it’s the exact opposite. Women concern themselves only with their appearance and do not lower themselves to household chores, which they leave to their servants. The husband is merely the chief servant—he sweeps, embroiders, and sews.

She also mentions the issue of domestic violence:

What a sight humanity is, always swinging to extremes, avoiding one excess only to fall into another. Here, I remarked, the man has all the rights, except the right to kill his wife; beating her, however, is acceptable—it’s seen as a small gesture of affection that rekindles love. Among certain Russian peasants, a woman doesn’t believe her husband loves her unless he has beaten her. Isn’t this yet another case of proving that all tastes exist in nature?

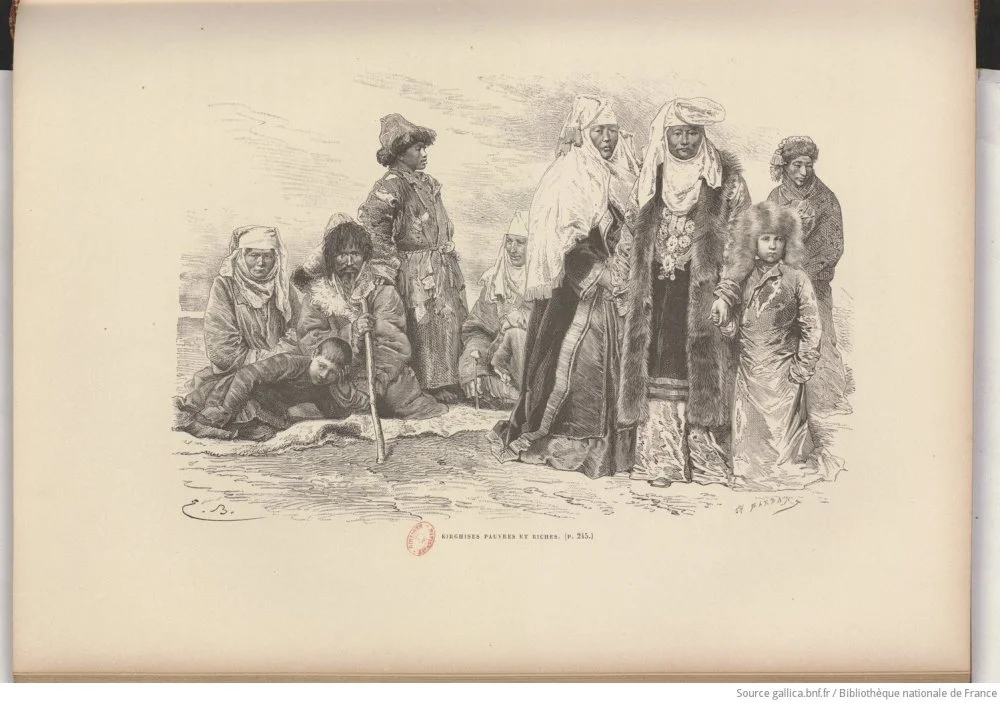

Emile Bayard. Engraving. Poor and rich Kazakhs. Illustration from Orenburg to Samarkand, by Marie de Ujfalvy-Bourdon. Between 1876 and 1878, in the Tour du monde, directed by Edouard Charton /Bibliotheque nationale de France

She does not overlook social inequality either and writes:

The wealthy Kirghiz are distinguished from the poor Kirghiz particularly in terms of their clothing; they are also cleaner and more meticulous in their appearance. The wealthy, who are often moneylenders, have devised rather ingenious methods to rapidly increase their wealth. For instance, they lend a poor man ten sheep; the following year, the debtor owes twenty sheep to his creditor, in the second year forty, in the third year eighty, and so on, to the point where the poor fellow can no longer repay his debt.

At this stage, the wealthy lender agrees to take the debtor into his service for a period of time considered equivalent to the obligations the debtor has undertaken. In this way, slavery, officially abolished by law, persists in reality under an even more insidious form. A clever application of the ancient Roman law!