In a course of lectures for Qalam, researcher Zira Nauryzbai delves into the mysterious world of Kazakh customs dedicated to the most important events in a person's life: birth, wedding and death.

Kazakh weddings sometimes seem too long, a complicated system of tois (feasts, parties), gifts, and rituals and in recent years, there has been a growing conversation about reforming or simplifying the format. Some couples simply choose to forgo the wedding, preferring to spend the money on travel. Each family resolves the issue in its own way, and in this lecture, we will try to approach the issue from a cultural studies lens.

Kazakh weddings are not limited to the wedding ceremony and festive banquet and are preceded by a vast series of rituals and events including but not limited to: qyz köru (choosing a girl ), jaushy zhıberu (sending a mediator), matchmaking, aittyryp syrğa salu putting (earrings on the bride), qūda tüsusu (another round of matchmaking), qalyñmal töleu (paying the kalym, which means ‘bride money’), jasau daiyndau (preparing the dowry), ūryn baru (‘secret’ trips the groom makes to the bride), qalyñdyq oinau (nocturnal meetings between the bride and the groom), qūda şaqyru (invitations from the matchmakers to the groom’s home village), neke qiyu (the Muslim marriage ceremony or nikah), qyz ūzatu (seeing off the bride), and the üilenu toiy (the wedding itself).

This is, however, a rather abbreviated list of events related to marriage in Kazakhs. Ethnographers count from 4 to 7 tois, including not only hosting a large number of people, but also baiga, kökpar, wrestling matches, archers, aqyns, singers, küishi. And such a toi extends over several days and receptions. For example, when the matchmakers are invited to the groom’s village, it is unseemly for the matchmakers to be entertained only in the groom’s parents’ house—it is imperative that they be invited to several homes of close relatives.

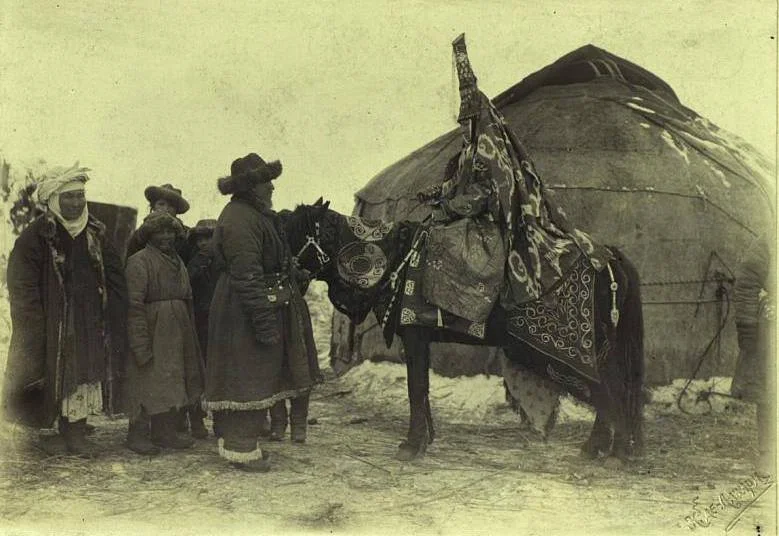

In the past, in addition to the main tois, the bride and her entourage also took a farewell trip to her relatives before the ūzatu, which can last several weeks. The bride’s train to the groom’s village had to be met and hosted by the villages along the way. And after the wedding, the young daughter-in-law, together with her husband and his young relatives, was invited by her husband’s relatives to the ‘showing the door’ ritual (esık körsetu), which involves both sides getting to know each other better and offering gifts to the daughter-in-law. These visits lasted an average of one year, and the daughter-in-law wore the most elaborate clothing, including her ceremonial hat (säukele), for such visits.

Bride In Saukele Kazakhs 19th Century/Alamy

Kalym: A Ransom or Gift?

In addition to the kalym, which consisted of several parts and included an average of 47 horses, the groom’s side at each stage constantly presented a lot of gifts — käde, which included cattle, pieces of cloth, clothes, pleasant trifles such as mirrors, combs, sweets, etc.

All these tois, rituals, gifts are so numerous that it is impossible to tell about them in one article. I will mention only a few important points.

A. Kasteev. Kolkhozny toy. 1937/The State Museum of Arts of the Republic of Kazakhstan named after A. Kasteev.

It should be said at once that the idea of kalym as a bride purchase is erroneous. It comes first from the texts of synsu (ritual lament of a bride before leaving her native village), in which the bride complains that her father sold her for kalym. But this is a peculiarity of the genre. Second, the theme of the bride sale emerges among democratically minded educated Kazakhs in the 19th century and then intensifies in the Soviet period in the context of the struggle for the “liberation” of women in the East, for women’s rights, and against reactionary traditions.

The bride’s dowry was usually not inferior to the value of the kalym and often exceeded it. It was a matter of honor for the bride’s family and influenced the young daughter-in-law’s position in the new family. Besides, it was easier to bring cattle for kalym than to prepare a good dowry, which included a yurt with all accessories — felts, carpets, furniture, a huge amount of clothes, bedding, dishes, jewelry.

Kazakhs 19th Century/Alamy

Even if the groom’s family was rich and could easily pay the kalym at once, Kazakhs never did. The kalym was paid in installments, and it took at least three years from the matchmaking to the wedding. On the one hand it was necessary to prepare the dowry, on the other hand the qalyñdyq oinau, i.e. the meeting of the groom with the bride in front of her house after the payment of the kalym, was considered the most beautiful period in the life of a girl, so good parents tried to prolong it.

Of course, there were cases when the kalym was advantageous to the bride’s family. For example, giving a daughter as a younger toqal wife or marrying a widower was not considered a very dignified deed for the family - accordingly, the kalym was larger. A poor family might agree to such a marriage in order to improve its own situation, to gather cattle in order to marry a son. The maximum duration of the payment of kalym after the contract was 12 years. If the groom’s side failed, the bride’s side could raise the issue of the future of the marriage.

Thus, kalym was not a purchase of the bride, but an exchange of kalym for dowry. It is characteristic that the groom’s side gave mainly cattle, hence the name qalyñ mal (lit. numerous cattle), and the bride’s side gave things made by hand, so to speak artifacts, hence the dowry was called jasau (lit. to make).

Kazakh Woman in Wedding Clothes on a Horse. Kazakhs 19th Century /Wikimedia Commons

Why is there a need for a secret meeting between the bride and groom?

When describing a Kazakh wedding, it is worth mentioning the rites that are now remembered only by ethnographers. After qūda tüsusuуi

Kazakhs 19th Century/Alamy

Ybyrai Altynsarin wrote in 1868 in his work Sketch of customs at matchmaking and wedding among the Kyrgyz of the Orenburg region:

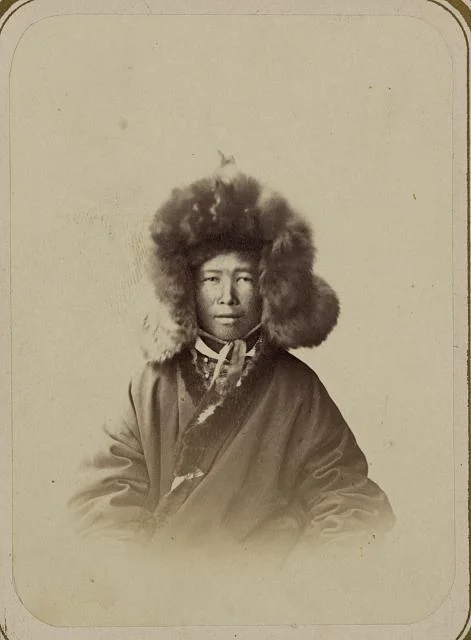

“The groom who goes to the bride is obliged to dress as richly as possible and ride on the best horse... The bridegroom cannot wear a hat (börık şyğar,) on his head, because his face is completely open in it, and the custom of Kyrgyz courtesy requires that the bridegroom’s face remain half-closed on such occasions; therefore, instead of a hat, he should wear a malakhai,i

The groom’s half-closed face evokes the custom of covering the bride’s face with a shawl or hiding it behind a curtain (şymyldyq) before the betaşar rite.i

So the groom “hides” near the village, and his entourage goes to the village to offer gifts. If they are accepted, then “two versts awayi

This moment is captured in a photograph from the Turkestan Album. The album was created in the 1860s by order of Konstantin von Kaufmann (1818-1882), the first Governor-General of Russian Turkestan. Any publication of the photo on social networks provokes heated comments: the men usually resent the photo and consider it fake or staged. They do not accept quotations from ethnographic works. However, Ibrai Altynsarin notes in his book that even in his time, in the mid-19th century, the groom’s täjım was a disappearing rite that “smart Horde men” tried to avoid. The ever-increasing male ego made them forget the ancient custom, although videos of such a rite sometimes appear from the southern region.

As it is stated in the multivolume encyclopedia Traditional system of ethnographic categories, terms and names among Kazakhs,i

A groom bowing to the bride and her family. Turkestan Album/Wikimedia Commons

Going back to the ūryn bar. The young may not like each other, or the behavior of the groom may not please the women of the village. The 19th century historian Kurbangali Khalidi quotes the words of batyr Barak about the ūryn trip:

“I was never afraid in battle, surrounded by numerous enemies, but I felt fear when I came to the bride’s village and saw the women gathered. For enemies can be resisted, while the bridegroom, according to custom, can only bow his neck before the women. What can you do if one of them strikes you on some pretext?”

Incurable diseases, congenital defects discovered during the visit gave the bride the right to refuse the marriage. In the course of my work I sometimes read añyz, şejıre, and other kinds of oral literature. I remember a legend from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. The bride sees that the bridegroom is unattractive, does not know how to behave, does not know etiquette, but she accepts it. Suddenly she discovers that he is also hard of hearing. She is outraged:

“How can I tell him the inmost things, the whole village will hear.” So she breaks up with him. Such a funny and sad story.

During the ūryn, the girls and young women of a village, after bowing to the groom, begin to banter with him and his retinue, testing his wit, his reading knowledge, his etiquette, challenging him to aitys.i

In his book My Family about his childhood in the early years of Soviet rule, the warlord and writer Bauyrzhan Momyshuly describes with ethnographic accuracy the wedding of his older sister. Although the sister was already 20 years old, i.e. almost an old maid by the standards of the time, she had already caught a glimpse of the bridegroom and agreed to the marriage, but when the bridegroom arrived too hastily in her village, she drove him away with all the gifts, resenting that he had hurried his visit without her consent. At the second attempt, the embarrassed, simple-minded groom was unable to respond wittily to the women’s jokes. When the bride found out, she refused to meet him. She was barely persuaded to arrive at the yurt set up for the groom at dawn. The groom, intimidated by the women’s jokes and tired, had dozed off and failed to meet the bride and bow to her properly. As a result, she chased him away and announced that she would refuse to marry him. Since she had previously refused a groom and her family had spent a great deal of money preparing a dowry, her father insisted on this marriage. The groom was trained in his village for a long time for the third visit, taught small talk and jokes, and the bride’s relatives were asked by her father not to attack him too eagerly. Thus, the third attempt of ūryn was more or less successful, and the marriage finally took place.

In the custom known as “The Old Woman Has Died,” one of the elderly women in the village falls in front of the groom, while the other women shout, “Oh! The old woman has died!” She is “brought back to life” only after receiving a gift/Wikimedia commons

When the groom comes to pick up the bride, the father-in-law formally invites the son-in-law to his house before saying goodbye to the bride (ūzatu). In some ethnographic works this is reported to take place before the first wedding night, in others after. Upon entering the house, the groom bows to the ground three times — to the aruaqs,i

“Mother Umai, Mother Fire, give us your blessing!”i

For this ritual he gives a gift (käde) of five sheep. The bride’s parents give the groom a şapan (gown) as a bride-show present (körimdik). He is not seated in the place of honor (tör), but in a place at the junction of two kerege — the sashes of the yurt, symbolizing the union of the two clans. The son-in-law never sits on the tär, even if he is old or respected. The bride is then taken to the parents’ house, and the marriage ceremony is performed.

Let me note that, judging by the groom’s bowing to the bride’s female relatives during the uryn and the rites performed during the groom’s first visit to his father-in-law’s house, in the mid-19th century not only the bride entered her new clan. Before her, the groom went through similar rituals to become his own in the bride’s clan. It is not without reason that Kazakhs say that a man has three clans — the clan of his father, the clan of his mother, and the clan of his wife. These rituals are relics of the ancient matrilocal marriage, when not the daughter-in-law was a member of her husband’s clan, but the husband lived in his wife’s clan. It is believed that the expression küşik küieu (lit. son-in-law-puppy) comes from küş küieu (lit. son-in-law-force), i.e. a son-in-law who earned his wife not by kalym, but by working for her family for several years. This was the custom of the Borjigin family at the time of CHinggis Khan. The great conqueror, according to American researcher Jack Weatherford, was categorically against replacing the custom of küş küieu with kalym.

Showing a Kazakh couple, noble or wealthy. Beteeen 1870 and 1886/Alamy

What do wedding and war have in common?

Another interesting aspect of Kazakh wedding traditions is aggression in various forms, war symbolism. For example, jauşy is a messenger for preliminary negotiations on matchmaking. Jauşy, as the word itself (the root jau means ‘enemy’) says, is a messenger to inform about the war that has started. The saying goes:

Jauşy stirs up hostility, elşı reconciles.i

It seems that the person sent by the groom’s party to learn more about the bride’s family and to gauge her attitude toward a possible marriage should be called elşı (an envoy, from el — ‘people, country, clan’) rather than jauşy. The groom is attacked during ūryn baru, and later, into old age, he endures the teasing of his wife’s younger brothers and sisters (baldyz). The night before the bride’s departure, the bride’s relatives try to open the felt on the newlyweds’ yurt, and this rite is called “dismemberment of the house” (üi müşeleu).i

Competitions of aqyns (folk poets; aitys) and of musicians playing various instruments (tartys), banter during the matchmaking process, and the matchmakers’ visit to the groom’s village are fun, but they also contain obvious elements of verbal aggression. And not just verbal. In the bride’s village, the people suddenly attack the matchmakers, smearing their faces with liquid dough, lime, clay, soot, trying to throw one of the qūda (matchmakers) into water, a cellar or a pit filled with mud, pulling a woman’s scarf (jaulyq) over her head, tying the matchmaker backwards to a bull’s back and chasing the bull into the steppe, tying up the smeared matchmaker with a rope and lifting him up on a şanyrak, giving the qūda a drink of unfermented koumiss or liquid dough üpilmälik to upset his stomach, and then mocking those who run to the bushes, making him walk on all fours, and riding on him. In comparison, the rites of arqan keru (pulling a rope across the road to get the ransom) and sewing the hem of the qūda’s clothes to the blanket (körpe) from behind seem no more than childish pranks. During the bride’s return visit to the groom’s village, this friendly matchmaking continued.

Groom. Turkestan Album. 19 century/Congress Library

On the one hand, such an attitude to respected qūda during matchmaking is a phenomenon that in science is called the reversal of social structures, carnivalism (see, for example, the works of Mikhail Bakhtin). It is a short period in the life of society, when the forces of chaos break into ordinary life, violating the accepted laws and proprieties. As a result, purification and renewal take place, society receives new energy, and a new harmony is created. Usually this happens when one time cycle ends and another begins, such as a new year. Here the new cycle is the creation of a new family.

On the other hand, it is an obvious aggression against the members of the other clan. There are endogamous peoples, among whom marriage takes place within the clan. Kazakhs are an exogamous people, i.e. their marriages are concluded only between representatives of different clans. In ancient times, exogamous marriages are believed to have occurred as a result of violence, kidnapping, or war. Over time, this violence disappears from the life of the society, but on a subconscious level, the idea of one clan taking a member of another clan remains and provokes aggression.

The Nobel Prize winning biologist Konrad Lorenz has written a very interesting book called Das sogenannte Böse. Zur Naturgeschichte der Aggression (Aggression, or So-called Evil, known in English as On Aggression) about aggression in animals. The scientist explains that in the animal world, individual relationships, including love and friendship, arise only in species characterized by intraspecific aggression. These species are forced to develop powerful rituals to inhibit, redirect, or ritualize aggression. Interestingly, Lorenz’s study focuses on the totems of the Kazakhs: the wolf, which he calls the most aggressive animal, and the goose, the most aggressive bird, and their rituals for redirecting aggression. Modern zoologists partly dispute this concept of Lorenz, but in general it retains its importance.

The woman is holding a whip and is looking back at the men. May be an example of the tradition of capturing or "kidnapping" a bride. Turkestan Album. 19 century/Wikimedia commons

Surprisingly, the zoologist’s thoughts are confirmed by a researcher of a completely different field, a representative of European intellectual traditionalism, a researcher of Islam, Hinduism and North American Indian traditions, Fridtjof Schuon. In his book Logic and Transcendence he discusses the main values of the warrior caste (Kshatriyas) — honor, virtue, glory, nobility. I would like to remind the reader that together with my late husband, küişii

Frithjof Schuon characterizes the psychological type of the Kshatriya (warrior) as intellectual, but at the same time active, passionate, emotional, strong, aggressive. The warrior compensates the aggressiveness of his energy with generosity, and the passionate nature with nobility, self-control, and magnanimity. In other words, the zoologist and the philosopher are saying the same thing in different words. Natural aggression is softened, restrained by ritual and generosity, and takes the form of a game.

Rather crude jokes about matchmakers are not only an echo of a very old time when exogamous marriage became more peaceful. Note: Male matchmakers are attacked by the jeñge (wives of older brothers), sometimes with the support of young men from the village. This, like the groom’s bowing to the bride’s female relatives, is a rudiment of matrilocal marriage: women “protect” the space of the clan and the village from outsiders. They are assisted by jigits, the sons of the clan.

Kokpar. Turkestan Album. 19 century/Wikimedia commons

Wedding as Networking and Team Building

In Kazakh wedding tradition, the only thing that comes from Islam is the rite of neke qiyu (nikah or marriage), and even then, the bowl of neke su (lit. “water of marriage”), over which a prayer is read and from which the groom and witnesses drink as a sign of the contract, is a legacy of the ancient Turkic people. Matchmakers and groom endlessly perform rituals and distribute käde. As the saying goes:

“There may be a bride without a kalym, but there is no bridegroom without a gift.”i

During the ceremony of ūryn baru and qalyñdyq oinau alone, there is a huge nomenclature of the groom’s gifts (käde): a gift for showing the tent (şatyr baiğazy), a gift for seeing the bride’s younger relatives (baldyz körımdık), qyz körseter (seeing the bride), qol ūstatar (touching with hands), şymyldyq aşar (opening the veil), şaş sipatar (stroking the bride’s braid), körpe qimyldatar (putting to bed, lit. ‘moving the blanket’). Qol ūstatar on one of the first dates is particularly interesting. The bride is in her parents’ house on the right side of the tör (place of honor in the yurt), on her bed. The felt covering of the yurt (tūyrlyq) in this place is raised, the young touch with their hands through a white silk shawl. That’s Kazakh romance for you.

In one of the variants of the epic Qobylandy, the batyr (hero) says to his younger sister:

“I received and brought you a jenge without kalym and gifts.”i

But this is an exceptional case: the batyr got a wife as a result of winning the bridegroom competition. With all his extraordinary wisdom, beauty, and high origin, Qūrtqa is almost a trophy for the batyr, and this affects their relationship, Qūrtqa’s relationship with the father-in-law.

Kolustatar tradition. 19 century/Wikimedia Commons

As Ybyrai Altynsarin writes, since the time of Esım Khan,i

Complex rituals lasting several years, numerous tois, and generous gifts were required not only to create a new family, a new microcosm in which the bride belonged to the groom’s clan and the groom to the qaiyn jūrt (wife’s clan). It was also a matter of getting to know these people and bringing them closer together, creating strong, reliable bonds between two ambitious clans, so that the matchmaking was really a millennium long, as the saying goes. It was Kazakh networking and team building.

In a warlike nation, “Heroes do not unite until they face each other in battle.”i

The traditional Kazakh wedding is a duel-like competition between two marrying clans. They compete in generosity, nobility, sports, craftsmanship, generosity and wit, in musical and poetic art. Here the essence of traditional warrior culture is clearly manifested as a ritualization and reorientation of aggression in a playful form.