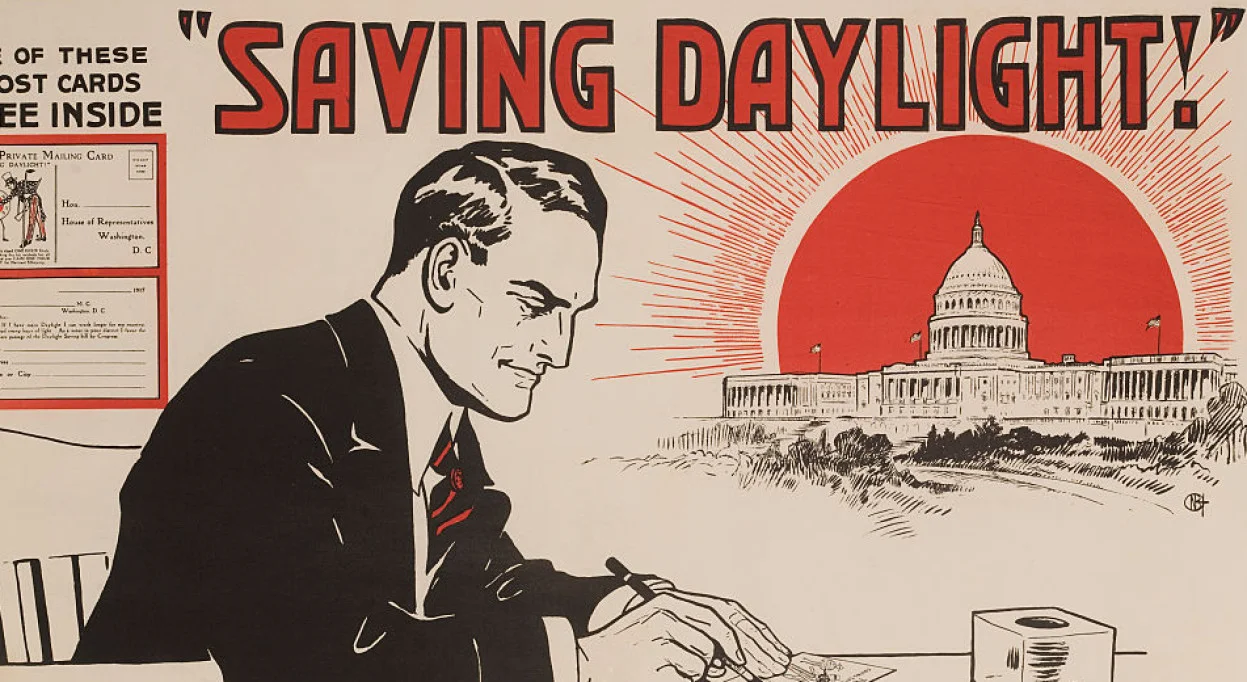

Businessman writing card to his Congressman offering his support of daylight savings. ca 1917, produced by the United Cigar Stores Company/Photo by David Pollack/Corbis via Getty Images

In late October, many countries will turn back the clocks, marking the end of daylight savings time. As winter approaches, putting our clocks back by an hour allows for brighter mornings but earlier sunsets. And each year, this shift brings up new debates about whether we should adjust our schedules or not. Let’s find out more!

For most of human history, people have lived happily without tracking time by the hour. However, as ancient civilizations developed and large cities came into existence, efforts to organize space and time began, leading to the creation of various primitive clocks, such as water clocks, sundials, and hourglasses. But despite various advancements in mechanics and astronomy, most people structured their lives almost entirely around the movements of celestial bodies until the last two centuries.

Church bells called people to morning prayers, muezzins climbed minarets at the first glimmer of dawn, and religious fasts began and ended with the daylight (‘No food until the first star appears’ or ‘Until the black thread is indistinguishable from the white’). The fact that daylight hours vary throughout the year, and more so the farther one is from the equator, could be largely disregarded in simpler societies. Daybreak meant it was time to rise and work, while nightfall signaled that it was time to sleep. In summer, people slept less; in winter, they caught up on rest.

Even in ancient Rome, with its million-strong population and well-developed services, there were two distinct ways of perceiving time: summer and winter. The Romans addressed this variation in a fairly simple way: daytime hours were longer in summer and shorter in winter. At the solstices, an hour could last anywhere from forty-five to seventy-five minutes. Special officials managed these calculations, and town criers announced the correct time in public squares.

The poster issued by United Cigar Stores Company in the United States to promote daylight saving time in 1918 during World War I/Wikimedia Commons

However, with the development of northern civilizations and especially the onset of the Industrial Revolution, the question of seasonal time adjustments became much more pressing. Lighting urban streets, workshops, and private homes had already become a significant expense long before the advent of electricity. In 1784, Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, as well as a scientist and inventor, wrote a satirical essay while serving as an ambassador to France. In it, he urged Parisians to stop wasting candles and to adjust the clocks for winter and summer so that people would rise earlier and go to bed as soon as it got dark. Besides saving candles, Franklin also advocated for conserving wood used for window shutters, suggesting that shutters be banned altogether so that the sun would wake those who slept until noon. Better still, he proposed firing cannons and ringing all the bells each morning to rouse all of Paris—let the city rise early and avoid burning candles until midnight at balls and card tables! It’s worth noting that this essay was meant as a joke, but as we know, every joke holds a grain of truth.

David Martin. Benjamin Franklin. 1767/Wikimedia Commons

We know that a similar proposal was considered during Napoleon's time. Yet, the general, who was supportive of large-scale reforms, such as legal, calendar, and metric changes, ignored this particular suggestion. Nevertheless, the idea took root and spread. Articles and proposals on the topic began appearing in publications around the world. It should be noted that while the idea of daylight saving time had well-known supporters, there were also fierce opponents. For example, George Darwin, grandson of the famous biologist Charles Darwin, wrote:

‘Even Parliament is incapable of changing the relative positions of the Sun and Earth. It can only decree that all clocks in Britain show the wrong time for five months of the year.’

The first country to adopt daylight saving time was Canada. On 1 July 1908, in the city of Port Arthur, all clocks were ceremoniously set one hour ahead. Other Canadian cities soon followed. After the First World War, daylight saving time was introduced in many countries, including Germany, Russia, and the United Kingdom. It was believed that shifting the clocks would mean significant energy and fuel savings on lighting.

However, calculations conducted in the twenty-first century have repeatedly shown no substantial energy savings from such measures: these studies report only 1–2 per cent savings on average. On the other hand, changing the clocks leads to periods of increased accident rates, especially in the transportation sector, where system failures often occur due to the disruption of schedules and routes. Health statistics also reveal adverse effects: many people experience the shift in their usual routine as a source of stress, which can lead to circulatory system complications and other unpleasant health consequences.

Senate Sergeant at Arms Charles Higgins turns forward the Ohio Clock for the first Daylight Saving Time, while Senators William Calder (NY), William Saulsbury, Jr. (DE), and Joseph T. Robinson (AR) look on, 1918. U.S. Capitol building, Washington, D.C./Alamy

Currently, sixty-six countries observe daylight saving time, but this number is steadily declining; in the 1990s, ninety countries followed the practice, and the countries that have opted out include China, Japan, India, Russia, Kazakhstan, and most of South America.