Women, encroaching on the sacred right of men to wear trousers, did not violate the most ancient traditions at all. Because, it seems, these traditions did not exist at all.

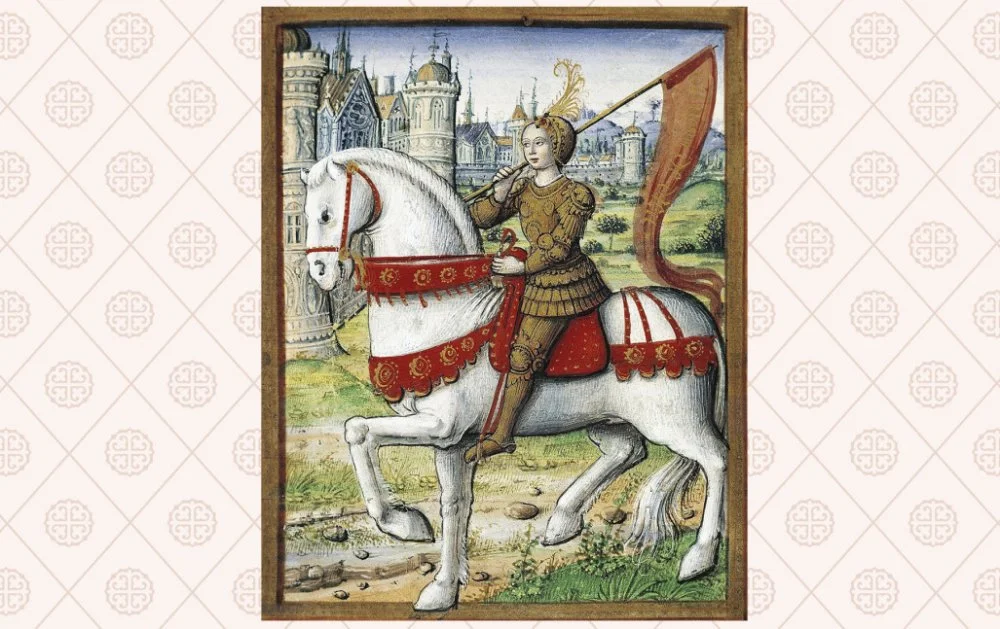

Jean Pichore. The lives of famous women. Jeanne d'Arc is depicted riding a horse. 1504-1506/Wikimedia Commons

Around a century and a half ago, simplicity in clothing was the norm. Skirts and dresses were reserved for girls, while short pants were for boys who had outgrown their baby clothes. A woman wearing pants was deemed socially improper, and although Joan of Arc wasn't executed for wearing pants, it was counted among her many transgressions. Despite this, from Joan's era onward, at least two European empresses have dared wear pants—Queen Elizabeth I of England and Empress Elizabeth I of Russia. Both donned military uniforms that included this entirely masculine garment. The Russian empress was even captured in this attire in portraits. Of course, having royal status definitely rendered them exceptions to the rule.

In general, a young lady in trousers was a terribly indecent sight. To witness such a spectacle, one had to attend the theater. ‘Here was Miss Snevellicci; she could perform anything, from any dance to Lady Macbeth, and for her benefit performances, she always played a role in knee-length blue silk trousers,’ wrote Charles Dickens in The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby.

But why did women start wearing pants—an inherently masculine garment, seemingly unfit for the female form— at all in the twentieth century? Interestingly, there is a response to this rhetorical question: women did so for the same reasons that drove men to wear trousers—they began engaging in activities where pants offered greater practicality.

Paul Delaroche. Hémicycle. 1841/Wikimedia Commons

Investigating the Origins of Trousers in Ancient Civilizations

If we were to employ an imaginary magnifying glass over time and closely inspect the daily lives of the great civilizations of antiquity, we would be taken aback by the array of items that we typically associate with modern times—things we wouldn't anticipate encountering within the depths of the ages. Sunglasses, liquid soap, dental prosthetics and moist towelettes, toilet paper, and deodorants, and so many more! In their quest for comfortable and practical living, denizens of the ancient eras were strikingly similar to us, swiftly devising articles that facilitated such comfort.

Nevertheless, certain aspects of this tableau would conspicuously elude our observation. Take, for example, pants.

Ancient Egyptians were usually seen in their linen garments, loincloths, and tunics. Equally, ancient Greeks sported leather miniskirts. Phoenicians draped themselves in tunics. Romans were robed in togas. Mesopotamians were adorned in floor-length robes. The Chinese, who wore no shoes, wore robes and undershirts (during severe winters, they would attach leggings to their waist with cords—not quite pants but a precursor). Meso-American men, once again, donned skirts, while only a few northern tribes donned leg coverings beneath their shirts and dresses. They wore dhotis in India and sarongs in Indonesia.

Where were the pants? Where was this truly traditional item of men's attire visible? Was it really so difficult to come up with regular trousers with a crotch seam and a string for fastening around the waist?

We can, in fact, unearth these very pants in the pages of history. As documented by contemporaneous records, such as those penned by Herodotus, as early as the sixth to fifth centuries BCE, this authentic barbaric attire adorned the Medes and, subsequently, the Persians. Ancient historians opine that the Persians assimilated this uncultured attire from the Medes. The Medes, in their tradition, were accused of the rather undesirable practice of donning ‘feminine attire’. Their descendants, labeled ‘Sarmatians’, were characterized by Pliny the Elder as the progeny of Amazons and were referred to as ‘governed by women’.

Pants, in fact, were a familiar sight in the ancient world. They simply weren't commonly displayed to the world as they were concealed beneath long dresses worn by women within households. Women's pants, known as a shalwar, were prevalent across the Near East, from Mesopotamia and Persia to India. Shalwar kameez, the contemporary attire from Punjab, is the direct descendant of an ancient garment that was long considered exclusive to women's clothing in these regions. Due to various physiological factors, pants offered many conveniences for women, serving as an additional barrier for hygiene and modesty. Pants were an attire unaffected by even the most forceful winds and thus ensured modesty in all circumstances.

However, for men, these conventions were superfluous, especially for those not engaged in equestrian pursuits.

Lionel Royer. Vercingetorix throwing down his weapons at the feet of Julius Caesar. Musée Crozatier in Le Puy-en-Velay. 1899/Wikimedia Commons

Pants Were Not for Civilized Society

Indeed, for a considerable time, pants were viewed as primitive and immodest clothing. This was primarily due to their prevalence among nomadic groups. Naturally, this did not apply to all nomads and only to those who rode on horseback. This specific mode of transportation hastened the rapid evolution and adoption of pants. No loincloth, nor even the softest chaps, will prevent the transformation of highly important body parts into bleeding blisters if one spends a long time riding a horse while wearing a skirt. The oldest pants in the world, dating back around three thousand years, were discovered at a burial site in the Xinjiang-Uyghur region (China), which was inhabited by nomads at that time, causing much trouble for the rulers of Chinese kingdoms with their raids.

The grand civilizations of the ancient world achieved their prominence through sedentary lifestyles, city construction, palace establishment, aqueduct creation, and library development, with infrequent engagement in horseback riding. Despite humans domesticating horses in around 4000 BCE, these animals remained unsuited for riding due to their frailty and diminutive size. They served primarily as draft animals. Horses were harnessed as living propellers of carts in daily life and chariots during warfare. A horse-mounted warrior in ancient times would have been an anomaly on the battlefield. A small and moderately paced horse would not enhance maneuverability but would impede the ability to wield a bow or spear. The absence of stirrups and saddles at the time made secure horseback riding impossible while simultaneously engaging in combat.

However, chariots were a different story. The belief that war chariots originated and flourished in Mesopotamia endured, yet recent archeological findings propose an alternative birthplace—India. A tomb dated to around 2000 BCE was recently discovered in India, revealing a remarkably well-preserved bronze chariot. Coincidentally, this discovery added fuel to the debates regarding the dating of the great Indian epic the Mahabharata. The varying dating of the epic by several thousand years introduced arguments, one of which was spurred by the depiction of Arjuna's chariot, helmed by Krishna, where the deity volunteered to serve the great Pandava as a humble charioteer during their righteous battle.

Regardless, the ancient world didn't hinge its reliance on horsemen; rather, it favored chariots. Around the seventeenth century BCE, the Hyksos employed chariots to conquer Egypt, and subsequently, Egypt employed them to defeat the Hittites. Even King Solomon, with his 1,400 chariots, made an appearance, while Automedon, the charioteer, achieved astonishing feats with his unstoppable horses beneath the walls of Troy. And when it came to combat from a chariot stance, pants were entirely dispensable. As such, men in ancient civilizations managed adeptly without this extravagance.

Brothers Lesueur. Prison tribunal. 1792/Wikimedia Commons

Triumph and Work Trousers

It required hundreds, even thousands, of years of practice for mounted warfare to be fully realized. New breeds of taller, more robust horses emerged, along with new weaponry, yet the armies of antiquity did not promptly embrace cavalry. For quite some time, cavalry remained secondary to the heavily armored infantry, the central pillar of ancient armies. Even Alexander the Great's Companion Cavalry and the cavalry of ancient Rome were auxiliary forces that, in critical engagements, dismounted and fought on foot. During marches, horsemen predominantly walked, adjusting their pace to the infantry, leading their warhorses unburdened.

Nomadic groups like the Scythians, Germans, Thracians, and Huns fought in distinctive ways. They predominantly served as mounted archers and spearmen, effectively living on horseback and even donning unconventional and immodest attire—pants. Romans situated along the Black Sea, in Britain, or near Cologne, recognized the benefits of light cavalry, encompassing its practicality in terms of clothing, which prompted the introduction of pants in Rome. But the appreciation for pants extended beyond merely cavalrymen. This transformation transpired during the first centuries of the common era, coinciding with the conclusion of the classical climatic peak and the onset of colder weather. The notion of warm pants beneath togas and cloaks seemed appealing to those who spent considerable time outdoors during winter, vending flatbreads on the streets, maneuvering masts at sea, contending with sails, or partaking in public debates at forums.

Consequently, during the fourth century, the emperors Theodosius and Honorius found themselves repeatedly issuing decrees and novellas to remind Roman citizens that wearing pants in Rome was forbidden; only various barbarians—the Gauls—were permitted to do so. Roman citizens were expected to attire themselves in tunics with cloaks or, ideally, togas, representing authentic Roman apparel. If the maintenance of snow-white togas was exceedingly inconvenient and expensive, then that dilemma rested on the Romans.

However, with the advent of a nearly modern-style stirrup, originating in China in the late third century, the integration of pants became an inexorable fact of human life. Thanks to the stirrup, horsemen could now shoot bows while standing in the stirrups, engage in sword fights, deploy shields, and wield spears. The cavalry evolved into an exceedingly critical facet of military operations, challenging the predominance of infantry and rendering the transition from male skirts and dresses to pants merely a matter of time. Naturally, certain steadfast cultures regarded pants as a feeble testament to the erosion of genuine masculine spirit. The Scots come to mind, yet as the centuries progressed, such champions of traditional values dwindled in number.

However, across Europe, trousers of all kinds long stood as military or work garments, while formal and respectable appearances demanded floor-length dresses. Between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, the formal upper attire gradually shortened, and men took to wearing chausses fastened around the waist over a hip wrap. Atop the hip wrap, they donned short pants-like pieces known as ‘puffs’. These chausses evolved into leggings and hose—apparel intended for equestrian pursuits—while the puffs expanded, metamorphosing into diverse forms of breeches and culottes. Eventually, the common populace wholly transitioned to long, comfortable work pants, which continued to denote laborers from the lower echelons. Remember that French revolutionaries were dubbed ‘sans culottes’ (‘without breeches’), indicating those who abstained from wearing aristocratic short breeches and lengthy coats, opting for rough, lengthy pants instead.

The normalization of men donning pants took place between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, although not everyone embraced the trend. Individuals such as non-warriors and those who did not engage in strenuous labor—priests and monks, for instance—continued to avoid inappropriate pants, opting for dignified, extended robes (a practice still followed by many to this day).

The label of ‘immodest attire’ lingered only for those audacious women who dared to don pants. However, this was predominantly the case in Europe; conversely, women in the East had been wearing various forms of trousers for an extended duration. Notably, Japanese women wore hakama pants throughout history, mirroring their male counterparts. In China, during the Tang dynasty (ninth to tenth century), pants had already become emblematic of the labor of peasant women, akin to being barefoot. Solely noble or affluent women enjoyed the privilege of wearing platform shoes and long dresses with trains, which was supported by attendants.

A group of models in the Place de la Concorde showing off their flared trousers. February 21, 1933/Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

European women had to await the advent of the First and Second World Wars. These wars, mobilizing numerous women to work in factories and even on battlefronts, transmuted trousers—highly suitable for work and movement beyond the confines of the home—into an article of female clothing. Skirts, prone to getting entangled in machinery, obstructive while scaling poles and electrical lines, and incompatible with fitting into tractor cabins, proved impractical during those demanding days. Rosy the riveter and her counterparts warmly embraced jumpsuits and jeans.

Therefore, women wearing trousers did not signify a decay of society due to moral corruption. On the contrary, it was the complexities of an evolving life that impelled the female gender to adopt this uniform of toil, perseverance, and the march of civilization.