In the early-eighteenth century, John Castle, an eccentric Anglo-German artist turned self-styled diplomat, embarked on a daring journey across the volatile steppes of Central Asia. Ostensibly part of Russia’s Orenburg Expedition, Castle was driven by a burning sense of personal mission and a taste for adventure, which, at times, may have colored the precision of his recollections. Nonetheless, his account remains one of the most vivid early European portraits of Kazakh life, politics, and diplomacy.

- 1. A Prelude to Disaster: The Dzungar Invasion and Kazakh Displacement

- 2. Between Steppe and Empire: Abulkhayir’s Russian Dilemma

- 3. Who Was John Castle?

- 4. Whispers of Rebellion: The Shadow of an Ottoman Plot

- 5. The Khan and a Curious Englishman

- 6. A Portrait and a Mission: Diplomacy in the Steppe

- 7. The Great Feast and Empty Plates: Customs and Misunderstandings

- 8. From Honour to Humiliation: The Long Road Home

- 9. Fact, Fiction, and Ethnography: Castle’s Enduring Legacy

A Prelude to Disaster: The Dzungar Invasion and Kazakh Displacement

Just over 300 years ago, in 1723, an invasion of Kazakh lands from the east by Oirats, more commonly known as Dzungars, led to events that have since become known in Kazakh history as Aqtaban shubyryndy, or the ‘Great Disaster’ or ‘Barefooted Flight’.

The Oirat incursion through the Ili Valley into the southeast of what is now Kazakhstan resulted in a massive displacement of Kazakh tribes and the seizure of the cities of Turkistan, Sairam, and Tashkent, which the Oirats held until 1758, when they were finally crushed by the Qin. All three Kazakh jüz (hordes) were affected, with the Kishi jüz (Junior jüz) fleeing en masse from their traditional grounds toward the northwest and the borderlands of Russia, and many members of the Uly jüz (Senior jüz) and Orta jüz (Senior jüz) heading south toward Samarkand and Bukhara.

John Castle. Presumably portrait of Khan Abulkhair / Tretyakov Gallery / Wikimedia Commons

And we know that a few years later, in 1726 and 1730, Abulkhayir Khan (circa 1680–1748) of the Junior jüz, having fled with his people to the northwest, entered negotiations with the Russians over the acknowledgement of formal suzerainty in exchange for protection from further Oirat attacks.

Between Steppe and Empire: Abulkhayir’s Russian Dilemma

A precise account of what happened following the Oirat incursion is still the subject of much debate. In particular, the Junior jüz’s decision to migrate away from the frontline, despite Abulkhayir’s successes in battle against the Oirats at both Bulanty in 1727 and Añyraqai in 1729, is hard to explain. Undoubtedly, the fate of the 400,000 people he led northwest from Turkistan along the Syr Darya River to new pasturelands in the Yaik (now Ural) and Tobol rivers regions must have been at the forefront of his mind.

By October 1731, Abulkhayir, his sons Nuraly and Eraly, and various senior advisers had sworn an oath of allegiance to the Russian empress Anna Ioannovna in exchange for military protection, even though there were deep divisions within the horde. Khan Semeke from the Middle jüz swore a similar oath in 1732 and the Senior jüz followed suit in 1733.

Presumably portrait of Sultan Eraly / Tretyakov Gallery / Wikimedia Commons

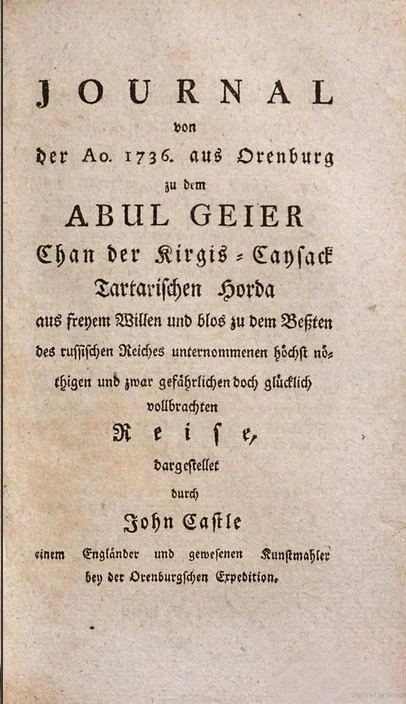

It is now clear that the precise meaning of these oaths sworn by Abulkhayir and the other khans was unclear. This article, however, is not the place to resolve these outstanding historical questions, already the subject of much study. But a remarkable book written by a rather unusual English adventurer and artist named John Castle may help cast some light on what happened and may also provide insights into what Abulkhayir was thinking at the time. His book, first published in German in Riga in 1784, remained in obscurity for many years. It was published in Russian translation only in 1998 and finally in English in 2014.

Who Was John Castle?

John Castle, to say the least, was a bit odd. Born to an English mother and a German father, he was probably brought up in Hamburg. It is said that he chose to present himself as English because he thought it would benefit him in business transactions. Biographical details about him are sparse, but we know that he joined the Orenburg Expedition in 1734 and may have spent part of 1735 in Bashkir lands along the Volga. This military expedition, sanctioned by a decree by Empress Anna Ioannovna, was directed to build a fort and trading centre at Orenburg with the aim both of stabilizing the southern border by suppressing Kazakh and Bashkir raids into Russia and opening up trade with Bukhara, Badakhshan, and India.

In the unpublished introduction to his journal, in which he describes himself as an artist with the Orenburg Expedition, Castle says that he made his journey to meet Abulkhayir entirely of his own free will and at his own expense. He writes that while he was staying in Orenburg in 1736 he met Eraly Sultan, the khan’s eldest son, who, having taken part in the Junior jüz embassy to Saint Petersburg in 1732, was being held there as an amanat, a ‘diplomatic hostage’, to ensure his father’s good behaviour.

John Castle. Sultan Eraly, a Bukharan akhun (poet), and the chief servant Kuder Batyr in full armor. Illustration from the book «Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde»

It is possible that Castle was inspired by the signing of a commercial treaty between Britain and Russia in 1734. John Elton, who suggested opening up trading relations with the Persian Empire across the Caspian Sea, was also a member of the Orenburg Expedition and traveled with Castle to Persia in 1743. In fact, Elton saved Castle’s life after Nadir Shah ordered him to be strangled for not producing portraits of him quick enoughi

Whispers of Rebellion: The Shadow of an Ottoman Plot

In June 1736, a delegation from the Junior jüz arrived at Orenburg with a letter for its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Yakov Chemodurov. The envoys wanted to know if Orenburg was still a military priority for the Russians or if there were plans to abandon the town. Castle says he invited the envoys, along with Eraly Sultan and a mullah, to his house, where they told him that the Ottoman Turks in Constantinople were trying to raise a coalition of Kazakhs and Kalmyks to attack the Orenburg Expedition. Interestingly, the Kalmyks, who had migrated from Western Mongolia to the lower Volga region in the seventeenth century, were closely related to the Oirats. According to Castle, Abulkhayir, anxious (or so he let it be known) to forestall the alliance, wanted an official Russian envoy to appear in the steppe to demonstrate the Russian determination to crush any rebellion. It is just as likely that he sought to measure their resolve.

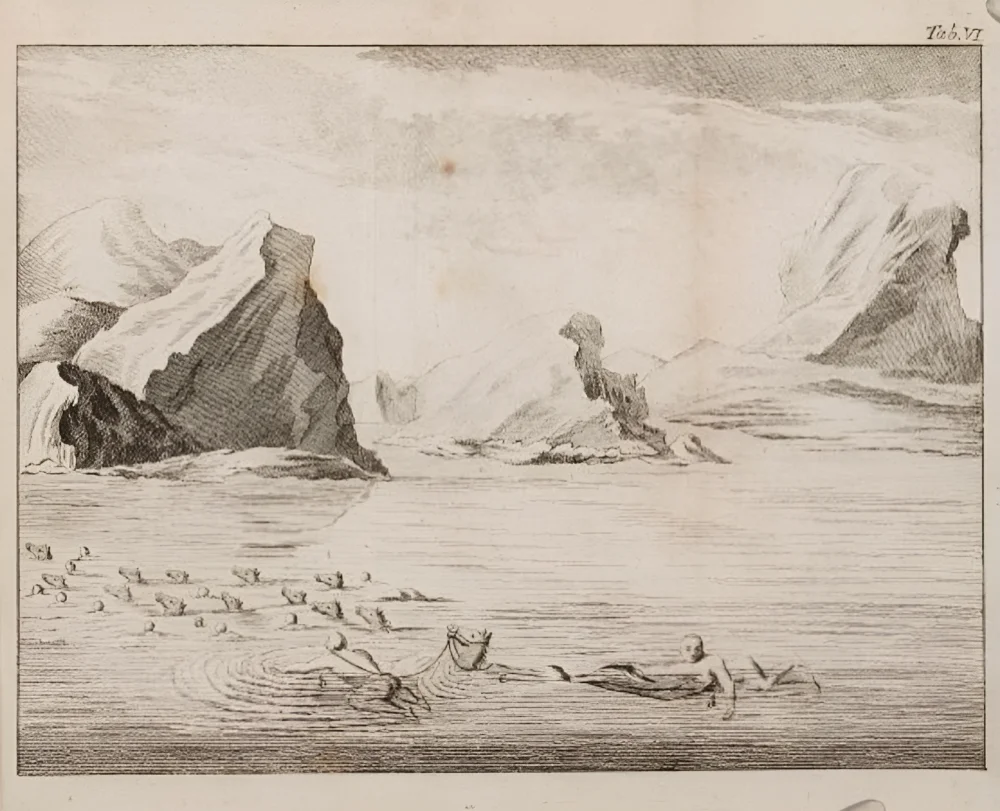

John Castle. Crossing of Castle, tied to a horse’s tail, through a lake. Illustration from the book «Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde»

When Chemodurov made it clear he was unwilling to send an envoy, Castle stepped in, offering to visit the khan at his own expense. Somehow, in his mind at least, this became a ‘mission’ in which Castle took on diplomatic pretensions. He had already softened up Eraly Sultan with gifts and an offer to paint a portrait of his father. With Eraly’s support, Chemodurov acquiesced and thus, on 14 June 1736, Castle left the fortress in the company of a young German apprentice and a Tatar servant, bound for Abulkhayir’s aul. The party consisted of the two envoys plus Asan Abuys (an envoy from Janibek Khan of the Senior jüz), as well as several others.

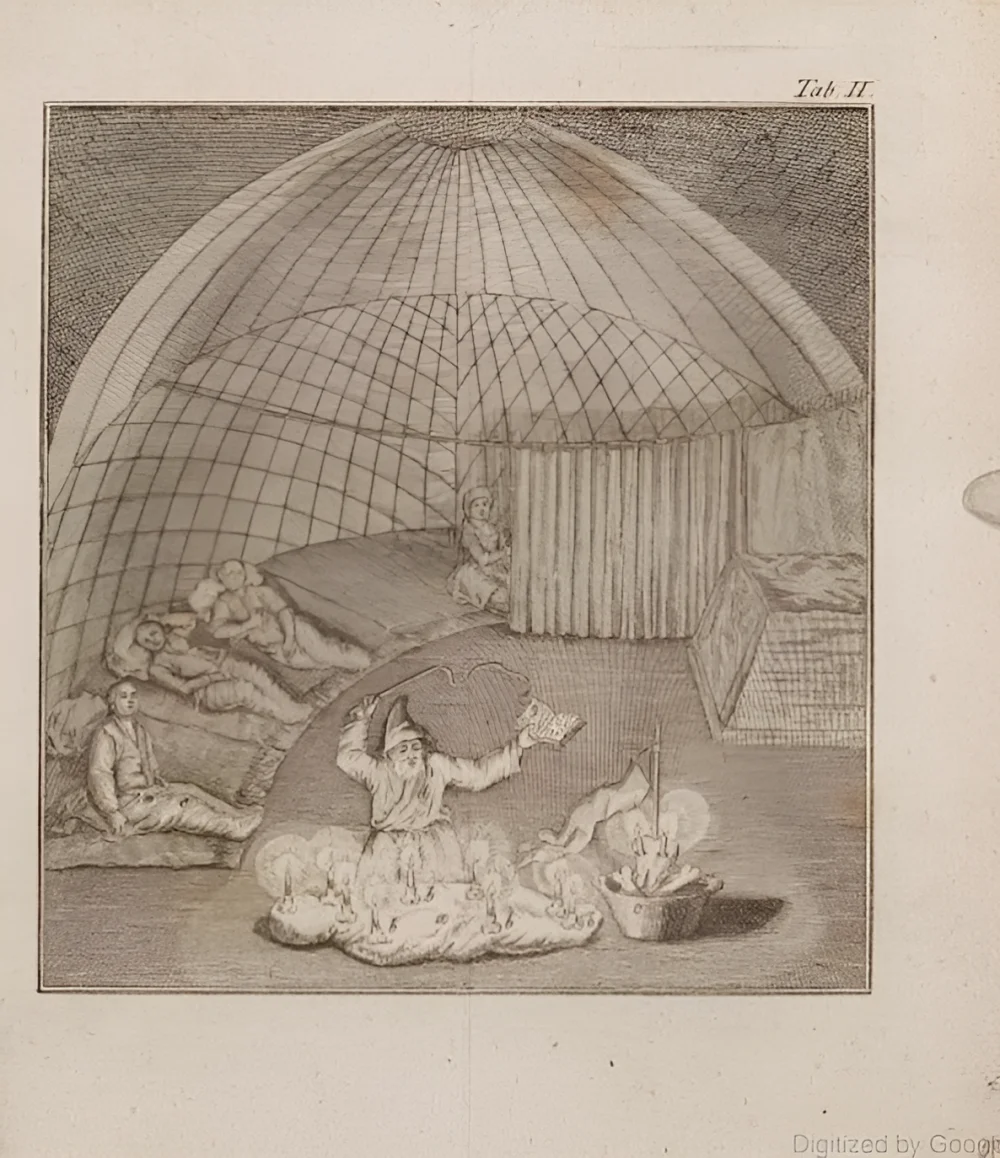

John Castle. Nighttime sorcery on the occasion of Castle’s arrival: the author with two interpreters and the yurt hosts. Illustration from the book «Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde»

After five days of travel to the southeast, they reached the aul, although the khan was not there. Nonetheless, in his words, Castle was of great interest to the Kazakhs, who inspected his clothing (especially his buttons) and baggage in detail and were particularly fascinated by his watch. His flintlock musket also attracted much attention as the Kazakhs had only previously seen more basic matchlock weapons.

That evening, after more dignitaries arrived, he was invited to dinner, where he tasted kumyssi

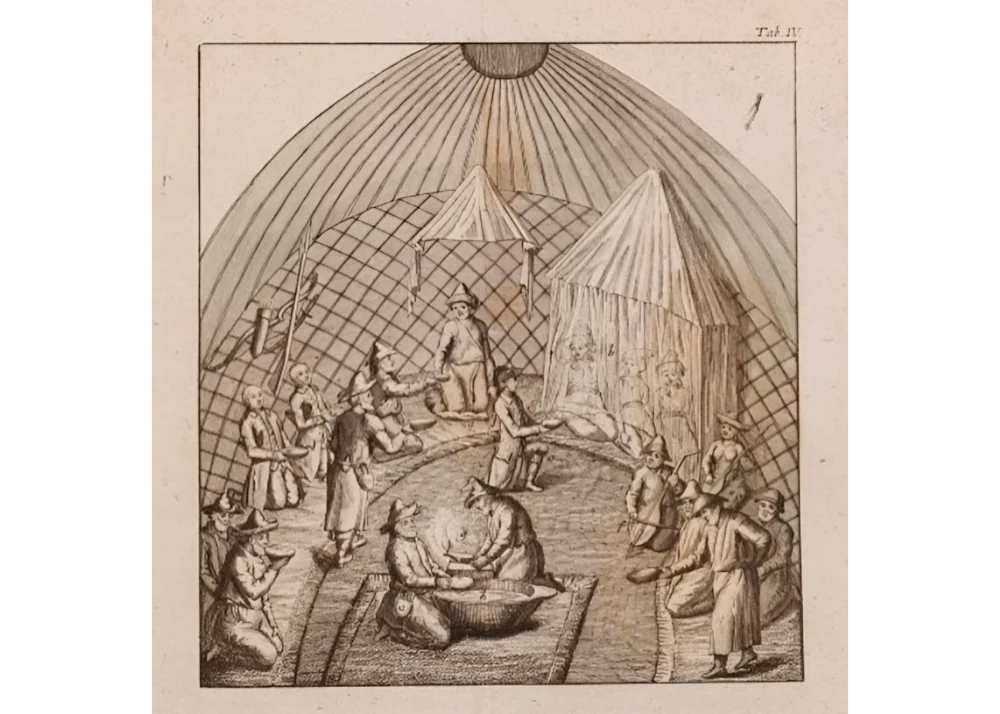

John Castle. Fortune-telling to determine whether the travelers’ chosen route was correct. Illustration from the book «Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde»

Castle rode out with three of Abulkhayir’s sons the next day, who although initially haughty, reassured him that they stood by the oaths made to the Russian empress. Finally, Abulkhayir returned to his aul on 21 June and sent a message to Castle asking him to arrive at his yurt on horseback wearing his German clothing.

The Khan and a Curious Englishman

As he entered the yurt, Castle saw the khan wearing a grand striped chapan (coat), sitting with his brother Niyaz Sultan and his two sons, along with many elders from the horde. Abulkhayir, like his envoys, wanted to know if the Russians were serious about staying in Orenburg. If so, he said he would forbid his subjects from joining an Ottoman-inspired Kalmyk uprising that was in the offing. This revelation about a possible uprising is not mentioned in any of the histories I have read and appears to be a new and interesting factor in the relationship between imperial Russia and the steppe tribes.

John Castle. Castle’s audience with Khan Abulkhair. Illustration from the book «Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde»

It ought to be noted that it was mostly the Buddhist Kalmyks who did not rise up on this occasion, not the least because they were the historic foes of the Kazakhs and other Turkic tribes. But a few decades later, in 1771, more than 200,000 of them, mainly from the east bank of the Volga, left to return to their homelands in Dzungaria, a mass exodus recorded in Thomas de Quincey’s famous essay ‘The Revolt of the Tartars’.

Whether or not there was ever a serious Ottomans attempt to foment an uprising amongst the various tribes on Russia’s southern borders is unclear. The chances of a union between Kalmyks, Kazakhs, Karakalpaks, and Bashkirs, for example, looked unlikely. They all competed over grazing lands and regularly mounted raids against each other. The Russians knew that eventually they would have to suppress the anarchy that regularly breached their borders.

A Portrait and a Mission: Diplomacy in the Steppe

Castle, who presented himself as a mediator between the khan and the empress, reassured the former about this, adding that the Russians would leave neither the Crimea or the Kuban region. Abulkhayir seemed reassured and after this, fed Castle mutton with his own hands, a distinct honor in the Kazakh tradition.

John Castle. Presumably portrait of Khan Abulkhair / Tretyakov Gallery / Wikimedia Commons

Castle’s detailed description of the diplomatic and domestic rituals in the aul of a ruling khan is probably unique and is of great value. As was noted:

Castle’s detailed portrayal of Abulkhayir’s appearance and actions enables conclusions not only about the khan’s personal attitude toward the Englishman, but also toward the Russian Empire as a whole, which the traveller representedi

The audience was over in three hours, and Castle left the yurt in the company of twenty men who, according to Castle, tried in vain to prevent the large crowd outside from touching him for good luck. It must have been a remarkable experience.

The next day, he traveled with the khan to the yurt of one of his wives, where again he was fed by hand as he listened to music. En route, Abulkhayir pointed out places where he thought Russian fortresses could be built.

John Castle. Castle’s audience with the khan’s wife, to whom he presents gifts. «Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde»

Castle was also shown how to hunt with eagles:

On the way, the Khan diverted me with the chase, which consisted of this, a bird that is even stronger than an eagle and is called pickurti

He also provides vivid descriptions of the interior of Abulkhayir’s yurt, including the clothing worn by his baibiche, his senior wife (of three), the sultana. She wore a red silk dress, richly decorated with golden flowers and a high ornament embroidered with gold on her head. The two other wives were wearing Buhara velvet and the traditional kimeshek headdress made of white cotton, capped with a large turban. Castle presented numerous gifts to the sultana, including a pastel portrait of her son, which he created using his fingers instead of a paintbrush. She was moved to tears and presented him with a bowl of kumyss to honor him.

John Castle. The khan’s wife. “Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde”

The Great Feast and Empty Plates: Customs and Misunderstandings

In the third week of his stay in Abulkhayir’s aul, on the day of the full moon, the khan held a great feast in Castle’s honour, or so he claims, with guests from all three Kazakh hordes. The feast began with Castle being seated in a separate tent, and it was only after the meal was over and most of the guests were thoroughly inebriated that he was brought into the main yurt. When he asked to be fed, his hosts told him that all the food had been finished.

‘So, on the occasion of this great feast, which had been ordered in honour of my arrival, I had to go to sleep hungry,’ he wrote in his diary—although not before he took down a list of all the eminent guests at the feast.

Castle also recalls, what seems like a rather fictitious accounting of events, that a couple of days after the feast, he was surprised when two young women entered his yurt, undressed, washed themselves, and then got into bed with him. ‘I made my excuses and said that my religion did not permit this sort of thing,’ he wrote. The following day, after a month with the Kazakhs and laden with the gifts of a horse and wolf and fox skins, he bade the khan farewell, who told him, as he recalls, that he would like to obtain a house in Orenburg and place three of his sons in government service. The size of Abulkhayir’s encampment can be estimated from Castle’s comment that for the first four to five hours after leaving the khan’s aul they rode northwest through ‘nothing but yurts’.

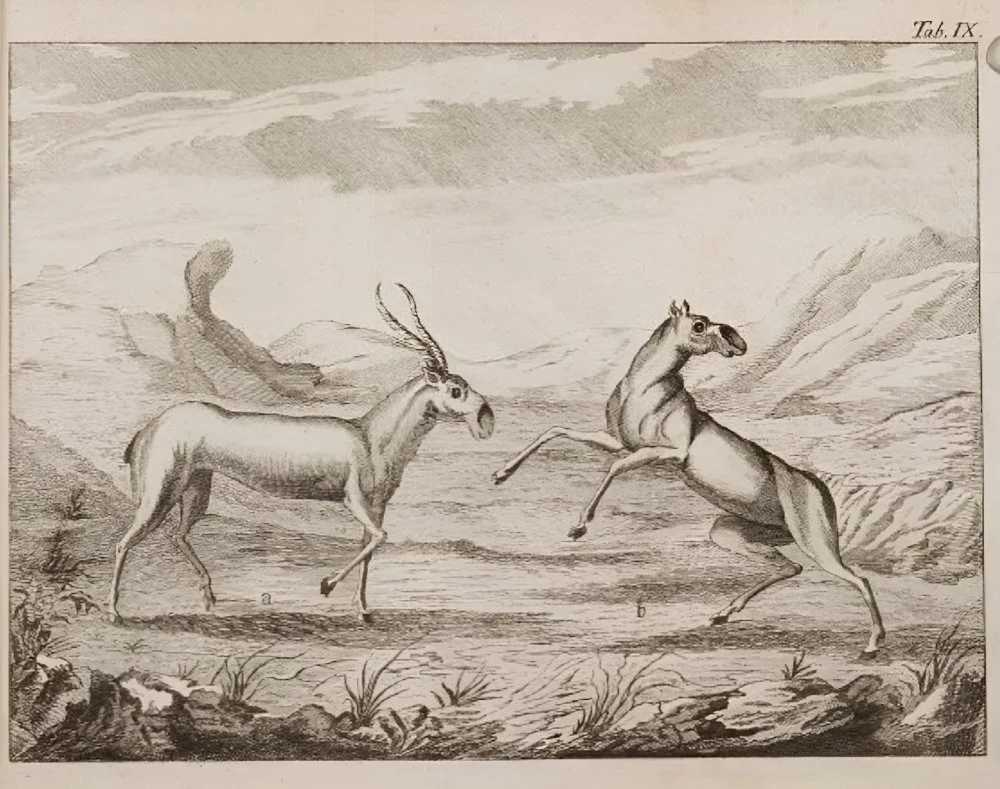

John Castle. Wild goats (probably saiga). «Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde»

The confusion over allegiances amongst both Kazakhs and Bashkirs at this point is illustrated by the fact that on this journey, Castle came across several bands of horsemen who had clearly been involved in fights against the Russians, including some who had been turned back in front of Orenburg. Castle proudly claims his intervention prevented this piecemeal revolt from becoming more general. He says he even shaved his head and put on ‘Tartar clothing’ to avoid being mistaken for a Russian.

From Honour to Humiliation: The Long Road Home

Finally, at the beginning of August and somewhere to the south of present-day Ufa in Bashkortostan, Castle met up with state councillor Ivan Kirilov, head of the Orenburg Expedition, who had been brutally suppressing the Bashkirs and building defensive forts along the Yaik and Samara rivers. He handed over his diaries and a written report to Kirilov, emphasizing how his actions had prevented an uprising and that the Middle jüz was also willing to submit to Russian control. Kirilov, who knew of Castle, seemed very pleased with him and directed him to take his Kazakh companions back toward Orenburg and the steppe.

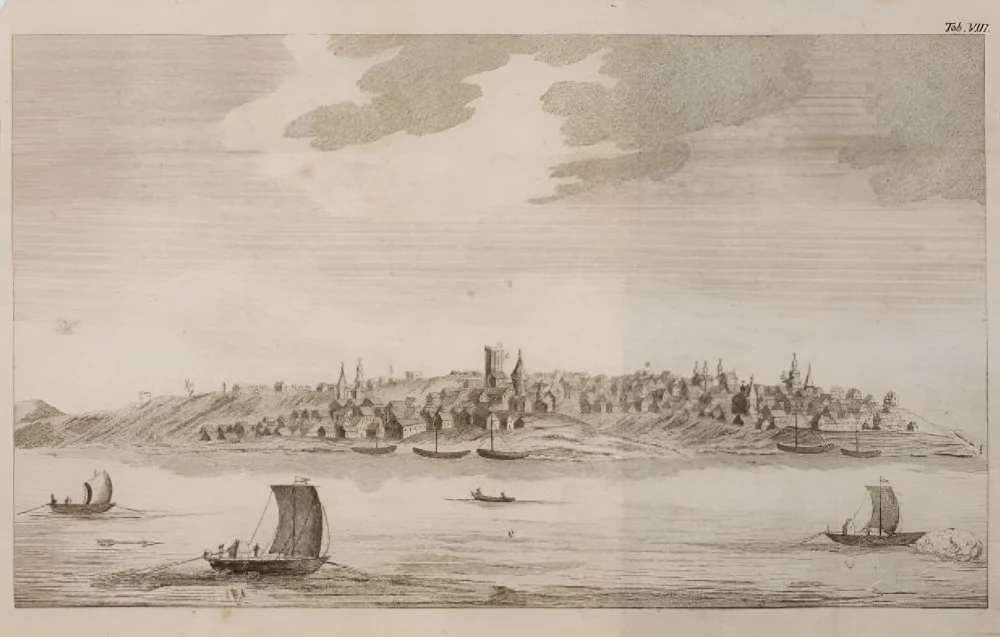

John Castle. View of Orenburg (Orsk) on the Or River. «Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde»

From Orenburg, he joined a group of soldiers floating on barges down the Yaik toward the Cossack town of Yaik (now Uralsk) and from there, he moved on to Samara on the Volga. From here, he went north and crossed the Volga to Simbirsk (now Ulyanovsk), where once again he met up with Councillor Kirilov, who had heard from his father, who believed him to be dead. At the same time, Kirilov was in no rush to allow Castle to report back in person to the empress in Saint Petersburg, or to pay him his wages. Instead, after a delay of several months, he was ordered back to Samara, with the prospect of perhaps being sent to India as an envoy. For all intents and purposes, it looked like Kirilov was trying to prevent him traveling to the Russian capital.

John Castle. Views of Samara. «Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde»

During his journey to Samara—it was now mid-March 1737—Castle’s sledge fell through the ice, and he lost almost all his possessions. Once again, having reached Samara, he was ordered back to Simbirsk, where a large group of soldiers assaulted him rather seriously on the orders of the local chief of police. He was then marched through the town to the local prison. On his release a few hours later, he found that most of his written notes, Bashkir journals, and drawings had been stolen and that he had been evicted from his lodgings. He was forced to return once again to Samara, where Privy Councillor Vasily Tatishchev took pity on him and eventually paid him what the wages he was due and granted him an honourable discharge from the expedition in June 1739.

Fact, Fiction, and Ethnography: Castle’s Enduring Legacy

The rest of Castle’s diary consists of a description of the Kazakh territories, a detailed, almost ethnographic, description of the Kazakhs themselves and notes on how they were governed and what their intentions were. It ends without providing any further details of his life, and concludes Castle’s experiences in southern Russia and the steppe.

So what then are we to make of these experiences and writings? Did his journey to Abulkhayir result in any concrete achievements? He himself claimed he had forestalled an Ottoman-inspired general insurrection by Kazakhs, Kalmyks, and Bashkirs against the Orenburg Expedition. There is little evidence to support this claim—and the Russians were already involved in a bloody conflict with the Bashkirs that resulted in the latter’s destruction as a military force. But without doubt, he gained very useful insights into what the steppe nomads were thinking.

John Castle. Kazakhs greeting. «Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde»

And yet, from the moment he returned from the steppe, Castle seems to have been treated like a pariah. His almost cavalier treatment by Councillor Kirilov, particularly the attempt to send him to India—suggests that the Russian commander did not want anyone else to take credit for the successes of the military campaign on Russia’s southern borders.

However, Castle’s ability to make connections and to be accepted by the Kazakhs he met resulted in him providing the world some of the best early ethnographic material on the steppe dwellers from any source. His detailed description of rituals, customs, and artefacts are unique. Most particularly, his drawings and paintings are superb and full of intriguing details. It is only a pity that more did not survive. We know, for example, that he completed an album of landscapes from Bashkir lands in 1735, a year before he met Abulkhayir. These, together with other works, were lost when his sledge fell through the ice.

John Castle. «Diary of a Journey in 1736 from Orenburg to Abulkhair, Khan of the Kirghiz-Kaisak Horde»

But the thirteen etchings contained in his book and the two surviving paintings, including his portrait of Abulkhayir, are stunning. The portrait, which is in the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, is now used on the stamps of Kazakhstan and is perhaps the earliest surviving portrait of a Central Asian ruler painted by a European. Castle’s reported conversations with the khan and his family and entourage are also without precedent.

John Castle might have had pretensions of grandeur, but his audacity in confronting a ruler in the steppe, who was unsure about accepting Russian control, is unquestionable. Even after many setbacks and horrendous treatment by Russian officers, Castle never lost sight of what he considered to be his ‘mission’ to the steppes. Even today, his sense of determined duty shines out from his writings. Whatever his personal motives were, and no matter how long we had to wait to get his works in a readable form, it was more than worth the wait.